Bien de Altura

This website contains no AI-generated text or images.

All writing and photography are original works by Ted Vance.

Short Summary

Raised by his mother and grandmother, Carmelo inherited from them a big heart, warmth and charm, along with the inner-city energy and hustle of Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, an industrial port scrunched between the sleeping volcano and Atlantic crammed with half a million locals and four million tourists each year. He returned home in 2017 to begin Bien de Altura after traveling the world working in cellars and vineyards. Listán Negro is the dominant grape in Carmelo’s range, and results in more elegant wines with a fresher fruit profile. In this arid climate with an average annual rainfall of only 134 cm (5.3 inches) and at some of the wine world’s highest altitudes, from 1,100-1,460 meters (3,600-4,800 feet), on mostly east-facing sites on extremely steep orange volcanic sand, silt, clay, and rocky topsoil, he crafts a series of wines with a global cult following. The cellar practices are intendedly low tech and made with minimal sulfites, whole bunch fermentations, extended macerations and neutral aging vessels.Full Length Story

Gran Canaria is one of seven islands in a volcanic archipelago off the coast of Africa (directly west of southern Morocco and north of Western Sahara) created by what started as constant underwater eruptions that developed into islands from the continued tectonic separation along the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. Africa and South America broke apart and continue to move further away on the Atlantic side by about two to three centimeters per year. Gran Canaria is almost right in the center of the archipelago, between the two desert islands to the east, Fuerteventura and Lanzarote, and the islands to the west that become more tropical the further away from Africa they get, like Tenerife and Las Palmas.

On a topographical map of the islands, it’s easy to see that the southern side of each island is more desert-like and the northern part is greener, except Fuerteventura and Lanzarote, both deserts devoid of almost anything naturally green. Precipitation on each island is pretty sparse with (from east to west) Lazarote recording about 110mm (5.3 inches) per year; Fuerteventura 105mm (4.1 inches); Gran Canaria 134mm (5.3 inches), Tenerife, with a lot of variability depending on location, like the big spread between Santa Cruz de Tenerife at around 214mm (8.4 inches) and San Cristóbal de la Laguna at 557mm (21.9 inches); La Gomera 235mm (9.3 inches), El Hierro 170mm (6.7 inches), and finally, with the most rainfall and the greenest of the islands, La Palma with 324mm (12.8 inches). Generally, it’s not a lot. But because of the high altitude of some of the volcanoes, water is well-preserved on the northern exposures and also in good positions for viticulture in these desert/subtropical islands.

Temperature is also a major factor, and not surprisingly the altitude of each plays a major part. Among the main wine-producing islands, Tenerife has the highest peak by a big margin with Mount Teide hitting 3,718 meters (12,198 feet) with peak temperatures in the low 40s Celsius and the lowest recorded temps nearing -10°C. La Palma has the second highest peak with Roque de los Muchachos hitting 2,426m (7,959 feet) with the peak temps hitting the low 40s and the lowest at -3.7°C in January 2021. Gran Canaria is the third highest island with Pico de las Nieves (Snow Peak) hitting at 1,949 meters (6,394 feet) with peak temps in the mid-forties with the lowest also -3.7°C in January 2021 while Carmelo was pruning at around 1300m altitude. Lanzarote, the most desert-like viticultural island peaks at 671m (2,201 feet) at Peñas del Chache, with a high in the low mid-forties Celsius and its lowest recorded temperature of 8°C. All the islands with higher peaks will naturally have the lowest temperatures in certain spots during the winter.

Gran Canaria is a circular island with extreme desert on the south side and a pocket of tropical green (though still more desert than tropical) on the north side. Gran Canaria is not as famous for wine growing compared to Tenerife, but Carmelo is changing that.

Raised by his mother and grandmother, Juana and Lola, respectively, Carmelo inherited from them a big heart, warmth and charm, and the streets of Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, the inner-city energy and hustle of this island’s industrial port scrunched between the quiet volcano and Atlantic crammed with half a million locals and four million tourists each year into its one-hundred square kilometers (~38 square miles).

Carmelo returned home to Gran Canaria to begin Bien de Altura after traveling the world, including harvests in the southern hemisphere and a finish of his “practical” studies with the Portuguese wine luminary, Dirk Niepoort. At Niepoort, he befriended Dirk’s right-hand man, our very own Luis Candido da Silva, the toiler and mind behind Quinta da Carolina. It was also the beginning of El3mento, a project started by Luís and Carmelo which has now expanded to include close friends in Chile and Switzerland. Immediately Carmelo turned heads with his own-rooted vineyard wines that expressed the same bright and generous personality of their maker and the Listán Negro grape.

Listán Negro is the dominant grape on the island and in Carmelo’s wines. Listán Negro results in more elegant wines with a fresher fruit profile, while another famous Canary Islands grape, Listán Prieto (País), at least when compared to Listán Negro, produces a more robust, deeply complex, and fuller wine. (Side note: In Chile’s Itata Valley, País (Listán Prieto) grown on volcanic soil is much more elegant than those minerally and more rustic versions grown on Itata’s granitic soils.) The key to keeping both varieties aromatically pure and gentle on the palate is a vigilant tasting regimen during fermentation to prevent either variety from getting carried away on tannins and reduction before pressing, especially Prieto. However, under Carmelo’s watchful eye, the combination of the Canary Island varieties cofermented and untouched (unless necessary due to imposing reductive elements) during their month-long vinification before pressing usually does the trick. Without a clear idea of the cause, Carmelo often says that the volcanic wines produced in Gran Canaria are less expressive of reductive elements than those of Tenerife, the more famous island with loads of great producers and vines. Carmelo also makes a white from Listán Blanco, more commonly known in Spain as Palomino, but it rarely leaves the island.

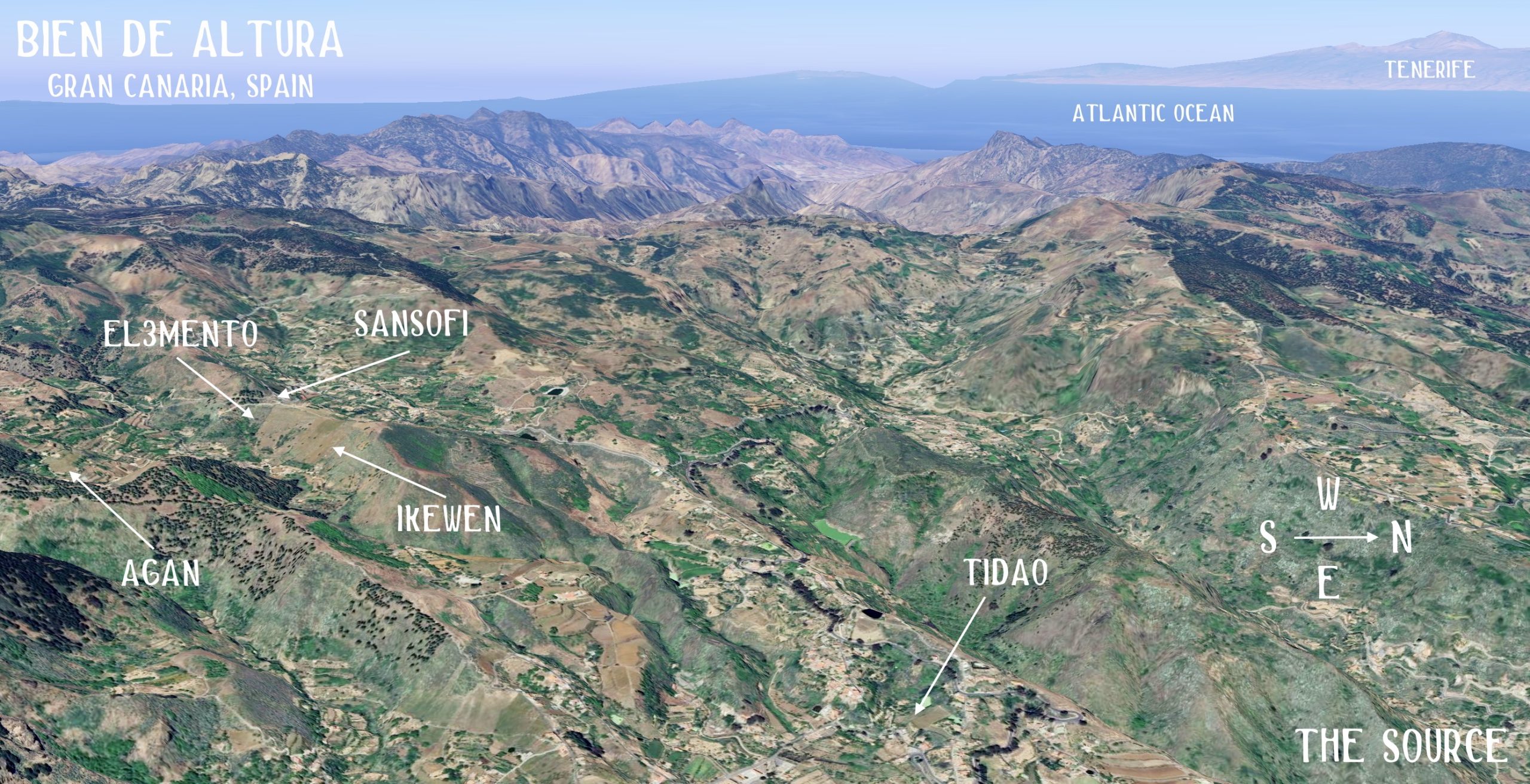

Carmelo focused his initial research on old vines in the higher altitude areas on the northeast side in the center area of the main volcanic cone, about four kilometers from the peak, Pico de las Nieves. Since he started in 2017, he’s amassed more vineyards and continues to seek out new parcels. Today, he makes five different red wines from the island, four from single-vineyard plots. Each parcel is, of course, on volcanic soil, and because there is no known phylloxera on any of the Canary Islands, every vine is own-rooted with what we would call, “indigenous” vines; perhaps “first-known generation” could be more suitable because there were no vines before the arrival of the Spaniards, who supposedly first arrived in the 15th Century after the conquest of the islands. There are historical documents, such as the writings of Pliny the Elder, that the Romans at least knew about the islands, though they may not have inhabited them. The timing of the Spanish invasion of today’s Islas Canarias also coincided with the exploration and settlement of the Americas, where they also planted vines around the same time, with Chile as another unique region (in this case, country!) suitable for quality viticulture void of phylloxera. Chile is also home to perhaps the world’s oldest living vines: País, the same as Listán Prieto.

(Interestingly, many Spaniards from Andalucía populated the Canary Islands whose descendants then populated Chile. This is probably why the Chilean accent and some cultural terms closely match the Canarios.)

Already an iconic label in the natural wine world’s rarities, Ikewen is a name bestowed in honor of the island’s Indigenous Berbers and/or Gaunches peoples, which in both languages means “origin.” Carmelo’s stable of vineyards continues to grow, and what was composed of three different vineyards only a few vintages ago is now taken from seven on the northeast side of the island (like all the parcels) with an average age of forty years with some over one hundred with own-rooted (pie franco, like all the vineyards) 85% Listán Negro (the elegant Listán) and 15% of other rare “first-known generation” varieties. The altitude ranges from 1,100-1,460 meters (3,600-4,800 feet) on mostly east-facing sites on extremely steep orange volcanic sand, silt, clay, and rocky topsoil.

While the single-parcel wines have distinctive personalities and go in a straight line, the parcel blend of Ikewen is the most universal. In smaller doses inside this vineyard ensemble, it hits the highest of the high tones and the lowest of the low tones in the entire range. The fruit profile meanders between pale red and slightly dark red, and its subtlety is supported by a more dynamic structure. All the wines are interesting and complex, but the combination of all seven parcels makes it particularly special. It’s by far his highest production wine but it may remain the most compelling simply because of its completeness and balance.

Once harvested, the whole-bunch fruit for Ikewen is fermented for five weeks in steel without any intended extractions: only a gentle pressing of the cap a dozen centimeters down by hand to keep it from building bacteria or volatile acidity in the upper and more exposed area of must/wine. After a gentle final pressing, it’s aged for a year in 85% steel and 15% in 225-500L old French oak and is neither fined nor filtered before bottling.

Three of the single-site wines, Tidao, Agan, and Sansofi, are all vinified for a five-week, whole-bunch fermentation/maceration in open-top 500L French oak barrels, followed by aging one year in 225-500L old French oak. Like Ikewen, they are neither fined nor filtered.

Often the most tantalizing and charming, sour red candy, red flower red in the range, Tidao comes from an own-rooted, 120-year-old single parcel (2024) on the northeast side of Gran Canaria planted with 70% Listán Negro and 30% of the reds, Tintilla, Listán Prieto (País) and Vijariego, and the whites Listán Blanco and Malvasia on a moderately steep undulating slope facing southeast at 1050-1070m on volcanic scree (breccia) bedrock with clay and silt topsoil. Important note: it’s a beauty and completely gulpable, so be careful with your company to ensure everyone is measured, and of the sharing type.

Agan, with its more solemn black and white label, is as compelling as any in Carmelo’s range. It’s often the most reserved upon opening, expressing more savory than sweet notes, with white pepper and delicate fruits that build with time. It’s a fine wine built on structure and subtlety and comes from a single parcel planted ninety years ago (2024) to 85% Listán Negro and 15% Listán Prieto, Listán Blanco & Malvasia on a medium-steep slope facing northeast at 1350-1370m. It’s just across the small ravine that separates the parcels for El3mento, Sansofi and a good portion of vines for Ikewen. Here, the volcanic bedrock is covered with loose, small volcanic rock (called picón), sand, clay, and silty red topsoil.

If Tidao is Carmelo’s ethereal charm, Agan his contemplation, Ikewen his balance, then Sansofi is his ideal; it has the best of each in his range found here but within a tighter framework. A ninety-year-old parcel (2024) planted to 85% Listán Negro and 15% Listán Prieto and Listán Blanco between the El3mento parcel and Ikewen vines on a medium-steep slope facing north at 1330-1365m on volcanic bedrock with picón, sand, clay, and silty red topsoil, this is the unique wine in the range that faces due north. Like Agan, Sansofi needs more time to open than Tidao and Ikewen—again, it’s best to share with fewer people.

Carmelo’s tribal wine, El3mento is also an outlier in style. Often led by bright floral notes and earth, it was aged for eight months in a 1000L amphora with the whole clusters, remaining unmoved with only the free-run wine kept for the final wine. It’s composed entirely of Listán Negro planted forty years ago (as of 2024) on an extremely steep slope adjacent to Sansofi but on the other side of the hill facing southeast (Sansofi, north). It shares the same volcanic picón, sand, clay, and silty red topsoil as the other wines, but with higher large volcanic rock content. El3mento is a project developed by Carmelo and Luís Candido da Silva, who met while at Niepoort in Portugal’s Douro Valley. Today, this project has extended to Switzerland and Chile’s Itata Valley, where these friends make their wines the same way, with long whole-cluster, post-fermentation macerations in amphora.