Pedro Mendez

This website contains no AI-generated text or images.

All writing and photography are original works by Ted Vance.

Short Summary

Cousin of local viticultural legend, Rodrigo Méndez, Pedro Méndez wears two hats with full-time work in his family’s vineyards and their restaurant during the summer. Located in the Val do Salnés subzone of Galicia’s Rías Baixas, he has medium-aged vines and pre-phylloxera Albariño vines that are nearly two-hundred years old that look more like trees. These ancient plants fill his full-bodied Albariños with structure and a pure citrusy, salty, minerally, high acidity power that only Albariño possesses. He also makes a compelling range of red wines with Mencía and Caíño.Full Length Story

Spain’s Michelin-starred restaurant count is just short of two hundred and fifty, with thirteen holding three stars. And while its total is only a little more than a third of France’s and more than half of Japan’s, it still has more than the US, despite having only 15% of the population of The States. Germany and Italy are the only other countries to have more than Spain, and both have many millions more people.

Michelin-starred restaurants haven’t always been a big deal for Spain (after all, it’s a French concept), but one Catalan trailblazing restaurant that’s now a museum, elBulli, led by the Ferran and Albert Adrià, changed the face of Spain’s global restaurant position and was the first one fully committed dive into molecular gastronomy, worldwide. While Michelin-starred restaurants don’t have much pull in the US over the market’s fine wine interests, they remain the primary measuring stick for Spain’s growers and their achievements. Real estate on lists for these limited-seat restaurants is hard to get (except for wines with built-in investment value), especially with Spain’s embrace of international wines more than most other major European wine-producing countries. To make the cut, you must already have the world’s attention, or you must be doing something unique and at a high level. Pedro Méndez doesn’t yet have the world’s attention, but he’s well represented in Spain’s top culinary destinations, including dozens of Michelin-starred spots throughout the country, including País Vasco’s three-star Arzak, an institution that landed its first star in 1974.

Pedro’s breakthrough into Spain’s top spots started with his reds—50-70-year-old Mencía and Caíño Tinto vines, with the former a peculiar variety for the appellation, especially with its enviable vine age. With just over 1000 bottles produced of each of the two reds, more than half of them are sold to Spanish Michelin-starred restaurants, and most of the rest to top local restaurants. This says something, no? We’re lucky to import a quarter of Pedro’s production of reds along with a quarter of his micro-production, ancient-vine Albariños. It’s not much wine, but we’ll take them.

I understand Pedro’s wines’ place in Michelin restaurants. Both red and white perform extraordinarily well with more time open (one micro-dose of oxygen every ten or fifteen minutes makes them sing after an hour), but the reds glide with light textures with unique finesse and balance of mineral, metal, tea notes, soft fruits, and salivating salty oceanic freshness. After a few hours, they’re gorgeously refined and attractive. On the second day, they feel like they’re still on their first hour. They’re also an adventure for most of us into the unknown.

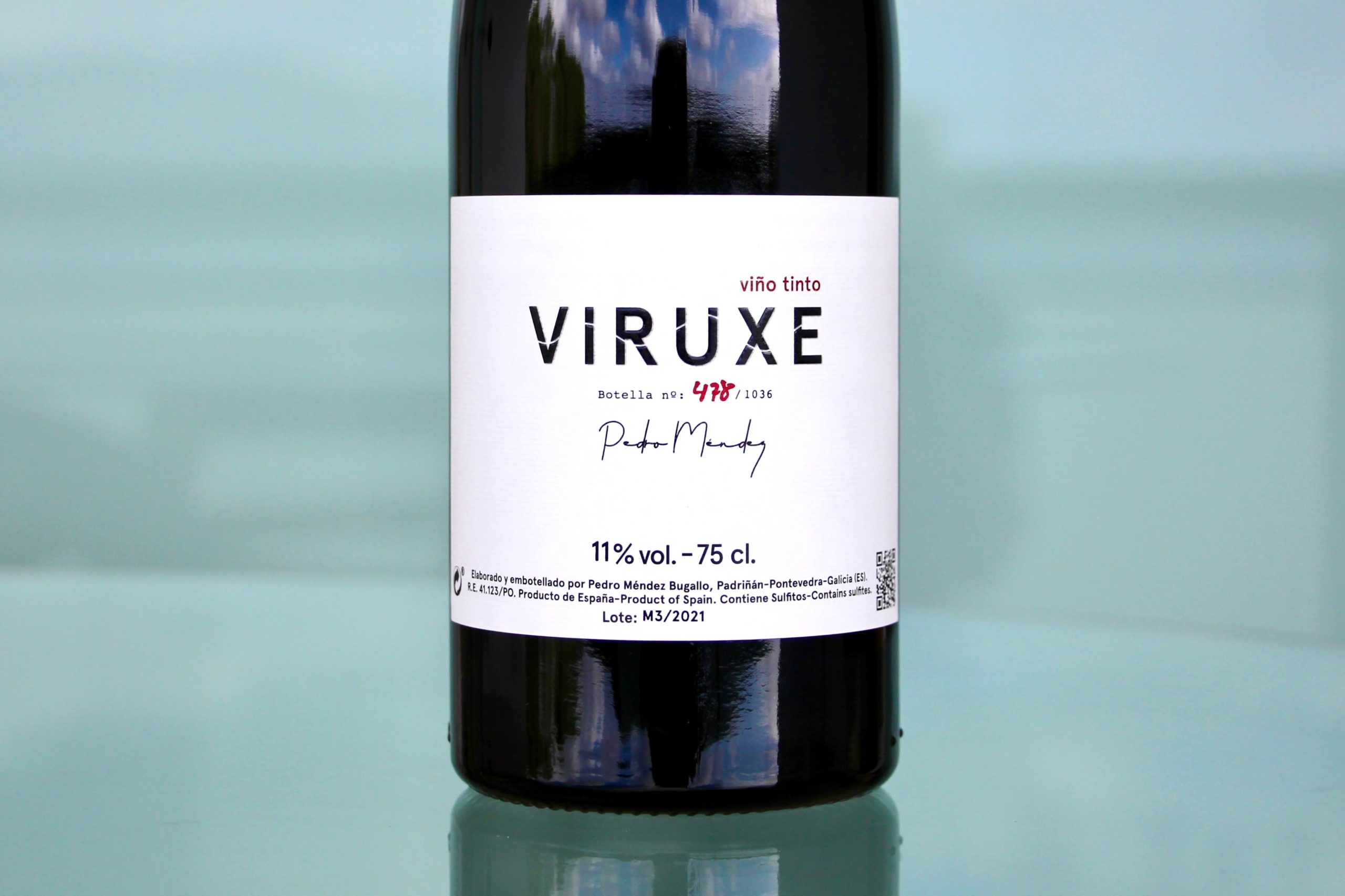

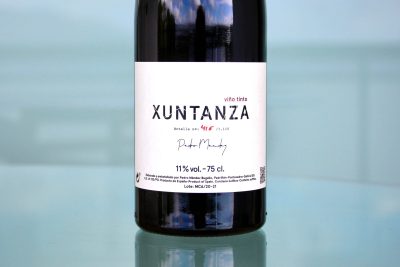

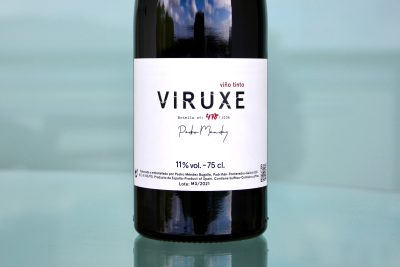

The aromatically powerful and classic Galician Atlantic red, Viruxe is entirely Mencía from a single vintage, while the more refined but edgy Xuntanza, is a blend of Mencía and Caíño Tinto, from two vintages… I never thought a still wine blend of two different vintages would interest me, let alone result in such a compelling wine. But it did, and I’m more than ok with it. It’s the wine’s magic. Both come from a granite sand vineyard in Meaño four kilometers from the ocean. Both are whole-bunch fermented for 20 days in steel and aged nine months in old barrels. Neither are fined or filtered.

On first taste, the Viruxe delivers classic Rías Baixas red wine aromas of chestnut, austere red fruits, pomegranate, sour cherry, bay leaf, and pungent mineral and metal notes. Because of its strong natural snap, I wouldn’t guess it to be 100% Mencía in a blind tasting. (I admit I struggle with Mencía, though Pedro’s is like a ray of light for me. I find a lot of the top examples overrated. In places like Ribeira Sacra, for example, most other indigenous/historic varieties, or combinations of them, would make a more compelling wine on the same dirt. However, there are a lot of great old-vine Mencía around that should live out their days of production before replanting.)

Viruxe, which means “fresh wind,” is aromatically intense but deceptive, as the palate delivers the variety’s naturally gentle touch. Equally gulpable as it is intellectually stimulating, Viruxe alone presents a compelling argument for Mencía as a reasonable Rías Baixas red grape alternative to some of the more aggressive reds of the commune. It lacks naturally high acidity and is usually acidified or blended with other grapes endowed with massive acidity, like Caíño. But here it doesn’t need the unnatural boost or the blend, especially when harvested from such old vines grown on granite and a finishing alcohol of 11%. In Rías Baixas, this is perhaps the least ornery and easiest, pleasure-filled, aromatic and serious red I’ve had from Salnés. Indeed, others deliver a worthwhile experience and are extremely well made, like those of Manuel Moldes, but few are so inviting and gentle as Pedro’s. In a side-by-side two-day comparison next to Xuntanza, it doesn’t evolve as much with time open but after more than a half hour of micro-pours, it finds its footing and lifts off.

Probably like you, I haven’t put much serious contemplation into mixed-vintage still wines, nor have I wanted to. But Pedro’s choice was clever because the result is a beautiful Salnés Valley red. I’m starting to notice mixed-vintage blends more now, but perhaps they’ve been around more than I thought. Xuntanza, meaning “union,” is a blend of equal parts Caíño Tinto and Mencía. Initially, it shares the same aromatic profile as Viruxe, except that it’s mellower and less effusive, more analog if Viruxe is a little more digital. The palate is more stern and tense (Caíño effect) but finishes with salivating mineral strength in the front palate and a suave back palate despite its Caíño-charged acidity. Like many wines with upfront acidity, the first glass seems like a different wine than the second. Its aromatic austerity softens quickly and makes way for more spice, orange peel, pomegranate, and rhubarb. With each swirl flows more delicate aromas while the palate continues with sharp textures and a slight sting but finishes gently. Half an hour in, it softens and begins to ripple like a crystal-clear lake disturbed by the first drops of rain.

Pedro’s Albariño collection is from the Salnés Valley hamlet, Meaño. If I were to draw a comparison to Pedro’s wines and our other growers in Rías Baixas, I’d say they’re more powerful than those of Manuel Moldes and, perhaps of equal power to Xesteiriña, but are more contained and classically styled than the latter. Pedro’s Albariños have broad shoulders, a compact core and megathrust. This may be partly due to the older average vine age of his many parcels, and, in some cases, deeper topsoil. Moldes’ cru Albariños are on schist, with his Afelio on the mostly granite. Xesteiriña harvests from a single plot of extremely hard metamorphic rock with almost no topsoil. The bedrock is somewhere between medium- to high-grade metamorphic rock: some looks like gneiss while others look like schist. Xesteiriña’s rock type is probably the rarest of all in Salnés with vineyards planted.

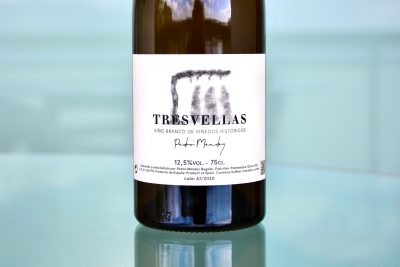

Each of Pedro’s cuvées are staggered releases based on their more optimal drinking window. The eponymous label, “Pedro Mendez,” is the earliest, along with the previous season’s As Abeleiras, and the year before that one, Tresvellas. None of Pedro’s wines conform to the appellation Rías Baixas, therefore none bear the vintage date or grape name (though coded at the bottom as a Lot). These two non-conforming label elements are common in Galicia.

Formerly labeled as Sen Etiqueta, the Pedro Mendez “Viño Branco do Val” (Albariño) lays down the gauntlet as the first wine to taste in the three together. It’s so delicious on the first take, that it’s hard to want to move on. It reminds me of Arnaud Lambert’s Saumur “Midi” with its power over your ability to restrain and drink slowly. It captures the elegance of sandy granite soils, salty ocean breeze rim, sweet Meyer lemon, sweetened juicy lime, honeysuckle, and agave—like a wine margherita (my Achilles’ heel of cocktails, which I rarely partake in nowadays). Forget the oysters and jump straight into salty clams, sweet Santa Barbara ridgeback prawns, and spiny lobster. Though dry, the sweet elements and effusive aromas bring great lift to this fluid and undeniably delicious wine. It’s a firecracker of a starter.

The As Abeleiras “Viño branco de parcela” (Albariño) is released a year after the entry-level Albariño and comes from a single parcela planted in 1993 by a very young Pedro and his father. It sits at 100 meters altitude, also on granite soil. While the 2019 version was raised in steel, this year spent time in old French oak barrels. (2020 wasn’t up to Pedro’s standard, so it wasn’t bottled alone.) While the other two Albariños have a broad band of expressions and roundness due to the diversity of the many vineyard parcels in each wine, this single vineyard’s uniqueness offers a more vertical than horizontal experience. While the other two would be great for a bigger party of people because they jump into the mosh pit and start knocking people out on the first swing, As Abeleiras is initially more snug and better suited for a two-person tango. While the others are wonderful in their way, this is the thinker, the wine to observe and admire for its singularity, focused austerity, and tight, chalky and grippy texture. It’s a minerally beam of light. The others are mineral bombs.

I first tasted Tresvellas “Viño Branco de Viñedos Históricos” (Albariño) in Pedro’s arctic-cold cellar on a rainy and freezing November day. It was almost impossible to warm up and to break the ice shell on the wine. Cold Albariño, no matter how good, doesn’t pair well with a runny nose, numb face, and icy fingers and toes. But in the comfort of my apartment overlooking the Lima Valley on a sunny winterish day in March, it’s different; I’m different. This wine is a gorgeous beast! And when you see the vines it springs from, you know the description is apt. They’re small trees! Their average age is well over a hundred years, and you feel it in the wine. With concentration, depth, and restraint, the warm and well-worked Tresvellas (Three Old Ladies) fills the glass. All the varietal’s classic high-toned lemony notes went to full preserves: sweet, salty, acidic, zest oil and the right amount of bitter pith. The color is between straw and gold leaf, and it tastes expensive.

Pedro Mendez

Pedro Mendez