Reznicek, a fabulous, new Viennese restaurant by sommelier Simon Schubert

I’m writing this month’s newsletter in Vienna even though I thought about canceling this trip, as I have frequently done in the last few months due to Covid and the war next door, but I figure I can’t wait forever for the world to stabilize in every direction to feel completely comfortable traveling in this area. My wife and I decided to take a few days in Austria and the Czech Republic for her birthday before the arrival of some of my team from the States. This week is the beginning of forty consecutive days I’ll be on the road, starting in Riesling and Grüner Veltliner country, ten days in Northern Italy between Südtirol, Lombardia, and Piemonte, followed by what will surely be a stunning train ride from Milan through Switzerland and into Germany. From there, after a brief German excursion with Katharina Wechsler, the first team goes home, and I fly to Madrid to welcome three others for two weeks in Iberia. It’s going to be an intense one, but it will clear my schedule for a more relaxed summer.

Last night we went to one of Vienna’s cool wine spots, Heunisch & Erben. It had been an overcast day, a little chilly but sunny, similar to when we left Portugal, though a bit drier. We settled into a tastefully remodeled modern flat with a light oak and shiny dark marble floor apartment with the classically high ceilings in a historic building in the Neubau district of Vienna. The original plan in Austria this year was to go to VieVinum, but despite how great the event is, I opted to avoid the crowds and see our Austrian growers in a more intimate setting.

Ever since my first visit in 2004, I’ve searched Austria for the best wiener schnitzel and I may have finally found it. Two nights ago, at Heunisch & Erben, Katharina, our server, gave it a 9.5 out of ten, and I had to agree, only because she insisted a ten isn’t possible. It was near perfection: thin, soft veal somehow floating inside and seeming not touching its pillow of gold and brass-hued breaded crust with a superb and perfectly crafted delicate crunch. Their wine list is massive and requires a thirty-minute hunt to settle on the bottle for the night. We scoured the list of old Riesling with one of the sommeliers but he didn’t commit to pushing us in any particular direction, so we started with a series of Riesling tastes from their extensive wine-by-the-glass list and asked for a bottle of 2017 Domaine du Collier Saumur Rouge “La Ripaille” (because we knew we wanted a red for the night as well) to nurse over the next hours. During the last two years, I’ve had three different bottles of this Collier wine, two 2014s and one 2016. The La Ripaille Cabernet Franc wines I’ve had are, to me, complete in every way, and loaded with x-factor and perfect texture and palate weight. The 2017 clearly needs a few more years for the newish wood notes (not sure of the wood regimen) to meld a little further into the wine to make it a true 9.5. It was a solid 9, but I’m sure it will go up a notch with more bottle age.

Everyone who will join me on this five-week journey will experience new places and meet new people that they admire through their wines. It’s a great pleasure to watch them visit places for the first time that I’ve had the fortune of visiting many times before, thanks to the great support of our customers and friends in the wine industry! Sometimes during the first visit to anywhere we are so worried about avoiding missteps that further complicate our travels that we miss the pleasure of watching others enjoy themselves too.

My fondest memory guiding someone to somewhere I frequently visit was with my sister, Victoria (also our company’s Office Manager and Company MVP—yes, the second should be an official title), the first time she went to the Amalfi Coast. My wife, Andrea, and I lived on the eastern border of the area, in the port town of Salerno, a place people often just pass through without staying for more than a day or to just hop on the bus to Amalfi; Salerno is a true Southern Italian city populated mostly with Italians. Almost every sunny weekend we would catch the ferry to one of the Amalfi Coast villages, and our favorite was Cetara.

Amalfi Coast fishing village, Cetara

On the ferry ride we sat daydreaming while sea mist cast into the air by the boat bobbing up and down in the wake from other boats, the cool water freshening our faces under the hot sun. But anyone familiar with the area knows the better beaches, at least for relaxing, are to the east and south of Salerno in Cilento, not the pebbly and cobbly Amalfi Coast. The Cilento Coast is much flatter and has expansive and long, soft beaches made of fine sand, save the occasional razor-sharp volcanic outcroppings on the shore and scattered in the breaking waves. The water is cleaner and clearer than most of Amalfi (a place already known for its beautiful, clean water), and it’s where many Campanians go during the summer when excessive amounts of tourists make Amalfi unbearable, if it weren’t for its breathtaking beauty. One can only imagine the origins of the beauty of the Amalfi coastline adorned with limestone cliffs: surely it was the hot spot for torrid love affairs between gods. In Cilento, every beach shack restaurant surely has better food than you can find anywhere else on the beach in Europe; the Neapolitans have very high expectations when it comes to food and these places deliver, even if they’re served on paper or plastic.

The place was Ravello, perhaps the most picturesque and well-kept village along the Amalfi Coast, a hilltop town about a thousand feet above the sea, celebrated in books, clean and well-groomed, and subtly posh. It’s a place that attracts the richest and the most artistic of our species for inspiration from the Mediterranean below, with its shimmering kaleidoscope of inimitable shades of blue and green, all backed by a treacherously steep, wild shrub-covered, limestone mountainside that seems to run right into the city center. It was only there that I ever witnessed someone so deeply awed by the beauty of a place that it brought them to tears. This person was Victoria, who was embarrassed by how it moved her, and this is, and will always be, one of my greatest travel memories.

There won’t be anything quite as stunning as Ravello and the Amalfi Coast during my upcoming trip, but Galicia’s Ribeira Sacra and Portugal’s Douro will stimulate many other sensations: vertigo; disbelief that people would elect to work in such extreme conditions; deep contemplation about the history of conquest and religion in the region; the superiority of Roman engineering in their time and their lust for gold and how deeply they changed Europe. All this lies between our start in Austria’s Wachau and our terminus in Portugal and Spain’s Atlantic coasts. So much to see and experience, to learn and to ponder! It never gets old, only we do…

Ancient gneiss from hundreds of millions of years ago, the famous bedrock (or “primary rock”) of Austria’s Wachau

New Arrivals: Austria

Tegernseerhof, Wachau

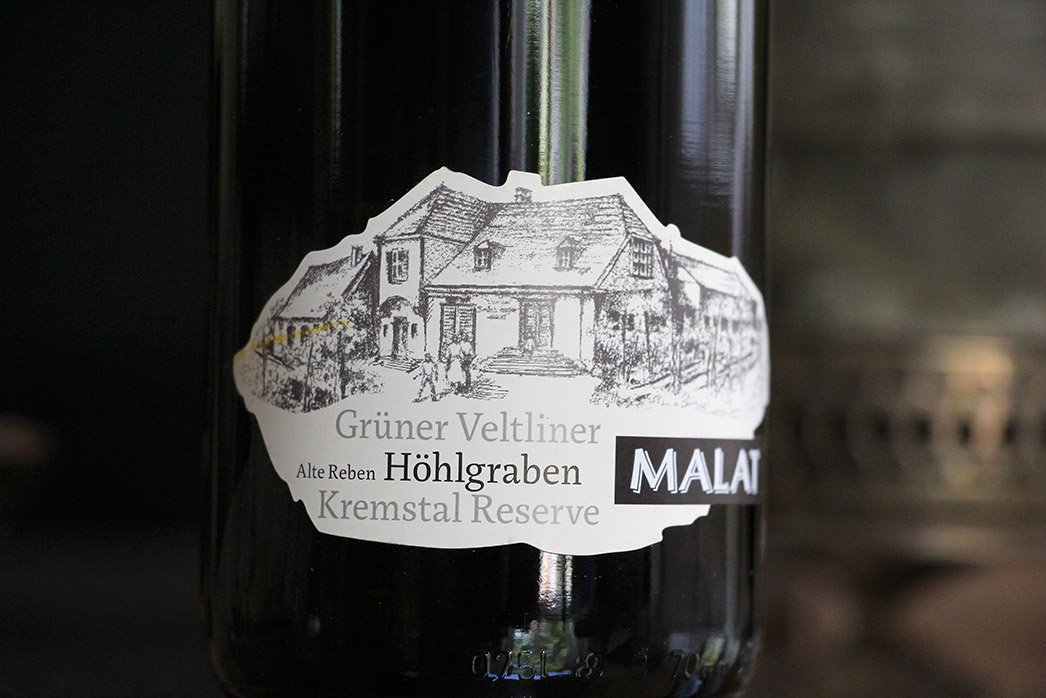

An hour’s drive west from Vienna lies Austria’s ground zero for the country’s great Grüner Veltliner and Riesling. While I feel it’s not fair to say one region is better than another when comparing Kremstal, Kamptal, and Wachau, Austria’s elite spots for these grapes, Wachau certainly gets heaped with the most praise and is home to a tremendous number of great producers, including our friend Martin Mittelbach and his historic Weingut Tegernseerhof.

The far eastern side of this appellation’s steeply terraced, ancient gneiss rock hillsides is where the recently organic certified Tegernseerhof has operated since 1176. While vines existed in the area for hundreds of years before the arrival of the monastic order of Tegernsee, Tegernseerhof is the oldest Wachau winery in the Loiben area. Owned and operated by the Mittelbach family for the last five generations, there are dozens of winegrowers in the area now, including two of Mittelbach’s neighbors and close family friends, the Knolls and Alzingers. Martin’s stylistic difference from his friends lies mainly in how he now organically farms and is certified (and I could see that would eventually head that direction when I first met him in 2009) and uses only stainless steel for fermentation and aging. He is also slightly stricter about excluding berries that are concentrated by good botrytis in his classic still wines from Grüner Veltliner and Riesling. Similar to the others, however, skin contact is used depending on the health of the berries: the better the health and the greener the berries, the longer the maceration before pressing. His vineyard and cellar choices leave Martin’s wines naked with a starkly clear view into the differences between the aspects, slopes, bedrock and topsoil, and genetic material from each particular vineyard site of his top wines. Always straight and intentionally slow to unfold upon opening, Martin wants his wines to evolve through time rather than erupt in the first moments. To better understand terroir with an extremely fair-priced wine, Tegernseerhof is second to none—make sure you do more than just taste them; better to drink them over some hours next to each other to let the differences truly reveal themselves.

What a treat to have more 2019 vintage wines coming from Austria. Similar in overall caliber to other recent banner years, 2017, 2015 and 2013, 2019 may be considered a leader among them. Of course, each vintage has its standout characteristics, but 2019 fires on all fronts, leaving nothing ambiguous regarding its potential as well as its natural openness early on. The ripeness is full but balanced with zippy acidity and mineral nuances and loads of texture. It’s a great vintage on which to double down: one for today and another for the cellar.

The Austrians are crazy about Grüner Veltliner. Why, one might ask? It’s extremely universal. It invites everyone with its mixed simplicity and convivial nature, and with the good ones, a deep but unintrusive complexity. At home, grandma, grandpa, mom and dad, and the entire extended family, and some of the country’s older kids enjoy their time together with this appealing white wine shared among everyone. Yes, Austrian teenagers drink wine (and probably more beer) with the family and in restaurants. The public drinking age in Austria is 16, and alcoholism is not a big societal problem thanks to the lack of taboo… Better to get them started on Grüner Veltliner than waste the Rieslings on them at such a young age! (Save the Riesling for the adults!) Interestingly, when asked which wine between Grüner Veltliner and Riesling may age better and even improve more, many of the winegrowers have a strong belief that Grüner Veltliner may slightly outdo Riesling in the long run. And if anybody knows, they would!

Grüner Veltliner is a grape variety that doesn’t like to suffer too much stress in the vineyard, that is, benefit from the vine’s search for nutrients and water in the soil. It’s mostly planted on less extreme slopes and on deep soils, whereas Riesling takes to more precarious, spare soil, with picturesque positions that result in greater stress to the vine. Here in the Wachau and the surrounding regions, Veltliner loves to bathe in the water-retentive loess, a wind-traveled, fine-grained, and well-structured calcareous sand—well structured enough through its crystalline matrix that entire loess caves can be dug relatively deep into the earth with very little structural support and concern of collapse. Most of these loess vineyards in the Wachau are down by the river, on more east-facing terraces or in areas inside the river’s historical flood plains.

The first Grüner Veltliner and Riesling in Tegernseerhof’s range are labeled Dürnstein (formerly labeled Frauenweingarten for the Veltliner, and Terrassen for the Riesling). The Dürnstein Grüner Veltliner Federspiel is grown on alluvial river sands and loess which brings bright notes of spice, honeysuckle, and white pepper to the forefront and a broader palate richness. (Federspiel is a ripeness category particular to Austria’s Wachau region, similar to a Riesling Kabinett in ripeness level but a dry wine rather than a sweet version one would typically expect with the reference to Kabinett on the label.) The mineral nose is further enhanced by notes of dried yellow and green grasses, and white radish, while the deep and glycerol back palate is characterized by Indian spices and a slight minty, lime finish. Between the Veltliners in Tegernseerhof’s range, this is the easiest and most universal for all palates.

Grown in a parcel only a few dozen meters from the Danube and right at the doorsteps of the historic rock village, Dürnstein, Tegernseerhof’s Superin Grüner Veltliner Federspiel is quite different from the Dürnstein bottling. Here the Danube did some sculpting and stripping away of soil during flood periods while replacing it with new river sediments. Through this erosional process, it carved deep enough to expose the gneiss bedrock below. In other Grüner Veltliner vineyards used for Federspiel, they are often covered in a deep enough topsoil of loess and alluvial sediments with very little, if any root contact with gneiss bedrock far below. The dynamic of gneiss as a dominant feature of this vineyard creates a Federspiel Grüner Veltliner with a much more vertical, mineral, saltier, and deeply textured palate. Between the two Veltliners, this is the one for the mineral seeker while the other may be better suited for those in search of more obvious Veltliner deliciousness.

The three newly released 2019 Tegernseerhof Grüner Veltliner Smaragd Crus are all located in the Loiben area. Leading with the most elegant of the three, we start with Loibenberg, a Smaragd (the Wachau’s regional name for the highest quality dry wines; think the equivalent of a dry Spätlese or Auslese-level trocken) grown on numerous parcels on perhaps the most recognizable hill in the Wachau. Unlike many other Grüner Veltliners from this hillside, similar to other Loibenberg Grüner Veltliners, Martin’s is a mix of around 2/3 loess-dominated soil in the middle and lower parts of the hill, but with the other third harvested from gneiss-dominated soils and bedrock further uphill, which may make (in theory!) his version a little more minerally than one may expect from a Smaragd Veltliner from this hill. The aromas and flavors express a beautiful collection of sweet purple fruits, Concord grape skin, violets, green melon, green candy, Meyer lemon, and kaffir lime. Tucked further in this tension-filled but open Veltliner sits a deeply rooted core of iodine, sea urchin, and marine salts.

One of the most famous and exclusive vineyards in the Wachau is Ried Schütt. As far as I know, only Weingut Knoll and Tegernseerhof have labels that carry this name; both have Grüner Veltliner, but Knoll is the only one to bottle Riesling, which some say is the best Riesling in Knoll’s impressive range. This Veltliner from Mittelbach is slightly more textured and amare (in a very pleasant way!) than his Loibenberg Grüner Veltliner, with ethereal aromas of fresh sage, spice, exotic greens, and sweet lemon. On the palate, the aromatic sweetness of bay leaf stains deeply on all sides, while sweet green grasses, marine salt, and lightly purple and yellow citrus fruits round out the full but clean palate. Schütt is perhaps the most regal and firmly textured of the Veltliners from Martin, and it sits beneath Höhereck inside of a combe (known as the Mental Gorge, or Mentalgraben) where water eroded the eastern neighboring hillside of the Loibenberg vineyard just across the way. The combe floods with cold air from the Waldviertel forest behind and above the vineyards, contributing tension to balance out its deep power. An unusual look for a great cru site, it’s a relatively flat vineyard with only slight terracing below Höhereck. It’s composed primarily of hard orthogneiss bedrock and decomposed gneiss topsoil with a mixture of different sized, unsorted gneiss rocks and sand deposited by the former water flow.

Replanted in 1951, Tegernseerhof’s Ried Höhereck is the Grüner Veltliner parentage of many vines in the area. A rare Grüner Veltliner planted almost exclusively on the acidic metamorphic rock, gneiss, rather than the sandy, nutrient-rich and water-retentive loess, typical for this variety with a beneficial southeast exposure inside and just popping out of a ravine with great access to mountain winds and an early summer and autumn sunset, Martin says that the most important element of Höhereck is its genetic heritage. This half-hectare (1.25 acre) vineyard has been a growing field for centuries for ancient Grüner Veltliner biotypes, thus contributing to the complexity of this wine and Martin’s entire range of Veltliners, with all new plantations made with genetic material from this hill. Höhereck produces dynamic wines that still manage to show great restraint, though this is perhaps due to its great abundance of layers that unfold once the bottle is open; it shouldn’t be drunk quickly because all the most important acts of the show take time. As charming as it is serious juice, with precise nuances of yellow and white peach, cherimoya, lemon curd, baking spice, bright green herbs eventually take center stage. It’s a lovely wine with immense depth.

We have a rock star lineup (pun intended) of 2019 Tegernseerhof Rieslings grown on gneiss bedrock with slight variations of exposure and topsoil. First, we start with Martin’s rapier-like Dürnstein Riesling Federspiel (formerly labeled Terrassen). Every year this Riesling shows a gorgeous selection of green notes that dance somewhere between sweet mint, green fig, green apple skin, and sweet green melon, with razor-sharp steel and crystalline, salty mineral notes adding to its appeal. These grapes come exclusively from the first and second pickings of Riesling clusters from the gneiss terraces of some of the region’s greatest badass Riesling vineyards: Loibenberg, Steinertal and Kellerberg. The pedigree is all there, and Martin’s deft touch and desire to craft this wine into fine liquid art, making it one of the world’s greatest values for serious but delicious white wine.

In the range of Martin’s Smaragd Rieslings, the Loibenberg Riesling Smaragd is the most delicate and refreshing while maintaining its Smaragd-level fullness. It comes from one of the warmest sites in the Wachau (which is still much cooler than most parts of Austria’s white wine regions) and is often the first to be picked within Tegernseerhof’s Smaragd Rieslings. The numerous parcels that are scattered over this large hill give the wine a great balance of characteristics from sweet Meyer lemon notes to the first pick of yellow stone fruits in early summer. It has a wonderfully refreshing spring-like feel, adorned with sweet flowers, acacia honey and early spring grasses. Indeed, spring and summer nuance is what this wine is all about, however, earthiness and forest floor notes are very present. As already noted, Martin prides himself on the savory and subtle nature of his wines, all framed with precise and regal mineral notes of river rock and freshly scratched metal, like a carbon steel knife after a good scrubbing. Refreshingly delicate for a Smaragd, it’s one of the most quaffable in the range and can be thoroughly enjoyed without the need for your full attention on each sip.

If there is one wine in Martin’s range that he (and I!) might favor, the Steinertal Riesling Smaragd may be it. This tiny vineyard’s particularities give its wines tremendous range and also make it uniquely special. Steinertal is one of the great sites in all of Austria and its aromas beam from the glass with enticing and full-of-energy, high-toned mineral impressions; if it sounds exciting, that’s because it is! These elements of the wine are likely due to its growth in purely gneiss rock, spare topsoil and Martin’s preference for earlier picking and rigorous sorting to remove any concentrated botrytis grapes. The vineyard’s heat-trapping amphitheater shape and the steep ravines on both sides also create a teeter-totter of hot days and the cold nocturnal mountain air that breezes in and cools down the vineyards. My tasting notes from last summer express that the second glass emits discrete, late summer stone fruits, citrus, flowers, and French lavender. Exotic and sweet herbal notes follow, displaying fresh thyme, lemongrass and subtle wheatgrass and watermelon rind nuances. In the deepest parts of the wine, the acidity is fluid but intensely focused, supported by a gentle gust of palate-refreshing tannins. This full-scale orchestra of profound intellectual and hedonistic pleasure seems endless, so prepare yourself. If one were to cut their Wachau teeth on this Riesling, it may set the bar a little high. As Burgundy grower David Duband says when we dig into his grand crus at the cellar, “Be careful. It’s very good…”

If one were to ask a knowledgeable wine professional about the greatest vineyards in Austria, the Wachau’s Kellerberg would likely be mentioned in their first breath. Keller-berg, or “Cellar-mountain,” is without a doubt one of the Wachau's greatest vineyards, and Tegernseerhof’s Kellerberg Riesling Smaragd is the fullest Riesling in their range, surely vying for the top spot with Steinertal. Imposing and profound in every dimension (very Chambertin-like in this way), from structural elements to the balance of power and subtlety, the only known weakness of this type of wine can be its maker; fortunately, Martin has a handle on it. To attempt to describe all the nuances of this wine would be a paragraph with no end. However, to better understand the wine’s nature it would be easier to demonstrate it with an explanation of its terroir. The hill faces mostly southeast, giving it good morning sun but also an earlier sunset than the neighboring Riesling vineyards with more southerly and sometimes western exposures, like Loibenberg and Steinertal. Similar to Steinertal, Höhereck and Schütt, and unlike the main face of the large Loibenberg slope, Kellerberg is exposed to a large, open ravine to the east that brings in a rush of cool air during the night. The aspect and exposure to this ravine, along with mostly unplanted hills just to the west, allows the fruit to mature to ripeness without imparting excessive fruitiness, while highlighting its pedigreed gneiss bedrock and spare topsoil. It has a deep range of topsoil from volcanic, loess and bedrock-derived gneiss, and Tegernseerhof has six parcels inside its boundary that cover these soil types. Loess brings richness and lift, gneiss the tension and focus. Even more important than the nuances is the way this wine makes you feel: the energy, the profound reservation, and at the same time its generosity. Kellerberg is formidable and does indeed comfortably sit among the world’s greatest vineyards.

There are also reloads of Tegernseerhof’s popular 2019 Bergdistel Grüner Veltliner und Riesling Smaragds. These wines labeled with the name Bergdistel are a blend of many different small plots not big enough to be made into their own wines. Some of the grapes also come from further west of Dürnstein, closer to Weissenkirchen, home to many great vineyards, most notably (for me) Achleiten. Tegernseerhof’s renditions of these wines are his most generous in the Smaragd category. They are another great example of drink-it-don’t-think-it fabulous Smaragd Rieslings that don’t hold anything back immediately upon opening.

New Arrivals: Italy

Poderi Colla, Piemonte (Langhe)

I think I write more about Poderi Colla in our newsletters than any other producer we work with outside of Arnaud Lambert. We always have new things coming from these guys and they’re fun to talk about. The Collas, like Lambert, are one of the most important cornerstones of our entire portfolio. I simply never tire of drinking their wines and would be happy to have them as my desert island red wine producer, although the island would have to be a little less tropical because warm Nebbiolo doesn’t sound so appealing… The reason for my infatuation—that could more aptly be described as absolute love—is simple, but also a little complicated to explain… Colla is among very few other producers throughout Europe who represent to me an unmovable historical wine culture.

The Collas, like other quiet giants of the wine world, didn’t alter their course over the last fifty years regardless of the constantly changing wine styles the broader market wanted. Through the years of conformity in the global market in European staple regions like Tuscany, Piedmont, Rioja, Burgundy and Bordeaux, some producers stayed the course on more natural methods through the age of chemical farming (since WW II), the caricature-like muscular and overplayed wines of the Age of Extraction (1990s-2000s), until today, with the welcome movement away from those eras toward softer handling and elegance over power on one side, and on the other to the culture of unapologetic and, unfortunately sometimes, unaccountably flawed natural wines whose fans fashion them as a sort of punk rock-like movement; the difference is that the respectable punk rockers were good musicians that knew how to play their instruments in order to hit the notes they intended to hit. Intention has everything to do with any great wine too, “natural” or traditionally crafted.

Tino Colla in Bussia Dardi le Rose

The game-changers of old, the unflappable ones, refused to conform. Think of the many iconic and unmistakable historical styles found in the wines made by producers similar to Clape, Rayas, Rousseau, Leroy, DRC, Lafarge, Pierre Morey, López de Heredia, Vega Sicilia, Giuseppe Rinaldi, or Bartolo Mascarello; you get the point! (Perhaps the only shift in some of these producer’s philosophies in the last fifty years is in the direction of more natural farming.) For me, Poderi Colla is also on that list. It’s true that the Colla family’s wines weren’t popular for decades, but why? Because they made them like they were made in the 1950s and 60s, and they weren’t cutting edge anymore after the 1970s until about a decade ago. The Collas made their wines more or less the same seventy years ago as they do today. For example, Colla’s Barolo Bussia Dardi le Rose still goes through a two-week natural fermentation and is then aged two years in massive old barrels (50++ hectoliters) before bottling, as it was half a century ago. The difference is that now people get them because their graceful but traditionally sculpted and gently structured style is in again. Their wines are elegant and old-school, pale in color, subtle but fully expanding by the minute as they aerate, and, today, more pristinely crafted than in the past—perhaps the only thing I can think of that one might criticize about their style…

Many of the great producers of wine know perfectly how to measure the risk in walking the line of volatile acidity in pursuit of x-factor perfection while remaining only a shade to the right of vulgarity. The Collas don’t walk that line, they keep it straighter from the start all the way to the finish, and that’s one of the many reasons why their wines are so incomparably reliable in this area. In fact, I cannot think of another producer with better consistency in their entire region—believe me, I’ve tried. The Collas are indeed pure on craft, thanks to the laser-sharp attention to detail of the family winemaker, Pietro Colla, with the help of his father, Tino, and their deeply ingrained three hundred years of knowledge passed down from the many Colla winegrowing generations.

Another element I believe defines the Colla style is their unique position that lands between Piemontese and French style, more specifically, that of Burgundy and yesteryear’s Northern Rhône. I’ve often thought that the Colla’s wines would be less understood inside of a largely Italian portfolio, or a broad tasting of Italian wines because they are so straight. In many ways they fit perfectly into the expectation for the region, but in other ways they don’t. To better understand this, let’s rewind the clock a little.

Back in the early 1960s, the late Beppe Colla (the family’s spiritual leader and a quiet revolutionary during his seventy years making wine and influencing his neighbors) went to Burgundy and it changed him. He returned home and decided to bottle, with the epic 1961 vintage, the first commercially marketed single-cru Barolo, Barbaresco, Nebbiolo d’Alba, Dolcetto and Barbera. It’s hard to believe, but Beppe is the true O.G. of the single-cru wine movement in the Langhe. Beppe was the first to commercially do this in the region’s history, all bottled under the Prunotto label, a winery they owned until the early 1990s before they sold to Antinori and then launched Poderi Colla. Colla’s wines today bear the mark of that pivotal moment in Beppe’s perspective, and that’s why I view them as wines that agree as much with a French palate as with an Italian one. I’m also inclined to mention (and not massively expand on, though I really want to) that Piemonte is historically linked to France by way of the rulership of the territory by the Savoy for almost five-hundred years. Many things in Piemonte are very close to France, but none more than the Piemontese dialect, which is clearly heavy on French-like vocabulary. For me, Colla’s wines somehow embody this (even if the Collas may not see it that way), and it’s interesting to be mindful of this when their wines are in your glass. They’re surely Italian, but there is a distinctive dash of French there from influence hundreds of years ago, but even more recently with Beppe’s pilgrimage to Burgundy a half century ago.

The best news with Colla is that we have a great relationship with them, and despite their major surge of interest by the global market as of late, we are still able to import a good quantity of wine from them. Most of what we have arriving from Colla are restocks on wines that we simply can’t seem to keep around long. However, their 2020 Dolcetto d’Abla “Pian Balbo” is a new release. Dolcetto is a grape that deserves more respect than it gets. I am sure every visit I’ve had with Tino Colla he tells me that Dolcetto is the wine the local winegrowers drink the most. It seems like they would drink their top Barolos and Barbarescos with every meal, but their reality is that they focus on wine all day and at the end of the day they want something a little easier going, and less serious but also delicious and complex, and unmistakably Piemontese—and that’s Dolcetto! Pian Balbo, sourced from Cascina Drago, their magnificent vineyard on the border of Barbaresco at around 330m altitude, is macerated on the skins for a week, or slightly less, and aged in stainless steel to preserve its fresh and bright fruit profile. The acidity is cleansing and the tannins smooth and lightly chalky. It may seem strange, but I often open Dolcetto on the nights when I need a couple-hour vacation from too much seriousness in my wines, much like the vignaioli do. Sometimes I find its simplicity just as thrilling as the complexity of other greater wines. But no matter whether a wine takes itself too seriously or not, Colla’s Dolcetto, with its unmistakable Piemontese aromas and tastes, transports me back to Piemonte, and what can be better than that? And the price? At four or five bucks per glass at your home wine bar, it’s almost free.

When Dolcetto is in the right setting, however, it can indeed be serious business. We squeezed the Collas for a last batch of their 85% Dolcetto, 15% Nebbiolo blend, 2016 Bricco Del Drago, a monumental wine with this historical blend long before the concept of IGT came around, with the quality and guts to outlast even the most prestigious of Barolo and Barbaresco wines. I know that’s a big statement, but I, a former skeptic too, have been convinced of this wine’s chops from the numerous examples with decades of age, especially the 1970 that Tino Colla regularly speaks about with seemingly greater reverence than even all the great Barolo and Barbaresco he’s had in his seventy-plus years. Piedmont wine junkies, like us at The Source, know that 2016 has all the accolades (well-deserved), and they are a treasure to keep but also show fabulously now. Don’t miss an opportunity for a serious cellar wine at a very fair price for the pedigree that will likely outlive you but give you a lot of pleasure along the way. Do all those six-year-olds in your family (and extended family) a favor and lay some down until it’s time to give them some as a special and thoughtful gift. The 2016, and all the other vintages of this wine, will likely stand the test of time without much effort—probably better than many of the Barolo and Barbaresco wines from the same year, but at a third or quarter of the price.

There’s more 2019 Barbera d’Alba “Costa Bruna” arriving as well. There was a battle between our sales team for quantities of this wine for our top restaurants and I’m sure these will go fast again. Notes from November 2021 Newsletter: Almost every vintage in the last twenty-five years (save a few, like 2002 and 2014) has brought greater credibility to Barbera as a world-class variety, and 2019 has kicked it up a couple notches. The 2019 Vintage was a long growing season with steady weather all the way through, and despite the lack of extremely high temperatures in the previous two vintages, it ripened perfectly, and its naturally high acidity relaxed just enough to bring its stockpile of complexities into balance in this slow growing season. What’s more is that Colla’s Barbera d’Alba “Costa Bruna” is sourced entirely from the Barbaresco cru, Roncaglie, on what would typically be a Nebbiolo exposition facing south, and with very old vines that were mostly planted in the 1930s. It offers a diverse combination of fruits, from bright red to dark, with sweet red and purple flowers and spice. It’s absolutely another Colla wine to pepper into your annual wine schedule.

More of the outstanding 2019 Nebbiolo d’Alba hit too. We went as long on quantities as the Collas would let us with this wine. It’s truly one of the greatest Nebbiolo years and this one will simply blow out your expectations with respect to category and price. It’s made with the same care as a Barbaresco (a year in large, old botte) and has the same basic calcareous marls and sand. The difference is that it sits between 330-370m and covers a multitude of aspects from east to west, and sits at the top of the hill, fully exposed to cold air which makes for a wine of great tension and never any hint of desiccated fruit, only fresh and bright notes, like those old-school Barbaresco and Barolo wines we all miss. As we said back in our Notes from November 2021 Newsletter: While discussing the 2016 vintage in Piemonte at the start of the pandemic in Italy during a visit to the Collas (among about a dozen other top estates visits in Barolo and Barbaresco) in February of 2019, Tino Colla, who has seen more than fifty harvests as an adult, basically skipped over 2016 and jumped right into the merits of 2019, a vintage he felt would be one of the most important of his lifetime. Colla’s Nebbiolo d’Alba is a preview of that oncoming quality, and it’s gorgeous. If Nebbiolo is one of your passions and you need a price break without sacrificing quality, go deep on 2019 entry-level Nebbiolos.

For the very serious collectors and Nebb-heads, the 2017 Barolo Bussia Dardi le Rose MAGNUMS came in on this boat. The critics are circling back on this year and retracting a few of their initial concerns. Built to age for decades, and even longer in magnum, this could be a good one to take a look at. (We also have a few 2015 Barolo mags left in our inventory if mags of epic wine are your thing…)

Crotin, Asti

It seems that when we bring in wines from Colla we also take more wines from the Russo brothers at Crotin at the same time. The word Crotin is Piemontese dialect for “small cellars under the main wine cellar,” and is used for keeping the best wines for long-term aging. The Russo boys have been churning out some of the top values in Asti now for nearly a decade, under the assistance of the well-known prodigy enologist, Cristiano Garella. Their organically farmed vineyards are in some of the coldest growing sections of southern Piemonte, where the frigid temperatures offer grapes a long growing season, ideal for the high-toned aromatic Piemontese varieties. In these parts, it’s all about punching power inside of this lightweight division.

We have the 2019 Barbera d’Asti “La Martina” finally arriving. It’s been more than two years since we ordered Barbera from these guys (and that’s what they specialize in!) because the last order of 2018 landed a month or two after the shutdowns of 2020 began. Unless you’ve been living under a rock for the last few years, you already know 2019 is a simply fabulous year for Piedmont. Wines like Barbera, known for their intense acidity, found their heights in this long and steady growing season (at least for my palate, whereas many growers here prefer the even hotter years for this grape) that helped the grape phenolics balance out this variety’s naturally high acid. Organically grown on calcareous sands and clay, the vineyard, La Martina, is in a very cold section of Asti and makes for a special profile mixture of crunchy but ripe, palate-staining dark red and purple fruit. It’s aged only in stainless steel, so you can expect notable purity here as well.

Crotin’s 2020 Freisa “Aris” is made from this nearly forgotten grape variety that was ubiquitous in Piemonte only decades ago. Today, it’s been relegated mostly to the region’s backwaters in the wake of the mass propagation of Nebbiolo in Piedmont. There are still compelling examples to be found at cantinas like Brovia and Giuseppe Rinaldi, but perhaps with the ever-increasing demand for Barolo and Barbaresco, it won’t regain footing in the Langhe anytime soon. Nevertheless, it should be on anyone’s radar looking for more of the identifiable but difficult to describe Piemontese characteristics imprinted on all of its wines. From year to year, Freisa can vary in its tannin levels and if not managed well it can be a beast, but at Crotin’s Aris vineyard they’ve tamed it and it brings great pleasure with only a slight tilt toward its natural rusticity.

Over the pandemic, the Russo brothers came up with a new wine bottled in liters: 2020 Vino Rosso Contadino “Beverin”. The label is totally different (more fun!) than the others in their range and it is certifiable Piemontese glou glou, by design—not a typical wine style for this very traditional region! It’s a blend of 80% Bonarda (the fiesta grape) mixed with 10% Freisa (the curfew police for the Bonarda party), and 10% Grignolino to bring more elegance and beauty to the scene. Beverin is Piemontese dialect that implies “a light and easy to drink wine.” I took my first sample bottle to a tasting in Portugal with some of our producers there and it was a favorite for all who tasted it. For the price and quality, it’s tough to beat for those looking for a glass of Piemontese deliciousness.

New Arrivals: France

Patrick Baudouin, Anjou

I finally made it back to the Loire Valley three weeks ago after an almost three-year absence! Crazy! Last summer I hit the road for six weeks straight at the end of spring and into the early summer and missed only the northern part of Champagne and all of the Loire Valley before the fall Covid restrictions started to complicate things again. It was strange for me to miss this part of what has been my usual wine route because over the years I often stopped there twice in the same year. Now, one hour and twenty minutes on a plane from Porto drops me right into Nantes, making it one of the easiest trips from Portugal. It was a great tour and nice to finally see our friends there. I took some days in Saumur and then a few in Montlouis (some very cool things coming from there a few months from now!) and finally hit Patrick Baudouin on my last day before flying back home.

Since I saw Patrick last, he seems to have swapped out his old crew for a group of younger workers in the vineyard and cellar. I’m sure this will influence some of the wines in the coming vintages. Months prior to the pandemic when those nasty tariffs were imposed, we had an order waiting to set sail from this natural-wine guru and somewhat controversial Loire Valley winegrower. The order was suspended and then the pandemic hit. We added a few more goodies but managed to maintain some quantity of great wines from 2015 and 2017.

The first wine is Patrick’s 2019 Anjou Blanc “Effusion”, a Chenin Blanc grown on a mix of a few different parcels of vines on metamorphic and volcanic rocks, the latter formation was the inspiration for the name of this bottling from “effusive” igneous rocks, magmatic rock that cool on the surface of the earth instead of underground, which are known as “intrusive” igneous rocks. We historically import the highest volume from Patrick, so it may be the most recognizable. It’s made in a simple way, as are all the dry Chenin Blanc in Patrick’s range, with barrel aging mostly in older French oak with very little intervention. I find that all of Patrick’s wines go down very easily, but Effusion is the one that performs its best melodies in its younger years, and that’s why it’s always released earlier than the others, along with Les Fresnaye, a vineyard that has seen a lot of trouble in the years from frost.

Volcanic ash rocks from one of Baudouin’s vineyards for his Anjou Blanc “Effusion”

Produced from Chenin vines planted in 1947, the 2015 & 2017 Anjou Blanc “Les Gats” bottlings represent perhaps Patrick’s highest level in his range of dry Chenin in this neck of the woods, on the left bank of the Loire. The others may equal it, but Les Gats carries a few x-factor notes that in my opinion often separate it from the others. The other dry wines in the range are maybe a little more predictable in some ways, whereas Les Gats, even once you think you know it, somehow reveals a new secret with each vintage. That is the case with these two very good Chenin Blanc vintages, and to have them side by side in a tasting shows the merit of these two stellar years and the talent of this northeast-facing site grown on ancient schist that dates to Pangean times. Les Gats is raised mostly in older barrels (perhaps with a new one slipped in there occasionally) and is always released quite late. The 2017 is the new release and the 2015 was a wine that I requested before the pandemic that Patrick held onto for us. The quantities of both wines are minuscule, but at least we finally have some!

We wanted to bring in some stickies from the Loire Valley because there is a small but growing interest again in the category. To work with Patrick on these wines is always a pleasure because they are typically quirky sweet wines, but under Patrick’s direction of natural methods in the vineyard they take on a few lesser-known layers in this part of the Côteaux du Layon, an area that is largely chemically farmed. The 2018 Côteaux du Layon “Les Bruandières” grows very close to the borders of Quarts de Chaumes, the most famous sweet wine appellation of the Loire Valley. Historically, Les Bruandières was on equal footing as Quarts de Chaumes but was not given its own appellation, perhaps due to its very small size? Les Bruandières is a fabulous sweet wine in the sense that it’s not overwhelming with too much sugar. I even sometimes find myself drinking it at a still-wine pace, like drinking a fabulous German Spätlese or aged Auslese, because the balance is gorgeous. It’s perfect for tasting menus when the dessert or cheese course needs something sweet, but it’s not overbearing after an extensive meal and at a time when palate fatigue (or disinterest in more wine) begins to set in.

The 2015 Quarts de Chaume “Les Zersilles” is a very different story than Les Bruandières despite also being a sticky. It’s denser and darker in color, and serves a very different purpose at the end of the meal (I cannot imagine having it at any other point in a meal other than the end!) geared toward a more decadent finish. In contrast to some of the profound, sweet Auslese and TBA wines of Germany, this purely Chenin Blanc wine exists in a more deeply earthy, damp, and herbal sweetness—almost like a Sauternes (I haven’t written that word for almost two decades!) without the aristocratic gold trim and aim for perfection; like us, Patrick prefers the perfectly imperfect wines. Here, in Patrick’s Les Zersilles, it’s a berry selection; not a selection of berries that are totally free of funk, but rather full of the good funk! The quantity of this wine is even less than the others and is meant to be for the many restaurants with tasting programs looking for truly organic and naturally made, high quality sweet wines.

Patrick Baudouin