Fattoria Zerbina

Short Summary

Full Length Story

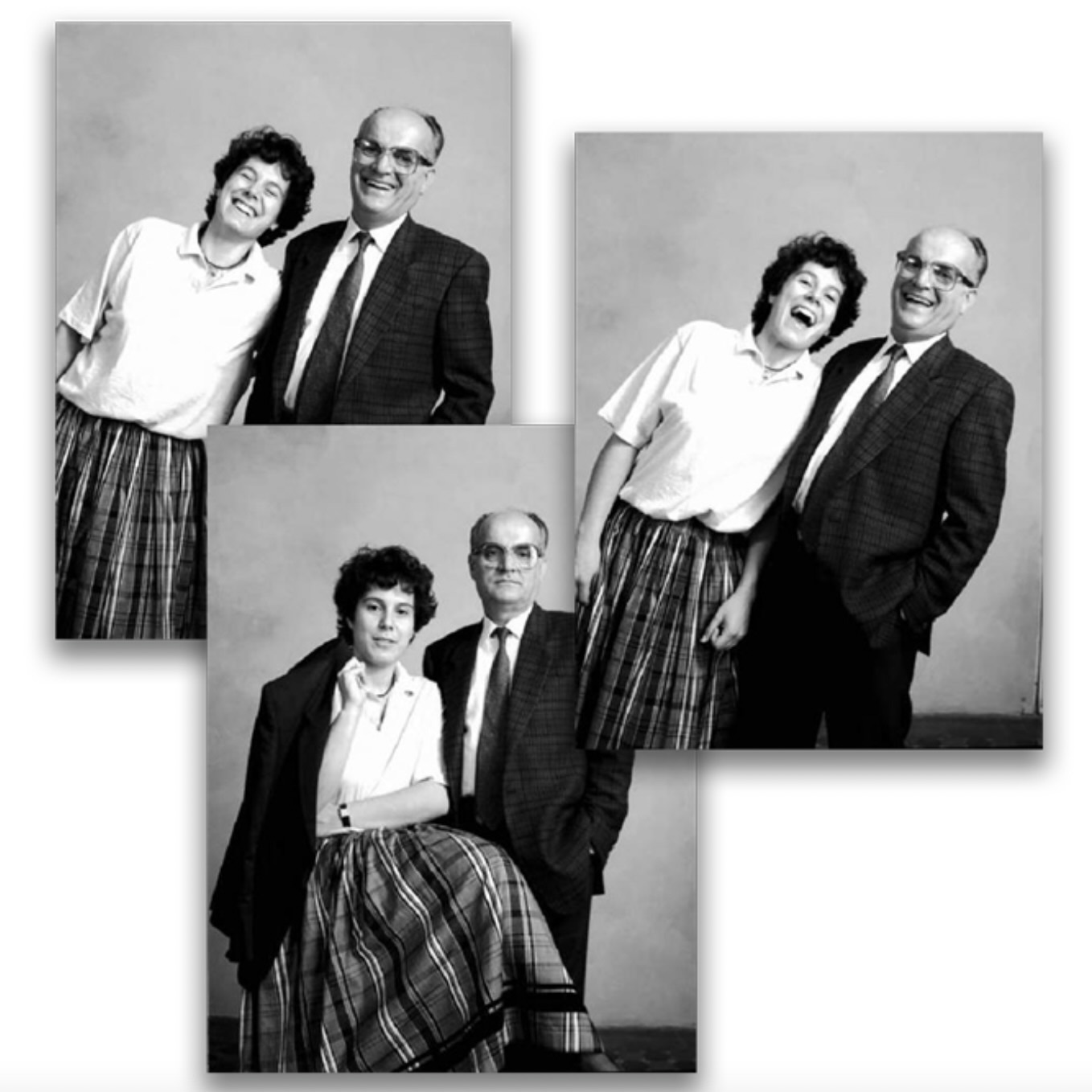

While neighboring France began to gradually open more space for women in its professional winegrowing circles, Italy’s opening remained slower. Constraints by traditional structures through the Catholic Church and rigid family hierarchies with deeply rooted cultural patriarchy meant that, at the time, women were largely behind the scenes. In industries like wine, women in lead roles were not only uncommon, they were nearly unthinkable. Thus, Cristina Gemignani’s decision to accept the reins of Fattoria Zerbina from her grandfather, Vincenzo, was quietly radical for the mid-1980s.

Rather than seeking fanfare or framing her role ideologically, Cristina immediately focused on quality and a readiness to challenge assumptions—not only in Italy’s societal norms for this métier, but in the potential of Vincenzo’s vineyards in the backcountry of Romagna. Among just a few other women in her time (like the young Elizabeth Foradori, who also led her family’s winery in the 1980s), her success signaled early stirrings of change in an industry that hadn’t yet begun to make much space for women in leadership positions. (Another advance for Italian women in wine that surprised me is when I met Barolo’s Virna Borgogno, where I learned she was the first Italian woman to attain a degree in Enology in Italy. That was as recent as 1988.)

Regarding her new station as the director of this family estate in 1987, Cristina said, “At the beginning, there were some headwinds, especially in the vineyards with the team and the new methods to handle the different canopy and the green harvest. But in general, I was lucky and happy. There were never problems on the commercial side.”

The clearest argument for Cristina’s place, any winegrower’s place, is found in the quality of the results. Her relentless toil delivers a range of exceptional wines that begin their picking in August and end with meticulous berry selection of botrytized Albana in the late fall—immortalized in vinous form. It’s a steadfast work, and she appears to pull it off effortlessly, though we know it’s far from effortless.

An early Francophile, Cristina visited Bordeaux at 22 to learn French and tasted her first Sauternes. It was Château Suduiraut, and it was the catalyst that encouraged her to learn more about the subject and immerse herself in the world of wine. That Sauternes also stimulated her interest in sweet wines, and she was lucky enough to have the uniquely versatile and nearly extinct Albana as her medium. She’s become one of Italy’s most (or maybe the most) prominent desert wine growers.

Before jumping into Zerbina, Cristina eventually finished her agronomy degree in Milan, and, already fluent in French, was soon on her way to study at Bordeaux University in Talence. Her professor, Denis Dubourdieu, and his father, Pierre, greatly influenced her future as a winegrower. But Romagna would be this native Milanese’s destination, and Marzeno, a hillside zone on the northeastern edge of the Apennines along the Adriatic, the staging point for her life’s work. “The investment was to change the perception of the estate, thanks to a new type of viticulture and the new style of wines to follow. Beginning with the conviction that the vineyards in Marzeno had a different character and specificity from other areas, our goal was to highlight their salient features.”

There was no formal DOC for Marzeno Sangiovese until 2011, when the DOC Romagna Sangiovese Marzeno became official. Thus, Zerbina’s earliest bottlings (like the 1985 Pietramora) carried only the Vino da Tavola di Marzeno designation. This already denoted a clear thought and idea about enhancing the terroir that would later give name to the current DOC, which is now in use for most Sangiovese wines she produces.

Fattoria Zerbina is on the Romagna side, rather than Emilia, where the riches of the sparkling red Lambrusco, Parmigiano Reggiano, Aceto Balsamico, Prosciutto di Parma, Mortadella, and the pig dominate. The Romagna culture leans into the Apennine hills that begin to parallel the Adriatic in the northernmost end. The people of Romagna are known to be more open-hearted and easier going than the more industrial and affluent Emilians inland toward the west. The fare is less rich than in Emilia and Toscana in the west and south, with more seafood and vegetables to accompany the pasta and meat. The wine is somewhere in between, though without the bubbles. Perhaps more rebellious than their illustrious neighbors in Emilia and Toscana, it’s not surprising that a young Cristina from Lombardia would blaze an early trail with the support of her grandfather in an almost entirely male-dominated Italian wine world.

While shaped by the nearby Apennines, the climate of Zerbina’s vineyards is tempered by the confluence of sea breezes from the Adriatic, just 30 kilometers away and the nearby mountains that peak with Monte Falco at 1,658 meters, which lies about 45 kilometers south from her vines and 40 kilometers from Florence to the west. She notes that despite the Apennines behind them (home to the famous Chianti hills and Montalcino further south), the mountain influence is mitigated by the presence of the sea and its salty winds—another crucial difference between these Sangiovese producing areas.

Zerbina’s vineyards stretch across altitudes from 90 to 250 meters above sea level on an elaborate patchwork of small parcels with varying exposures and soil types. Cristina says this diversity “makes harvest crazy,” but she also believes it contributes much to her wines’ complexity.

Red clay and limestone are reserved for Sangiovese, a vine that prefers well-aerated soils over compacted ones. Red soils are often rich in iron oxide, as is the case for Zerbina’s, and it’s usually a sign of good aeration. And the high calcium content (especially from the limestone in her vineyards) helps the clay soils to further resist compaction by promoting aggregation. (Science quickie: calcium ions, with their double positive charge, bridge the negatively charged clay particles, binding them into airy, crumb-like clusters that improve drainage and structure. Thus, keeping the clay particles from being impenetrable by water. Low-hanging fruit comparison: France’s Côte d’Or.)

While Chianti Classico and Montalcino draw from galestro, limestone and marl, Cristina’s red clays and fractured limestones, coupled with the Adriatic influence, yield wines with a freshness and open-armed drinkability that set them apart. She explains that their grapes always express a friendly, fresh character across the appellation with simple, smooth tannins, which she says may be the most distinctive feature compared with other Sangiovese producing regions that build on firmer structure in more continental climates and higher overall altitudes.

Other reds on the property, like Merlot and Cabernet Sauvignon, are planted on the more compact gray clay where water-stress levels are higher. In winter, the soil is well-hydrated and cold, but in the summer, the vines become more stressed as the clays dry, potentially breaking root systems, and need more irrigation. Being a poorer soil with lower organic matter, the gray clay offers much less nutrition for Sangiovese but is more suitable for these French varieties.

Not surprisingly, the lifted and ethereal Albana is planted on a fine-grained topsoil composed of sandy and calcareous fluvial deposits. A little deeper down, it becomes rockier and richer in clay.

If the last decade has proven anything, it’s that the real story of Zerbina isn’t just tinkering in the cellar with the wines, it’s adaptation in the vineyards. Cristina says climate change has a strong influence on her decisions. For several years, she’s been trying to develop new techniques in the vineyard and cellar to reduce its effects.

She’s reducing vine vigor, adjusting pruning, delaying mowing, and working the soils with tools that preserve the root zones. Her goal is longevity, in vine, wine, and the legacy of a place that’s finally beginning to speak for itself. As she puts it, they grow vines trying to respect their balance and attitude, trying not to push them too much.

The past five vintages have tested Romagna’s growers, and none more than Cristina.

2020 was dry, punctuated by a miraculous rain in August that saved the vintage. 2021 was preceded by record December rainfall that refilled the soils. 2022, the hottest season in recorded European climate history, marked Zerbina’s first official organic certified vintage and, despite the heat, delivered very good quality. But then came 2023.

Cristina simply calls 2023 the worst season they’ve had in their region. (This is hard to believe if you’ve tasted her 2023 Bianco de Ceparano from Albana!) A violent rainstorm brought 300 mm of water in May, causing widespread flooding and landslides. Later, a July storm with winds over 100 km/h and intense hail destroyed most of the higher elevation production. The vintage was salvaged only for Albana and some base Sangiovese wines. No reserves were produced as sixty percent of the harvest was lost.

2024 became a year of rebuilding. Soils were repaired, pruning restructured, and vineyard defenses reinforced. Albana was picked in pristine health. Sangiovese ripened cleanly, though thin-skinned from the heat. Cristina says only the future will speak about the wines.

Albana, the flagship white of Romagna, is often misunderstood, if it’s known at all. It lost a lot of land to other varieties with, perhaps, a gentler appeal. For this taster, it’s hard to imagine overlooking this grape, as it’s such a talented Italian white variety.

Cristina’s version is anything but obscure. Her style is oriented toward white flowers and citrusy character, vibrant, iodine-rich, reminding one of the presence of the sea, millions of years ago. In still form, as the Bianco de Ceparano, it’s racy, vertical and electric, and one of the most compelling Italian white varieties that seems to match our company palate as well as any white variety in all of Italy—at least in the hands and vision of Cristina. And like Fiano di Avellino and the Campanian varieties, it ages well, and its complexities improve over time.

Planted on fluvial soils of sand, calcareous materials, and deep-lying rock and clay, her Albana achieves natural acidity and remarkable structure. The grape’s late-ripening habit and sparse clusters make it ideal for noble rot. Cristina says it ripens late and has a high sugar content balanced by a naturally high acidity.

In the cellar, Bianco de Ceparano, labeled as a Romagna Albana Secco DOCG (established in 1986, and the first DOCG Italian white wine), is made directly and simply with natural fermentation in steel followed by a half-year in concrete before bottling.

The entry-level Sangiovese wines are as telling as the flagship bottles, maybe more so for today’s market trend, where buyers are interested in the immediately accessible yet serious. Like many growers wise to the times, she is also taking a softer approach to her entry-level range of reds.

They’re almost too perfect in their combination of terroir and pleasure —the only danger is how easily they disappear from your glass. Not typecast as only pleasure bombs, Ceregio, Torre di Ceparano, and Poggio Vicchio reflect not just place, but philosophy: wines that don’t posture. Cristina believes Zerbina succeeds in producing wines, especially the younger styles, that are an incredible magnifying glass of the terroir, with a beautiful intensity of color, with nuances reminiscent of ripe cherry and strawberry with hints of violets, always supported by simple yet present and elegant tannins. They’re juicy and delicious, but also show extremely pure and strictly focused character.

Fermentations are conducted at lower temperatures than the Italian norm, at 25 to 26°C instead of 32 to 33°C. This cooler temperature helps capture more of the fruit notes than earthy ones. Extraction is gentler than in the past, and so is the time on the skins. Historically, they’ve kept extraction quite short and gentle, with lower fermentation temperatures, lighter punching down and pumping over, and sometimes the use of délestage (rack and return). She avoids crushing berries after destemming and prefers to work with whole berries. These adaptations for shorter times and gentler handling have all been realized in recent vintages.

The higher-end Sangiovese wines were more of a throwback in overall style than the entry-level reds, until 2019. The wines Cristina crafted in the past were built to stand up to their Tuscan counterparts, though perhaps always a little more accessible and fruit-strong, even for the style. But in 2019, she recalibrated. In the vineyards, they tried to lengthen the time during the ripening phase by integrating guyot pruning alongside bush pruning in some of the old vines.

Many of them are quite delayed in release time, with Pietramora and Marzieno released about half a decade after their harvest year. They come from the most prized parcels of their vineyard collection and are intended for the longer haul. They spend two to three weeks fermenting and macerating on the skins, followed by a year of aging in 500-liter tonneaux.

Starting with the 2019 vintage, they began to work a lot in the vineyard but especially in the cellar to define a more contemporary and less massive, extracted, old style. They tried to extend the ripening time by integrating Guyot pruning alongside bush pruning in some old vines. Guyot slightly increases the production but also results in smaller clusters, delaying ripening and promoting lower sugar concentration—all necessities in this area with the combination of climate change and Cristina’s desire to evolve toward a fresher style. While in the cellar, they applied the same rules to the vin de garde style as they did with the young wines by reducing the fermentation time of the grapes to two weeks while keeping the temperatures lower, and finally fermenting most of the grapes in tonneau.

We have yet to dive into importing the Albana dessert wines, but we hope to have some hit our West Coast shores one day. The only problem with these wines is that the production is tiny, and she’s built a strong global following for them in recent decades. So, we must wait for our opportunity!