Vincent Bergeron

This website contains no AI-generated text or images.

All writing and photography are original works by Ted Vance.

Short Summary

On the rolling hills and floodplains of the Loire River’s Montlouis-sur-Loire, the humble and gentle Vincent crafts his finely tuned certified organic Chenin Blanc (still and sparkling) and Pinot Noir wines from 3.4ha of vineyards grown on limestone bedrock, perruches (fossils, lithified clay, flint/silex), sandstone, clay, and limestone rock topsoil. These “natural” wines are spontaneously fermented and aged in French oak barrels (some in fiberglass)—most without any addition of sulfites. With his concession to nature and commitment to honor the season, sans maquillage, sin compromise, he sets his wines on a direct course, showcasing each season’s gifts and challenges, allowing his wines to freely express the mark of their birth year. Warm vintages (like 2020) taste of a season’s richer fruits and softer palate while still being delicate and complex. Cold years (like 2021) are brighter, fresher, and more tense.Full Length Story

Timid and cautious yet gently charismatic, middle-aged (born in ‘78) but youthful and spirited, with a heart of gold and a deft touch with his craft, the gracious Vincent Bergeron discovered his calling to the vigneron life while walking the streets for La Poste, trading in antiquities, and periodically working construction. These were simple trades, though perfect for young ponderers like Vincent, at least for the moment.

He received degrees in Art History, Literature, and Agriculture, had many different work experiences that were capped by the viticultural mentorship of Jean-Daniel Kloeckle, Hervé Villemade, and Frantz Saumon. The latter gifted him with a tractor, a small Pinot Noir vineyard and part-time cellar job, and Vincent commercialized his first wine in 2016 (though he’d tinkered with various bottlings since 2013)—500 bottles of bubbles that all went to a Japanese importer. When he talks about his project, he always starts with his great appreciation for Frantz’s generosity, for giving him such a jumpstart.

He and I were introduced by Montlouis-sur-Loire local, Gauthier Mazet, also a new vigneron (practicing since 2020) and wine industry connector, who lives by the river in the epicenter of where Montlouis’ bloom of amazing producers are making deeply inspiring wines from an underdog appellation in miniscule quantities, most of whom sell almost everything to Japan and very little in France. This includes Vincent Bergeron, as well as two others who’ve also trusted us to be their US importing partner: Hervé Grenier, owner of Domaine de la Vallée Moray, a craftsman of densely mineral and emotional wines that embody the focus of a scientist maker in his second career as a vigneron, and Nicolas Renard, a forcefully independent and elusive natural wine wizard, a virtual ghost whose wines are nearly impossible to acquire, and who transcends style and mode with no-sulfur wines, both white and red, that are simply in their own stratosphere, easily holding court with the best examples of x-factor-filled, dense, moving whites in the world, and reds that captures the essence of the earth and human in a bottle.

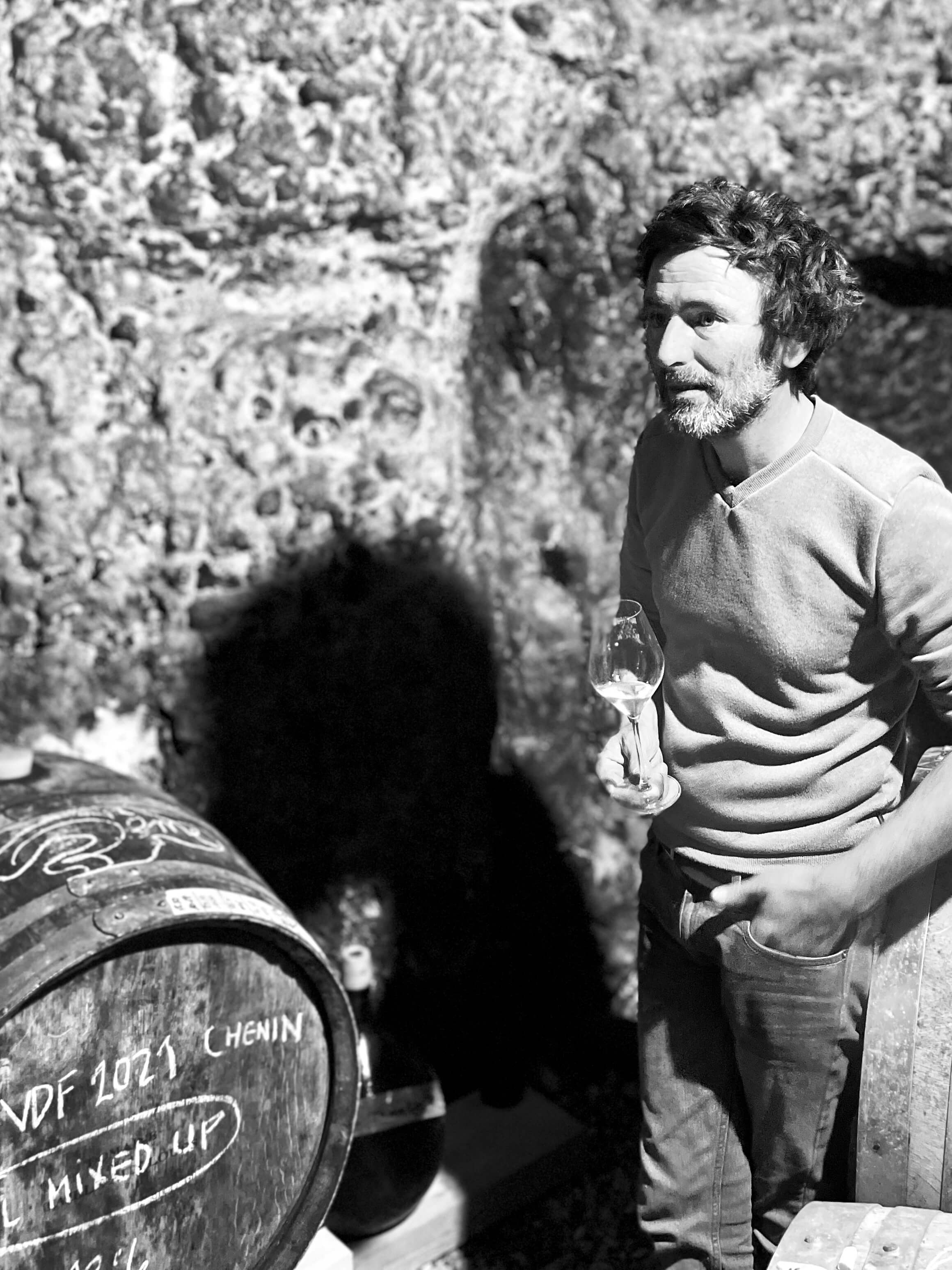

I first saw Vincent on a cool and sunny spring morning in one of his vineyard parcels close to downtown Montlouis. With his thick mane of lightly salted pepper flowing in every direction, he wore casual well-worn clothes stained by hard work, and he shied away from the camera as I stole a few shots before our official greeting. His hands are those of a true vigneron; they were dirty from the vines and caked with earth, swollen, strong from a life of labor, scratched, scraped, gouged and bloodied. He seemed a little self-conscious to be shaking my hand, and I instantly knew I’d like him: it was impossible not to.

Vincent is rare in today’s world of self-aggrandizing young vigneron talents—sometimes appointed by the wine community and often by the self, as “rock stars.” Many of them seek celebrity and membership in idealist tribes rather than going for truth and an honest view into this métier, this art, and above all, this craft, a marriage of homosapiens and nature. Vincent is a vigneron’s vigneron, a human’s human, an uncontrived example of how to live and simply let be, spiritually, without trying to be “someone.” He only tries in earnest to be himself—not for the world to see and celebrate, but for his family, his comrades, for himself and his humble yet idealistic relationship to wine and connection to nature. Though not an active provocateur, to simply be in his presence you might, like I do, contemplate life choices and motivations, what’s important to you, and why it’s important, and what the hell am I doing with my few short years on this planet. Without effort or intent, he enriches others with his homage to his environment, a spirituality and open self-reflection in casual settings, drinking wine outside on a cold and sunny day in front of a tiny, wobbly table packed with cheeses and cured meats, and oysters (also a favorite of his extremely young kids—only the French…), a perfect match for his bubbles and white wine. The talks are fresh and lively, more about life than wine, though in this context wine is life. His wines speak for themselves, and gently, as do his organic and biodynamic vineyards that are teeming with life. Sometimes he appears lost, even surrounded by his people, as he gazes into the world, into nothing, thinking, reflecting, wondering about his path. Perhaps he thinks less than it appears that he is, but it’s doubtful.

Emotionally piercing, Vincent’s mineral-spring, salty-tear, petrichor Chenin wines flutter and revitalize; a baptism of stardust in his bubbles and stills—a little Bowie, a lot of Bach. His Pinot Noir is earthen en bouche, and aromatically atmospheric, bursting with a fire of bright, forest-foraged berries and wild flowers, and cool, savory herbs rarely found in today’s often overworked, oak-soaked, and now sun-punished Pinot Noirs, the wines that were the heroes of the past millennium, but today are a flower wilting under the relentless sun. Advances in the spiritual heartland of Pinot Noir have been made, though I sure miss the flavors of the Côte d’Or from my earlier years among wine.

Vintage is important with Vincent’s wines. With his concession to nature and commitment to honor the season, sans maquillage, ni compromise, he sets his wines on a direct course, showcasing each season’s gifts and its challenges, allowing his wines to freely express the mark of their birth year. Warm vintages (2020) taste of a season’s richer fruits and softer palate while still being delicate and complex. Cold years (2021) are brighter, fresher, more tense and rapier sharp with a gentle and welcome stab.

The Vineyards

On the east side of the fabulous but small and modern Loire city, Tours, across the Loire River from the historic splendor of Vouvray on a series of undulating hills with some dramatic slopes mixed with mellower hilltops, sits Montlouis. It’s a long stretch of vineyards between the rivers Loire and Cher to the south, on floodplains shaped by torrential flows over the eons.

Vincent explains that between Vouvray and Montlouis there have always been differences in soil structure, topography, and social hierarchy. While Vouvray maintains a more celebrated vinous history (as illustrated by the bougie houses across the river, so different from Montlouis’ more rural and less ornate neighborhoods), some of its historical relevance seems to stifle creativity and growth—as happens so frequently in many historically celebrated regions in the wine world. Why change what already works well? Historic families often prefer to preserve their position instead of rocking the boat of a viticultural system that, after many generations in place, continues to provide wealth for those next in line.

In contrast to Vouvray, Montlouis-sur-Loire is filled with young and finely aged winegrowers with more open minds and a strong desire and capacity for kinship and the sharing of ideas. Many had widely varied experiences prior to choosing the vigneron life and together they’ve created a tribal environment where they help each other to push that rock further up the hill. Organics have become a way of life for many in this circle and the influence of this free-thinking community is expanding. Montlouis is exciting and there are so many talents emerging from this extremely praise-worthy appellation that’s up to now been an underdog. Always the bridesmaid and never the bride? No longer. Some earlier trailblazers opened the path, the most famous, perhaps Jacky Blot and François Chidaine, and others more quietly developing their names and furthering the reputation of the appellation, like Frantz Saumon, Thomas Lagelle, Julien Prevel, Ludovic Chansson and Hervé Grenier, all of whom Vincent admires and calls friends.

Montlouis is written in every wine book to be sandier in general than Vouvray, which is true, though there is often great depth of clay further below the surface (lighter than on average than Vouvray), in the topsoil before the roots intersect with the famous whitish/yellow limestone bedrock of much of the Loire Valley’s best Chenin Blanc areas, and a slew of other elemental contributors have a say in the wine’s subtleties. Vincent has various plots in a few different zones of Montlouis, close to the bluffs that overlook the Loire River and others further away and closer to the Cher, both on classic limestone bedrock, with variations of perruche (fossils, lithified clay, flint/silex), sandstone, clay, and limestone. These structures are not independent of others but rather form a conglomeration and vary from one to the next and within the plots as well. To see the diversity, go to eterroir-techniloire.com

Though the land was already worked organically prior to Vincent’s last fifteen years of ownership, it was certified as such in 2018, and biodynamic principles are followed in the season’s life cycle, though they’re not followed closely in the cellar. Plowing is done mostly by horse every third year, or by Egretier plow, a fitting pulled by tractor. The harvest begins with alcoholic and phenolic maturity in line with the chemistry of the grapes—pH, TA—and of course, the taste of the grapes. Pinot Noir is the first to be picked, followed by Chenin Blanc for sparkling, then the still Chenin.

The Wines

Vincent’s bubbles, Certains l’aiment Sec “Vin de France,” is gloriously ethereal and fun to drink. Like all his wines, the vintage has a big voice in the overall expression, but the spirit is the same: serious but playful and easy to gulp down. It’s made with a simple method using early pickings from the Chenin Blanc parcels. (Here, in this part of the Loire Valley’s Chenin Blanc region, many growers make numerous picks on their vineyards rather than just the one—a smart and utilitarian method to maximize quality with what yield nature provides, without being too forced.) Spontaneous fermentation takes place in fiberglass vats. Following malolactic fermentation, the wines are hit with their first sulfite addition of 20mg/L for its eighteen-month bottle aging. No fining, no filtration, no dosage.

“Morning, Noon and Night,” is about right for this exquisite, fine, platinum-hued wine labeled Matin Midi et Soir – Chenin Blanc “Vin de France.” This is Vincent’s inspiring still white wine, (especially the 2021), where the vintage seems tailored for his style: helium-lifted, minerally charged, cold, wet rock and taut yet delicate white fruit. All the elements from each vineyard parcel in his 3.4-hectare stable of 40-plus year-old massale selections (and .60ha of clonal selections) give it breadth and complexity while maintaining Vincent’s head-in-the-clouds Chenin Blanc. It’s hard to pick a favorite in the lineup, but this low sulfite dose Chenin (30mg/L) raised twelve months in oak barrels (with some new to replace older barrels, though not noticeable) is truly singular for this variety in the Loire Valley, so much so that it doesn’t even seem to be of this earth, but rather plucked from the heavens, angelic, virgin, pure, untainted.

The first taste of Pinot Noir out of the barrel, Un Rouge Chez Les Blancs, was jaw-dropping, a burlesque walk from glass to nose and mouth. In recent years, I’ve terribly missed Pinot Noirs that carry this grape’s nobility and naturally bright, energetic, straight flush (hearts and diamonds) of red fruits and healthy forest with wet underbrush. I was tempted to be impolite and drink down my entire barrel sample from this mere one acre of vines (0.4ha) instead of returning it (2021 vintage) to whence it came. I could’ve nursed that first 500-liter barrel to completion—I greedily wanted it all. By the end of my first visit, I wanted everything in his cellar just so my friends back home could bear witness to it. Given to him—yes, given—by Frantz Saumon, the land was organically farmed long before Vincent took the reins of the plow horse. Optimal for this young vinous artist to explore his direction with epic, terroir-precise and living fruit, he nailed it. It’s true Pinot Noir perfection: egoless, a balance of nature and nurture, sensual, honest, captivating, pristine, delicious. There’s no sulfite added to this wine, so the future of each bottle will be in the hands of the handler, though with its naturally low pH, high acidity, and low alcohol, and, most importantly, its balance, it should manage well over time. One pump-over per day in the beginning, two later on in the fermentation, a year aged in 75% old oak barrel, 25% fiberglass tank, it’s not fine nor filtered.