Le Vent des Jours

Photography and writing by Ted Vance.

Full Length Story

After twenty-five years as a sommelier, wine wholesaler and the owner of a Parisian wine bar, forty-eight-year-old Cahors native, Laurent Marre, found himself in a hospital bed. Unexpected life-threatening circumstances and four months confined to a hospital can change anyone’s perspective. After he was released, Laurent and his wife, Nathalie, started to plan a return to Laurent’s familial homeland. Since 2018, they’ve been raising horses (Nathalie’s métier, along with plowing the vineyards) and farming eight biodynamic hectares of vines on their 30-hectare plot surrounded by forest on one of Cahors’ geologically diverse and high-altitude limestone plateaus.

Our first interaction with Laurent’s impeccably balanced, no-sulfites-added “natural-wine” range (white included), evoked a whole-body YES! The range begins with C’Juste, a welcome and unexpectedly intense mineral and fresh, amphora-raised Gros Manseng, followed by a series of emotion-inducing and minerally fresh Malbecs raised in concrete, amphora, and large old French oak barrels and foudres.

No one’s body stays young forever, but at fifty-something, Laurent’s mind seems to have turned back the clock. From the abyss of his hospital bed came rebirth and revelation that brought him back home to Cahors and a dream he had almost forgotten.

Laurent was in line to be the fifth generation of operators of the Cahors hotel and restaurant, Le Terminus. Hospitality, wine, culinary arts and living well from one meal to the next were their family heritage. They took their vacations in wine countries with good restaurants, and it set the course for his adventures abroad. After high school, he attended viticulture and enology university in Toulouse. Instead of jumping straight into the vineyard and cellar, he worked in Alsace for three years at L’Auberge de l’Ill with Serge Dubs, one of his great mentors and the winner of the 1989 “Best Sommelier of the World” competition. Eventually, Laurent owned a wine bar and also represented various vignerons in the Paris market.

“I always wanted to be a winemaker. But not coming from a farming family, my former job as a sommelier allowed me to achieve this dream of working in the wine world. Then a serious health issue in 2016 pushed me to achieve my dream to become a vigneron.”

Put on hold and then nearly forgotten, his original dream took a backseat as he got accustomed to Parisian life where he watched the rest of France and the world passing through the iconic Ville lumière. Now he’s a new-world mind in Cahors’ old-world setting, and there are few vignerons we’ve encountered so sure of their calling to the vines as Laurent.

It’s rare in France for outsiders of the wine community (even if they’re French) to make the leap from life in restaurants and wine bars to that of a vigneron. Laurent is an exception with his quarter century in helping to promote young vignerons’ names and reputations in Paris and elsewhere. With full idealism intact, his splash was immediate and perhaps surprising to some. But it wasn’t for those who are familiar with his immeasurable urgency to live life that followed years of reflection on the nature of wine, and the words and ideas of the thousands of vignerons, sommeliers and talented tasters and thinkers who crossed his path. With clarity in his practice, his ideas have come together quickly yet he remains as endlessly curious and enthusiastic as Pollux, his canine vineyard companion.

During our first visit, Laurent and Pollux were hardly able to contain themselves, moving quickly through their vineyard and forest playground poking and sniffing, analyzing flowers and herbs and limestone rocks like they’d just discovered them. Laurent paused as we examined the curious six-inch porcelain plates on white limestone rock and he explained that below are highly porous terracotta amphoras beside newly planted vines to offer them micro-doses of water and temperature regulation needed to thread the needle through the hot and dry summers in their crucial years before fruit production and greater root development; these clever and cute pots are a useful gardening technique he saw in Japan that replaces drip irrigation. Some people use punctured plastic containers as well, but that’s neither sexy, cool, nor aesthetically pleasing in such a natural setting.

You can take the man out of the wine bar, but you can’t take the wine bar out of the man (or something like that). Laurent transformed from rustic wine grower to hospitable Parisian barman (which may seem like an oxymoron) the moment he held the cellar door for us to pass into his winemaking workshop. He described his objectives with each aging container while patiently watching and offering a light commentary to preserve the mystery for each of us to bond with his wine in our own way: to discover something completely new or uncannily familiar; to let our interpretations and creative juices flow; to make our relationship personal and deep in a matter of sips with our unique perceptions that only we sometimes understand. As Andrew Jefford writes in the opening sentence of Drinking with the Valkyries, “We know no moment quite like this.”

Childhood friend and business partner at Le Vent des Jours, François Sudreau is not only a great supporter of Laurent’s dream, he is also one of his biggest fans. With his infectious smile and eyes enlarged by his glasses, a bottle or glass in hand (and sometimes a cigarette in the other), like Laurent, he closely attends to his guests: Water? Wine? A smoke? Perhaps some rillette de canard? A great friend to have for any epicurean, François’ 130-year-old family business carries from the late-1800s to our century the ancient craft of charcuterie quack: confits, rillettes, pâtés, and foie gras a hundred ways. Sudreau-Côte Cave is an evil temptation in the center of Cahors that preys on those of us who lack restraint for France’s Michelin-starred picnic fair. His shop is lined with all their ancient recipes in jar and tin, and also a fabulous collection of wines, piles of the most mythological French cheeses and sausages (especially those from the southwest), along with a room in which to sit, pull corks, enjoy everything on offer, and commune. François brings a dangerously good accompaniment to visits at Le Vent des Jours, and he surely pushes harvest lunches and a quick casse-croûte to a stratospheric level.

Once a prolific variety used for its color and structure contribution to Bordeaux, a frost in 1956 exposed Malbec’s Achilles’ heel for this once rare seasonal challenge compared to the Cabernet brothers and Merlot. Commonly referred to as Cot (pronounced like the abbreviation for company: Co.) in other areas of France, its thick skins and dark, lip-and-mouth-staining color earned the name, Malbec, which Laurent explains in the local dialect of Cahors means “bad mouth.” (The Vin de Cahors website, vindecahors.fr says the name’s origin involves a dubiously named and seemingly shameless self-promoter, Mr. Malbeck.) A half-sibling of Merlot, among many other winding vinous relations, Cahors (presumably made with Cot/Malbec) was also an inspiration for the Roman poets, Horace and Virgil. I suppose this shouldn’t surprise us that Horace wrote about it given that he was from modern-day Basilicata’s Venosa (in his time it was called Venusia and part of Apuglia), a central hub for Aglianico wines of Vulture. Assuming the Cahors of his time was Malbec, this grape is of an equally dark color and structure as Aglianico, though perhaps a little less intense by comparison when measuring tannins and perhaps naturally juicier and more seductive.

In Bordeaux, Malbec was used as a blending component to beef up Merlot and Cabernet Sauvignon. But in Cahors, Malbec performs on a world-class level as a single-varietal terroir wine at higher altitudes on limestone bedrock and calcareous topsoil. Perhaps more so than the low-lying and largely alluvial soils of Bordeaux, also similar to the many vineyards inside the Lot River gorge on former flood plains, the limestone roche mare of Cahors seems to naturally impart a more linear and strict architecture to the aromatic and palate textures to this often fruit-heavy wine.

An hour and a half northwest of Toulouse, three hours by car from the city center of Bordeaux, four hours from Lyon, five from Marseille, and eighteen hours by car, or 400 hours by foot from Horace’s hometown, one doesn’t “happen” to cross Cahors by car on the way to somewhere else. (Imagine how sound the Cahors must have been to travel so far over 2000 years ago and still inspire Horace to immortalize it!)

Located just west of the western end of France’s Massif Central, an ancient igneous and metamorphic rock mountain range with some young-ish, seemingly (hopefully) dead volcanoes, Cahors is a land of Jurassic limestone plateaus (referred to in French as causse) above a deeply carved, Mosel-like, dizzying meander of the Lot River. The Lot sprung near the Massif Central’s Cévennes and carried a variety of different rock types from the ancient massif to the Lot River Valley, depositing them in cobble form along the limestone ridges and eventually joining the Garonne River after 485 kilometers of travel from its source.

Malbec is perfectly situated in Cahors for many reasons. The most influential factor in determining a grape’s ideal place in the world is the climate. The southwest is generally mild in the winter, wet in the spring, hot in the summer, and humid in the fall. It’s more influenced by oceanic conditions despite being relatively equidistant from the Atlantic and Mediterranean. At the western base of the Massif Central’s Parc Naturel Régional des Causses du Quercy, Lot’s path has a convergence of strong opposing natural forces. The Pyrenees to the south block much of the intense African and Mediterranean heat and spring storms, and, like the Massif Central to the east and north, offer cool mountain air relief; the Massif’s north winds also bring Cahors’ biggest threat of frost. Toward the west, it’s open to the Atlantic, which brings autumnal rains and cool winds. With similarities to Southern France’s famously howling cold north wind, the Mistral, the opposing warm Autan winds originate above the Sahara and roar through the Languedoc and Roussillon gap between the Massif Central and the Pyrenees, through Carcassonne, Toulouse and finally Cahors, and it can be beneficial or dangerous, depending on its duration and timing. Laurent says that it often carries a lot of desert sand, and, like the Mistral, it’s said that it usually lasts for three, six or nine days. If it arrives late in the growing season, it can dry grapes and reduce yields, as it did in 2023. However, Laurent’s biggest concern among these multidimensional influences is hail.

The vines have been under biodynamic culture now for almost two decades. The conversion began with Fabien Jouves (Mas del Périé), a biodynamic-natural wine vigneron who sold the vines to Laurent and François in 2017. What great fortune to walk into such a thriving ecosystem!

The following is a lightly edited version of Laurent’s responses to some of our questions, though it should be noted that he speaks English well.

My agricultural philosophy as a neo-winemaker is as simple as possible. First, the size of the estate is a human scale: eight hectares of vines to make our living, eleven are made up of woods and pastures for our horses, eight for the sheep, one for the truffle oaks, and one with woods for our beehives.

I try to apply a “farmer’s” common sense and replace most Phyto treatments with infusions, porridges, and natural minerals. If my schedule allows it, I follow the planet’s calendar; if I can’t, I deal with those processes the following days. Our animals eat organic hay and graze on organic lands, so they make organic manure which we recover to make our supply of organic elements for our soil health. Our horses also pull our plows and our sheep are part-time mowers and fertilizers. Our bees make honey for our breakfast and to treat our horses’ wounds. White clay is also used to heal the wounds of animals or ours, but we also spray it on the vines as a way of using a natural substance to fight against leafhoppers effectively. All these natural products cost almost nothing, unlike Bayer or Monsanto products which are accompanied by very harmful effects.

Since 2022 we leave the grass cover [which is extremely spare anyway] in the center of the vine rows and till only directly under the vine lines in autumn to build a mound around the vines for winter protection. At the beginning of spring, we put the mound back.

Ultimately, Laurent’s philosophy is to first respect nature and work in its flow as fluidly as possible when creating their wines. The second is to make sure his wines bring clear sensations related to this historic vineyard land and most importantly to the rocky and fully exposed terroir.

“Aside from an empty bottle, the greatest compliment is to taste my wine blind and tell me it’s Malbec on limestone.”-Laurent Marre

On their thirty hectares, just southwest of Cahors’ town center and east of the village, Villesèque, Laurent and François have a single, contiguous, eight-hectare vineyard plot on a limestone plateau. “Maintained with love,” the bordering forests on the north and east offer some frost protection, and the 284-310 meters of altitude (higher compared to neighboring appellations, Bergerac and Gaillac) brings good air circulation that reduces fungus populations resulting in fewer vineyard treatments during the vegetative cycle. Laurent explains that the seasonal average of sulfur and copper treatments is around six to seven times, though in the hot 2022, there were only three, and in the dismal 2023 there were 13, though they still lost 60% of their crop.

The summer’s diurnal shift when perched up on the causse plateaus is dramatic. The days often hit highs between 36-42°C and then at night plunge to 16-22°C, with the wind always present. The white limestone also keeps the ground cooler in this fully exposed setting, which pushes harvest times (during the last decade) of Malbec to late September and sometimes into early October.

Even if it’s a small piece of land, Laurent explains that there are three distinct geological settings. The differences are most evident with Malbec picked over 10-12 days with the first grapes harvested where the central plot thickens with red clay (Quaternary geological age), followed by the red-tinted Jurassic limestone section at the bottom, and the last of the Malbec is picked from the white Jurassic limestone sections in the upper part of the vineyard where the sheep hang out the most. The Jurassic age of the limestones is dated to the Kimmeridgian (Upper Jurassic). Though they’re more similar than different from the famous sharp but friable and soft Kimmerdigian marls of Chablis and the Upper Loire Valley, they’re hundreds of kilometers away and are not exactly the same.

Much of the limestone formations have heavy faulting that allows roots opportunities to dig deep. On the top areas of the causse with what seems like impenetrable limestone, the rock is broken up over time from cryofracturing (among many other names with perhaps the most common reference, the freeze-thaw cycle) where water enters gaps in rock and freezes and expands, wedging the rock apart. No known hard rock can resist the 10-11% expansion when water turns to ice, but uniquely, the softer the rock the less it is affected by freezing water; for example, because of the plasticity of mudstones and claystones, they’re not affected.

Malbec is the focus of the domaine and the vine age ranges between 25 to 45 years old (2023). It’s planted with 5000 vines per hectare, which is half of what is typical in the Côte d’Or. It grows on all the soil types, but principally on the rockier limestone sections. The 40-year-old Merlot vines are planted on the heaviest red clay. The 25-year-old Gros Manseng and Ugni Blanc (10% of the C’Juste blend) are on the Quaternay section (red clay) as well but with a large vein of white clay. Chardonnay and Viognier are also inherited and were planted 25 years ago on the poorest limestone soils.

As a former sommelier who’s had every French wine at his fingertips, it’s understandable that Laurent is not completely satisfied growing what was already planted. This prompted him to cultivate other varieties he loves that thrive perfectly on limestone and clay; they’re also varieties that we love: Chenin Blanc, Pinot Noir, Trousseau, and Syrah.

With 90% of C’Juste composed of Gros Manseng grown on the large veins of white clay in warm-to-hot summer conditions and without added sulfites, we may expect its takeoff to be like the first throttle on the tarmac in a fast but chubby commercial liner; however, it’s more like (what I imagine) being pressed against the seat of screaming fighter jet during takeoff. We, for one, find C’Juste yet another impressive no-sulfites-added white wine that demonstrates what’s possible if done correctly in the cellar. It’s as inviting as it is electric, and once open the bottle tends to empty rather quickly.

Laurent describes C’Juste as, “a rich wine due to the typicity of Gros Manseng. From one year to the next, the Victoria pineapple side (a note not often found in colder and wetter climate Gros Manseng wines) remains the common thread, while the 10% of Ugni Blanc brings freshness and acidity—the lemon side on the finish. It’s for the meal rather than apero hour and can compete with a fine Chardonnay in terms of power and the freshness of a great Chenin Blanc.”

Once in the cellar, the grapes are first left for 24 hours in concrete to cool down, then they’re whole-cluster pressed before being returned to the same medium. At the end of the 10-15-day natural fermentation, the wine is racked off the gross lees into four 8hl Italian terracotta amphoras for 11 months before bottling. There is no sulfite added to this wine at any time, though the exception is the 2020 version. C’Juste is lightly filtered but not fined.

The red starter in Laurent’s range is also the wildest of his no-sulfite-added Cahors. It’s not made every year but reserved for years (like 2018, 2021, and 2023) where certain lots don’t hit the stylistic mark for the Les Calades and Les Moutons bottlings.

Initially, the wine is explosive, shooting aromas in all directions. A member of our talented team at The Source, Tyler Kavanaugh, tasted the 2021 over five days after the wines arrived stateside and sent notes that perfectly sum up this wine: “It’s wild and swerving out of the gates; lots of raw and pungent primary fermentation elements raging around; a little awkward at first.” On the second day open after only a little taste on the first, he describes it as though the angst backed off and the wine is more subdued and approachable, though still sanguine and raw. On day five he pulled it from his refrigerator, “And wow, what a remarkably stable and intriguing wine without SO2. It softened into this delicate, powdery wine; the acidity and volatile elements zenned out; nothing weird, out of place, or fault-adjacent to be found. Much of the raw and unhinged qualities are no more. It’s honestly become a geeky pleasure to drink to the point I may very well polish the bottle.” Other pronounced notes include high-toned purple fruits, purple flowers (iris, hibiscus, petunia), beets (fresh and roasted), freshly tilled soil, dark and earthen; smells of a nursery/gardening store; Sichuan pepper and Chinese five spice.

“Un Jour ou l’Autre must be my everyday, financially accessible Cahors; a 100% Malbec for thirst, aperitif, sausage, barbeque.” -Laurent

Because it comes from the plots used for Les Moutons or Les Calades, it’s composed of a combination of Upper Jurassic limestone bedrock and the Quaternary white clay and limestone rock topsoil. (For more on the terroir read “The Plot” and “On the Range” sections.) Once in the cellar, the grapes are 80-90% destemmed before a 20-30-day natural fermentation in open concrete vats. Two pump-overs a day are employed early in the maceration period and almost nothing is done during fermentation. It’s aged in 50hl concrete tanks for seven months before bottling with a light filtration. No sulfites are added.

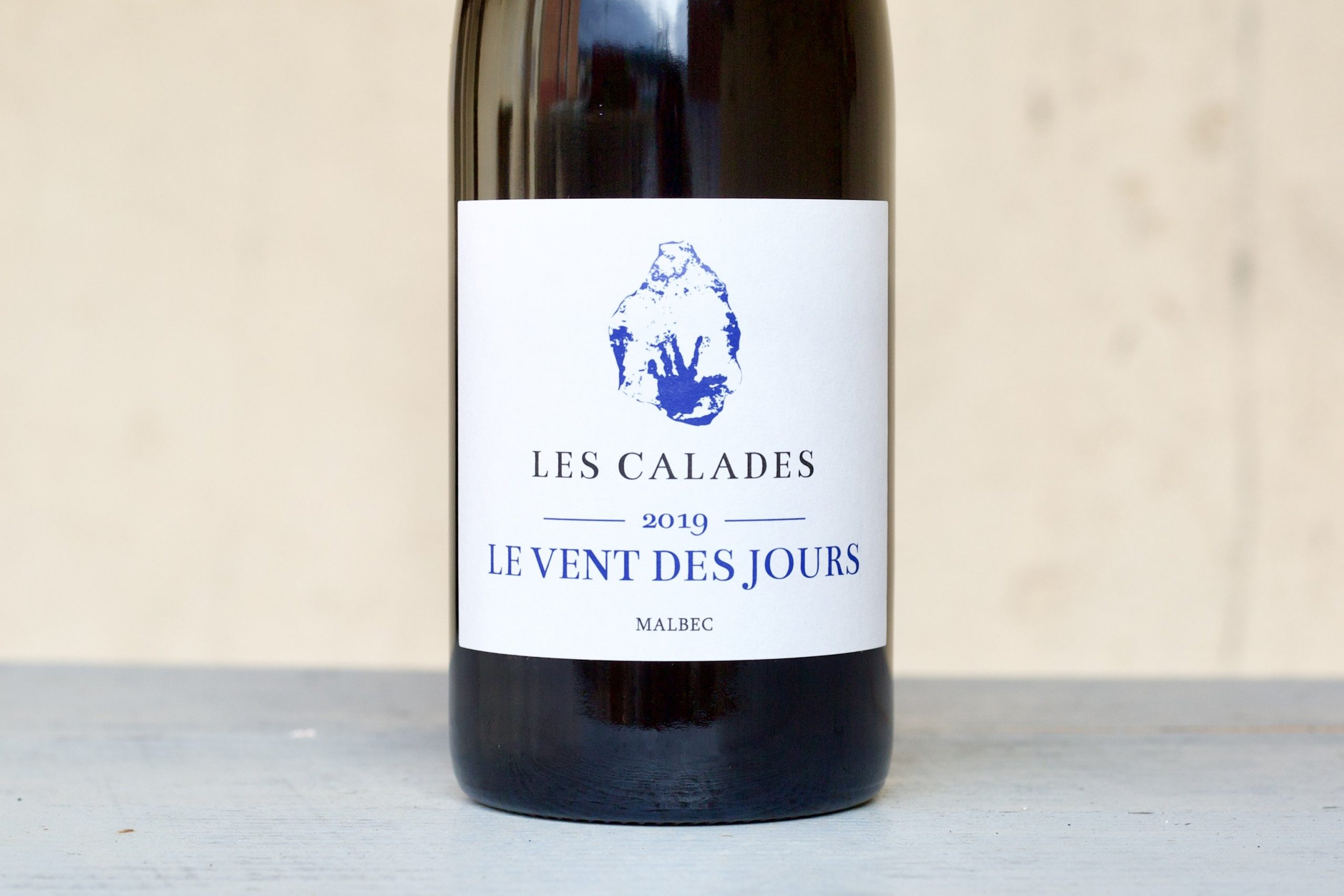

A blend of Malbec from their three different soil types (see The Plot section) picked at different times within a 10 to 12-day span, it is for this that Laurent’s mid-range Cahors, Les Calades, is the most accessible and widely appealing. He describes it as the flagship of their range, “a pure Malbec with power and freshness that represents the king grape variety of our appellation on limestone, and the new generation of Cahors: more fluid, rich and balanced with a distinct and very present mineral and marine finish.”

Each plot has an average age of around 40 years (2023) and naturally ferments in separate concrete vats with 10% of whole bunches between three weeks to a month. Because Malbec already provides a lot of substance from its very thick skin, he does a single short pump-over every two days to preserve the hygiene of the cap of about 300 liters in total of the 50hl vat. After fermentation, the grapes are pressed and mixed with the free-run wine and aged for 11-13 months equally between Italian terracotta amphora, old 30hl French oak vats and six-year-old 225l French oak barrels. They’re lightly filtered at bottling without any added sulfites.

Again, we defer to Tyler Kavanaugh for a thorough description of the 2020 Les Calades tasted around Thanksgiving: “A deep and focused black-red fruit medley and purple flowers with a refreshing graphite-cool mouthfeel. It’s soft and broad in the mouth and a little sanguine in a steely, iodine-forward sense. The tannins are pleasantly chewy with sweeter black and red berries (though not ripe/overripe) and loads of freshness. It feels firm in the middle on weight, structure and acidity with a nicely detailed direction to the fruit that keeps you coming back to the tart blackberry and boysenberry, bramble, florist fridge fresh dark flowers and leaves and stems in the cold. It’s solid on the second day with the floral aromatics lifting well above the fruit with the tannins lightly tightening up. It didn’t last beyond the second day due to its deliciousness factor, which kept me pulling it from my ‘secret’ Thanksgiving bag.”

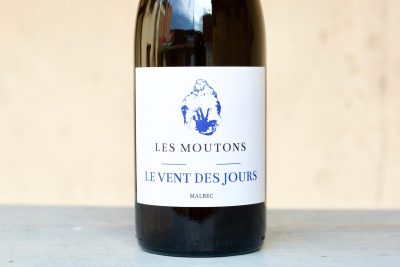

Les Moutons comes from Laurent’s favorite Malbec plot at the top of the hill on its poorest rocky topsoil on Jurassic limestone bedrock. This is where les moutons (the sheep) like to hang out the most, eating and fertilizing—“a sort of organic doping of the vineyards,” Laurent says.

“Les Moutons is destined to be my grand cuvée,” Laurent says

This 0.45ha upper plot in the vineyard always produces extraordinary wine from its 45-year-old vines, which he partially attributes to the plot’s spare soils and the regularity of sheep contributions. But perhaps the most significant factor is that it’s not made every year. Laurent’s vision for this wine is to have something serious and precise, and when the year doesn’t line up the way he wants it to, like 2021 and 2023, he blends it into Les Calades. Tyler’s take on the wine was that it has “a more finely etched and detailed frame with dustier but more precise tannins; it’s more elegant and less fruit nuanced than Les Calades.” This fineness and savory character is not only by design from Laurent but also by the forceful voice of this section of his vineyard.

Once the grapes arrive, half are destemmed and layered, “millefeuille style,” with the whole bunch clusters in a 30hl tronconic wood vat for around three weeks of natural fermentation with a control of between 12-14°C. The must is pumped over once per day until pressing.

Despite the notable beauty and class of the wine each year that it’s made, Laurent says that he’s still finding his way to fully realize his vision for this wine. In 2019, it was aged for 13 months in equal parts amphora, foudre and barrel. All of the 2020 was aged in 8hl Italian terracotta amphoras, and in 2022 it was four-year-old French oak barrels (at least from October 2022 to October 2023). As with the other reds, Les Moutons is not fined but passes through a light filtration, and has no added sulfites at any time.

Each season is quite different and despite the notably erratic behavior today, it’s wild every year regardless of climate change. The most notable challenge today is how the extremes are even more extreme. Laurent has provided a quick overview of his most recent vintages.

2019 was very sunny which resulted in a lot of sugar which, of course, raises the alcohol. The natural yield was 32hl/ha.

2020 was a perfect vintage that resulted in magnificent Malbecs. 2020 was the first season they used pheromones to confuse the grape worms during their reproductive period. Laurent describes this as a smashing success. There was almost no rot in the vineyards and the yield was 36hl/ha.

Laurent refers to 2021 as a “shitty year!” with nine months of rain over 18 months. “Luckily it was cold, so we didn’t have mildew problems.” It was difficult to have the sugar levels they wanted and also difficult to harvest with showers every day. The final yield was an average of 23hl/ha. Regardless of the growing season, the 2021 C’Juste is spectacular!

2022 was a very beautiful vintage, similar to 2020 but with four months of drought from May to August and temperatures between 36 and 42°C. However, there was little water stress thanks to the depth of the old vines’ roots. The yield was 38hl/ha.

2023 was a very complicated year because of a lot of rain in spring with 220mm (almost nine inches) in three days at the beginning of June and storms every evening in May. The spring and summer were very hot and there was a permanent attack of mildew, very similar to what happened in many other European wine regions. At the beginning of September, the hot Autan wind dried many of the remaining grapes. Many winegrowers didn’t even harvest. The average yield was 12hl/ha.