Aseginolaza & Leunda

Photography and writing by Ted Vance.

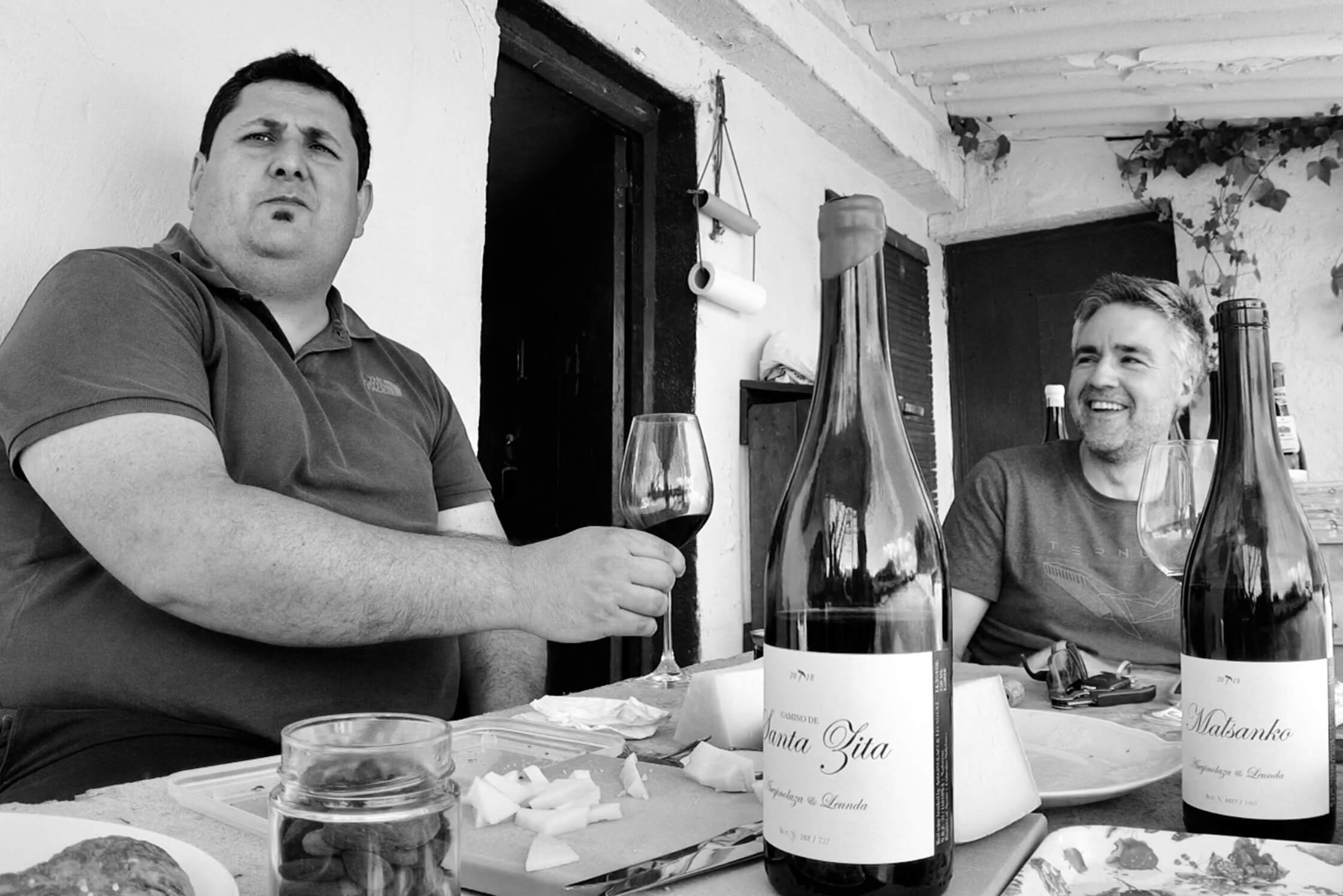

Environmental biologists and former winemaking hobbyists, Jon Aseginolaza and Pedro M. Leunda, have directed their full attention to a project focused on a better understanding of Spain’s Navarra, a historical wine region with a severe identity crisis stemming from its living in the shadow of Rioja, Spain’s historical crown jewel. Always the bride’s maid and never a bride, the region began to focus on international varieties in an attempt to stand out and increase its market share but lost a significant piece of their historical identity in the process.

Moving in the opposite direction of this trend, Jon and Pedro are focused on finding and recovering old vineyards planted with indigenous ancient vines (mostly Garnacha/Grenache, the historic grape of the region) inside of zones with a greater biodiversity—all potential assets for this region that gives them a solid answer of sustainability in its own unique voice in contrast to the widely monocultural vineyard landscape of much of Rioja. Their old-vine vineyards are mostly planted in high-altitude sites on variations of calcareous sandstone bedrock, sandstone and clay, all naturally farmed, with wild, aromatic plants left to grow freely, even between the rows of vines.

Pedro and Jon launched onto the scene with their 2018 vintage, with results so compelling they were immediately noticed in all corners of Spain, including in the wine press and many of the country’s Michelin-starred restaurants. When asked why they chose the harder path of Navarra instead of Rioja, they responded, “We did not choose Navarra, Navarra chose us.” They are both from the coastal Basque Country but moved to Navarra to study and work, and there they entered the world of wine. They think that where they are in Navarra, which is mostly in the north, has a lot of similarities to the fresh Rioja they like. They have the same latitude, altitude, and limestone, “mixed with old Garnacha vines, it’s a perfect cocktail for us.”

First Contact: A Surprising Nostalgia

Even more than Rioja, I was skeptical about jumping into Navarra, given the region’s dominant style of wines we generally don’t gravitate toward: bigger, with unbalanced alcohol, too much extraction, and often the terroir-numbing effect of new oak with many international varieties planted—you know the type. Navarra wasn’t even on my radar until a Spanish importer-distributor friend in Basque country with similar taste to mine pointed me in the direction of Jon and Pedro.

I stared at my sample bottles for weeks in preparation to taste them (actually more to slowly unhinge my mind from my prejudgments), with the hope that they would be as good as their sleek and classy labels. Once open, many showed strong dark colors with streaks of red fruit and woody perennial dark herbs and backcountry smells reminiscent of my most formative wine years. Vivid memories of my earliest vineyard pilgrimages came to mind, driving through the hilly, windy, black backroads of Napa and Sonoma with the windows down and the heater cranked after a big winter rain storm, my head half outside the window and my lungs filling with deep wafts of cold, thick forest air dense with aromas of moss, mushroom, and crowded conifers and oaks, their damp and darkened crowns draped with wraith-like lace lichen. (I was weaned on California’s legendary old wines at the start of my relentless career pursuit and made many trips there from where I lived in Arizona at the time. I suppose people may be hard pressed to believe, what with our roster of European wines and their particular style that appears to share almost nothing in common with California’s historical wines of that time, that I greatly miss drinking them. If you’ve had the old wines from California’s hungry years—before the area was overrun with the wealthy in search of their name on a bottle from this prestigious area—back when makers first sought to prove themselves on the world’s stage and are still in good shape, then you probably understand the style I’m referring to. The last twenty-five years have been a different story…) More than the nostalgia of California wine trail smells, and even some tastes of those glorious old mountain Cabernets and Merlots of that time, what first attracted me to Jon and Pedro’s wines the way I was to those old Cali wines, was their authenticity.

Jon and Pedro’s wines genuinely express Navarrian Garnacha’s duality of dense yet lifted aromatic components that resemble the multitude of interesting flora indigenous to their area, the most easily noticed being wild thyme, rosemary, and lavender. The thyme in these parts is particularly amazing stuff; so aromatic, it’s like a hybrid with lavender, and during my first visit with Jon and Pedro they were flowering and I’ve never smelled anything in nature so perfect as blooming thyme growing in the vineyard sourced for their red wine labeled, Otsaka. It can be very desert-like in some areas of Navarra (and quite densely forested in other parts), as well as through much of northern Spain south of the Cantabrian Mountains, until you reach the Galician Massif in the far west. But the landscape is littered with a multitude of salvaje aromatic plants that seem to infuse into the wines. More classical garrigue aromas also found in the French countryside seem to have influence, including resinous plants and trees found in these more arid places close to the Pyrenees and all around the Spanish and French Mediterranean coastline. Once these oil and resin molecules pass by in the wind, or are transported bit by bit by insects to the grape clusters, they seem to meld with the wines, creating delightful savory nuances.

This Spanish countryside is so clearly reflected in Jon and Pedro’s wines and they raise them in neutral aging vessels to highlight its influence (they use stainless steel and used French oak barrels and concrete will come soon, too). I love to cook and their wines are best with full flavored food: deeply-flavored cassoulet containing some confit duck, the herbs turned black after half a day of slow cooking, the crust pressed down into the fat every hour (at least six times!), the beans, the lamb, the confit pork belly, the sausages until that utterly savory, fatty, dense, rich aroma generated by the alchemy of slow cooking fills the air. The woodfire grill? A perfect match. Salt, herbs, and fresh garlic dry-rubbed into Black pork; grilled ribs with only salt, Spanish jamon, chorizo, dry-aged Galician beef with its intoxicating, profound flavor and delicious yellow fat developed from its life in the fields (instead of a grain trough) infused with the same herbs they graze on in the Spanish mountains and high desert near Galicia, which is home to Chef Gordón and his temple of beef, El Capricho, and his wines, which we also import under the Bodegas Gordón label.

I’m a Hemingway fan, and long before the international grapes arrived, Garnacha wines made in the past, probably like those from Aseginolaza & Leunda today, surely supplied liquid cultural inspiration for the young writer in Navarra’s capital, Pamplona, as he penned The Sun Also Rises; and on his fishing expeditions in the Pyrenees cooking over open fire under a star-pocked sky. Jon and Pedro’s wines filled with savory earthy goodness are made for cold nights and fire, for conversation and contemplation, for communion with nature, all accompanied by the quiet crackle of the flame.

Environmentalists First, Winemakers Second

Environmentalists see vineyards differently, and Navarra needs guys like Jon and Pedro—the entire wine world needs more guys like these two. Their upcoming ripple effect in this region seems imminent, not only as winegrowers but as conservationists and beacons for a more natural and respectful way with a global ecological vantage point that many winegrowers don’t possess.

Jon and Pedro met in high school in Donostia/San Sebastian, and then went to study Biology at the University of Navarra, in Iruña/Pamplona. (The dual city names are Basque and Spanish, respectively.) Jon furthered his studies in Agricultural Technical Engineering, and Pedro obtained a PhD in Environmental Biology, specializing in Fish Biology. Both had jobs in their chosen industries prior to making their first wines together in 2016, which was only three barrels, followed by more in 2017 for commercialization. Their Spanish coming out party was the 2018 vintage. Believe it or not, 2016 was the first year that either of them had ever made a wine; clearly they picked it up very quickly. However, during all their years as wine lovers before that they had soaked up a lot of ideas by visiting wineries and asking a lot of questions. Most wineries in Spain, especially new ones, have enologists to ensure their work doesn’t go off path, but they don’t. They do it all, and their results in just the last few years are impressive and extremely promising.

While they aren’t certified in organic farming, each of their vineyards illustrate their respect for nature, with many plants still growing in the middle of their vineyards (not only grasses, but also some rather firmly rooted bushes!). They don’t use any vineyard treatments outside of copper and sulfur—so, no herbicides, pesticides, systemics or otherwise. They’re all natural.

Wine Style

With regard to their wine style, Jon and Pedro are trying to repair Navarra’s wheel, not reinvent it. They strive for fresh wines that are sharp, clean, light bodied, not oaky (hence the absence of any new oak barrels in their cellar—thank you very much!) and express the varietal characteristics and the terroirs they’ve come from. They believe it will take them a while to find the right balance of ripeness and lower alcohol levels. To simply pick earlier doesn’t exactly help them achieve what they want; first comes understanding how each specific terroir functions. This takes time and a different management of each vine than in the past where in some sites controlling alcohol content wasn’t of importance. The vines (and the local growers with whom they work) have to be trained differently and these are the things that will take the longest. We must remember that until these boys showed up, it was usually “the bigger, the better,” and that’s what a lot of people wanted and expected with “special wines” from this area, a region inclined to shout to get attention instead of singing softly. “Personally, we do not like high alcohol wines and have been in the pursuit of lowering the alcohol of ours through different growing techniques since the beginning. Our first wines were 14.5–15%, but progressively less by working for greater precision with harvest timing and prior vineyard work as we gain knowledge from vintage to vintage on the characteristics of each plot. We think we will be able to make high quality Garnacha in the 13–13.5% range.” Sign me up!

Garnacha: Greatness Almost Forgotten?

Garnacha is one of the world’s greatest grapes. From a complexity potential standpoint, it can duke it out with the best, and with a variety of different soil and rock types that yield extraordinary results: Châteauneuf-du-Pape and its satellite appellations grown on limestone bedrock and clay; the grape’s newest darling region in Spain, Gredos, Garnacha grown on granite at very high altitudes; the gray schists of France’s Collioure; licorella (black slate) of Priorat; and of course, in Rioja and Navarra, on calcareous sedimentary soils. It also shows its talent for diversified wine styles as the grape most responsible for France’s rosé production, all the way to fortified wines of the country’s Rousillon, with Banyuls and Rivesaltes as two of the historical highlights. It’s no accident that Château Rayas is composed almost entirely of Grenache (perhaps even 100%, but no one really knows exactly except Emmanuel Reynaud, its owner and vigneron…) and it may be one of the greatest wine experiences to be had in this life if you can find an old one—better know a collector with a lot of cash and in need of more drinking company! Once Châteauneuf-du-Pape and many of these places right the ship on alcohol level, get ready all you lower-alcohol wine drinkers! It will be a great thing for the world of wine, and for all of our livers.

It’s not only Tempranillo that invaded Navarra and took surface area away from Garnacha, which in the 1970s, accounted for 90% of its surface area, as it was the region’s most historically important variety. But according to Decanter magazine (2014 publication), there are 11,500 hectares under vine in the region with 91% of them red: Tempranillo 34%, Garnacha 23%, Cabernet Sauvignon 16%, Merlot 14%, Graciano & Mazuelo (Cariñena, or Carignan in French) less than 2%, Syrah & Pinot Noir less than 1%. On whites: 9%: Chardonnay 5%, Viura 2%, Garnacha Blanca, Malvasia & Sauvignon Blanc less than 2%. Garnacha is down about 75% from where it was in the past and it will take years—perhaps even generations—for it to regain its crown in Navarra. Jon and Pedro are optimistic, but most importantly, they are committed to extolling Garnacha’s virtues in their wines.

Measuring Stick: Tempranillo and Garnacha

We don’t need to talk about the Cabernet Sauvignon and Merlot in Navarra. They’re there, and we can continue to ignore them like we have Bordeaux for so many years now—just kidding, Bordeaux! For the record, I have no qualms about Bordeaux making a comeback, and I hope they do. Bordeaux has historically demonstrated—almost effortlessly—an unmatched consistency within the still wine world for its ability to age and improve over great lengths of time. It’s undoubtedly one of the greatest wines on earth. It’s just that it went through (and is probably still going through) a tough phase for some wine drinkers with a physical and mental aversion to most of those produced in the last decades with too much overripeness, over extraction, and new oak. I think that in Bordeaux’s past the new oak levels may have been similarly high as the last decades, but when grapes are riper the wood is often more pronounced in the wine’s expression, at least in my general experience. Navarra’s gravitation to these varieties seems to be a result of trying to separate themselves from Rioja and to veer away from historical varieties into the international style of European wines, similar to those of the very successful Italian IGT. However, it never materialized in Navarra the way it did in Italy. Moving on…

Why is Tempranillo so dominant in Spain? And does it really thrive well in Navarra, or was it there because of the popularity of Navarra’s western neighbor? On the second question, Jon and Pedro take the position that the only fair grape trade out on Garnacha was Tempranillo. They love the grape, but their focus remains Garnacha. What follows is a brief breakdown between the two varieties by Jon and Pedro through the lens of their Navarra vineyards (which may have different results elsewhere depending on each parcel’s soil type, genetic material, exposure, slope gradient, etc) and in conjunction with a research paper of Gombau et al. (2020) (reference below): 1) Despite Garnacha being known for bleaching color with more direct exposure to the sun, in these parts it’s a blacker berry, and Tempranillo is a black and blue berry; 2) Garnacha’s skin is thinner but the grape larger; 3) Garnacha’s buds burst earlier; 4) Garnacha flowers slightly earlier; 5) Tempranillo sprints to ripeness after flowering jumping ahead on veraison about three weeks ahead of Garnacha; 6) Garnacha is picked more or less two weeks later than Tempranillo, hence the Spanish root word for the grape, temprano, which means “early”; 7) Garnacha has smaller seeds and berries than Tempranillo; 8) The pH levels of Garnacha wines at the same sugar levels of a Tempranillo wine is significantly lower, however, a wine made from only the juice of both (no skins or stems) share a similarly low pH level; 9) The titratable acidity (commonly called total acidity) levels when picked around the same alcohol potential are nearly the same with only a slight favorability to Garnacha.

To throw a few ideas toward the first question regarding Tempranillo’s dominance in north-central Spain’s more arid zones, first we can say that it is more reliable and predictable than Garnacha. Its later bud burst than Garnacaha means it has a lower risk of frost damage—very important in today’s frost-crazy times! Later flowering than Garnacha is beneficial against mildew and stronger winds that often happen earlier in the season. Earlier ripening means less potential damage in the latest parts of the season with fresher, cleaner fruit when picked as well, which means less loss to disease and losses from sorting in the vineyard and then in the cellar. Let’s face it, productivity means profitability, and Tempranillo is one of those grapes that can create a tremendous wine without suffering as other varieties need to in order to achieve their heights. Perhaps the Bordelais who focused on Rioja in the 1800s were intrigued by the variety’s accessibility compared to Garnacha too, and set up camp in Tempranillo’s historical zones of Rioja Alta and Rioja Alavesa instead of further away from Haro. Tempranillo’s acidity is present but not dominant, which means more quaffability and charm in a less edgy way, similar to Bordeaux. If the French believed that the epicenter of their stylistic preferences was closer to Logroño, they probably would’ve set up shop there instead of Haro. While these are only a few considerations about Tempranillo’s relatively rapid expansion inside of Rioja and further into Navarra (among many very important regions to the west, most famously Ribero del Duero), there are surely greater historical reasons than these points, if not much more accurate to the story. However, I suppose the most important feature of Tempranillo is that it has the potential to make some of the world’s greatest wines, and who doesn’t want that potential?

In Navarra, Garnacha is a very rustic variety, adaptable from warm to cool environmental conditions and able to withstand longer periods of drought, therefore it was the choice for poor, rocky soils. In warm conditions, Garnacha tends to reach high alcohol levels, but in cooler terroirs while managed properly produces well-balanced aromatic wines. Otherwise, Tempranillo is more sensitive to drought and high-temperature conditions, so it requires cooler terroirs (or terroirs with a deeper topsoil, like much of Ribera del Duero, generally on flatter land but often at very high altitudes). In Navarra, Tempranillo is planted mainly in the warmer and dryer southern subregions close to Rioja Oriental and is almost always dependent on irrigation in that area, whereas further into the hills there is less of a need to do so. Garnacha is more resistant than Tempranillo to vine diseases, but it is very prone to coulure (grape shatter), so its productivity varies greatly from year to year. Jon and Pedro have some small, non-irrigated Tempranillo plots in cool terroirs in the Tierra Estella subregion, just next to Rioja.

Architect, weekend winegrower, and hobby historian, Javier Arizcuren, one of our producers based out of Rioja Oriental, explains (with the support of verifiable historical documents) that public records in 1973 show that Garnacha was the majority grape in Rioja at 39% of the vine surface area; now it’s less than 8%. Tempranillo maintained about 33% of the vine surface area at the time, but dominated the vine surface area of San Vicente, in Rioja Alta, at around 76%. Garnacha’s supreme reign in Rioja spanned from the mid-nineteenth century until the 1980s. Prior to that Mazuelo (Cariñena/Carignan) was the most dominant grape in Rioja until the arrival of powdery and downey mildews, and phylloxera, in the mid-1800s. Javier says that in the 1980s, more industrial companies began to demand more fruit from the growers, prompting them to uproot much of the old-vine Garnacha and replant with the more prolific Tempranillo, whose stronghold was in the far western end of Rioja. Naturally, this trend spilled over into Navarra.

Tempranillo versus Garnacha is a battle of heavyweight players that carry different strengths and shortcomings. Garnacha’s Achilles’ heel is that its seeds take a longer time to ripen with relation to its overall phenolic maturity (and potential alcohol content) than many other varieties. Therefore, it’s difficult for it to achieve stratospheric complexity with alcohol levels below 13%, like many of the world’s great varieties with a similarly high dose of tannins and acidity, like Italy’s Aglianico (Taurasi, Vulture) and Nebbiolo (Barolo, Barbaresco, and Alto Piemonte) wines. Both grapes are fabulous and with seemingly limitless complexity and aging potential. But in the spirit and borrowed wisdom of our good Italian friend from the Barolo and Barbaresco regions, Tino Colla, whose family has three-hundred years of grape-growing experience, “To know the right thing to do in the future we must look at the past. The growers were wiser and more connected to nature than we are today and made decisions only by observation for what is best suited for each place. We have to consider this history before we do anything.” Tempranillo’s historical kingdom lies further west. Garnacha is Navarra’s former glory, and that is where Jon and Pedro have set their course.

Side Commentary: The Old Vine Issue

The stable of old vines in Europe is holding on pretty well but climate change is up to no good, and these old timers may come to an earlier end than they should. With the trend of lower alcohol wines dominating the fine wine restaurant division, these historically important vines present a problem. They produce powerful wines with bigger flavors and deeper textures, and big-time complexity (all positive things), but with higher alcohol. The impact of excessive heat on old vines can especially be felt in warmer Continental climate areas, away from the ocean; take France’s Beaujolais, Southern Rhône, and even recently in the Côte d’Or, where the latter has three vintages in a row (2018-2020, and 2017 would’ve been in that mix if it hadn’t had a cooler first half of the season) with riper flavors due to the sun’s increasing potency on the Earth’s surface, and mostly higher alcohol levels atypical for this region. Beaujolais can be a behemoth these days when old vines are involved, a sort of roided out and dense but still graceful caricature that glides gently but smacks you upside the head with a strong buzz by the third glass. Old vines display awesome quality and depth with which younger vines have a hard time competing, and there’s some kind of maturity and balanced wisdom within their layers, imparted by their old age and deep roots; but to get them to still produce their magic without the following morning’s cranial vice grip is hard. Jon and Pedro are committed to finding the solution of less alcohol but without a loss of great complexity—a hard task with Garnacha.

(Read more about this topic with a short article I wrote a couple of years ago that goes deeper on this topic of old vines and their resulting higher alcohols levels at https://thesourceimports.com/beaujolais-in-context/)

Rioja and Navarra: Siblings on different trajectories

Luck has as much, if not more, to do with success (also lack of success) than talent. Indeed, one must put in the work for success, but simply to have opportunity is an immeasurable advantage that is all too often overlooked.

Look at a map and you will see that the D.O.s of Rioja and Navarra are not only joined at the hip but the shoulder too. When comparing each appellation’s climate, relative topography, and with a broad brushstroke on overall terroir, there are more similarities than differences. First, let’s explore a short history of the recent political differences and eventually the great fortune of one while the other struggled, the general separation of these conjoined siblings.

In the Middle Ages, some areas of today’s La Rioja, particularly Rioja Alavesa and San Vicente de la Sonsierra area (two major zones with some of Rioja’s most talented terroirs, the latter in the western parts of Rioja Alta), were under the rule of the Navarra Kingdom, which at the time was called Sonsierra Navarra. Only around one hundred and fifty years ago began the story of one region’s lucky streaks and in parallel, the other one’s less fortunate circumstances. First there was the fungus duo of powdery mildew and downey mildew, and the famous louse, phylloxera, all of which arrived in Europe in the 1800s. France was first to be ravaged by these scourges with Bordeaux being crushed in the early rounds before it spread out from there. The French Bordelais needed answers to keep their thriving international wine trade alive and they looked south to Spain for sustenance until solutions were found and eventually incorporated.

In the mid-to-late 1800s, the wine regions of Rioja and Navarra began to economically grow apart with the construction of the Tudela-Bilbao train line that ran right through Haro, today’s heart of historical Rioja bodegas in Rioja Alta and Rioja Alavesa. Of course, that train line ran through much of the southern part of Navarra as well, but today’s Navarra subregions to the north at a greater distance from the railroad were disadvantaged. Haro’s historic train station, located on the far western end of Rioja Alta (and only a kilometer away from the border of one section of Rioja Alavesa), was the starting point where French winegrowers set up camp during the onset of the vineyard problems. Many of the growers and négociants from Bordeaux brought along with them their knowledge of crafting world-class wines. The French invested big in the area about the time the railroad was installed, a rail that ran from one end of Northern Spain to the other, but most importantly, it linked the rail system to France. The influence the French would have on western Rioja started a momentum that Navarra could not keep up with.

Interestingly, the political separation of the wine regions of Rioja and Navarra is only about a hundred years old. To protect its wines against counterfeits from outside of Rioja, its designation of origin was officially recognized in 1925 and excluded almost all of Navarra. The designation of origin for Navarra was approved in 1933, but its first regulations were not approved until 1967—they had missed the train yet again. The separate designations of Rioja and Navarra may have been a combination of the perception of quality, along with geographical factors. However, Rioja’s D.O. goes beyond the administrative region of La Rioja. The Ebro River geographically separates them historically and administratively today as well, while some of Navarra’s land on the north side of the river (left bank) remains part of the Rioja Oriental subregion (formerly called Rioja Baja), the furthest east of the three subregions of Rioja.

Terroir Overview

What’s most important to us is not the political separations and perhaps even the history, but rather the terroir and what it imparts to its wines. Political and cultural advantages and disadvantages along with time have put things in place as they are today, but terroir, from a general sense, was in place long before the influence of humans. And while humans alter terroirs simply through their first act of planting vines followed by the needed management afterward, many terroir elements—some of the time—remain authentic. We know these elements influence wine, no matter how much is altered or guided gently with a greater respect to nature’s rhythms naturally, and others less concerned about nature’s way. The producers we gravitate toward are those who respect the nature involved in their terroirs and want them to thrive as much as their grape production, which, to us, includes the surroundings of their vineyards. A visit to Jon and Pedro’s vines easily demonstrates that these ideals are intact.

Terroir Part One: The Climate

It’s true that seasons can start out perfectly and end tragically, while others with a dismal start can end up the vintage of a lifetime. The summer sun of this region is a given, but it’s Navarra’s wind that greatly influences the weather around the fruit ripening phase and the last month before harvest, a vintage’s most crucial moment.

Wind is always an influential factor and Navarra is at a confluence of currents, and it’s cold when it comes from the northeast or northwest. The northwesterly wind, called Cierzo, blows through the Ebro Valley with dry, cool air favorable for long ripening and creates an environment for healthy grape clusters. It also influences the day and nighttime temperatures in a more positive way with a greater swing between the highs and lows. The northeasterly wind from the Pyrenees is the problem wind, usually bringing more rain and imposing the opposite effect of Cierzo with a greater mildew pressure, resulting in the need for more treatments and ultimately more production losses. Usually at the end of September southern winds dominate with hot weather from Iberia’s interior. This means faster ripening but also dangerous storms that can create chaos and cause problems in the vineyards with a sudden downpour of rain or hail that can cause flash flooding.

Terroir Part Two: Geology

The geological setting of Navarra and Rioja could be distilled down to the fact that it is mostly sedimentary rocks ranging between limestones, marls, sandstones, and shales with a huge spectrum of rocks with different compositions, grain sizes (clay, silt, sand gravel, etc.) and formed in different environments than the surrounding mountains. However, the geological story is worth a deeper exploration if you are interested in northern Spain and southwest and southern France. And given the lack of useful in-depth information on Navarra, a greater research for a more extensive report was made. Co-authored and co-researched by Ivan Rodriguez, our in-house MSc Geologist and PhD student at the University of Vigo, the report includes Rioja because we find that it’s easier to understand these neighboring regions within the context of each other; also because research work on Navarra terroirs and geology is notably absent in comparison to Rioja, and their geological settings are not so different. In it, we cover the macro-terroir components that greatly define the regions (and many neighboring wine regions in both France and Spain), including the Pyrenean and Alpine orogenies, and the Ebro Basin. There is also a quick overview of the subregions of Navarra and Rioja and a deeper dig into the bedrock and topsoil origins of Rioja which have a very close relationship to Navarra’s geological makeup. Included are a few new custom maps we put together to better illustrate the geology and its relation to the subregions. There are also some very cool maps made by others that help illustrate the geological setting. You can read our short essay and see all the very cool maps here.

Navarra Subregions

What follows is a very brief explanation of the setting of their vineyards and the subzones of Navarra. While the region has less coverage today in terms of its distinctions, perhaps down the line things will take on more relevance and specificity within each subzone. There are indeed talented terroirs waiting to be revealed, and we believe that Jon and Pedro will be at the forefront with other progressive growers in this regional renaissance.

Navarra is cut up into five main subregions: Ribera Baja, the furthest south, Ribera Alta in the middle toward the north, and closer to the Pyrenees Mountains forming a rim from west to east, are Tierra Estella, Valdizarbe, and Baja Montaña. Three of Navarra’s subregions, Tierra Estella, Ribera Alta and Ribera Baja, border the Rioja subregion, Rioja Oriental, and you won’t find much difference from a general sense between them until you move further away from the Ebro River and into the hills inside each region. Much of this landscape is close to the river and produces innocuous, serviceable Tempranillo and Garnacha wines without a great sense of character. They are grown on flatter areas formerly a large basin once filled with a massive lake but more recently a flood plain for the Ebro River with deep, loamy topsoils and very little contact with a definitive bedrock.

The limestone-rich northern subregions are Jon and Pedro’s focus, and it’s in these hilly areas where the greater differences can be found between wines due to terroir elements like bedrock, topsoil, climate, and natural biodiversity. Here, the rockier terrain and cooler climate (for the region) opens up the possibilities to make compelling wines with lower alcohol, despite that the vintages at the beginning of their project weren’t exactly low-alcohol years. They explain that the general characteristics of the wines from Tierra Estella (including their plots in Dicastillo) are more earthy than the garrigue-rich wines of Baja Montaña (with vineyards in San Martin de Unx), and the wines from Ribera Alta (around sites in Olite) are generally fruitier. But more than the subregions, it’s about the parcels—usually the case with small-lot, grower-producer wines.

Aseginolaza & Leunda Vineyards

Navarra is expansive and Jon and Pedro cover a lot of ground. Their thirteen vineyard parcels (as of 2021) amount to six hectares in total and are scattered approximately 35 kilometers east to west and 50 kilometers north to south with vineyard altitudes ranging between 370m and 655m. The picking time from the start of the season to the last picked fruit of the same variety, Garnacha, can be more than a month’s window; in 2021, it was thirty-six days from start to finish.

Harvest usually starts in the second week of September, but it depends on the production of each vineyard. As Garnacha is usually irregular in production, they start with vineyards containing fewer grapes that naturally ripen earlier. They also consider the pH levels of the grapes in order to maintain the higher acidity and the freshness they want in their wines.

Altitude has a lot to do with the ripening of each vineyard, and theirs range from Montejurra Mountain, at a height of 655m, down to their lowest, in Azagra, at 380m. They believe there is great potential in many small old-vine Grenache vineyards that will complement their overall stylistic preference, and because it’s the northern limit of the appellation where freshness is more present in the climate, and this is apparent in their wines.

Azagra (380m altitude) is their southernmost vineyard area (technically a part of Rioja Oriental as well as Navarra), faces northeast, and has a lot of gypsum in the soil. The grape variety, location, exposition, and soil give the wines produced from this vineyard a cooler profile than expected in these parts. These vines in Olite (410m) are similar to Azagra, but the difference between them is the age and the management of the vines. The bedrock here is composed of white limestone with 50cm of topsoil with a lot of rock mixed with clay. Like all other sites with elevated levels of active calcium in the soil, they have to be careful not to plow too much or too early after the winter before the soil temperature has elevated enough, because the lime becomes very active and toxifies the vines with chlorosis (a blockage of the root systems that inhibits uptake of essential elements, like iron), which make them produce less chlorophyll so that the leaves easily die under the region’s intense heat.

In the north, their vines in Barasoain (535m), San Martin de Unx (540m), Artazu (440m), and Muruzabal (445m) are almost in the cultivation limit for Garnacha to fully ripen. The topsoil in these areas are clayey-loam soils (clay mixed with a smaller proportion of sand) with a lot of limestone rock on limestone bedrock. Under the influence of Montejurra Mountain, are the vineyards in Distingo (655m), Dicastillo (490m), Allo (430m), and Arellano (440m), all on the southern slope of the mountain but at different altitudes and similar geological origins of the Montejurra conglomerates. Not surprisingly, the rockier sites are found in the higher altitude vineyards (Arellano), and more clay-rich sites are at the lowest altitude vineyards in Allo.

Red Wine Production Overview

The red wine processing is a pretty straightforward, low-tech, simple approach. Garnacha, like the other principal red grapes of the region, has fangs if its tannins aren’t managed. While it has smaller seeds and fewer of them than Tempranillo, they can still pack a punch, and their thicker skins are already laced with bigger tannin potential, so crushing the seeds too much—especially if they are more green than brown—can be a bad move. Because of Garnacha’s potential for big tannins, the fermentations in their cellar are usually in the short to medium length, with 10-20 days of fermentation and whole cluster usage that ranges between 20%-100%, depending on the season and the parcels. Extractions (punchdowns, pumpovers) are limited to one short session per day to not overdo it or relegate great supportive material for complexities (especially those further down the line of bottle aging) to the compost pile. They use a basket press which gives them confidence that their press wine is gentle enough to be included in the final blend. They always use old French oak barrels (never new ones) to respect the aromas and character of Garnacha, and can be as short as a couple of months and as long as ten—all decided by taste rather than a predetermined formula. Sulfur additions are made during processing of the fruit and again at bottling. Sulfur levels range between 30-60 mg/L (30-60ppm), but are most often around 50.

The White Wine

The only white wine from their range (as of 2022) is the Txuria. Grown at an altitude of 490m on the calcareous-rich loam of Dicastillo, it’s composed entirely of Viura (the same grape that makes up 90% of the blend of Lopez de Heredia’s epic white Riojas). It’s got more than twenty different synonyms, but Viura is probably best known outside of Spain by its French version, Macabeo. A relatively neutral grape variety on the fruit side, it leaves a great opening to be a “clean” channeler for interesting vineyard terroirs and the textures they often impart to their wines. That said, if the terroir is not interesting, the wine should be the same; if it’s a great terroir, well, the potential for greatness should follow—as far as Viura wine is concerned! Jon and Pedro’s interpretation is framed by its fermentation at low temperatures (to improve its fruit expression, an often lacking element of this variety) and aged in stainless steel for four months followed by another four months in old 400-liter French oak barrels. The wine could be described as bright, vertical, and salty, and appears to be capable of a long haul, despite its short élevage.

The Red Wines

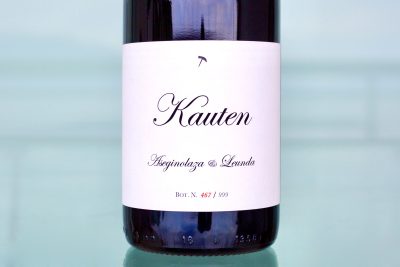

Kicking off with their entry-level red, Kauten is made entirely of Garnacha from Olite. Grown on limestone bedrock with a shallow topsoil, the vineyard sits at 410m and is aromatically the brightest and lightest in color, leaning more toward a crimson red, this is the most playful of their wines. Not to be taken too seriously, while at the same time not letting its complexities go unnoticed, the vigor of its young vines bring on its upfront appeal, and the 25% stem-inclusion was a solid stylistic choice to soften its wonderfully aromatic, taut red berry punch. If Kauten represents the spring and early summer berry fruits, Matsanko (75% Garnacha, 15% Tempranillo, and 10% Viura), located in Dicastillo and grown at 490m on a direct south face, shows early spring sugar plums (perhaps influenced by the little bit of Tempranillo) balanced with exotic green notes. It comes from old bush-trained vines, which is noticeable in the wine’s expansive palate. While plums are mostly harvested in the summer, the overall appeal of this wine is one for the autumn.

In the middle range, from Dicastillo and Allo at 430-490m on a south face, Cuvée (88% Garnacha and 12% Tempranillo) is a lightly extracted ruby red, subtly woven with a lovely high-toned red fruit; it still remains more firmly planted in the savory realm than the fruity—perfect for food. Almost marked by its surroundings of wild aromatic herbs (known as garrigue, in French) and a delicate orange blossom note, the Cuvée las Santas (100% Garnacha) is composed of all the single-vineyard plots that in years don’t yield enough fruit to make into individual bottlings—including Camino de laTorraza and Camino de Santa Zita. Grown in four different spots on limestone soils at altitudes between 440-540m, is only slightly stouter and spends a few more months in old oak barrels than does Cuvée. It’s a deeper scarlet, sanguine red, and carries a welcome gentle amargura to balance its glycerol mouthfeel of its old-vine fruit. If time isn’t available, a slow-pour decantation will surely speed up to full reveal.

All their wines are in a very limited production, and some of them have minuscule quantities, especially their single-site wines. Camino de Santa Zita comes from a single plot in San Martín de Unx facing northwest on limestone bedrock with limestone rock-rich loamy topsoil. It’s pure, old-vine Garnacha aged in stainless steel for four months followed by nine months in old French oak barrels. This wine was the star in my first interaction with their lineup of wines. Camino de la Torraza, has an equally broad depth and ever-evolving layers. An equal blend of old-vine Garnacha and Cariñana, it’s grown in their lowest altitude vineyard in Azagra at 380m, facing east. Both Camino de laTorraza and Camino de Santa Zita are rich in flavor of the Spanish countryside. These top wines show the potential of this new beacon of Navarra’s future.

Aseginolaza & Leunda’s savory wines capture the essence of the Navarra and will always be best with food. Imagine these wines on a rustic Spanish wood table next to a vineyard eating jamon de bellota and chorizo with a wood fire readied for Galician beef chuleton (ribeye) or some black Iberian pig cuts with gorgeous marbling of fat, and dark red meat, like the cuts la presa, el secreto, and la pluma. On their second day open, these wines (when young) often become even redder in fruit tone than day one, and even more surprisingly gentler on the palate—so promising!

Reference: Gombau, J., Pons‐Mercadé, P., Conde, M., Asbiro, L., Pascual, O., Gómez‐Alonso, S., … & Zamora, F. (2020). Influence of grape seeds on wine composition and astringency of Tempranillo, Garnacha, Merlot and Cabernet Sauvignon wines. Food Science & Nutrition, 8(7), 3442-3455.