Domaine Rousset

This website contains no AI-generated text or images.

All writing and photography are original works by Ted Vance.

Short Summary

Stéphane Rousset’s vineyards are in Crozes-Hermitage’s northern communes of Erôme, Gervans and Crozes-Hermitage, including the legendary Les Picaudières. The hill structures and soil types differ significantly throughout the appellation with various exposures on moderate to very steep rock terraces. Rousset’s Marsanne grows mostly on loess topsoil and granite bedrock. The Crozes-Hermitage red wine terroirs are largely on granite with some variations of igneous and metamorphic rock. Across the river, in Tournon, two adjacent blocks of St. Joseph grow on extremely steep granite slopes. Whites are whole cluster pressed, fermented in concrete, mostly aged in steel without malolactic with remaining in oak. The reds are partial stem inclusion and are fermented in steel and then racked to barrel or tank where they age for about a year.Full Length Story

A gentle, jovial, quiet, and extremely humble man, Stéphane Rousset remains a relatively unknown gem in the Northern Rhône. His wines are built on solid craftsmanship and a clear muting of his voice in deference to those of his terroirs. He makes fabulous Saint-Joseph wines, and his wonderful Crozes-Hermitage selections put a rare face on this lesser-understood and appreciated appellation. The glory of the Northern Rhône Valley rests on Côte-Rôtie, Hermitage and Cornas, and while Saint-Joseph can give them a run for their money, Crozes-Hermitage suffers from its sheer size and ability to produce a great volume of wine from nearly every hectare, which ends up diluting how the appellation is perceived. However, there are some Crozes-Hermitage areas and vineyards that standout among the Crozes crowd—vineyards that share the same geological heritage as some of the aforementioned greats. Those special and overlooked areas are home to this story’s protagonist, Stéphane Rousset.

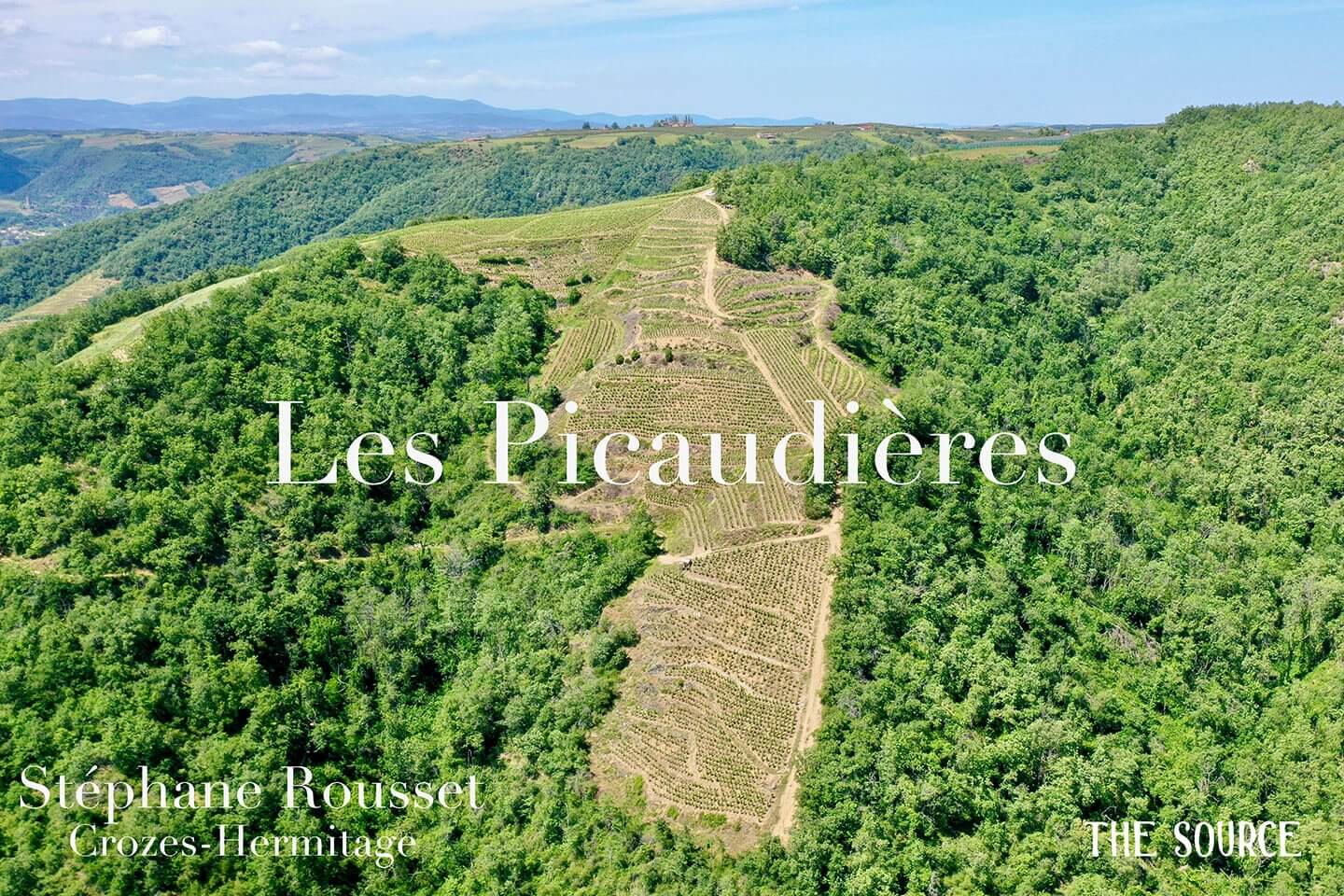

Crozes-Hermitage, the appellation home to the majority of Rousset’s collection of vineyards, is the most diverse terroir in this region under the red grape variety, Syrah. (There’s white too, but a much lower production volume.) In this appellation everything from the acidic metamorphic and igneous rocks all the way to alkaline-rich limestones, wind-blown loess and river alluvium can be found. And all occur on various exposures, some on flat land and some on treacherously steep hills (like Rousset’s Les Picaudières) with every possible soil grain, from clay, silt, sand, gravel, cobbles to boulders! Geologically, Crozes-Hermitage is laid out as if Hermitage had been stretched and pulled in every direction away from the river, toward the north, east and south.

The criticism of Crozes-Hermitage comes in the form of the vastness of its terroir and the often ordinary nature of its Syrah, a grape that manages to deliver a lot of flavor and pleasure even from the lesser terroirs. Many are blends of different parcels and the vast majority are often considered delicious and easy-going, but without any particularly compelling attributes that further define it. They are indeed vins de terroirs, but many of the appellation’s terroirs aren’t nearly as compelling as those from Hermitage, Saint-Joseph, Cornas, and Côtes-Rôtie. But there are exceptions and one needs only to do some research within this vast appellation and its seemingly endless supply of growers.

Rousset’s Vineyards

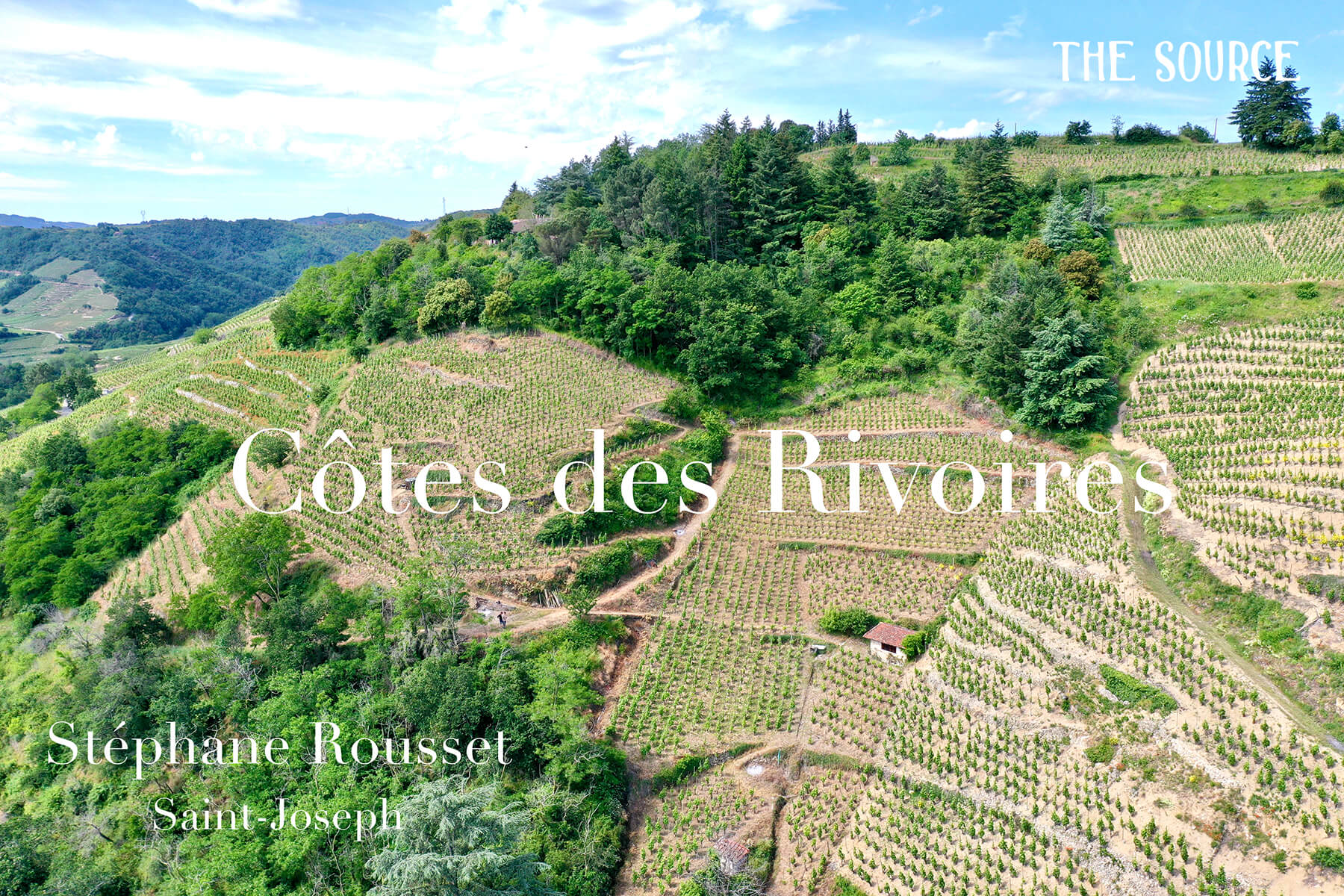

To the north and behind Hermitage, on the same side of the Rhône River, is the setting for Stéphane Rousset’s vineyards, on the granite lands of Crozes-Hermitage. Aside from the greatest vineyard in Rousset’s stable, Les Picaudières, they have many parcels in the appellation’s three historic communes of Gervans, Érôme and Crozes-Hermitage, the latter of which being the small village from which this massive AOC takes its name. Across the river is a terrific set of side-by-side, east-facing Saint-Joseph granite parcels named, Les Rivoires, that Stéphane bottles simply as a Saint-Joseph appellation wine but is perhaps deserving of a demarcation of its origin within the original six communes of the appellation before it was expanded to cover most of the ground on the right bank (west side) between the original six communes and Condrieu.

Stéphane and his father, Robert, tend to the vineyard work together, and a stroll through their vines reveals an extremely high quality of farming from this two-man team. They respect the soil and nature, and minimize the use of copper and sulfur treatments in the vines—though both are essential in all European vineyards whether or not they are practicing organic, biodynamic and/or a “natural” winegrowing. Nature abounds in this specific area of Crozes-Hermitage and the Roussets embrace it, which also seems to be perceptible in the wines, with their large range of savory characteristics and less punchy fruit.

Wine Crafting

In the cellar it’s pretty straightforward. Located on an unassuming and unmarked road, a first glance inside instantly reveals Stéphane’s attention to detail. His fastidiousness is obvious, even when he’s thieving with his pipette to taste from his barrels, as hardly a drop ever hits the floor. Like many of the cellars in the Northern Rhône Valley, their approach is similar to what one would see in a California wine cellar with Syrah as part of their production.

The red wines are made with fully destemmed grapes (sometimes exceptions are made in warmer years) and the use of 225-to-500-liter French oak barrels, with a minimum of new oak mixed in, and only when barrels in disrepair need replacement. Certain portions of the basic red Crozes-Hermitage are aged in stainless steel, which seem to be parcels largely grown on granite bedrock with loess topsoil, and then blended in with some of the wines raised in oak barrels from parcels that are largely grown in granite bedrock with granite topsoil. The Crozes-Hermitage Rouge “Les Picaudières” and the Saint-Joseph are raised exclusively in oak barrels. As a side note, Rousset has a fabulous collection of Crozes-Hermitage vineyards that I’ve encouraged him to bottle alone. I’m happy to report that it’s finally happening after four years of discussion, starting with a particular site that has been gorgeous out of barrel every time I’ve tasted it.

His whites made from Marsanne are mostly aged in stainless steel tanks, with a small proportion of French oak barrels. The steel is employed to inhibit malolactic fermentation by temperature control and to preserve the elusive freshness whites from this region struggle to maintain. And while we are ecstatic about Rousset’s reds, his whites are irrefutably considered within the best of the Northern Rhône.

One of the most diverse appellations in France’s Northern Rhône Valley, Crozes-Hermitage is also its biggest. As already mentioned, Rousset’s vineyards are in its most northern communes: Érôme, Gervans, and Crozes-Hermitage. The soil types and hill structures here differ greatly from the rest of the appellation. They are on moderately steep to very steep igneous rock terraces (with a very small amount of metamorphic rock) of the river’s left bank, above the Rhône and tucked back behind the famous Hermitage hill.

Rousset’s vineyards are just north of the Rhône River’s hard left turn that wraps around the south-facing Hermitage. The river carved out this narrow gorge, exposing hard granite rock on each side. This section on the left bank (east side) yields wines of texture and perfume from what we more commonly associate with Cornas and St. Joseph, minus the solar power of those more exposed appellations. Les Picaudières, in the commune Gervans, is historically one of the most revered terroirs inside of Crozes-Hermitage. With its granite and schist-like shards, nearly devoid of topsoil thanks to the steepness of the hill, gravity and hard bedrock, it may be one of the most singular wines from the entire appellation and surely one of its most recognizable when tasted. We haven’t seen or heard much about this historic vineyard from the legend now a few generations past, Raymond Roure, sold to Robert Rousset (Stephane’s father) some decades ago, but its history is worth further investigation.

Crozes-Hermitage is home to France’s noble and rustic red, Syrah, and the whites, Marsanne and Roussanne. In its three original communes the soil for Syrah is largely granitic, but with many small variations of igneous and metamorphic rocks, as is the case of Les Picaudières. His whites, composed of Marsanne, grow mostly on loess, a fine-grained crystalline soil blown in by the wind that results in deep topsoil deposits above granite bedrock on many of Rousset’s vineyards by the river. Loess is a slightly yellowish white color, rich in minerals and calcium, and ideally suited for white wine more than red. Across the river, in Tournon, one of the six original Saint-Joseph communes before numerous expansions, Rousset’s two parcels of St. Joseph are on pure granitic bedrock on a treacherously steep hillside.

A Shorten Version of the Geological History

The geologic setting of the region is interesting and worth bringing into the conversation because it is a significant defining factor between the goût de terroir of certain communes. We go back as far as the Massif Central’s conception more than three hundred million years ago, which is responsible for the granite and metamorphic outcrops found in the Northern Rhône. Now we should pick up the story with the Alpine orogeny and everything that transpired during and after this geological event that is still underway today.

The Alpine orogeny (mountain building event) began around forty million years ago and has carved out the Rhône Valley that sits between today’s Alps and France’s Massif Central and has resulted in opposing geological settings in Crozes-Hermitage and Hermitage where on one end sits the ancient granite bedrock of the Massif Central, while on the other, there is a multi-layered alluvial deposition largely brought in by the Rhône and Isère Rivers, whose torrential clashes over the years are most evident on the south and eastern zones of the region. The Rhône River is also responsible for the separation of the western section of Hermitage and Crozes-Hermitage from their granitic geological kin across the river.

Granite, one of the darling rock types of the Northern Rhône Valley, is all too often misattributed as the mythical legendary soil of Hermitage. It is indeed an important part of the hill, but it makes up only a small portion of its western flank—perhaps around 15%. The rest of the hill is a layer cake of different alluvial depositions, some rich in calcium carbonate soils (limestone marls, loess, and more) laid down over the last few million years, with the last of the depositions in the form of river alluvium cobbles, gravel, sand, silt, and sometimes clay.

Crozes-Hermitage represents a strongly terroir-diverse region where those with modest budgets can explore the differences soil can impose on a wine. And despite Syrah’s naturally strong vinous characteristics, it is a wonderful transmitter of its terroir, whether or not the terroir can deeply mark its wines. Certain producers represent specific areas principally on different terroirs within the appellation. To cite a few examples: Alain Graillot’s wines come from the Chassis plain on river alluvium, similar to the lowest vineyards of Hermitage, Domaine du Colombier’s wines from Mercurol are on a mix of alluvium with limestone deposits similar to Hermitage’s eastern side, and Stephane Rousset’s are grown on mostly granites similar to the western flank of Hermitage.

The only way to be relatively sure of the specific separation of bedrock and topsoil is to be diligent in your research of where each vigneron’s parcels are located within the appellation. Almost all of the wines only display the appellation name on the label. Insider tip: find the name of the village where they live, which is usually written on the label, and locate it on a geological map. The likelihood is that their vines are nearby, so that’s a good place to start digging.

The Climate

Microclimates are an important influencer on Crozes-Hermitage wines. Rousset’s differ quite a lot from those on the fully exposed Chassis plain, or even up into Mercurol. The climate in the area behind Hermitage where Rousset’s vineyards are located tend toward warm days, but most of his vineyards are close to the river gorge and are also influenced from the surrounding forests. In the woods and next to the river the air cools quickly at nightfall, refreshing the vines and giving them more time to prepare for the next day’s heat. However, there are moments in the summer when the air goes still and the sun’s power is intense enough to alter the course of an entire vintage within a couple of days, as it did in 2016 where the wines that were picked even days after the heat went crazy show more dried fruit characteristics and higher alcohol. The winters are brisk but not extreme, except for the penetrating winds that often catch people off guard when dressing for a sunny day. The Rhône River also contributes to moderating the temperatures, but likely less than in the past, as hydroelectric dams now dramatically slow the currents from what they previously were in the spring and early summer.[cm_tooltip_parse] -TV [/cm_tooltip_parse]