Carole Kohler – Jardins de Fleury

Short Summary

Full Length Story

Sometimes you know instantly when you’ve gotten lucky, again. Like my first Lambert Chenin from Brézé in 2010. Thierry Richoux’s 2006 Irancy with the Collet family over dinner in Chablis. Veyder-Malberg’s first Wachau wines at his house in 2010. My first Dutraive Fleurie in New York, in 2013, poured blind by my friend–a true sommelier, Eduardo Porto Carreiro. Cume do Avia’s 2017 Ribeiro reds over lunch in Sanxenxo. My drop-in visit with the unknown Daniele Marengo was at his family’s cantina in Barolo. My first two wines from Carole are part of this list.

When I first tasted her enchanted forest, biodynamic, baby-vine 2022 “Source” Chenin Blanc and 2022 “Jardin” Cabernet Franc, I thought, “These are too good.” I yelled to my wife from the kitchen while preparing dinner, “It’s impossible that no one works with her in the US … You won’t believe them. They’re crazy!”

My tasting notes were filled with exhausted references to the great producers in every other sentence. I’ll spare you what would seem like hyperbole and all-to-often exaggerated comparisons to the world’s elite everyone uses as context to sell their new wines these days, but let’s just say that Carole’s are aligned with the world’s best raw wines—no direct references needed.

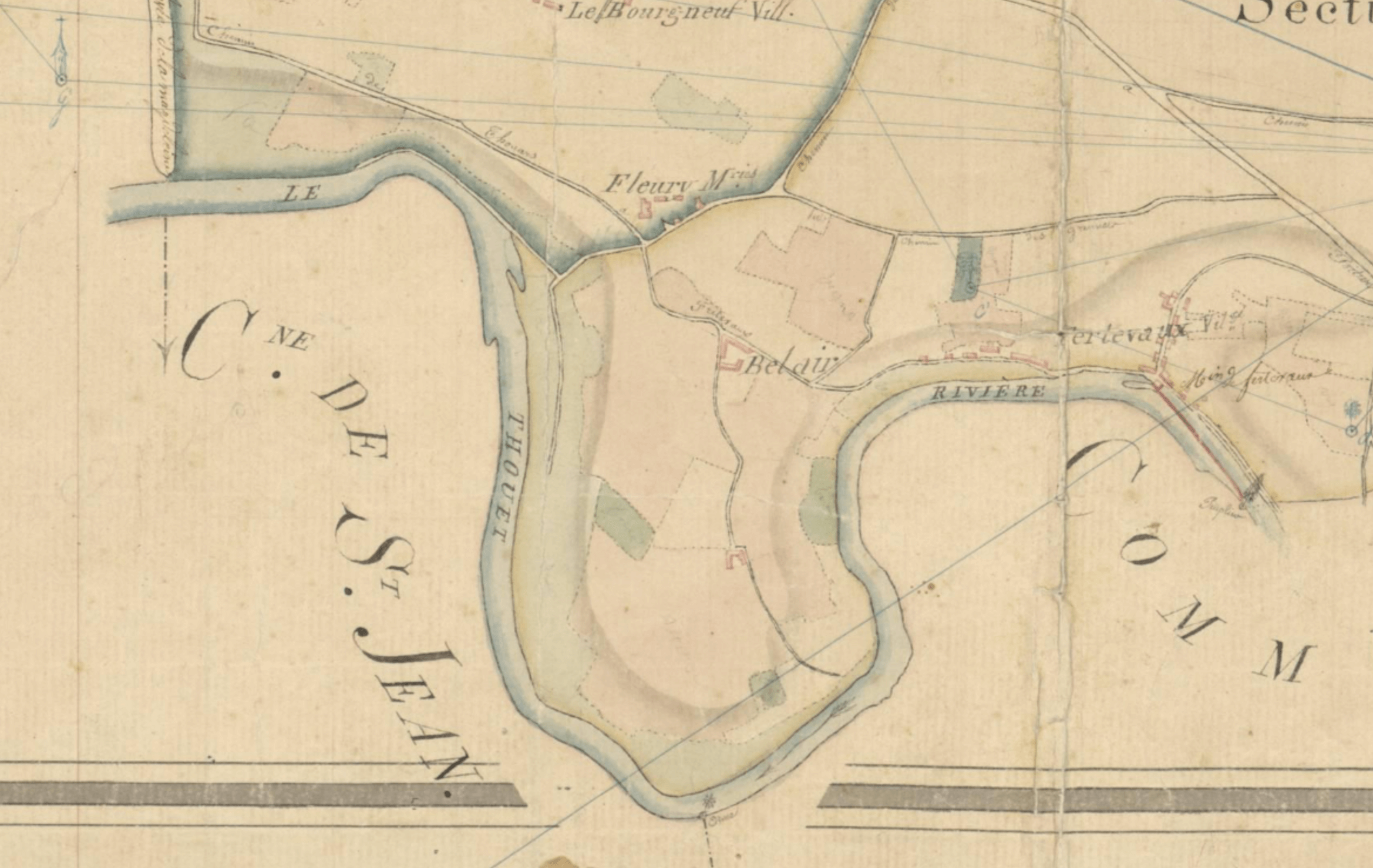

So why hasn’t anyone snatched the place? First, it’s new—well, kinda. Fleury does have history, though it might’ve been forgotten for a while. Carole’s viticultural renaissance of Fleury, an estate documented back to 1458, and then again in 1753 as a fiefdom (land grant from a lord) of the Dukes of Trémouille, began in 2016 with its first vines rooted since at least the 1960s. Registers kept in the Municipal Archives of Thouars demonstrate that vines were cultivated in Fleury long ago, with the oldest registered in 1930. But many European registers for various things were only started sometime in the 1900s, to make sure people planted with American rootstock, and to fall in line with incoming appellation laws, among other things, but most importantly the desire to have a greater tax regulation on wine. We’ve seen this a time or two with old vines in certain areas, like Spain’s Jimenez de Jamuz, whose register says that all the old vines there were planted in 1930, but the locals know they’re much older—some pre-phylloxera.

Secondly, it’s located in the greater Anjou AOC and almost nobody is poking around on the edges away from the most celebrated areas of Anjou, like Coteaux du Layon, or Savennières. This generations-long family home of her husband, Brice Kohler, is a dull 35 minutes south of Saumur center, 30 from Brézé, and 22 minutes from Puy-Notre-Dame. It seems to be the last area to discover on the frontier of the appellation for quality wine. The vineyards are in the former Vins de Pays Thouarsais, an appellation discarded decades ago during the EU’s consolidation of appellation regulations, along with most of the interest in this once-important wine region before phylloxera. Today, it’s lumped into the generic “Anjou” appellation, and the Kohlers forgo the appellation altogether in favor of an even more generic Val de Loire appellation, to be even a little more self-exiled. Many vineyards in Thouars were destroyed in 1964-65. The government paid owners to uproot because they were at the gates of an expanding city, with many pre-empted to build the city’s bypass and large commercial and residential areas. This all seems like such a blasphemous offense to Dionysus, and they were surely punished for it as the wine trade basically disappeared.

The financial incentives of the time were too low, the same as in most of Saumur’s generic appellation until the last ten years. If you hadn’t recovered twenty years after WWII ended, maybe it’s time to move on. History shouldn’t be forgotten, and at Fleury, it wasn’t; it was recorded quite well. It only needed the right people to dig up the records.

Fleury was established in the 15th Century around its constantly flowing spring between the front gate and the house. Joined at its western hip to the ancient city of Thouars, the 16th Century house is quaint, well-kept, remodeled timelessly and full of artifacts, and beautiful art that hardly leaves an open space on the walls of this idyllic storybook countryside manor in France’s north. There’s a maze of cellar underneath, a small, freestanding winery installed in one of their old storerooms and animal shelters, a beautiful, long greenhouse dating back to 1870-1900, 19th Century gardens and a sizeable amount of ancient indigenous forest (suggested by Carole as perfect for Shinrin Yoku—Japanese “forest bathing” to clean the mind). Some exotic trees were planted through Brice’s family of five resident generations (including a sequoia in 1877), an untamed and undeveloped riverfront property, and an extensive horse pasture where Finley and Léon spend their days grazing. It’s almost too perfect with its separation from all other agricultural fields by trees, and without another vineyard even close. Its four separate vineyards gain a unique and lively biodiversity without neighborly intrusions from possible conventional farming activities disrupting her organic and biodynamic practices. It’s hard to imagine that when people figure out how good her wines are some of them won’t also consider planting around Thouars.

Perhaps a third reason she was overlooked was that 2018 was Carole’s first year, ever. The 2020 and 2021 wines they opened to taste along with the 2022s and 2023s were well beyond just that glimmer of misdirected brilliance and the faint, familiar scent of a gifted terroir somehow overlooked. But I didn’t find the same level of clarity as the 2022 Jardin and 2022 Source. Something else clicked in 2022, perhaps they just needed five years to find that line.

And then there is Carole Kohler, the subject of a Klimt painting who slipped her frame. In constant reflection of light in motion, seemingly unaware of the energy with which she fills every room and every vineyard she enters, she leans in, listens like it matters, and smiles easily. There’s no distance with her, no pretense, no guarded elegance. She cooks with inspiration. There’s so much art and sculpture in their house that everything seems to be alive and moving. She’s an avid reader, skier, runner, swimmer, and yogi. “I also like meditation, sewing, decorating my house, and taking care of my flowers and my family.”

After her university studies where she attained a Master’s degree in Chemistry followed by fifteen years in the agri-food industry, Carole felt it was time to “Reconnect with the living and give meaning to life … to live with the rhythm of the seasons, immerse myself in nature, produce a local and shared wine and work to guarantee the sustainability of the Domaine de Fleury, owned by my husband’s family for five generations.” She added, “I can’t really explain why it was like a little voice telling me that I will be happy doing that…” Committed to her newfound idea (and giving in to the voices in her head), she went back to school, attaining a diploma in Viticulture at Montreuil Bellay, just twenty minutes north on the way to Saumur. During this time, they also had their selected plots analyzed through pits and generated detailed geological maps and bedrock and topsoil compositions of what they stood on before they began to plant.

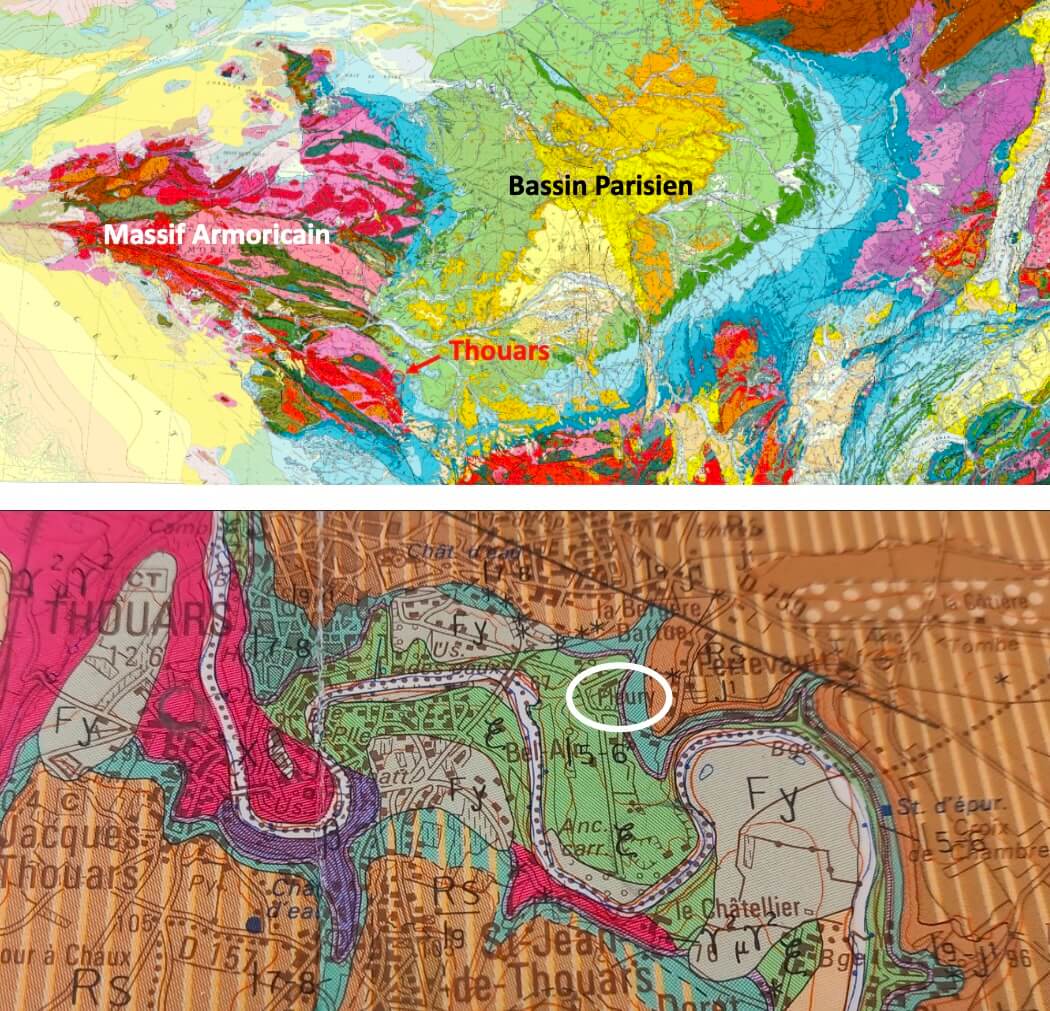

A working architect by trade, Brice met Carole through his sister when they were teenagers and is the other half of the dream to revitalize cet endroit extraordinaire. His desk overflows with a collection of ancient, illustrated maps and today’s geological research of the area that supports its rich heritage as a transitional center of the Massif Armorican and the Paris Basin, copies of vineyard registers, documents of Fleury’s history as a fiefdom and declarations of harvest from the 1930s. Together, they shared the same curiosity and belief that this was indeed a place!

A walk inside Fleury’s vineyards is a walk in what seems like virgin green land flowing uninhibited with yellow, purple, pink, and red indigenous flowers and a multitude of competing grasses that make it hard to walk through the fields before their annual plowing. These flowers are usually only around during the months one would expect, but as mentioned in last month’s newsletter where we covered the portion of our trip in Spain, there were also spring flowers in bloom in the Loire Valley mid-December! Carole notes that when the vines are young, they need more plowing to ensure the root systems head downward instead of sideways. Tree groves abut each plot, bringing an orchestra of fresh wind and foresty smells with the constant rustling of leaves and the buzz of bees and bugs.

After Jardin was planted in 2016, Source was planted in 2017 entirely to Chenin Blanc on a single 0.7-hectare parcel at 70 meters altitude. It sits across the little one-car road, Rue de la Mare aux Canards (Duck Pond Street), which marks a clear separation of the acidic rock of the ancient, Pangean-era Massif Armorican from the alkaline limestone rocks of the Paris Basin. On the south side is the 570-million-year-old Precambrian quartz-rich schist and micaschist outcrop above the Thouet River, and on the other side, the white limestone. This is evident on the road’s walls, cleverly distinguished by its builders, who built the southwest wall with the dark gray and green schist from that side and white limestone (an occasional dark blue schist for accenting) on the northeast wall.

Named after the spring that led generations to inhabit the space around it now known as Fleury, Source is dynamic and quite distinguished from the other Chenin Blanc on the property, Séquoia. Its topsoil is rich in quartz and grey schist with clay on a green and black schist bedrock. This is an explosive white with more muscular, mineral-heavy lines. The 2022 was fully matured to 13% potential alcohol before picking and is a must-try from this domaine as it represents what is possible with this extremely talented site. By contrast, the 2023 was picked very early because of vineyard challenges from botrytis in September. Carole explained that with its proximity to the river, only 50 meters away, and the thick forest in between, she couldn’t wait another day for fear of losing too much crop to rot. It was picked, not chaptalized (as so many would do without a second thought), and bottled with 10.5% alcohol. Even with this low degree of alcohol, it offers extremely fine lines but without the same explosive solar-powered energy of the 2022 version.

Just a hundred meters east of Source are the two parcels planted in 2019 that constitute the 1.5-hectare plot of Chenin Blanc for Séquoia. Once again, we are in the Pangean remnants of the Massif Armorican with a topsoil of clay and decomposed schist and quartz on very hard green mica schist bedrock. With only a few vintages to draw from, Séquoia appears to be more linear and finer than Source, in general. It’s not as explosive but offers a distinct contrast, indeed worthy of bottling separately.

The 2022 Source was whole-cluster pressed and naturally fermented in 30-hectoliter steel tanks for four days at a maximum of 23°C and completed malolactic fermentation. It was bottled with no added sulfites and was not fined nor filtered. The 2023 Source and 2023 Séquoia went through the same processes as the 2022 Source, except that they were aged in 12-hectoliter clay Vin et Terre amphora and old 225 L French oak for eight months before bottling with 10 mg/L of total added sulfites. Neither were fined or filtered.

As good as Carole’s Chenin Blanc wines are, her Cabernet Franc hooks you immediately. Incredibly alive and full of energy, its red and black fruit profile has a lean fleshiness snugged up and narrowed by a garrigue-like floral bouquet of lavender and flowering wild thyme and a core of deep earth and virility. It’s complex and hard to square that it comes from a half-hectare of baby vines planted in 2016. This is the fruit for Jardin, whose vines sit on a mild slope facing west on the Paris Basin side of this geological convergence. While there are both Jurassic and Cretaceous limestones in the greater Anjou area, the bedrock here is what geologists call, Toarcian (named after Thouars!), from the Early Jurassic dating to around 180-million-years ago. This hard clayey limestone doesn’t share much in common beyond its dense calcareous materials with the Loire Valley’s much softer sandy tuffeau limestone, though it does have some sandstone interbedding. It’s less pure in calcium carbonate, and more relatable to the limestones of the Côte d’Or, though it predates the Côte d’Or’s predominant limestones by around ten million years. It’s like Bathonian, Bajocian, and Oxfordian, among others, though Toarcian limestone may be found in some appellations—and Chablis’ Kimmeridgian marls are about thirty million years younger, while Portlandian limestones predate it by about forty million years.

The upper section of Jardin sits at 90 meters with shallower rocky topsoil of silex, limestone, clay and sand before striking a hard and fairly siliceous limestone bedrock (in this case, with black flint/chert) at 30 cm below. The topsoil deepens lower on the slope reaching down to below 80 cm where some influence of the river is apparent with deeper alluvial topsoil, making it a longer but easier journey in search of limestone bedrock. All this is to say that Jardin is complex, and some of that complexity could be attributed to its geological diversity inside this small parcel.

Jardin is destemmed and naturally fermented in 50hl stainless steel tanks for 15 days with no extraction movements (infusion method) at 25°C maximum. It’s then aged eight months in old 225 L French oak and concrete eggs and bottled with no added sulfites and without fining or filtration.

The world needs Cabernet Franc rosé like a vigneron needs late spring frost. But Carole’s rosé is bottled summer sun. I never thought a Cabernet Franc could render such a dainty, attractive beauty. It’s soft and pretty, lifted with pink rose petal and taut stone fruit skin, just the right touch of amare from the light extraction and thrust from Cabernet and Chenin picked just a touch earlier than grapes for her other wines—an equal mix of both varieties.

Whole-cluster pressed, naturally fermented at a maximum of 18°C for a good balanced fruit and savory notes, and aged for six months in 12-hectoliter fiberglass. It undergoes full malolactic and has no added sulfites, finings or filtration. The Cabernet Franc portion comes from a single 0.3-hectare parcel planted in 2020 at 75-80 meters altitude, just across the Rue de la Mare aux Canards and slightly uphill from Source (where it takes the Chenin Blanc of the blend) it’s on a mild slope facing southwest. Across this one-car street, from the first Chenin vine to the first Cabernet vine, the mica schist soil of Source changes to Toarcian limestone bedrock and clay topsoil—Precambrian Massif Armorican to Jurassic Paris Basin, a 360-million-year geological swing in less than ten meters.