Cantina Madonna delle Grazie

This website contains no AI-generated text or images.

All writing and photography are original works by Ted Vance.

Short Summary

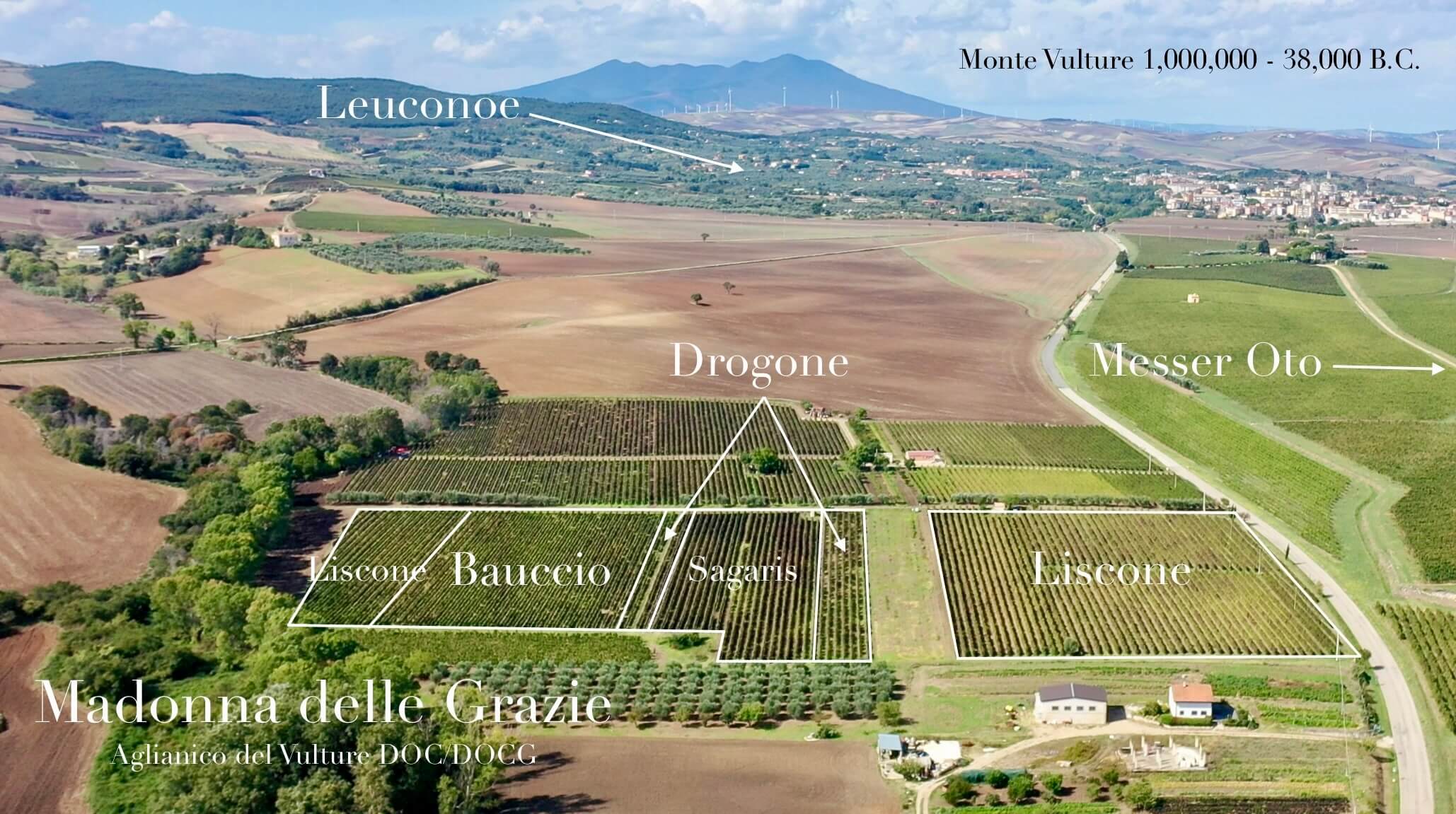

The two idealistic enologists and brothers Paolo and Michele Latoracca infused with their father Guiseppe’s deep vineyard experience results in a perfect combination for authentic, organically farmed, volcanic Aglianico wines. Located in Venosa, one of fifteen communes of the DOC and DOCG areas of Aglianico del Vulture, their terroirs are between 400-550 meters altitude. Between their three parcels, there are five notable terroirs independently bottled.Full Length Story

The historical Roman town Venosa, named after the Roman goddess, Venus, sits in the northwestern corner of the Basilicata, Italy’s third least populated department. The city’s centro storico is mostly well-manicured, or at least somewhat recently renovated, and the large and often juxtaposed limestone and black volcanic road slabs seem to be even polished in some areas; it’s not typical of Italy’s south, where inside cities spatzzatura (Italian for trash) always seems to be within sight. There is an industrial side to Venosa, but where you want to be, in the historical center, is wonderful. What makes Venosa even more special for us is our relationship with the Latoracca family, the owners of Cantina Madonna della Grazie, a name derived from the eponymous historic church that abuts their home and cantina.

The Family

During our year in Salerno, about two hours away by car from Venosa, we went back and forth to visit the Latoraccas, particularly the highly energetic and sweet-natured, Paolo. He’s the family’s principal winemaker, and would sometimes make the trip down to visit us on some weekends, too. He and the eldest brother, Michele, are an enormous wealth of historical and technical information. They both have enology degrees from universities, and Michele maintains an additional degree in agronomy and was a contract professor of enology for the University of Basilicata between 2011-2014. Both also have a great interest in their local history and are like walking textbooks on the subject.

Their father, Giuseppe, born in 1940, is quiet and calm. At seventy-nine (as of 2019), he’s still very active and works everyday in the vineyards, but bears the physical signs of a life of labor in the fields—his hands are curled in like the talons of an eagle. He’s the family’s wise one, having absorbed generations of knowhow. He and his father are responsible for planting and maintaining the family’s historic vineyard collection planted exclusively to ancient massal selections—vine cuttings of unique, hierloom biotypes. Because of their work, few can boast the old age and genetic value of the Latoracca vineyards. (More on that later.)

Immacolata (Irma), mamma for short, couldn’t be more different than her husband, Giuseppe. Like Paolo, she’s exuberant, full of laughter and with that classic excited about life Italian volume. One day in the cellar I observed her methodically and quietly labeling and capsuling wine orders; hand labeling is done with all of their wines, even the entry-level bottles. As I might have for anyone walking in on that moment, she reminded me of my mom with her commitment to doing whatever needs to be done. Gianfranco, the middle son, lives in Canada, and works as an architect. He designed their labels, all of which somehow impeccably match the spirit of each cuvée: a reverence for the past, the mood of each wine and a classy, modern take on the relatively new history of the cantina.

The Wines

The Romans founded Venosa in 291 B.C., and it’s not surprising that they wanted set up camp here. Thanks to its geological architect, Monte Vulture, the land promises great agricultural diversity. Anything from apples and stone fruit groves, figs that are surely the best I’ve ever had in Italy (though the ones I speak of came from organically farmed trees next to the Latoracca’s house), cereals, nuts, berries, livestock and, of course, underappreciated, world-class vineyards. The climate is dry with little rainfall compared to most of Italy, but areas rich in deep volcanic clay beds can hold the water and are good for a variety of agricultural products. The more balanced clay-based soils with good drainage are left for the vine.

The majority of the Latoracca’s vineyards are inside Venosa, one of fifteen communes of the DOC and DOCG areas of Aglianico del Vulture. It’s one of the most favorable areas for high quality grape production and also the biggest commune. Both Michele and Paolo stress that making generalizations here is tough due to how change is quick from one site to the next. However, altitude seems to be a reliable indicator concerning the growth cycle. Their vineyards are in the middle altitude zone, between 400-550 meters and phenolic ripeness is more influenced by temperature here than exposure (because they all have good exposure); the higher in altitude the slower the ripeness—a universal truth in grape growing. For example, at altitudes near 700 meters, there can be around ten to fourteen days difference in ripening time from that in Venosa at around 400-450 meters.

The Latoracca’s principal vineyard, Liscone, is home to their top three Aglianico del Vulture wines: Liscone DOC, Bauccio DOC and Drogone DOCG, all grown within rows of each other, the Drogone flanked by the other two. Black to dark brown volcanic clay soil dominates, with varying levels of topsoil depth and soil grain composition of stones, sand and clay (with more detailed information to be found on their wine pages). The first wine from the vineyards, bottled as “Liscone,” displays a dark nighttime Chagall-esque dreamscape that somehow captures perfectly the wine’s characteristic calm and cold earthy characteristics. The soil is a mix of dark/black clay and coarse sand from the blondish-gray, extremely friable tuff (lithified volcanic pyroclastic debris), giving the soil a slightly lighter shade of blackish grey. There are uncountable variations of different structures of tuff, depending on the volcano, each specific eruption and each individual deposition. Bauccio has less tuff, and the soil is darker and deeper before the tuff bedrock further below the surface, making for a wine with a more substantial body and material from the start. Drogone, what I consider the most compelling of the range, is made in only special years where the season allows for this micro-parcel to ripen very late; thus far, they’ve bottled only 2003, ‘04 ‘07, ‘09, ’13 and ‘15. Located between the Liscone wine parcels and Bauccio, the balance of the soils is between the two: deep, black clay and a medium depth of topsoil before the tuff bedrock.

What makes Drogone special is certainly the vine age (planted around 1960), but equally important its genetic makeup. It’s a unique massal selection of Aglianico with more compact cluster and more red than black tinted grapes. The deciding factor each year if Drogone is produced at all is whether or not this unique, late-ripening ancient cultivar achieves the extra-phenolic maturity to properly ripen the seeds. With the extended fermentation maceration that typically last 40-45 days, the seeds must be absolutely perfect, or the tannins will be ever so slightly coarse. It really has nothing to do with the quality of the vintage, but only if the seeds can reach maturity in that last week on the vine.

The Latoracca’s Aglianico red wine line starting point is Messer Oto, a more red-fruited than black Aglianico del Vulture. The site is like a roller-coaster slope, with a big dip in the center and uptick on the other side. Principally grown on sedimentary soils from vines planted in 2002 and grafted using the chip-bud grafting technique in 2003 with buds from the Liscone’s massal selections. This is their summertime Aglianico (yes, there actually is such a thing), with its red fruit and friendly nature makes it easy to enjoy on a warm barbeque day. There is also a rosé and white, both made from Aglianico obtained from their highest vineyards (500-560m) grown on soil richer in calcareous clay. (There’s a lot to say about the white, and it can be found on the product page.)

Attack of the Clones

Vine age and genetic material in Vulture are things to consider and pursue with growers in the area. Between 1970 and 1990 the quantity of operational vineyards was greatly reduced due to a lack of migrant workers, most of whom had moved to Italy’s industrial centers in the north and to other countries. This abandonment was followed by the failure of many cooperatives and cantinas, including some of the top-flight historic municipalities, like Barile, Rionero and Maschito. Michele suggested that by the end of the 1990s, more than 80% of Aglianico del Vulture was centralized in Venosa. After the arrival of new producers starting in 1997, this pattern started to turn around.

The attack of the clones began at the end of the 1970s when the administration of the municipality of Venosa planted 120 hectares of Aglianico in the municipal land and rented them to farmers. Given the lack of propagation materials from the local nurseries, those that were replanted during this time, and especially in the 1990s, were in part clonal selections oriented toward quantity rather than quality. Michele (who supplied me with most of this historical context), suspects that between eighty and ninety percent of all vineyards in the Aglianico del Vulture DOC/DOCG area that were planted in the 90s are clones, and many of them were quite different, with larger berries than the historic and local Aglianico del Vulture biotypes.

Old vines in Vulture are a rarity compared to many of the world’s greatest wine regions. The desire to have more productive young vineyards during the new boon and the decades leading up to it drove growers to over-crop so they could sell more grapes to the local co-ops. This cut short the lifespan of many of the historic vines of the Aglianico del Vulture biotype, which were then replaced with more productive clones. Michele suspects that for vineyards fifty years or older planted with local massal selections make up well below ten percent of the appellation’s vine surface area. The good news for the Latoraccas is that all of their vineyards, including the young Messer Oto, are massal selections from their Liscone vineyard.

In the 2000s, with some thanks to the economic support of the EU, new vineyards were planted in Vulture and more research delved into its massal selections and development with clones from the Aglianico biotypes. This sparked a backlash against the planting of clones originating outside of the area. Most of the newer plantations were henceforth either clones of the Vulture biotype, or its massal selections.

As is often the case, the new producers pouring into the area got started by purchasing a winery first and buying grapes from other growers to produce, then using their profits to gradually acquire vineyards. Before the ‘90s, there were around fifteen local producers; by the 2010s there were more than fifty. Madonna della Grazie was at the same time newcomers—now as winemakers, as well as one of the region’s most historic family of growers with a treasure trove of old-vine, massal selections.

2003 is the first year the Latoraccas bottled wine from their vineyards after almost a century of exclusively selling grapes. From the start, armed with their two young scientists and their father’s vineyard, they quickly found success with high quality wines. Their top wines are unique due to their focus on a specific and special plot of Liscone. And now they’re in search of other terroirs within the appellation to expand their vineyard collection.

Aglianico and Nebbiolo

Aglianico is often compared to Nebbiolo, and this comparison is not a stretch. In Ian D’Agata’s book, Italy’s Native Wine Grape Terroirs, he makes a compelling case as he matches aromatic compounds found in both grapes that are linked by sensory perception. However, Michele, who did extensive research on the Aglianico for a university, explained that one large difference between them is the color and the amount of polyphenolic compounds. This is due to Aglianico having more epidermal layers (skin) than most red grapes out there and many more than Nebbiolo, but also its specific anthocyanin composition (learn more about Aglianico’s anthocyanins here), the main component that makes up the color of the wine. This explains why Nebbiolo’s natural color tends to be quite light by comparison, especially when the wines are young. Of course, with a lot of time in the cellar aging in wood, Aglianico will lighten up in color and find more hues close to Nebbiolo, but almost always with more deep color.

Perhaps another compelling argument for their similarities is that Aglianico from Taurasi are largely grown on calcareous bedrock (of course, some have volcanic topsoil deposits derived from various eruptions most likely from Campania), like those from Piemonte’s Langhe wine region, home to Barbaresco and Barolo. Vulture Aglianico grown mainly on volcanic soil and Nebbiolo wines on limestone—as Barolo and Barbaresco are—demonstrate that the similarities are less clear, at least in their youth. Perhaps it’s the calcareous origin of much of the bedrock and soil of Taurasi that brings a stronger connection to Aglianico and Nebbiolo from the Langhe. The common misconception that Taurasi is principally a “volcanic terroir” may encourage people to lump it together with Vulture. It might be that Barolo and Barbaresco have more in common with Taurasi in their dynamic shape and power (a typical consequence of limestone soils) than a Nebbiolo-based wine from Piedmont’s Langhe wine area and Aglianico del Vulture.

For a year I lived in Salerno, a port city in Southern Italy close to the Amalfi Coast. And never far from my mind was Monte Vesuvio, the notorious volcano that famously buried Pompeii and Herculaneum in its ash and pyroclastic flow only a couple of millennia ago. Pliny the Younger (the nephew and adopted son of Pliny the Elder, who died in this catastrophic event while trying to rescue people) described in letters to friends a horrific scene, impossible to imagine if you weren’t there. Interestingly, an even bigger eruption in 1631 killed over 3,000 people. It’s most recent was not too long ago, in 1944. (Watch the video here.) Every trip into Naples for a pizza or to catch a plane brought thoughts that maybe today would be the day…

The Violent History of Monte Vulture

Volcanoes are violent. And the most powerful can change an entire landscape in hours. Consider Washington State’s Mount Saint Helens that erupted in 1980. Take a look at a Google earth map (link) that shows with great clarity what happens when 1,300 feet of mountaintop gets blown off of a near 10,000-foot peak. There are numerous videos that show what happened with the flooding and pyroclastic flows that devastated an entire region. (Here’s one) Even as far as five hundred miles away where I grew up in Montana, the daytime sky was black and it rained ash for days.

Monte Vulture was one of Italy’s most brutal volcanoes and, thankfully for humankind, its last party ended about 140,000 years ago. Several eruptions that geologists know of preceded the last, which brought the mother load of destruction on the area and the volcano itself. In the last event, it literally flipped its lid and devastated the already terrorized landscape around it. Once the massive magma chamber exhausted itself, it collapsed and gave shape to today’s inner sanctuary of nearly tropical-like nature inside and around the mountain, with the two side-by-side, mirror-like Monticchio lakes inside the remaining caldera. (Take a look at it on 3-D.)

Monte Vulture’s seven peaks surround the sunken caldera and sit like a crown. During the volcano’s rein, the pattern was a continued series of eruption, flooding, eruption, flooding, eruption and finally, collapse. Between the tens of thousands of years between eruptions, alluvium of various sedimentary deposits was brought in by torrent water flows that originated from the nearby Apennine Mountains to the west. Lacustrine (from lakes) and marine (from the sea) calcareous sediments created a sort of stratigraphic layer cake of conglomerate depositions and volcanic debris flows of magma, tuff and other pyroclastic materials. It should also be noted that not all of the volcanic depositions originated from Monte Vulture; other locations of smaller eruptions took place as far as one hundred kilometers away from the mountain.

Vulture Geological Setting

The geological setting of each area is diverse and difficult to generalize, except that like many wine regions, things can change dramatically from one meter to the next. However, what could be said from a geological standpoint concerning the resulting wines is that each site is important to note based on its unique soil composition and altitude. Even some of the highest altitude vineyards that sit close to 700 meters may still have some non-volcanic alluvial deposition. That said, it could be a reasonable generalization to state that likely more than 75% of the vineyards in the Vulture appellation are on volcanic soils of some sort, while the rest is alluvial and likely to have some volcanic material. It’s a lot like its more famous neighbor, Taurasi, but with an inverse proportion of these two rock/soil types.

Vulture and Taurasi Comparison

Everyone who has any interest in better understanding various terroirs in southern Italy consistently asks—especially of Vulture producers—how Vulture and Taurasi stack up, not only in quality, but in terroir imprint. The answer may be as equally simple as it is complex. I will present some considerations, a touch of opinion, and leave the rest to you. Given how curious I am about this inquiry, we’ll go a bit deep, and it will help to illustrate the more interesting characteristics of Vulture and bring more context to the discussion.

Similarities

First, let’s start with a few similarities of the wine regions: 1) Altitude (which of course doesn’t account for the rare outlier): Vulture 350m-700+m, Taurasi 350m-700+m; 2) Communes: Vulture 15, Taurasi 17; 3) Harvest dates: both depend on altitude, vine age, yield, biotype and more, but they usually start, as of the late 2010s, in mid-October and finish in early November. There are likely more similarities to speak of, but that’s a start. It’s thought that the latest picking areas of Taurasi finish slightly later (like days) after Vulture’s coldest zones.

DOC and DOCG Laws

The differences by law of the two DOCGs are as follows: Taurasi was upgraded from a DOC to DOCG in 1993; Vulture upgraded to DOCG in 2011. Not to state the obvious, but the near twenty year separation between the DOCG upgrades clearly shows that Taurasi carried its tradition forward without as much lost to the past—and in no small part due to the legacy of the Mastroberardino family’s ten generations and Antonio, the family legend that brought them out of the ruin of post-World War II and into Italian wine immortality—Vulture didn’t get it back together until more recently. (This is covered more above in The Story section on this page.)

Taurasi DOCG wines may be blended with other grapes (like Piedirosso or Barbera) and must be at least 85% Aglianico, but most serious cantinas use exclusively Aglianico. In the Aglianico del Vulture region, all DOC and DOCG wines must be 100% Aglianico. As for aging before release, Taurasi is required to be aged in the cellar for three years with a minimum of one of those in wood cask before bottling; Taurasi Riserva aged for four years, with a minimum of one and a half years in wood; Vulture Superiore for at least three years with a minimum of one year in wood and one year in bottle before release; Vulture Superiore Riserva for five years total, with a minimum of two of those years in wood and one year in bottle before release. Clearly both laws uphold the common understanding that serious Aglianico needs a proper and lengthy aging to be worthy of their respective DOCGs and to approach their greatest potential.

It’s in the defining terroir aspects where it becomes a little more challenging to navigate, especially with Campania historically suffering more than many wine regions from too much misinformation concerning its geologic setting, and how heterogeneous it can be. Since geology was already touched on in the first part of this section (Lay of the Land) we’ll start there. But first, I’d like to point out that many old books and articles written by wine journalists on Taurasi appear to be vagulely researched (if researched at all beyond a few cantinas) from a geological standpoint; so I suggest sticking to the most recent material that’s begun to set it straight. Somehow it was either overlooked, not talked about much until recently, or writers simply preferred the sexy and simple narrative of lumping everything into the volcanic arena—like many used to do when speaking of the “granite hill of Hermitage,” which only represents about 15% of the geological setting of that hill.

Another perspective I’ve gained in my years traveling through less-dissected wine regions is that the growers who own the land largely misunderstand the geological setting of their vineyards; but who can blame them, they’re farmers not geologists. (To be clear, I’ m not a geologist, but merely an obsessive, neurotic wine importer with a particular penchant for rock and geology.) I’ve witnessed firsthand while traveling for some years with geologists in Europe that most winegrowers don’t really know what they’ve got from a scientific perspective, not only geologically, but also viticulturally and enologically. The historical knowledge of winegrowing is a millennia of observation applied in a practical way, not so much a technical one.

Volcanic Origins: A Misunderstanding?

Both Taurasi and Vulture can relate to some degree on the volcanic origin of much of their soil and bedrock. However, to claim that Taurasi is a “volcanic wine region” would be like saying that Sancerre is a silex wine region. Of course, specific areas of Sancerre do have a lot of silex (in English we call it chert, or flint), but there are more calcareous marine sediments—limestone. The volcanic elements in Taurasi are often stated to have come from an extinct volcano, but the blanket of volcanic deposits that cover some areas with limestone bedrock may have come from a series of Campanian volcanoes, not just one. According to Paolo Giannandrea, Professor of geology from the University of Basilicata, a local authority on Monte Vulture, believes the culprits are likely Vesuvius, which is not extinct, and/or local eruptive centers. He also states that the Phlegraean fields (a super volcano bordering Naples) and Roccamonfina, to the north can’t yet be ruled out. If one speaks of all seventeen communes of Taurasi, the majority of land is on limestone bedrock while the fifteen communes of Aglianico del Vulture are principally volcanic-derived soil and bedrock.

Exposure is another consideration. Much of Vulture is pretty flat or softly rolling, and with some notable hills (again, fluctuating between 350m-700m) and some medium-sized terraced sites. Taurasi is not really that flat and most of the vineyards are on hillsides and large sloping plateaus. Vulture is largely exposed all day, with the exception of those that sit at the east end of Monte Vulture that may catch its late afternoon shadow, or down inside a small erosional valley carved out by waterways. Taurasi is not as obviously exposed to such an all-day supply of sunshine and one could theorize that more consideration goes into expositions in the area. Exposure interplays with the climatic influence, which is very particular to each site’s exposure and altitude.

The Climate

The average annual temperatures are similar in both areas, though Vulture has slightly cooler winters than Taurasi. But their rates of precipitation pose one considerable difference between them. In Taurasi’s western end, next to Avellino, the average rainfall is 775mm per year, the same as Beaune, in France, or Sonoma, in California. The Taurasi village has 711mm and some higher altitude sites perhaps a little more or less. Venosa, the capital of Vulture, has a meager 532mm, the same as Australia’s Adelaide, or even less than Tunis, in northern Africa. (It’s a good thing that Vulture maintains some water retentive clay soils.) November has the biggest rainfall for both, which may present a challenge for the late-ripening Aglianico, especially in the higher elevation sites, with Taurasi at a slight disadvantage compared to similar altitude sites in Vulture. Each site and its specific microclimate will present a different result. With more variations in Taurasi, some less-exposed or with completely different exposures (unlike Vulture where almost all sites have open exposures), one could theorize that there would be greater disparity between the subregions and specific vineyards in Taurasi than those within Vulture.

Aglianico Biotypes

Biotypes of Aglianico are another level of complication, and one that is difficult to navigate without knowledge of the way they grow—in other words, it’s tough to read between the lines of a young, finished wine, but the way they grow is more easily understood by farmers with experience. There are three main biotypes: Taurasi, Taburno and Vulture; and a few others, plus a bunch of clones. And in summary from Ian D’Agata’s book, Native Wine Grapes of Italy, the Taurasi biotype has small berries and is less vigorous, Taburno has high natural acidity and the biggest bunches, and Vulture’s are medium in size and render wines more fruit driven and elegantly nuanced. The caveat to the biotype and clonal consideration is a massive can of worms because they are no longer contained within one area or another, and are perhaps more messed up in Vulture because of the likely influx of Campanian clones brought there in the 1980s by outsiders setting up shop and replanting older vines with more productive clones. That said, all of the Latoracca family wines are made with are massal selections from old ancient vineyards; they are all original Vulture biotypes. (Read more about this in the section above in The Story, and look for Attack of the Clones.)

Once you feel like you’ve waded through the mess I’ve presented, you may feel like you’ve end up out of the rabbit hole and staring down a cliff with no bottom in sight. Now we must consider each individual estate, their specific terroirs and the choices made: how they work the land, biotype or clone selection, vine age, vineyard culture and treatments, soil amendments (organic, biodynamic and “natural wine” included), picking times, extractions, aging time and vessel makeup and size, filtration, additives, and on and on.

Terroir and the Winegrower Influence

What seems paramount (and simpler) is the individuality of each specific wine and the producer’s philosophy and practice. The reality is that Vulture can taste like Taurasi, and vice versa. Perhaps you could say that outside of Aglianico’s obvious contribution to each wine, a Taurasi grown on limestone may not relate so clearly to a Vulture on volcanic soil. But I’d posit that if you blind-tasted three wines within the parameters of 100% Aglianico, same vintage, biotype, vine age, altitude, ripeness level and made precisely the same in the cellar, the probability of stark distinction could be improved. Take for example, one Taurasi from limestone soils and the other Taurasi from exclusively volcanic soil, and the third wine a Vulture also exclusively from volcanic soil. If the taster were told only that the wines are from either Taurasi or Vulture, but two of them are from one of the two appellations, I’d bet that the resemblance of the two wines from volcanic soils would be more closely linked than the two Taurasi wines from different soils. What do you think?

I admit it’s difficult to say anything definitive from a macro-orientation between these two areas, save the soil. And many of the growers hesitate to state any empirical separation of the two. Perhaps wines with more cellar age will clarify matters, but Vulture’s disadvantage is that it doesn’t have enough solid references—for historical reasons—to make that a fair comparison. All of this complexity is the reason this question brings a grimace to the face of the growers, followed by a look toward the sky for an answer. Most of them know they really can’t say with certainty what the differences are. They’re wise enough to know that there are too many factors to consider, and when you think you’ve got it nailed, a single sip of wine can change the game. -TV

Acknowledgments, Credits and Useful Links

The historical content of this essay is based on the storytelling of the Latoracca family, with some cross-referencing and fact-checking from various literary sources both online and in books, as well as a scientific review by Paolo Giannandrea, Professor of geology from the Università della Basilicata.

Additional materials were obtained from Paolo Giannandrea, Luigi La Volpe, Claudia Principe, Marcello Schiattarella: Unità stratigrafiche a limiti inconformi e storia evolutiva del volcano medio-pleistocenico di Monte Vulture (Appennino meridionale, Italia) “Unconformity-bounded stratigraphic units and evolutionary history of the middle Pleistocene Monte Vulture volcano, southern Apennines, Italy.”) Bollettino della Società Geologica Italiana., 125 (2006), pages 67-92.

Recommended reading for a short-length but solid summary of Taurasi and its neighboring appellations is the online article, Irpinia: The Heart of Campania, written in 2017 by Daniel Bjugstad, from the GuildSomm website. For an extremely comprehensive examination of the subject by way of subzones of quality Aglianico production (and published literally days after my initial draft of this essay in August 2019) is Ian D’Agata’s book, Italy’s Native Wine Grape Terroirs. Bravo Ian!

Monte Vulture Geology link: https://www.alexstrekeisen.it/english/provincie/vulture.php

Mount Saint Helens link: https://www.google.com/maps/place/Mt+St+Helens/@46.4611713,-122.1227831,9494a,35y,181.53h,67.79t/data=!3m1!1e3!4m5!3m4!1s0x54969956568a2691:0x69ddb4f4b6cf94c7!8m2!3d46.1914006!4d-122.1955508!5m1!1e4

Pompeii Video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dY_3ggKg0Bc

1944 Vesuvius Eruption: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1bsmv6PyKs0

DOC AND DOCG LAW link: https://italianwine.guide/about-italian-wine/wine-law/

Credit: www.climate-data.org provided the precipitation and temperature information.