La Casaccia

This website contains no AI-generated text or images.

All writing and photography are original works by Ted Vance.

Short Summary

In the Monferrato Casalese village of Cella Monte, agricultural science majors, Giovanni and Elena Rava, took over La Casaccia in 2001 and converted it to organic farming. A remarkable ecosystem of natural and human-made biodiversity surrounds the vineyards, which sit on four geological formations rich in a variety of calcareous and terrigenous sands, silica, silt, limestone, marl, and clay. Their entry-level wines are all made in a straight-forward style with natural fermentations with 3-15 days of skin maceration on the red varieties with little to no pressing (only free-run wine) and light, soft extractions. The organic wines have a style that’s pure, clean, fun, and full of flavor.Full Length Story

In all of Italy, even with its abundance of enthusiastic and character-filled vignaioli, it may be impossible to find another soul who emits as much bubbling enthusiasm and pure joy for their work as La Casaccia’s Giovanni Rava; la vita è bella for Giovanni and Elena Rava, and their children, Margherita and Marcello. Working together in a life driven by respect for their land and heritage, they also offer accommodations to strangers (who often become friends) in their restored bed and breakfast, a great place for anyone looking for a more serene Italian experience. Organic farming was a must for them from their start in 2001, and they were certified three years later. In the Monferrato Casalese area, their vineyards are scattered throughout the Cella Monte countryside on many different slopes teeming with natural biodiversity expressed in various forms of agriculture, untamed forests, and wild fruit nut trees. Their traditionally crafted wines come from vines on soft, stark white chalk with layers of eroded sandstone, and are lifted, complex and filled with the humble yet exuberant character of la familia.

Ones in Thousands

Importers receive tons of daily email inquiries from producers seeking representation in the US—literally thousands have come our way over the last decade. All inquiries are viewed but extremely few are in line with our interests. However, an unexpected inquiry from Margherita Rava was a welcome surprise, a serendipitous completion of a circle that had already been started—an event maybe akin to what we sometimes call fate, if one believes in such things.

We worked some years ago with an Italian wine importer who represented La Casaccia early in our partnership. While my interaction with La Casaccia’s wines was brief—and I’ve never understood why the importer parted ways, nor does the Rava family—I remembered their wines, especially the extremely pale-hued red with tight lines and an ethereal demeanor. Of course I’m referring to their Grignolino del Monferrato Casalese.

It was bitterly cold and I was frozen to the marrow on my first visit to La Casaccia over ten years ago, which made it harder for me to thoroughly appreciate Giovanni’s snow-melting warmth and joy as he led us with his ever-present smile for what seemed to like a five-mile walk (it was probably only a thousand yards) over the thin, brittle and crackly layer of snow blanketing Cella Monte’s gently-sloping hills. As the wind whipped us relentlessly, stinging and burning our faces, we came to a soil-cut in the road, exposing the area’s chalky soils, as white as the snow, which had developed under a warm and shallow sea tens of millions of years ago. The icy cold but soft and friable fragments that we attempted to take home to California crumbled in our hands and further fell apart in our pockets as we made the highly anticipated trek back to their historic cantina, and the memory of that moment was now frozen in my mind.

Not only winegrowers, the Ravas are also hospitalitarians committed to the service of others in all they do at their Agriturismo. More recently, as I passed through the limestone gate of its northeast entrance, a feeling of insulation, and even protection, from the pressures and pretensions of the world immediately set in. Worries about home and work melt under the hot Piemonte sun (as did the shivery recollection of that freeze, a decade ago), and the Ravas awaited us, smiling from ear to ear. To spend time in their ancient interior courtyard from centuries ago and to experience the warmth of the Italian culture written about in books, La Casaccia and its stewards are a true Italian experience—only quieter and much calmer than the serious intensity of many Italian family encounters; at least until Giovanni reenters the orbit, vibrating with joy he can hardly contain as he constantly erupts with laughter and excitement.

The world is full of Arrigos, and they should be remembered and credited for their contributions. Many people like him who lack heirs, still pass on to others precious knowledge that would otherwise have been so easily lost.

Not only does the Rava’s joy also emit from their wines, which are designed with respect for La Casaccia (a UNESCO world heritage site), with its ancient, deep Pietra da Cantoni ant-farm-like tunnels carved out of the limestone by hand below the manor and courtyard, they also work to honor the people who came before them—their family, and their very special friend, Arrigo.

Arrigo Cencio, a retired vignaiolo without familial heirs for his possessions and knowledge, took Giovanni and Elena under his wing upon their arrival to La Casaccia. They had completed their Agricultural Science studies specializing in plants, at the University of Torino, and returned to Elena’s family’s village, Cella Monte, in search of a more rural, peaceful, and meaningful existence connecting with and preserving nature on their family’s land.

Arrigo was seventy when they met. Because he had no children, he closed his winery but quickly regretted it when he began to sell his winemaking materials. Much of his equipment went to the Ravas, and he invested his later years in teaching Giovanni and Elena everything he knew from his lifelong passion and knowledge for grape growing and winemaking. Arrigo’s winery was called La Casaccia, and in honor of him (and to continue with his clients as a built-in business) the name was preserved. During the first fifteen seasons Arrigo worked with them during harvest, vinification, and bottling. Now in his nineties, he’s still full of energy and enthusiasm but only visits occasionally to check on them. The world is full of Arrigos, and they should be remembered and credited for their contributions. Many people like him who lack heirs, still pass on to others precious knowledge that would otherwise have been so easily lost.

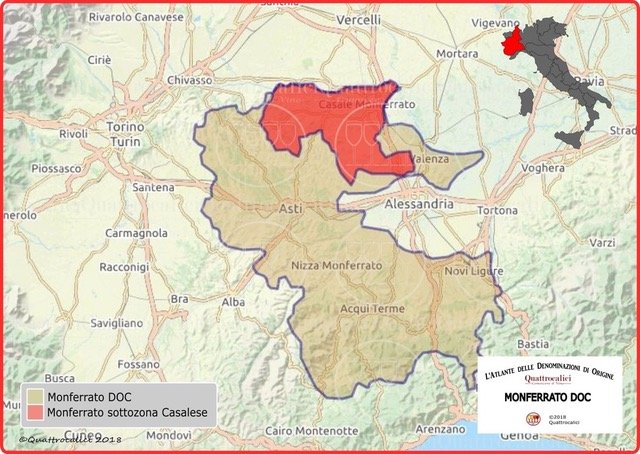

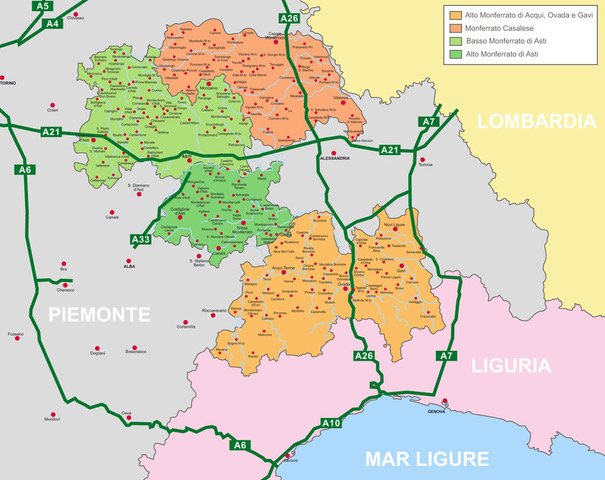

Monferrato DOC

Monferrato can be confusing. First governed by Aleramo, the Marquis of Montferrat, who also controlled Liguria, Monferrato is a historical area established around 900 A.D. Its historical borders are approximately the same today, although they are informal and cross into both the Asti and Alessandria provinces. Entirely within the Alessandria province in the north and eastern side of Monferrato is Monferrato Casalese, and in the far south, bordering Liguria’s northern border, Alto Monferrato di Acqui, Ovada e Gavi. Inside of the Asti province, on the northwestern side is Basso Monferrato d’Asti, and in the center, Alto Monferrato d’Asti.

Inside of Monferrato there are many different DOCs and DOCGs, and many overlap between the two formal provinces, Asti and Alessandria. The Monferrato DOC is quite flexible, and one can produce about anything they want with this generic DOC on the label (e.g. Monferrato DOC Nebbiolo, Monferrato DOC Barbera, Monferrato DOC Chardonnay, Monferrato DOC Rosso, Monferrato DOC Sauvignon, Monferrato DOC Pinot Nero, etc). It can come from different areas inside Monferrato (sometimes overlapping the formal provinces, as Barbera d’Asti DOC does) from different terroirs with very high yields. The largest part of the wines produced in this general DOC are priced quite low and are often from yields of 9,000-11,000 kilos of grapes per hectare.

Monferrato del Casalese DOC Rules

Entirely inside the Alessandria province, the Monferrato del Casalese appellations are in the northern end of the greater Monferrato area. Inside parts of the area are zones that may still use on their labels the Asti DOCs, like Barbera d’Asti, or Grignolino d’Asti. However, every wine at La Casaccia is labeled under Monferrato del Casalese DOC or the Monferrato DOC. Each appellation has its own set of rules, some more complex than others. For example, Grignolino del Monferrato Casalese must be 95% Grignolino and can only be mixed with either Freisa or Barbera, while Grignolino d’Asti’s minimum is 90% and can contain a bigger range of varieties in the remaining 10%. The yield limit for Grignolino del Monferrato is 56hl/ha, while Grignolino d’Asti is a maximum of 80hl/ha—quite a difference. There are many more rules, but they are far too extensive to cover.

The official “unofficial” historical area of Monferrato is confusing. Some maps show three subzones, while others show four. From a general point of view, Monferrato Casalese and Basso Monferrato (also referred to as Lower Monferrato Astigiano) are the “unofficial” Monferrato areas of the north. Here, the weather is typically warmer and drier than further south in Alto Monferrato (or Upper Monferrato Astigiano) and the fourth and most southern unofficial zone, Alto Monferrato d’Acqui, Ovada and Gavi. There will indeed be discrepancies of opinion as to how to name these unofficial subzones, but for the sake of clarity, we will base them on the image above.

Farming Philosophy

As mentioned, Giovanni and Elena started organic farming in 2001, their first year at La Casaccia, and certification was attained three years later. They haven’t tried biodynamics yet, but Margherita is interested in experimenting. No treatments in their vineyards outside of organically accepted copper and sulfur sprays, and the nationwide obligatory spray for the vector (a leafhopper, similar to the US’s sharpshooters) that causes flavescence dorée, a phytoplasma disease that eventually leads to the death of the plant if not physically cut out of the vine before full infection. The approved organic spray for flavescence dorée is Piretro, an extract derived from the dalmatian flower that is much less destructive on the entire insect community than conventional treatments.

What’s most important for La Casaccia’s vineyard culture is the strength of the natural and human-made biodiversity surrounding every vineyard area around Cella Monte. Indigenous woods and nut and fruit trees (including epic wild cherries) grow wild everywhere around the cultivated landscape. In fact, there is so much brush and forest that act as safe harbor for bugs (leafhoppers, hornets) and animals that love to terrorize vineyards canopy growth (like deer) as well as others that swoop in once the berries are ripe (birds, wild boar) that end up doing their evolutionary duty of helping to propagate the seeds of the grapes they eat.

From an outsider’s perspective, it’s hard to look at the vineyards of La Casaccia and think that much more needs to be done to encourage nature. Margherita says they achieved a natural balance in their vineyards about ten years after committing to organic farming (of course with a lot of help from the surrounding nature as well) and very little has changed or improved more from that point.

General Red Wine Cellar Practices

All La Casaccia’s cellar practices vary based on the particularities of each season. Decisions for Grignolino and Freisa are based on acid and tannin levels, and with Barbera it’s mostly influenced by the acidity.

All grape varieties are destemmed, aside from a few years in the past when some were included in Barbera during colder, wetter years that didn’t ripen enough. Spontaneous fermentations are the norm, and delestage (rack and return; a method in which the juice/wine is emptied almost entirely from the vat, separating it from the skins, and then pumped back over on top of the skins) is employed more than in the past to work in a gentler way and to ensure the grape must receives a plentiful supply of oxygen to counter unwanted reductive elements. Grignolino spends about three days on skins, Freisa five or six, and Barbera ten to fifteen.

At La Casaccia, they don’t actually press any of their red wines. They only allow the free-run juice to make up the entirety of the wines, and the leftover pomace/grapes are sold for distillation for grappa; only the finest and most elegant parts of the wine make it into bottle. This choice is usually only done with very expensive wines, not those with the prices of La Casaccia. It’s honestly unexpected, and a big reveal of why their wines are so elegant. What a commitment to quality!

The reds are racked four to five times during cellar aging to remove sediments and to further work against reductive elements when present. Depending on the wine, various vessels like stainless steel, fiberglass and oak are used for aging. Sulfite levels for reds range between 40-60ppm, with the first micro addition made at fermentation and the greater dose at bottling.

Grignolino

Ideal for today’s consumer in search of lighthearted but authentic and terroir-dense wines, Grignolino offers the classic cultural tastes and smells of Piemontese wine. Piemontese reds are known to beg for food, but despite Grignolino’s naturally high acidity and potential for firm tannins, most versions don’t require a meal to deliver harmony and are quite fun to drink alone. Of course, many try to be very serious and cerebral, but most tend to fall short, with a dulling heaviness that clips some of its best traits.

“Grignolino is the Nebbiolo of Monferrato Casalese.” – Giovanni Rava

Naturally pale in color, Grignolino is enticing and reminiscent of fresher vintage Nebbiolos with those unique Giuseppe Mascarello-like, reddish-orange tones but with a much lighter hue and usually much lower alcohol and extracted tannin level. Young, fresh, and unoaked Grignolino seduces with a constant emission of pheromonal scents fluttering from the glass, typically accented with sweet red and slightly purple flowers, tart but just ripe berries and a little flirt of that indescribable but inimitable Piemonte red wine spice and earth. Superficially, simply-made Grignolino is invitingly poundable, delicious fun, but in more intimate encounters with its most talented makers, its interior strength and depth reveals a more distinguished nobility.

With the unique combination of rosé-like light pigment, high acidity, and the possibility for very firm tannins (a generalization that could also easily be used to describe some Nebbiolos), Grignolino is often macerated during fermentation for shorter periods than most grapes, principally to manage its potential for massive seed tannins, but also to preserve what little color pigments it has and to keep them brighter than darker. In wines meant to be drunk young the grape must/wine is often “let” from the skins (see General Red Wine Cellar Practices above). In the case of La Casaccia’s Grignolino del Monferrato Casalese “Poggeto,” this usually takes three days, well before the full deterioration of interior grape membranes. This keeps from fully exposing this grape’s heavy seed count to the increasing level of alcohol that will further extract seed tannins. With this approach, one could also pick earlier to highlight the variety’s natural charm with an even redder, crunchier spectrum of fruit ripeness—hallmark characteristics that seem to serve this wine better than those with more extensive wood contact and ripeness on the vine. All of this makes for a wine with a lot of pleasure without missing any details that reveal its regional DNA. It also makes for wines perfect for the current market’s interest in crunchier, fresher wines.

Nebbiolo never really took hold in Monferrato Casalese because it was not the traditional variety of the area, although there is more planted each year along with a greater nudge with the recently added Monferrato Nebbiolo appellation. Giovanni says, “Grignolino is the Nebbiolo of Monferrato Casalese,” and by this he means many things. First, while Barbera is the most prolific red grape in the greater Monferrato area it shares no genetic relation to Nebbiolo, whereas Grignolino does and maintains similar familial structural elements and color—although much lighter by nature than the already quite pale-colored Nebbiolo. (Indeed, Freisa is also genetically related to Nebbiolo, and even more Nebbiolo-like in some respects than Grignolino, but it seems lost somewhere between Alba, Asti, and Casalese Monferrato.) Nor does Barbera carry many other traits comparable to Nebbiolo, except for its excellent acidity levels. He also explains that while today it may be hard to believe based on the more recent history of Grignolino compared to Nebbiolo, it shared a similar historical prestige, and in the 1800s, Grignolino from Casalese was considered the equal in quality and price of the Langhe’s Nebbiolos. Of course, this predates by more than a century the evolution of Barolo and Barbaresco into the glorious red wines they are today, a century in which those areas were mostly used for sparkling wine production.

According to Ian D’Agata in his book, Italy’s Native Wine Grape Terroirs (a must for anyone serious about Italian wine, or just simply interested), the Grignolino wines were prized as far back as the thirteenth century but lost favor in the last thirty years or so and were replanted with other grapes that had a stronger market value in the Langhe and elsewhere. D’Agata pushes the merits of Grignolino in his book and loves the wines, and we can see why. It seems to have all the ingredients to really thrive in today’s market led by younger wine professionals who are more than willing to pay for the highest levels of nobility when they lead with extreme subtlety rather than power. Had Grignolino held court in prized Langhe vineyards and with its most advantaged positions on the hills with today’s swing for many from power to elegance, it may have held the number two spot just below Nebbiolo, leaving Barbera and Dolcetto to duke it out for third. But what brave soul would dare rip out Nebbiolo in a prime position in Barolo or Barbaresco to see what happens with Grignolino in its perfect spot?

There is no region more historically famous for high quality Grignolino than the Monferrato Casalese area. In places like north Monferrato, under the labels of Grignolino del Monferrato Casalese, they can be gorgeous and with, on the average, a little more substance—without losing their freshness and charm—due to their greater content of limestone marl mixed in with sand than what is typical of Grignolino wines grown in other parts of Monferrato on sandier soils labeled as Grignolino d’Asti. Of course, these regional soil elements vary from plot to plot, so broad generalizations often need to be thrown out the window.

La Casaccia’s Grignolino del Monferrato Casalese “Poggeto” could be viewed as in the middle ground on the elegance chart—within the context of Grignolinos, of course. Planted between 2003 and 2010, it’s always grown on the top of the hills on the sandiest soils loaded with chalk. Poggeto is filled with the spirit of deep joy and generosity of the family delivered with impeccable craftsmanship led by their intention to create a spherical balance throughout the entire wine.

They also make Grignolino del Monferrato Casalese “Ernesto,” an homage to Grignolino’s likely historical style when they were fermented longer, thus requiring longer aging in barrels (in this case, three years) and in bottle for at least two years to soften up those bigtime tannins. While it comes from the same young-vine parcels as Poggeto, it yields a very different wine with darker, more powerful and savory notes.

Barbera

Despite its non-native status in Monferrato, Barbera is the regional sheriff and the breadwinner for most red wine growers. The variety supposedly originated in southern Italy centuries ago and began its mass proliferation sometime after phylloxera hit. (It’s thought to have first arrived from Sicily or Campania, though the debate about this and when it arrived in Piemonte is still alive.) Today, it’s ubiquitous in much of Piemonte and there is a lot of it in the marketplace, which, thankfully, keeps the prices down, even for wines from top producers in Barolo and Barbaresco.

Barbera is indeed a bit of an outsider in Piemonte. It’s easy to spot in a blind tasting of Piemontese wines because of its abundance of acidity and lack of tannins—the exact structural inverse of Dolcetto. It also typically requires a greater alcohol potential to achieve phenolic ripeness that moves it away from unripe seed tannins (the few that it has) and the potential for unbalanced, high acidity. Barbera is also uniquely suited for its best results with warm summer weather during the daytime and nighttime, the opposite of other Piemontese grapes that need the daytime heat but colder nights to reach their heights—another clue to Barbera’s possible origin from the south where day and nighttime temperatures don’t fluctuate like those in the north, or deep inside the Apennine range, away from the sea.

La Casaccia’s Barbera del Monferrato “Giuanìn” comes from vines planted between 2004 and 2010. These young and vigorous vines create a wine with great lift and slightly less concentration than most old-vine Barberas. Barbera vines are planted usually in the middle of the hills, below the Grignolino and above Freisa, where the mix of chalky sands and clay further downslope are in perfect balance for this grape that seems to thrive well in just about any Piemontese soil. Barbera is preferential to more humid and precipitous environments, and in Casalese’s driest and warmest seasons it can be the first picked between Grignolino and Freisa, while the former is almost always picked first and the latter last, an order that is determined by variety as well as hill position and soil composition.

They also have two Barberas aged in wood, Barbera del Monferrato “Calichè” and Barbera del Monferrato “Bricco dei Boschi.” With a similar stable of young vines planted after 2000, these wines are more concentrated and grounded than the higher-toned Giuanìn. They also show more oak notes in their youth and require many years of cellaring to achieve Giovanni’s intended outcome.

Freisa

We don’t know what Giovanni Rava did with their Freisa Monferrato “Monfiorenza,” but we were completely swept away by its charm, a descriptor that would rarely be used for this grape. Their Grignolino “Poggeto” is lovely and one of the most substantive and beautiful, fresh-style wines in the Grignolino world, but their Freisa is something altogether unique and utterly accessible for this little-known but historic variety commonly led by coarse rusticity and deeply savory notes. In 2021, we went to La Casaccia to seduce Poggeto and came away with Monfiorenza on our arm as well. We’re not sure about its ageability, but who cares; it’s a wine to feast on in its youth and wait as patiently as possible for the next scrumptious batch.

What put Freisa on our radar initially (as for probably many other wine lovers) were the ones from the great producers like G. Rinaldi, G. and B. Mascarellos, Cavallotto, Brovia, and Vietti, who all keep it in their ranges. And they must still do so for a good reason, no? It’s true that youthful Freisa can approach with the grace of an angry bull, but in the right hands, its untamed and reductive nature can at least be harnessed and led toward a gentler appeal so that maybe it ages into something wonderful and worthy of note. Freisa may eventually gain the respect of the general international community of Italian wine lovers, but it needs the right ambassadors—although the mentioned Barolo producers are not a bad start! However, Freisa will still be grown in Barolo and Barbaresco mostly positioned on the vineyard in subordinate locations to Nebbiolo. Few winegrowers can justify keeping Freisa in a prime time Nebbiolo spot, if not only for historical preservation, then for financial reasons.

We don’t plan to stand on the hilltop to shout the universal merits of Freisa as we will with Grignolino, but at the very least La Casaccia’s is an inexpensive entry-ticket to an authentic Piemontese red that covers all the bases and then some. In a Decanter article, Ian D’Agata is quoted as saying that aged Freisa is sometimes hard to distinguish from Nebbiolo. Despite our lack of in-depth experience in the subject, we believe him.

Other La Casaccia Wines

There are some fun and fabulous surprises in La Casaccia’s world of white wines. First is their Piemonte DOC Chardonnay “Charnò” grown exclusively on chalky soils, called terre bianche (white soil), and on east and southeast positions so it doesn’t ripen as quickly as it would facing direct south, southwest, or west. This wine echoes France’s northern white wine areas on limestone bedrock and soil known for their deep mineral notes and vibrant acidity, like Chablis, Sancerre and all the way over to Saumur. It’s a joy to drink and demonstrates what can be achieved with Chardonnay outside of France on similar soil types and made in a way that exposes its wonderful terroir. The best part about this wine is that it tastes like a white wine from limestone soils before it tastes like a Chardonnay.

Another fabulous wine in the range is their Metodo Classico sparkling wine labeled La Casaccia Brut, a pure blend of nearly equal parts Chardonnay and Pinot Nero/Noir grown on chalky limestone soils. The wine is aged for two to four years on the lees (because they don’t make it every year and there are many disgorgements on the same vintage) and stored in the deepest and coldest part of the cellar. The dosage is variable and depends on the fermentation in bottle. Some years there is no need for dosage because of small amounts of natural residual sugar. La Casaccia’s Brut stands as one of the most classically Champagne-like sparkling wines in Piemonte.

Climate and weather challenges of Monferrato and Cella Monte

While Monferrato is typically a bit more arid than the neighboring Langhe and Roero, and far drier than Alto Piemonte perched in the north at the base of the Alps, Margherita’s great uncle, Luigi, used to say, “Al Munfrà l’è trop suc o trop bagnà:” Monferrato is too dry or too wet.

Most of the consequential storm systems come from the west and north, out of the Alpine glacier-carved valleys, Val Susa, west of Torino, and to the north from the ValSesia, a group of valleys with the largest separating the Alto Piemonte appellations, Boca and Ghemme (among others), from those across the Sesia River, like Gattinara, Bramaterra and Lessona.

Hail is generated even into the summer months when the cold winds of the north tangle with the warm and damp Mediterranean clouds that blow in from the south. Updrafts caused by storm conditions push rain up into the freezing northern system where hailstones begin to form, and they fall when they’re too heavy for the updrafting winds to keep them afloat. The Ravas note that over the years more rain and hail falls just north of the Monferrato hills in lower-lying areas closer to the Po River, which begins its journey from Monviso, near Cuneo, where it empties into the Adriatic, near Venice. Another one of our producers in Nizza Monferrato in the south, Gino Della Porto, from Sette cantina, said that the areas of Monferrato closer to the Apennine Mountains, like Nizza, are also more impacted by hail than the areas of Monferrato around La Casaccia further north. However, in general, most of the rain falls before reaching Monferrato, making it one of the driest areas in all of Piemonte.

Frost has yet to be a big problem, at least in Cella Monte, the location of all of La Casaccia’s vineyards. It threatens on occasion but mostly finds its way down to the lower parts of the valleys where vines are rarely cultivated.

Geology: Monferrato Casalese DOCs

(The geology sections are researched and compiled from various sources by MSc Geologist, Ivan Rodriguez)

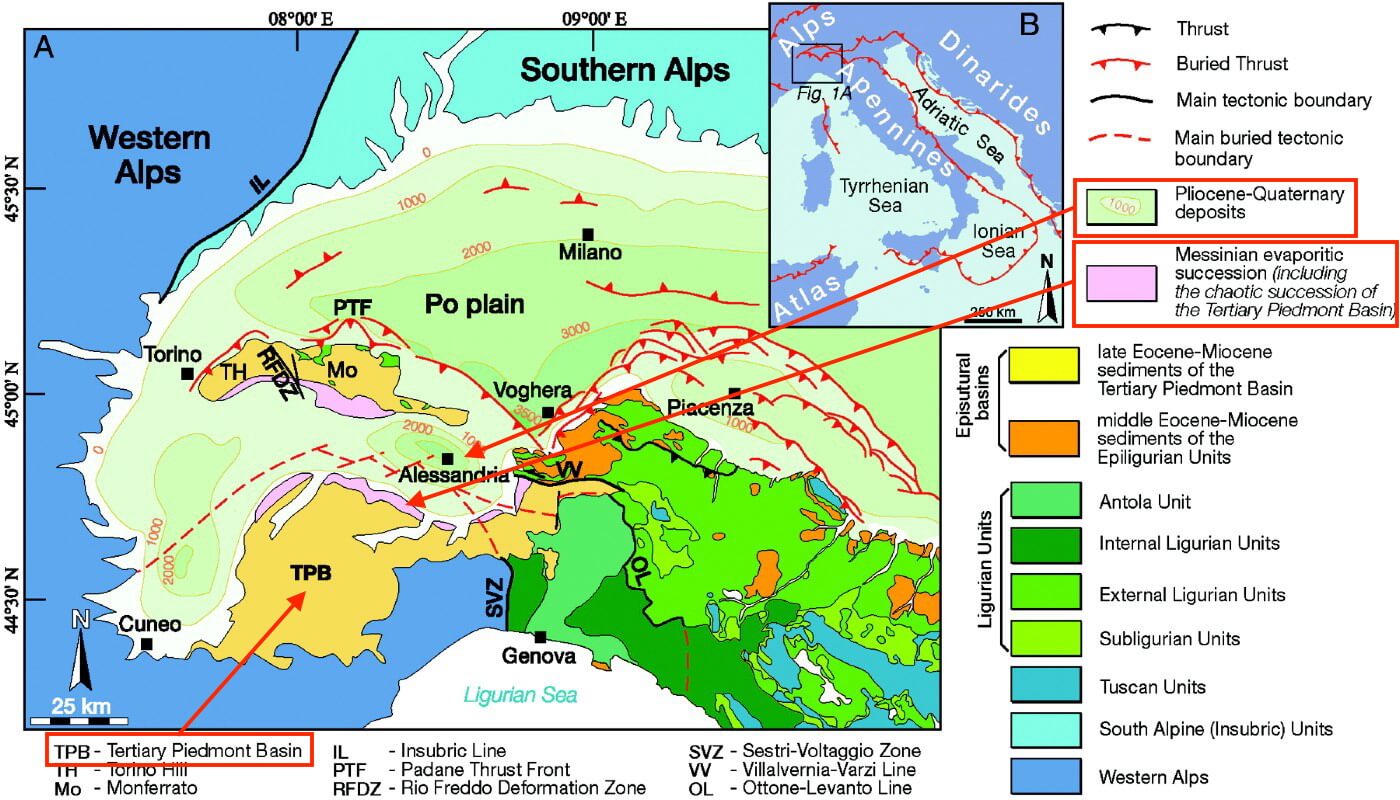

The Monferrato Casalese’s DOC areas are located over the foothills of the Torino-Basso Monferrato Hills. This chain of hills that are relatively high compared to central Monferrato, extends through a ten kilometer-wide, west-to-east band starting in Torino and ending in Casale Monferrato. (You can read more about this on our producer profile of Sette.) These hills are part of what geologists refer to as the Piemontese Tertiary Basin, a succession of sedimentary deposits that occurred between 38 and 5 million years ago that also includes wine-producing areas like Roero and Langhe. They are considered the northernmost part of the Apennines mountains.

The origins of the Apennine Mountains and the Piemontese Tertiary Basin are a result of the Alpine Orogeny, and all of Monferrato’s geological units were formed during this mountain-building event. The most crucial element for Monferrato’s geological setting for viticulture is a former sea once located in and around what is today’s Po Valley. Several factors affected this sea’s depth, composition, and environment.

Two geological processes that took place around 20 million years ago had a significant effect on Piemonte. First, the Tyrrhenian Sea (located between today’s Italian peninsula and the islands of Corsica and Sardinia) began to widen due to tectonic activity, which made the continental crust thinner. On the other side of Italy, where the Adriatic Sea is located, subduction processes (one tectonic plate moving underneath another) resulted in a compressional force. This affected the thinning continental crust and began to compress, further developing the Apennines, a mountain chain that extends from northern Italy down to Sicily. Starting less than three million years ago, the combination of these tectonic movements and the sediment infill from the erosion of the newly forming Alps and Apennines would fill the sea and turn it into a fluvial basin, now known as the Po Valley, or Po Plain (or in Italian, Pianura Padana), a significant part of of Italy’s Piemonte, Lombardia, Veneto, and Emilia-Romagna landscapes. Monferrato Casalese vineyard areas border the Po Valley but are largely composed of the marine sediments from the ancient sea.

Geology: La Casaccia

In the area around Cella Monte, home to La Casaccia, several geological formations come together in a short space resulting in a rich variety of sediments (both calcareous and siliceous) ranging in different oceanic environments from near shore to deep sea, depending on the past changes in sea level and the local tectonics.

There are four principal formations important to this area. Starting with the oldest and moving into the youngest is the Cardona Formation, an alternation of non-calcareous sediments of conglomerates and sandstones (as pictured above), with occasional layers of calcareous marls, all developed between 34 and 28 million years ago and formed in a near-shore to shallow-sea environment. The Antognola Formation corresponds with a continental slope environment (a transition from shallow to deep sea) and is formed by silty marls with interbedded bodies of sandstones and conglomerates developed 28 to 20 million years ago. The Pietra da Cantoni Formation, the rock of La Casaccia’s web of underground cellars, is formed by calcarenites and sandstones from 20 to 16 million years ago and corresponds to continental shelf deposits (shallower marine areas). Finally, a resedimented evaporite unit (a sedimentary rock, such as gypsum in this case, that originated by evaporation of the seawater in most of what is today’s Mediterranean Sea) known as the Complesso caotico della Valle Versa was formed by flooding just after the Messinian Salinity Crisis, when today’s Mediterranean seabed was mostly dried out and covered in gypsum-rich deposits and layers of pure gypsum. This produced a partial erosion of the gypsum-rich depositions formed during that event, resedimenting them with a mix of marine and terrigenous sediments.

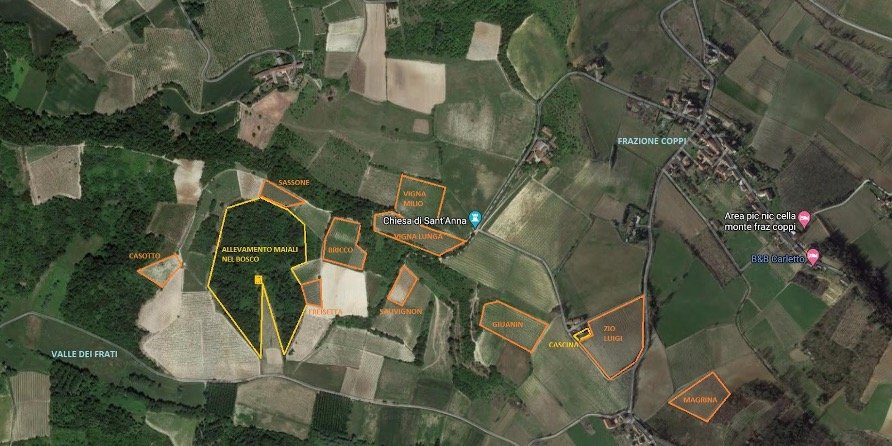

All these geological units converge around La Casaccia with a tremendous variation of bedrock and topsoil ranging from calcareous sands, terrigenous sands, silt and clay. In most of La Casaccia’s westernmost vineyards (Casotto, Sassone, Bricco, Freisetta, Vigna Milio, Vigna Lunga, and Sauvignon–the latter named after the grapes planted there!) a mix of clay, marls, sands, limestones are found as they are overlying the Cardona and Antognola formations. One of them, Giuanìn, presents a more calcareous-predominant character as it is over the Pietra da Cantoni Formation, with a topsoil derived from calcareous-sandy marls and marly limestones. In the easternmost vineyards (Zio Luigi and Magrina), gypsum can also be found among the silty clay and clayey marls as these topsoils originated from the Complesso caotico della Valle Versa. All this diversity contributes to the complexity of La Casaccia’s wines.

(The Sant’Agata Fossili Formation widely found in Casalese Monferrato and the Monferrato area composed of marls and clayey marls is not present in La Casaccia’s vineyards surrounding Cella Monte.)

Geological references:

Dela Pierre, F., Piana, F., Fioraso, G., Boano, P., Bicchi, E., Forno, M. G., & Ruffini, R. (2003).

Carta Geologica d’Italia alla scala 1: 50.000, Foglio 157 “Trino” e note illustrative. APAT, Agenzia per la Protezione dell’Ambiente e per i Servizi Tecnici. Dipartimento Difesa del Suolo, Roma.

Festa, A., Codegone, G. (2013). Geological map of the External Ligurian Units in western Monferrato (Tertiary Piedmont Basin, NW Italy). Journal of Maps, 9(1), 84-97.

Gelati, R., Gnaccolini, M. (1982). Evoluzione tettonico-sedimentaria della zona limite tra Alpi ed Appennini tra l’inizio dell’Oligocene ed il Miocene medio. Memorie della Società Geologica Italiana, 24, 183-191.

Piana, F., Fioraso, G., Irace, A., Mosca, P., d’Atri, A., Barale, L., Falleti, P., Monegato, G., Morelli, M., Tallone, S., Vigna, G.B. (2017). Geology of Piemonte region (NW Italy, Alps–Apennines interference zone). Journal of Maps, 13(2), 395-405.