François Delaunay – La Lande

Short Summary

Full Length Story

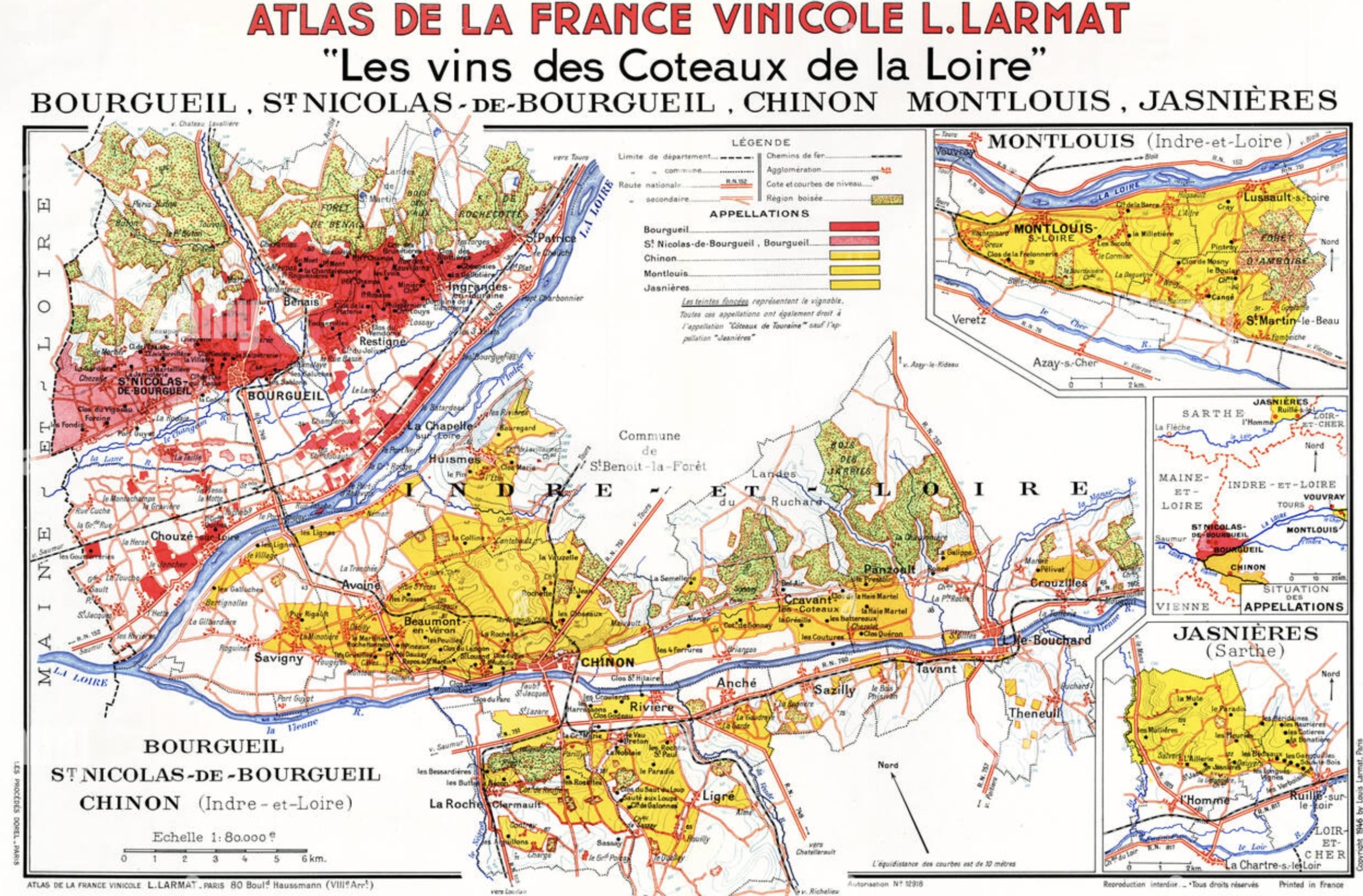

Domaine de la Lande comes from the humble and nearly forgotten Loire Valley appellation, Bourgueil. Operated for the last few decades by François Delaunay after his father handed him the reigns, the now organic (certified in 2013) Domaine de la Lande maintains spectacularly priced wines that simply overdeliver with an extremely classic sensibility. Full of flavor, François’ wines rewind the clock to my first encounters with Cabernet Franc, which, almost thirty years ago, was an esoteric variety in the States thought best blended rather than as a monologue performer. Cabernet Franc from Chinon, Bourgeuil, Saint-Nicolas-de-Bourgueil, Saumur and Saumur-Champigny remain some of the world’s best deals for legitimately great wines. Even the average ones are higher than the average from most famous appellations. The most common Loire Valley Cabernet Franc can age well, if not more consistently than most Burgundies two or three times the price. And while the wine world continues to flirt with new styles in each area and decade-long trends, some, like François, have wedded themselves to traditionally and simply made wines.

With the first sample bottles I received, I knew by the aromas alone—rustic but clean, deep, balanced between darkness and light—that they were for me. I admit, I’m an aroma hound first, texture second. My first visit with François this last December brought my enthusiasm to new heights, and my second only three weeks ago was reassurance that it wasn’t a fluke. My first cellar tasting last December was on point, followed by a quick vineyard tour of the well-tended and thriving grounds, still green even in December. But it was in the ancient tuffeau cave with old bottles that I understood the true quality of this domaine and was reminded of the breed of Bourgueil.

At the top of the slope near the forest, we pushed through thick bushes, ducking under an overgrown tree and into their hidden cave. Entombed in the milky white tuffeau cavern were vintages as old as François, with bats quietly sleeping before slowly unraveling like old wines as they stretched before flight. As with many of us, one of my greatest pleasures is old wine that’s still sound. Well-aged wine is the final frontier of wine appreciation, a test of pedigree and clairvoyance (and sometimes vindication) of its maker. Most “taste” old and celebrated wines with too many people for a single bottle, which works as an academic snapshot, or often to fluff their experiential inventory to be later embellished in recounting, as though a taste is enough to know a wine. “Tasting” a great bottle is wasting a great bottle. Great wines reveal their merit when drunk over enough time—at least until the conversation starts to go downhill. The worst tastes of a great wine are the first, or the mud in the bottom. It’s everything in between over a time where one really gets to know a wine’s true character and breed.

I’ve long collected wine to age. In the late 1990s, I worked at Restaurant Oceana in Arizona, with its chef, Ercolino Crugnale. He moved there from California with an extensive collection of mostly California wines he intended to put on his wine list, only to find out that he’d have to sell them to a distributor first and have them sell them back to keep things legal. He decided to drink them all instead. He was, without a doubt, the most generous restaurant owner I’d ever worked for. He had all the California greats from the 1970s-1990s, the highlights for me being Ridge and especially Williams Selyem. His pleasure was sharing as much as drinking the wines themselves. And we definitely didn’t taste. We drank. And that’s when I fell in love with old wine. Williams Selyem was the first great influence after flirting with the world of cheaper wines—the price point I could afford to drink. I was fortunate to spend a lot of dinners in Santa Barbara and Sonoma with Burt Williams, from Williams Selyem, during his last five years when he brought out mostly magnums because he’d run out of 750s. Darn.

In the mid-nineties, young and ambitiously curious wine freaks like me weren’t easily allowed into the exclusive “wine club.” I was dismissed regularly by older wine professionals who guarded wine knowledge like gatekeepers, bestowing to the worthy (but moreso those who kissed the ass the most), or to the guests they schmoosed. Never one to kiss the ring (and not so humble about it either) I walked my own path until I met Ercolino. The other most generous boss I ever had was The Ojai Vineyard’s, Adam Tolmach, with whom I worked in the cellar for five seasons and remain good friends.

There are few wine experiences like old wines crafted by generations past that then go unmoved in silence and darkness for decades deep inside the cold, damp earth. It’s incredible to think that some of the wines that had been guarded perfectly for decades before François opened them were destined for my glass that first day I visited Domaine de la Lande. It’s humbling, and a special privilege that I can’t say I felt I deserved. Yet, I could cite countless examples of having experienced that sort of kindness and hospitality in the wine world.

Back in Portugal, I messaged François about possibly buying some old wines—a mixed case or two, I begged … I could see François’ lean, rosy high cheeks pressed up as he smiled and typed a mile-long list of options with every vintage back to 1982 that he sent me a few days later. The list was thorough, the prices jaw-dropping—a mere $0.50-$0.65 for every year aged in the cellar; top years, $1.10 for every year. I scoured the web for vintage charts but came up short on information for Bourgueil. I asked for guidance, which François gave. I proposed four mixed cases off his list: some very old that I would try immediately and other young ones (2005-2015) that I’d cellar longer. So far, I’ve pulled the cork on about ten bottles (1985, 1988, 1989, 1990, 1993, 1996, 1997, 2001, 2002, 2005–and there may be a couple I’ve forgotten), and each has been glorious. Most I shared with our Portuguese grower and great friend, Constantino Ramos, who is also now obsessed with them. The only confusing moment is just after the cork is pulled. No bottles had been capsuled until François’ family readied them for me; they’d all been left exposed to that ancient cellar, some for as many as four decades. The top of each cork was moldy and smelled like the deepest corner of the cellar and even a little TCA, quite rotten. But none of the wines were corked! The bottles only needed their lips and inside the neck cleaned, where the cork was in contact.

Bourgueil has long been overshadowed by Chinon, at least in the US market–maybe because it’s easier to pronounce? With all those vowels, Bourgeuil is tough to get right! Bourgueil and Saint-Nicolas-de-Bourgueil (SNdB) are on a contiguous slope on the north side of the Loire River. Chinon is more topographically diverse and mostly sandwiched between two rivers (the other being the Vienne), like Montlouis-sur-Loire’s vineyards are between the Loire and Cher. Perhaps Bourgueil is viewed as more rustic than the typical Chinon. Perhaps a matter of more gravelly and sandy sites in Chinon?

Without a classification system in place, location is an important variable. The pedigree of each vineyard bearing this appellation name can be quite different from the next. There are wines for easy drinking and others far more serious. Looking closely at a Google Earth image, or an appellation map, the land near the Loire River has fewer vineyards than other crops.

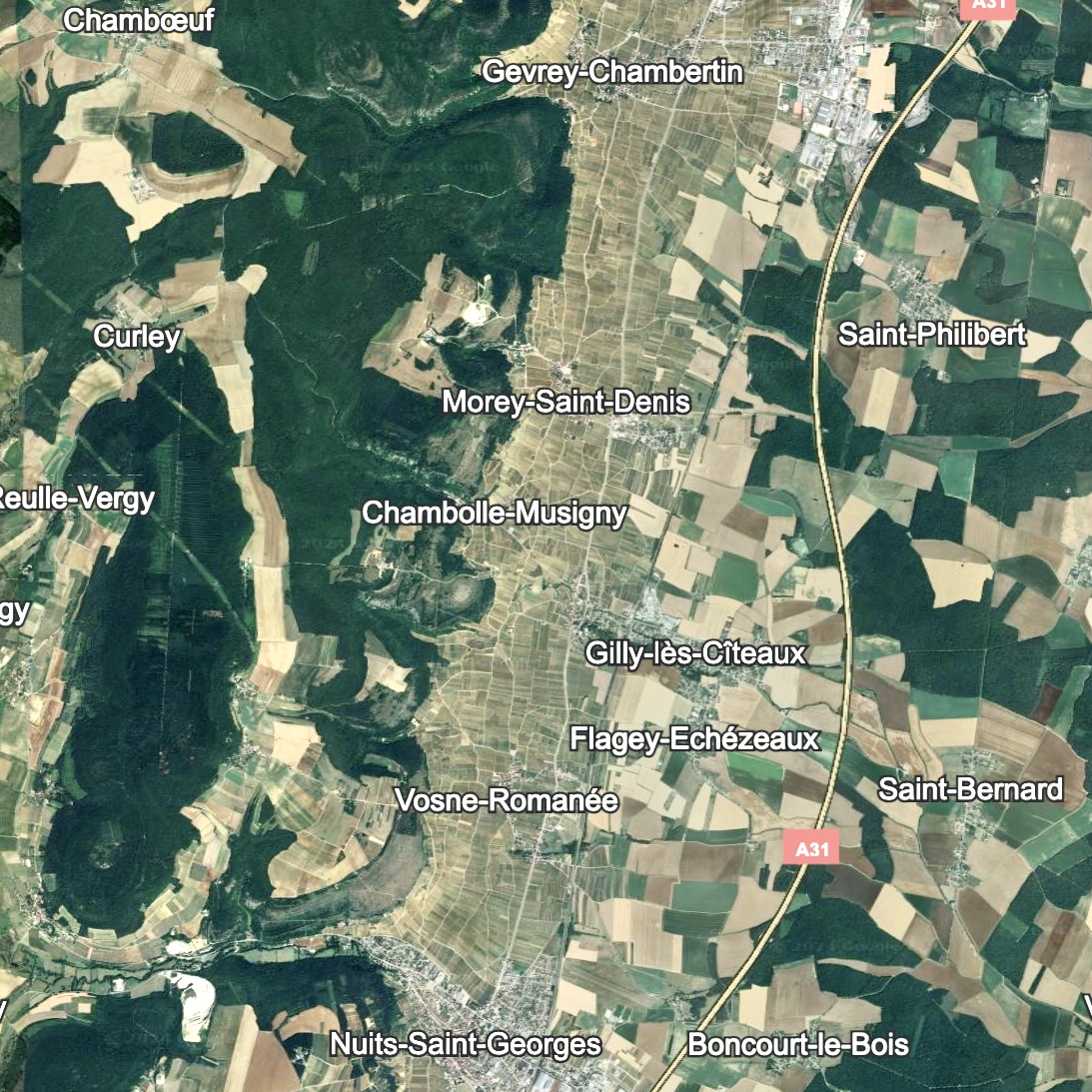

Bourgueil is split in two by the small creek, Le Changeon, and from a 20,000-foot view, along with the SNdB, the contiguous slope is like the Côte d’Or and many Champagne areas, only facing south and southwest. Many of Burgundy and Champagne’s top spots favor more eastern expositions. Given its abundance of pyrazines, Cabernet Franc historically required more late afternoon sun, so more south/southwest positions. These days, it ripens quite easily regardless.

The lower slopes of Bourgeuil and SNdB are generally sandier, and those on the riverbank have more unsorted alluvial sand, silt, clay, and gravel. About 4km north of the Loire River toward the forest, a gentle uptick begins from 40m, peaking around 90m. The top sites for wines of pedigree sit higher on the slope, close to the forests, where roots make contact with more of the tuffeau limestone bedrock and calcareous clay. François’ family vines begin just north of the village on the western end of Bourgueil at about 50m with more clay than sand and move upslope with the oldest vines destined for the “Prestige” bottling.

In short, the Bourgueil comes from six hectares planted between 1965 and 2010 at 50-60m facing south on a gentle hill of tuffeau limestone bedrock with a shallow siliceous clay topsoil. This is the easier-going wine, fresh, beautiful, and lifted with a substantial follow-through. It’s a great wine that will improve your day when you need a fair-priced, terroir-laced organic wine that doesn’t make you work too hard to find its cultural and regional stamp.

Lucky for you, we were able to buy both the 2015 and 2017 Bourgueil “Prestige.” This is their superstar wine from two excellent and balanced vintages (from the same vineyards those old wines that I bought from François grew and then aged so long in the cellar). They are also their current releases—it’s nice to have some age built into a wine program! Prestige is more profound and substantial than the appellation wine. It’s equally classic in style, and just as fun to drink, but in a heavier weight class (though more a tight-lipped-but-fluttering Ali than a bruising Tyson) flowing with waves of complexity. Also facing south on a gentle hill of tuffeau limestone bedrock with deep calcareous clay topsoil at around 70m, this two-hectare plot was planted between 1930 and 1964. These old vines give it its torque and the organic culture for more than two decades now, its vivacity. The 2015 is for those who want more meat on the bone, while the 2017 is only a little more lifted and still quite substantial.

All François’ Bourgeuil wines are made in a very straightforward manner. They’re fully destemmed and fermented/macerated for around two to three weeks with one punch-down and one daily pump-over. Then they’re aged 18 months in old 5000 L French oak foudre and steel, with light filtration but no fining.