Alexandre Déramé

This website contains no AI-generated text or images.

All writing and photography are original works by Ted Vance.

Short Summary

After six years of enology school in Nantes, the humble Alexandre Déramé took over his family estate winery. Although his total production is medium-sized, his yields are among the lowest in Muscadet; his Vieille Vignes yields are minuscule. Though toyed with in the vineyards for many years prior, organic conversion began in 2023 with the objective of having the entirety certified within five years. Located in the gently rolling hills of Mouzillon, Morandière is a tiny commune one of the most highly regarded wine villages in Muscadet. Mouzillon is distinctive for its soils high in concentration of gabbro (a metallic-flecked, pale green and black, hard igneous rock developed through slow cooling of basaltic magma) with loamy soil of orange-colored silex and quartz-like rocks. This unique rock imparts the wines with tremendous power and tension.Full Length Story

During my first visit to Clos des Roches Gaudinières, Michel Chiron, the gruff and crusty retired vigneron that sold the plot to Alexandre Derame, said with a hoarse voice and an icy stare: “Les Roches Gaudinières is one of the greatest vineyards in France! It’s the La Tâche of Muscadet!

Finding Alexandre

Domaine de la Morandière represents the only producer we’ve ever procured from a big tasting event. We try to avoid these kinds of cattle calls because we get too overwhelmed by that many wines and it’s hard to taste in front of the complete stranger who made it. I feel obliged to be politely dishonest if I don’t like the wine and I don’t like to do that in general, but I especially don’t when it comes to wine. Another thing is I’m a terrible liar; my eyes reveal my true feelings in a split second. It’s easy to go around tasting wines with no intent other than doing just that, and to find a true diamond in the rough is exceedingly rare. The truth is that the best ones are most often found through contacts, sources, not in a herd.

Alexandre was among somewhere between thirty to forty growers with dozens of different Muscadets on each of their tables. He stood out as clear as day when my business partner, Donny Sullivan, and I tasted his wines first and then doubled back after every single other Muscadet in the entire place failed to beat it. He had nice labels, too. Perhaps Alexandre’s style wasn’t what we had in mind initially—we were in search of a slightly more ethereal, easy to drink, minerally type—but his wine did match our general stylistic preferences: high energy, dense core, serious. It was a lucky strike and the second to last stab I ever took at a tasting event. (The last event I attended was a “natural wine” fair called La Dive Bouteille, held in Arles, France. I was accompanied by Brian McClintic, formerly known as Brian McClintic, MS. There were numerous wines that made both of us nearly regurgitate, and I’m not exaggerating. That was the last one for me. Ciao.) Of course, Domaine de la Morandière has been a great success for us, but even more, we’re happy to work with the humble and enthusiastic vigneron behind them. Alexandre is cautious and gentle, but it’s fun to take in his enthusiasm when speaking of his wines because he gives the distinct impression of being an explosive on the verge of being lit.

I guess that every great wine in the world has some shade of La Tâche inside, and in every La Tâche, there must be a shade of every other great wine in the world too.

Alexandre took over his family’s estate in the last years of the 1990s, after six years of viticulture and enology school, with a lot of competitive club soccer during his free time. Immediately he wanted to expand beyond his familial vineyards at Domaine du Moulin and so began the search for his own place. During the dig, he came across an interesting vineyard for sale with an illustrious vinous history. Clos des Roches Gaudinières caught his attention, just as he caught ours.

Cellar Notes

Given that Alexandre only makes white wines, it is pretty simple. A few important notes are that everything is whole-cluster pressed by pneumatic press, settled overnight and racked off the initial sediments, naturally fermented in stainless steel tanks, and aged in either stainless steel or porcelain-lined concrete vats. Sulfur additions are made only after primary fermentation (a helpful approach for greater longevity and lower overall sulfur doses) has been completed under cooler temperatures, and no malolactic fermentation happens, which is mostly inhibited thanks to the pH of the wines, which usually hovers around 2.80, making for a very inhibitive environment for malic bacteria. To safeguard against the off chance of any potential malolactic fermentation action in bottle, the wines are filtered with a diatomaceous earth (skeletons of microscopic plankton), which he prefers over other filtration systems due to the gentler handling of the wine—a filtration system commonly used in German and Austrian Rieslings.

The Vineyards

Comparisons to La Tâche are overused daily. They’re a great pitch when selling wine to those who don’t have much experience drinking La Tâche, but it’s almost impossible—not saying it is impossible—to measure up. In fact, comparisons to La Tâche may stand atop the most far-fetched and absurdly overindulgent name drops to sell a wine that doesn’t have La Tâche directly on the label itself. This is obviously the case with Chiron and his comment about Clos des Roches Gaudinières (C.R.G. has a nice, familiar ring to it…) being the La Tâche of Muscadet, but after many years tasting this wine, I think I may understand the comparison to some extent only because of the near indestructibility it has while maintaining an extremely dense core and deep mineral characteristics. Like all the La Tâches out there, its sturdy stuff, and Alexandre insists that it requires a lot of time aging in the cellar and bottle before they display the full spread of their complexities—just like any great vin de garde. Perhaps this seemingly indestructible characteristic and the density of the wines is what the old salty vigneron meant by the comparison. I guess that every great wine in the world has some shade of La Tâche inside, and in every La Tâche, there must be a shade of every other great wine in the world too.

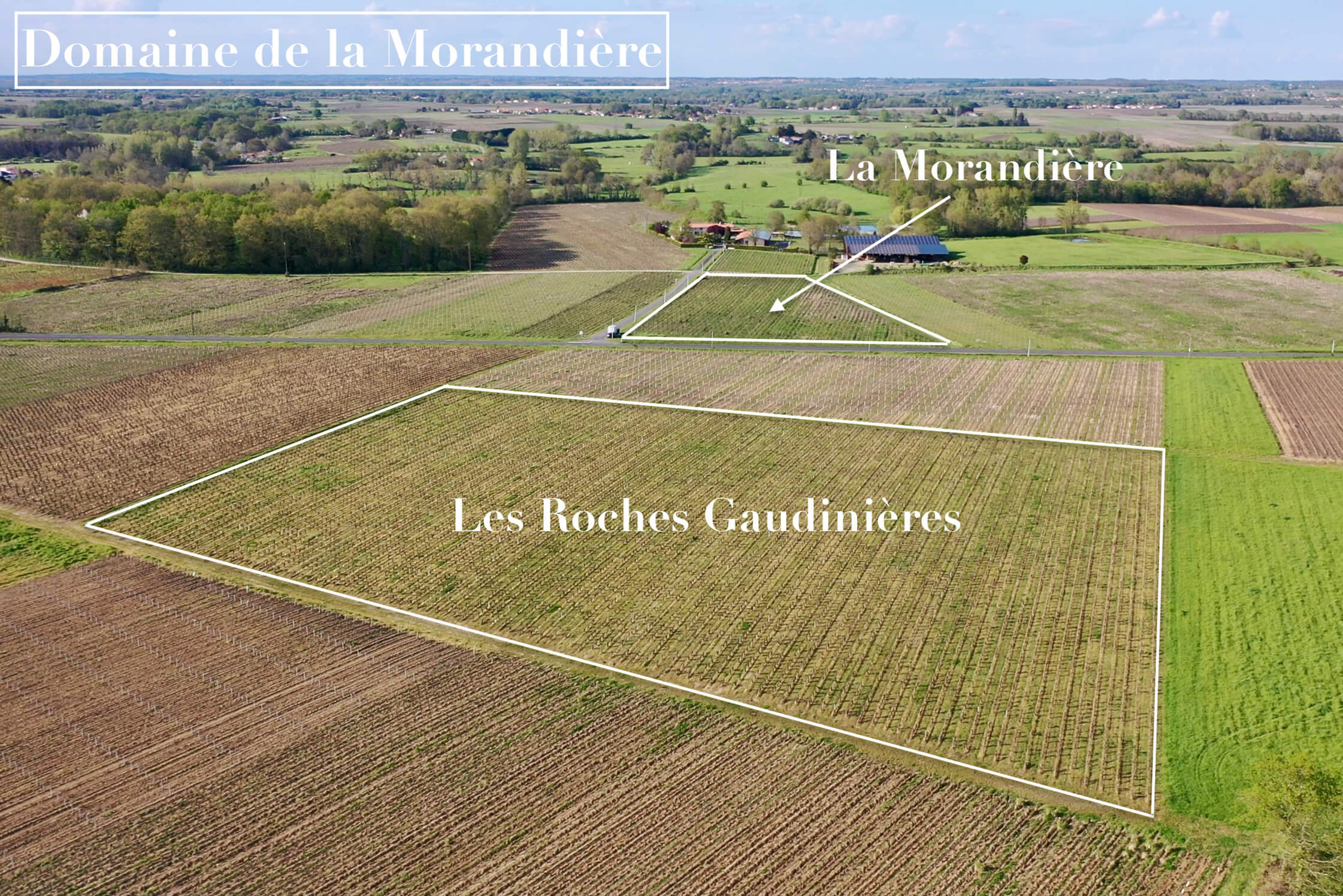

Derame’s three hectares in Clos des Roches Gaudinières (labeled under Les Roches Gaudinières Vieille Vignes), inside Mouzillon-Tillières, on the eastern side of Muscadet Sèvre et Maine, are grown on slightly acidic soils (~6.0 pH) of extremely hard bedrock composed of gabbro (a pale green and black intrusive igneous rock developed through slow cooling of basaltic magma under the earth’s surface), and a clay-rich topsoil with a lot of loose gabbro rock and an average of eighty centimeters topsoil depth. The vines are a mix of massale selections and old biotypes with three-quarters from 80-year-old vines and the rest being fifty years old. This magnesium and iron-rich rock, the clay-rich and rocky topsoil and the old vines and their extremely low natural yields of 25-30hl/ha at most in any given year (less than half the production of his other vineyards; for the sake of context, it’s about two tons of fruit per acre, which is about the same as Châteauneuf-du-Pape, the French appellation with the lowest AOC regulations for yield) imparts a dense power to its wines, obliging extensive aging before being enjoyable to drink. Alexandre ages it in tank for three to five years followed by at least two years in bottle before release. It has tremendous aging potential, demonstrated through many old vintages we’ve imported (starting with the 2002 vintage released ten years past its vintage date) and the surprising freshness it maintains after many years. Who knows what can be credited for its longevity, but there’s definitely something special happening.

Another wine in Alexandre’s range, Le Morandiére comes from vineyard land that’s not too far from C.R.G. and shares the same gabbro bedrock. However, the topsoil is different with its sandy/silty composition that goes about 80cm deep. The vineyard’s genetic material is a bit different here than in C.R.G., as it is in the Domaine du Moulin estate, which surely differentiates some of its characteristics. Alexandre noted that one obvious difference is that there is a lot less gabbro rock in the topsoil matrix. The vineyard renders extremely solid wines, and for the price it represents an extraordinary value with bigtime chops in the context of other Muscadets. Because of the lighter topsoil, it’s ready for enjoyment much earlier than the Les Roches Gaudinières bottling and is aged appropriately in the cellar for a shorter period and released just prior to the oncoming harvest of the next vintage.

Alexandre’s familial domaine, Domaine du Moulin (which we haven’t yet imported) located in Saint-Fiacre-sur-Maine, west of Mouzillon-Tillières and closer to Nantes, is grown mostly on fine-grained topsoil, somewhere between sand and silt. The topsoil is about thirty centimeters deep and derived from the underlying bedrock of granite and schist. The mildew pressure is less than Morandière’s other vineyards and is also less prone to frost—a new dilemma in this region in the modern age. Harvest usually takes place one week before their vineyards further east on the gabbro bedrock, these vines planted around thirty years ago (2021) to more productive biotypes and yield between 50-55hl/ha and make lighter, fresher wines that are simpler than those from Mouzillon-Tillières, and they are also easy to drink earlier in their evolution. It’s aged in tanks for six to eight months prior to release.

Organic Conversion

Under the oversight and help of other local organic growers, notably Jo Londron from Domaine de la Louveterie and Marc Olivier from Domaine de la Pépière, Alexandre has begun to move toward organic farming, starting in 2020 and all will under full conversion by 2024. However, some very basic—and understandable—challenges stand in the way of full conversion entirely at once. The biggest obstacle is to simply find enough good workers to help in the vineyards; once started on organic farming, one needs to be equipped to manage all the things nature stirs up that must be dealt with through more ecological means, which means more money and manpower.

At only sixty meters of altitude and only about fifty kilometers from the Atlantic and in the far north and west of France, the challenge of organic farming in the area is already daunting. Other challenges are that for many of the vineyards, particularly for Clos des Roches Gaudinières, with its massale selection vines that produce tight and tiny clusters with very thin-skinned grapes, coupled with the water-retentive clay soils and the high precipitation (around 30% more than Anjou, only one hour east by car), it’s a paradise for mildew pressure and the potential for disaster (which has been all too well-demonstrated in these last few vintages along the Atlantic coast of Europe) is extremely high. Who can blame him for exercising great caution, especially since the pricing of the wines compared to other more famous wine regions is extremely low, while the costs of production are quite comparable.

One of Alexandre’s answers to meet the challenge of the labor shortage is to simply reduce his vineyard holdings. He has sold off ten of his thirty-nine hectares in recent years and plans to reduce further to somewhere between twenty and twenty-five. Once at that level, all will be converted to organic culture. This marks a first for me: a young vigneron (born in 1979) who has willingly sold off vineyards in pursuit of increasing the quality of his wines over volume of production; most growers never let vineyards go once they have them, unless they don’t have heirs. It’s true that past a certain point, quality with real personality and the attention to detail to create something truly fine is hard to maintain. His move in selling vineyards is commendable, and for us, a strong indicator of his commitment to quality.