Arribas Wine Company

This website contains no AI-generated text or images.

All writing and photography are original works by Ted Vance.

Short Summary

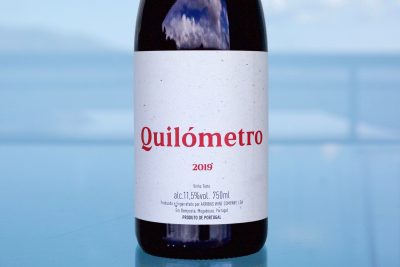

After years of research, friends and former Dirk Niepoort disciples and enologists, Riccardo Alves and Frederico Machado, began their own courageous project in 2018. In the desolate high altitude (600-700m) hills overlooking the Douro River (Duero in Spanish) of Portugal’s Trás-os-Montes, the territory is rugged, rocky, and steep; a terrain of ancient acidic Pangean-era rocks (mostly granite, schist and gneiss), variations of sand and clay, and far more than fifty indigenous varieties from ancient vines grown in an extreme continental climate with hot summer days and cold nights. Each of their red and white wines blend dozens of varieties and express their terroir with clarity. All the vineyard work is organic and done by hand with target alcohols between 10.5-12.5%. The wines are spontaneously fermented, and the reds usually have 100% whole bunches and are aged in old French oak barrels, concrete and steel. None of the wines are fined or filtered.Full Length Story

In the early summer of 2017, after harvests in the southern hemisphere, Ricardo Alves and Frederico Machado visited Bemposta for the first time together. They were on the Portuguese back roads in the Parque Natural das Arribas do Douro, with its wealth of ancient, indigenous and largely forgotten grapevines chaotically perched on the extreme slopes on the Douro river gorge, when they came upon the perfect location for their life project, the place to which they would commit their youth. They set out to rediscover and revitalize an ancient wine culture whose local home winegrowers have just barely kept the faint bloodline of their vinous history from extinction.

Meeting of Might and Mind

Frederico Machado (pictured above on the right), a native of Braga, one of Portugal’s larger northern cities, was born in 1986. He began his university studies at the Universidade do Minho where he studied Applied Biology from 2004 to 2006. Sidetracked by an interest in Medicine, he spent some years at the Czech Republic’s Charles University, in Plzen (or Pilsen; yes, the birthplace of the pilsner-style beer). In 2010, he was drawn back to finish his Applied Biology degree, which preceded a yearlong stint in Athens, Greece, researching protein models. But the call of the wild and his curiosity in wine began to consume his interests and he returned to Portugal to finish a Master of Enology degree by 2013 at the Universidade de Trás-os-Montes e Alto Douro (UTAD), in Vila Real.

Fred did his first harvest in the Douro with Dirk Niepoort in 2014; 2015/2016 with Susana Esteban, in Alentejo; Wine by Joe, in Oregon, 2016; Mitchelton (2017) and Tahbilk (2019), both in Victoria, Australia. He worked the 2019 harvest with Tahbilk to earn more money to support Arribas Wine Company, while Ricardo maintained the spring work back in Portugal.

Born in 1992 and raised in Bragança, a small city in northern Portugal, Ricardo Alves (pictured above on the left) attended UTAD from 2010 to 2013 where he earned a degree in Agronomy with a focus on viticulture and winemaking. He continued his pursuit of a Master’s Degree in Enology to further his understanding on the technical sides of winemaking. Through the years of study, he worked harvests at different wineries in Portugal’s Douro wine region (Quinta do Couquinho, Ramos Pinto, Quinta do Crasto, and the internationally famous Niepoort winery) and in the south in the Península de Setúbal at Pegos Claros. In 2016, he worked a triple harvest between Weingut Lothar Kettern and FIO Wines, in Piesport, Germany, and prior to that in the same year, he worked a harvest with the well-known “natural wine” Burgundian domaine of Philippe Pacalet, in Beaune. Ricardo explained that his work with Pacalet had the deepest influence on his perspectives and helped to set the course for his interests in wine philosophy.

The Birth of Arribas Wine Company

Both men made harvest in the southern hemisphere in 2017, with Frederic in Victoria, Australia, at Mitchelton Winery, and Ricardo in South Africa, at Saronsberg Cellar, in Tulbagh. Upon returning, they continued the discussion they started in 2016, a plan to embark on a project together that would reflect their ideas on wine. Fred explained, “My grandparents were born in Bemposta and Ricardo is from the Trás-os-Montes. After my father showed us some pictures of the old vineyards of Bemposta, with many of them abandoned, we made a visit. It was the first time I’d been back since I was a kid. We were amazed by the amount of old vineyards and the magnificent landscape. Even though it was June and the days were very hot, the nights were also surprisingly cold. This was how our quest for a spot with unique characteristics and diversity began. I’d been to Bemposta many times as a child, but the idea of returning never crossed my mind until that moment.”

Starting from Scratch

Arribas Wine Company’s main winery (as of 2021) is a rustic, low-ceilinged rock and concrete building partially underground, completely jam-packed with barrels, bottles and fermentation vessels, like a can of sardines—a fitting analogy within Portugal, a country famous for conservas. Bemposta is in the middle of nowhere and feels almost post-apocalyptic. Outside of town the houses look like quickly erected structures for a nuclear test site, and many buildings in the historic village center seem to have been abandoned for many decades, possibly even since the end of the last World War. Upon arrival, if it weren’t for the large black and white sign displaying the name on their garage-sized cellar in the center of town, one might think their GPS has led them astray. In 2020 they found a new storage space to expand production, in part because of domestic demand along with their surprisingly successful export business to Japan, Scandinavia and now with us in the US.

Frederico and Ricardo are at the beginning of their lifelong path to rediscover and play their part in the redefinition of this unique area of the Trás-os-Montes. When tasting unfinished wines with the duo they are able to explain what they’ve done with each of them, but are frank about how early in the process they are in understanding the vineyard material. They are starting almost completely from scratch, and there are few locals, if any, who have much to contribute regarding quality winemaking also with a broad palate and experience with international wines.

The reality is that the vinous history and wisdom in this corner of Portugal is buried in local cemeteries with remnants of it preserved within the DNA of the few remaining ancient vineyards. What shreds of useful historical viticultural information that may remain was passed down from one generation of home winemakers to the next, not through commercial wineries.

Missed Opportunities

The Trás-os-Montes has extraordinary potential. Wine professionals with even a basic sense of viticultural knowledge would quickly recognize how ideal it is for certain types of high quality continental climate grape growing. From a landscape perspective, it’s perfect for high quality grape growing: rolling hills, steep hills, infertile soils, interesting geological formations, warm to hot summer days with frigid nights, and precipitation at the right times. However, progress here moves at a glacial pace.

The stifling of the region can be attributed to many factors, but perhaps the greatest of them is, and always has been, its difficult location. If there were ever a classification of off-the-grid Portuguese wine regions within the country’s continental boundaries (it has many islands, like Madeira and the Azores), Trás-os-Montes would be in the running for the number one position. It’s located in the far northeastern corner of the country and is landlocked by mountains in the north, west and south, and high plains/desert to the east. When looking at a map, it looks like it’s not so far out there but it seems to take forever to get anywhere because of the windy country roads. It’s true that at least this arid and colorful countryside is one of the most beautiful in the Portugal, but the curves are many, so getting too caught up in the beauty around every corner while behind the wheel is not advisable.

Ricardo explained that records from the 1880s show just how extraordinarily expensive it was to transport wine and wine spirit for Port wine production in the Douro from Arribas (the far eastern end of the appellation) to other regions. In fact, most of the wine had to be hauled to the nearest railway station before being transported on to its final destination. Just from where they are today, in Bemposta, it was a thirty-six kilometers (around twenty-two miles) wagon haul without proper roads. Big barrels and containers of wine are burdensome and difficult to transport, and it was paramount to choose the right kind of weather to transport such things. The region produced high-volume wine for early consumption, likely fuel for the drudgery of agricultural work and a nightly escape from hard country living. It was cheap, and once that reputation is established, it’s hard to shake it—an all too familiar storyline in many great wine regions, most notably (at least in my mind) Chianti Classico, one of the world’s most undervalued wines with entry-level wines selling in stores for around $25 (as of 2021) even from the top producers in the region.

Talking Trás

Aside from the location, there are other elements that have played supporting roles in the suppression of this region’s high quality viticultural potential. Leading the way is the temptation to follow in the footsteps of the Douro’s success. This prompted many grape growers to replace local grape varieties with those that have been successful in the Douro, just to the south and southwest: grapes like Tinta Cão, Tinta Francesa, Tinta Roriz (Tempranillo), Touriga Franca, and Touriga Nacional. There are also French varieties that have found their way here, most famously, Merlot and Cabernet Sauvignon. This focus on what works (but from elsewhere) has not been helpful with regard to Trás-os-Montes’ identity crisis. The truth is that there is no greater time in the last half century to produce and globally market indigenous grape varieties or field blends no matter how quirky or off the rails they may seem to stalwart local (modern) traditionalists. If the Trás-os-Montes doesn’t regroup and focus on its local, historical grapes, they could again miss the boat. And with the comparisons to the Douro and wines in that style, the Trás-os-Montes will always be the bridesmaid and never the bride.

Everyone even slightly familiar with Portuguese wines probably knows Port, Vinho Verde, and a single rosé wine marketed in a sort of cognac or spirit bottle shape; I don’t want to name names, so let’s just call it M. M is produced by a big company we’ll call S. S started in the mid-1900s and at the time supplied a much-needed vision to bring Portuguese wines to the global market, which they achieved with smashing success. S was the answer in tough times, but today its thumb still presses hard on some wine regions, like the Trás-os-Montes. The contention of Arribas Wine Company is not only that S has monopolistic tendencies (and tactics), but the success of the business they created on the backs of the small grape growers in rural areas like the Trás-os-Montes has not been reinvested in the region. And they believe that it’s their business model that is largely responsible for creating a grape market in the Trás-os-Montes that excluded local grape varieties in favor of those from the Douro. Bulk wine companies like S economically incentivize growers to abandon their local vinous history and perpetuate the cycle of selling off their heritage just to get their ends met. And who can blame them? The Trás-os-Montes is not at all a wealthy area, and there is no savior on a horse to incentivize them to do otherwise. Or is there?…

The story of the Comissão Vitivinícola Regional De Trás-os-Monte (CVRTM), the governing body for the Trás-os-Montes appellation, is not an unfamiliar one in this part of the wine world—particularly of note, Spain’s Ribeira Sacra, where most of the great producers have abandoned the use of the D.O. regulations in favor of flexibility and a return to historical grape varieties over Mencía, a grape historically originating from further west in Bierzo and beyond. Northwest Iberian wine commissions (and many other wine regions) are hesitant to embrace wines made outside of the style in which they expect wines from their region should taste like—not a good idea for a sheltered and globally inexperienced region. The reality is that it is in more recent times that the laws of production were written. History is often overlooked, consciously or unconsciously, in favor of whatever seems to drive economics. The problem today is that this mentality limits the discovery and rediscovery of different wine styles. And in today’s global wine climate, the appellations are better advised to completely open up the discussion to allow these freedoms of stylistic choice. People (wine consumers) are no longer interested in being told by historic wine establishments what they should like, and neither are winegrowers.

At first, the idea of having a wine commission seems like a good one, but they are now largely a detriment to positive progress in areas with a big cultural wine gap through time. Often overly conservative, their perspectives (much influenced by their most established and successful winegrowers) may restrict not only the forward movement into the modern wine market, but also the reintroduction of the way wines were made in the past, long before the onset of regulation. Commission tasting panel judges who decide whether or not a wine is representative of a region may think that they are protecting it, but in some cases, they are likely holding it back.

The list of beefs Arribas Wine Company has with CVRTM is understandable: 1) they don’t allow the co-fermentation of different colored grape varieties (something both Arribas Wine Company and another winegrower we work with, Menina d’uva, do in most of their wines); 2) wines must be a minimum of 11.5% alcohol, which automatically excludes most of the wines produced by Arribas; 3) certain levels of clarity (turbidity) and reduction (or lack thereof) must be maintained with the wines—more strikes against Arribas Wine Company; 4) As of January 2021, the CVRTM doesn’t have its own wine testing lab, or tasting panel from the Trás-os-Montes, but rather they rely on the Instituto dos Vinhos do Douro e Porto (IVDP) as their tasting panel. Would growers in Italy’s Alto Piemonte let a commission from the Langhe decide the passable parameters for each appellation’s status? Then there is the complaint about the appellation’s subzones division and how Arribas is completely different from the other three. This will be outlined further along in the Lay of the Land section.

Arribas Wine Company Filosofia: Minimalismo

Not only do Frederico and Ricardo claim minimalism in the outline of their philosophical ideals, but in the early stages of their development and adaptation to their terroirs, they find it is essential to limit control of variables and “helicopter winemaking” to see with greater clarity what each vineyard renders in its most naked and unimpeded way. They want the wines to do their thing and discover a way to work with them to extract the best of what they have to offer, rather than conforming to the status quo, to what the market expects them to be. This can make tasting unfinished wines in their cellar—in order to get a sense of their progress—difficult to process. (And I can only imagine the thoughts of panelists from the commission of CVRTM or IVDP when they do the same…) Their unconventional approach therefore renders the incredibly good results of their finished wines a downright mystery or magic trick. It’s interesting—and very unusual as winegrowers—that Fred and Ricardo are not afraid to show visitors the full monty to simply demonstrate how trippy the wines can be at certain points in their evolution in the cellar. And if one feels befuddled by what one tastes (as I have on numerous occasions in their cellar), Fred and Ricardo are right there with you. The difference is that they’ve known these wines from the bud break up; they know the quality of their work and have full faith in it.

The combination of their gifted terroirs, technical education, practical experience, acquired skills and deep convictions reveal a glimpse of what can be possible. These two inspired, and inspiring, idealists are bound by nothing. They are free to meander, explore, test, think, fail. And triumph! Somehow they manage to bend and reshape their high-toned and vibrantly fresh wines from a state of raw distortion and abstraction in the cellar, to tensile equilibrium and beguiling beauty in the bottle.

You already have an idea about Arribas Wine Company philosophy: low alcohol (10.5%-12.5%), unfined and unfiltered (which influences turbidity), reductive with higher CO2 content during cellar aging with some CO2 left for bottling to keep the need for SO2 at a minimum. But there’s a lot more than these catch-all concepts that land Arribas Wine Company squarely in the natural wine movement.

To achieve their ideals they follow in the footsteps of tradition with simple and straightforward vineyard and cellar techniques, while using their scientific knowhow and a multitude of different experiences to bring the wines to form after the wild adventures just prior to bottling. Their traditional methods—similar to those employed centuries ago—include all work done by hand with no chemical or mechanized farming; no synthetic treatments except the use of sulfur and copper, obligatory vineyard treatments in all of Europe to combat powdery and downey mildew—if growing vines to produce grapes is the intent, whether under even organic, biodynamic and “natural” winegrowing culture; whole-bunch fermentations trodden by foot and punched down by hand to achieve gentle extractions; no pre-élevage filtration or extensive settling before putting the wines in barrels; gross lees contact throughout cellar aging to encourage stability and less dependence on sulfur additions (but, of course, at the risk of increased unwanted hydrogen sulfide/reduction issues); and no finings or filtrations before bottling by hand.

Frederico and Ricardo do as little forced manipulation to achieve the maximum natural expression of each terroir within the calibration of their palate preferences: high amplitude, fresh acidity, low alcohol, and adventurous but hygienic. Their goals for the future are to work with their own organic composts, seed-cover crops, and to reintroduce and encourage the recovery of indigenous micro and macro flora and fauna. Sadly, they did not walk into completely respectfully farmed environments when they first started to lease and work these old vineyards. Many were chemically farmed and cropped to sell to bulk wine manufacturers. There was and still remains a lot of work to be done just to get their vineyards up to their expectations.

The common table wines of the Trás-os-Montes are well known for tasting more like a fuel-based commodity made for the purpose of keeping the field workers going rather than to be shipped off to international wine markets. But before you click away based on this description, there’s hope! Hope in the form of wines from our rebels with a cause, Frederico Machado and Ricardo Alves (along with a heroine of the same movement in the Trás-os-Montes, Aline Domingues, with her winery, Menina d’uva), who manage to craft wickedly smart and progressive wines from ancient local grape vines in this nature-rich landscape.

Lost in Portugal? You are not alone…

If the Trás-os-Montes or, for that matter, any Portuguese wines are new to you, you are in the same boat as most wine professionals and consumers. Frankly, I consider myself ignorant on the subject given that the vast majority of my wine life has been focused on the wines of France, Italy, Germany, Austria, and just prior to Portugal, on Northwestern Spain. But what keeps it interesting to most of us is that there’s always something new around the subject of wine; it’s a choose-your-own-adventure that regularly reminds us of how little we know about the subject no matter how long we study it.

Trás-os-Montes is the obscure within the already globally obscure world of Portuguese wines. There’s even a wine from here aptly named, The Lost Corner. This is a consequence of many historical factors, including vine diseases, phylloxera, alien mildews from the new world, wars, poverty, and a dictatorship; you know, the typical European wine region challenges. Also, the commercial wines in Trás-os-Montes perhaps are, and may have always been, too rustic for the American wine consumer weaned on fruit-forward domestic wines and other more enologically polished wines from famous European regions, as well as various new world wines with more common grape names and familiar euro-phonetics found inside American culture.

After moving to Portugal in 2019 I quickly came to realize that American’s nearly non-existent references to Portuguese and Brazilian culture and language is perhaps the greatest culprit for the relative lack of presence of Portuguese wine in the United States. While every other major wine-producing country in Western Europe contributed a lot of immigrants to North America that brought their cultures along with them—particularly France, Italy and Spain—whose Romance languages and cultures are ubiquitous throughout the county, Portuguese wine fame is mostly limited to Port wine and to a lesser degree, innocuous bargain white, rosé and red still wines. High quality Portuguese wine has an uphill battle, whereas more value-driven wines are already on the rise in the US.

Trás-os-Montes Climate

Trás-os-Montes is a perfect agricultural stronghold for Portugal. Its grassy, shrubby moorland landscape quickly changes from spring green to early summer gold, and the landscape is littered with pine, oak, chestnut, citrus, and olive trees, animals, arable land crops, and, of course, a lot of vineyards.

Its arid climate is dramatically affected by the topography of the neighboring Portuguese appellation, Vinho Verde. Between the Atlantic and the Trás-os-Montes (which literally translates to “behind the mountains”), and throughout the Vinho Verde wine region, is a series of low-lying mountains that act as a rain shadow that gently squeezes Atlantic clouds before they pass through. These mountains, with the tallest at around one thousand five hundred meters (just short of five thousand feet) while most others sit much lower, cut the precipitation to around two-thirds or less of the average of the Vinho Verde.

While it rains a lot, with an average of more than seven hundred millimeters annually in the Trás-os-Montes as a whole, most of it happens during around nine days per month between October and May. However, it rains on average less than six hundred millimeters around Bemposta, the location of Arribas Wine Company’s vineyards. Yet the area manages to be quite arid in the late spring and summer when there’s an average of only two to four days of rain per month.

There’s also a large topographical variation between more mountainous zones, riverbanks and the plateau. In this region they are mostly quite exposed to the elements, especially on the plateau, and in the warmer months there is little, if any, influence from the Atlantic. This allows for fewer vineyard treatments than in other wine regions with summer rains that result in higher humidity and therefore more mildew pressure. The long, warm and arid summer days are the reason why the wines in the area are notoriously weighty and higher in alcohol compared to those from neighboring Vinho Verde, and are more closely calibrated to Spain’s Duero wine regions toward the east. However, the cool nights that sometimes drop more than twenty degrees bring the possibility of freshness to the wines.

Francisco Ataíde Pavão, the president of the Trás-os-Montes wine board, and a grower of olive oil, explained that there is a large separation of harvest times between the three subzones. Valpaços, which he described as having two seasons, “nine months of winter and three months of hell,” is the first to be picked. More or less two weeks later, Chaves is ready and after another two weeks, Planalto Mirandês.

Trás-os-Montes Subzones

The Trás-os-Montes is located in the far northeastern area of Portugal and is bordered by Spain to the east and north, to the south by Portugal’s Douro Valley and its tributary valleys, and to the south and west by the Vinho Verde. Aside from the overarching classification of the wines as the Vinho Regional, Transmontano, it’s subdivided into three main DOC subzones, and spans from the center of Portugal’s northern border to the easternmost area of the country.

Chaves is the smallest of the three DOCs and is located in the most northwesternmost section of Trás-os-Montes, just across the border from Galicia’s Monterrei wine region, home to the famous and talented Galician revisionist, Jose Luis Matteo, who makes extraordinary wines bottled under his Quinta da Muradella label. In the middle is Valpaços, with a lot of soft hills and waterways, and the DOC subzone furthest to the east and on the border of Spain, is Planalto Mirandês, which sits on a plateau known as Serra do Mogadouro.

Arribas Wine Company’s vineyards are located in the easternmost subzone, Planalto Mirandês. This area borders the famous Douro River (known in Spain as the Duero) on the east/southeast side, just across from the new (since 2007) Spanish wine region, Arribes, named after the national park, Arribes del Duero, or Arribas do Douro, in Portuguese. The general landscape of their territory is mostly rolling hills and small valleys created by waterways, until you arrive at the Douro River. Here, the vineyards above the river gorge are on flatter areas, and others inside the gorge on extremely steep hillsides. A more extensive overview of Arribas is further below in the section, Arribas, Arribas, Andale!

Trás-os-Montes Geology

Geologically, the Trás-os-Montes is part of the Iberian Massif, a remnant of Pangaea, Earth’s last supercontinent that was comprised of all the current continents, a few hundred million years ago. It’s geologically similar to France’s Massif Central (Northern Rhône, Beaujolais and many more) and Massif Armoricain (western Loire Valley), and many other European wine regions. Like those areas, it is largely composed of igneous and metamorphic bedrock. There are also a lot sedimentary alluvial depositions, especially in Chaves, which are most often found in and around the small tributaries and the main river, Tâmega, known for its hot springs (so naturally the Romans left traces in the area), which starts in Galicia and travels south, eventually spilling into the Douro.

Within the Chaves subzone, vineyards up and outside of the river’s influence are mostly composed of intrusive igneous granites or granodiorites (a rock that looks like what we commonly call granite, but differs slightly in its mineral makeup), and a smaller proportion of metamorphic rocks, perhaps predominantly graphite schist. Because the Chaves DOC ends at the northern border where Spain’s Monterrei DO begins, the bedrock can be similar in Monterrei from an overall geological perspective, but there is an increase of metamorphic rocks found here in addition to the intrusive igneous rocks. Chaves is at a lower altitude on average and is warmer compared to Monterrei. The lowest altitude vineyards sit at around two hundred and fifty meters and extend up to about four hundred. Monterrei’s vineyards can rise to hundreds of meters beyond that.

The neighboring subzone to the west, Valpaços (a compound spelling of Vale de Paços), has a large variation of vineyard settings with a mixture of some on very flat areas and others on softer sloping hillsides with a high desert-like landscape. The range of vineyard altitude is between two hundred and five hundred and fifty meters. The area as a whole has a broad geological diversity typical of the area with most of the bedrock either igneous or metamorphic, the latter predominately quartzite and graphite schist. Like the majority of Trás-os-Montes, Valpaços most commonly produces sturdy, rustic wines, while a few others take a stab at international varieties with a more polished finish.

Planalto Mirandês is where the geological fun ratchets up a few notches for us, not only because we represent two neighboring winegrowing teams there (Arribas Wine Company and Menina d’uva), but also it seems to have a different energy and quite a different setting than the other two subzones. The vineyard altitude here ranges between four hundred and seven hundred meters, making it the highest in the region.

Once one sets foot in the Planalto Mirandês it becomes easier to understand why three young, globally-minded wine fanatics and naturalists in search of a place to set up shop might choose to go there. Nature abounds. It’s serene. It has a beautiful countryside with a big sky. There also seems to be endless possibilities with such fabulous dirt and weather for grapes, and a multitude of grapes to choose from. These ancient grape varieties have quietly survived through the years while different crops and more productive and/or international grape varieties replaced others.

From a geological perspective, depending on location, most vineyard bedrock and soil is igneous granite or granodiorite, and/or the all-star cast of metamorphic rocks: mostly schist, but also a lot of slate and gneiss. The real difference here is the location and the steep, southerly-exposed barren granite hillsides where Arribas Wine Company’s vines overlook the Douro. They are quite the opposite of Menina d’uva’s that sit on rolling hills and altogether different bedrock, topsoil and exposure. (For more geology talk and Trás-os-Montes in general, go here.)

Arribas, Arribas, Andale!!

After passing westward through Castilla y León’s expansive sedimentary basin (filled with calcareous depositions that impart magic to many of its historic wine regions) in northern Spain below the Cantabrian Mountains and above the System Central (which includes the Sierra de Gredos and Sierra de Guadarrama mountain ranges, just west and north of Madrid, respectively), the Duero River transitions into the ancient Pangaean remnant, the Iberian Massif. Here, it takes a hard left turn toward the south at the Portuguese border and assumes its Portuguese name, Douro, at least on the Portuguese side. It continues its run as a natural border between countries for a stretch of a hundred and twelve kilometers (seventy miles) and through the Spanish and Portuguese national parks, Arribes del Duero, in Spain, and Arribas do Douro, in Portugal. The cliffs that overlook the river here are known as arribas, or arribes.

Massive and extremely hard granite and gneiss outcrops with some rocks as old as six hundred million years caused the quick southward turn of the Douro. Carved out by the river in former times, it left a massive, irregular gash in the landscape with many expositions that made it ideal for viticulture. Much of the bedrock in the vineyard area of Arribas Wine Company is granitic and on steep vineyards facing the river gorge. The topsoil is largely derived from the bedrock, especially further uphill away from the river.

Arribas is quite different from the rest of Trás-os-Montes. It’s on steep hillsides and is subjected to many variables that make for very different wines from the rest of the appellation, and even quite different from the rest of the Planalto Mirandês. Not surprisingly, it has a much greater relation to the Spanish D.O. across from where the river is aptly named Arribes. With the majority of Planalto Mirandês on rolling hills with a varying degree of igneous rocks but also a lot of low-to-high-grade metamorphic rock formations, the combination of these geological and topographical elements is enough to reshape the mouthfeel of the wines, and influence the degree of ripeness and taste profile of the fruit.

Then there’s the soil grain, which in the flatter areas of the Planalto Mirandês range from clay, silt, sand, gravel, and cobbles, with much of it derived from somewhere other than the underlying bedrock. By contrast, Arribas Wine Company’s vineyards are extremely steep, but not quite as steep as Mosel Valley, or Ribeira Sacra subzone of Amandi. After thousands and thousands of years, anything but more recent erosion (and I use this term from a geological time-frame, so quite a long time depending on each site, decades or centuries) from the bedrock itself would’ve found its way down the hill and into the river, or close to it. Most of their numerous vineyard plots (15 plots, as of 2020) are on granitic bedrock and topsoil with clayey, loamy and/or sandy soils, with most, if not all, derived from the bedrock.

The altitudes range from five hundred to seven hundred meters (sixteen hundred to twenty-three hundred feet), quite a bit higher on average than most other winegrowing areas of Trás-os-Montes. These high altitudes naturally bring a much-needed strong diurnal shift for this arid and exposed landscape. The rainfall averages just short of six hundred millimeters each year (which is half of what falls in Portugal’s Vinho Verde, just over the mountains toward the west) and most of it comes in the winter and spring—optimal for mildew management.

Trás-os-Montes Grapes

In the 1980s when the cooperativas (co-ops) started their collapse (read more about that here), many grape growers replaced their vines with mostly olive trees, the primary agricultural output of this area. Others replanted vineyard land from the historically local grape varieties to those from further south in the Douro, as well as other international grapes. The move is an understandable one, especially given the highly adaptable blank canvas the Trás-os-Montes offers to the commercially dominant grape varieties, particularly for reds. With a global market dominated by the now ubiquitous French single varietal wines, any sensible businessperson in search of solutions for a market outside of the country’s impoverished domestic market would consider these international grapes as an option, especially after generations of rigid dictatorship that finally ended in 1974.

Interestingly, the climate and landscape of Trás-os-Montes is quite similar to much of California’s wine country, so it would make perfect sense to dream bigger and follow the footsteps of even that state’s very successful modern wine industry. But one major difference is that early on, California’s consumer populations could almost single-handedly support most of its wine production and all of the extraordinarily high costs that come with it. The people of Portugal have never been able to follow suit, nor has the country really been able to compete on the world stage to support such a progression even within its most promising wine regions. And so the move toward international varieties was short-lived and in recent decades most new vine plantings have been made with indigenous Portuguese grapes historically from outside Trás-os-Montes, with many destined for the bulk wine market. Interestingly, white wine production has been on the increase and has steadily grown from 10% of the region’s output some decades ago to now close to 30%. A lot of these new white grape plantations are at a higher altitude and on hillsides rather than flatter areas.

So what about the local Portuguese grapes with the greatest marketing potential? Well, their first hurdle is that they’re a mouthful to simply pronounce correctly. Add to that the fact that most of them are a mystery to even Portuguese wine specialists and winemakers. Indeed, those within specific regions know their own grapes, but because there is so much blending in all the regions, it’s difficult to know the specific nature of even a specific grape grown in one region compared to the same grape from another. There are literally hundreds of these indigenous grapes that are unknown to all but a few people outside of Portugal, and many of them have more than a dozen different names.

Common Trás-os-Montes Grapes

(you’re on your own with the pronunciation)

Whites (Branco): Viosinho, Arinto, Rabo de Ovelha, Donzelinho Branco, Gouveio (Verdelho), Códega do Larinho, Malvasia Fina, Fernão Pires, Malvasia Fina, Rabigato, and Síria. Reds (Tintos): Touriga Nacional, Touriga Franca, Tinta Francesa, Tinta Cão, Bastardo (Merenzao in Spain; Trousseau in France), Tinta Amarela (Trincadeira), Tinta Barroca, Marufo, and Tinta Roriz (Tempranillo).

Arribas Wine Company Grapes

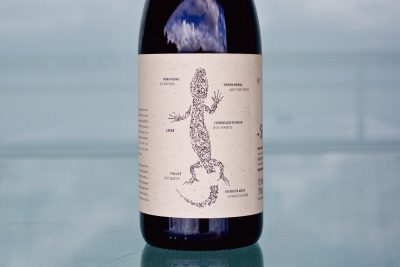

The following grape list and notes come directly from Frederico and Ricardo. Incredibly, they work with each one of the listed grapes and there isn’t a predominant grape variety in their cellar.

White Grapes: Malvasia; Verdelho Branco; Bastardo Branco; Posto Branco; Donzelinho Branco; Códega, a different grape from the Douro variety called Códega do Larinho; Rabigato, also commonly known as Puesta en Cruz in Spain’s Arribes; Palomino, also present in Spain’s Arribes and can be identified by the red leaf stalks; Formosa, a table grape that produces big bunches with big grapes and is sweet and juicy.

Red and Pink Grapes: Tinta Gorda, also known as Gorda in Portugal and Juan García in Spain; Bastardo, also known as Bastardillo Chico in Spain’s Arribes, and Trousseau in France; Rufete; Tinta Amarela, also known as Negreda and one of the varieties that has originated in Trás-os-Montes; Alfrocheiro, also known as Bruñal in Spain’s Arribes; Alvarelhão Brancelho, also known as Albarello or Brancellao in Spain; Mourisco, also known as Marufo; Bastardinho and/or Bastardinha; Tinta Serrana, a variety that crops very close to the trunk, often with small berries and somewhat long bunches that are difficult to harvest due to all the leaves; Alicante Bouschet, or another related variety with red-colored flesh, that we have found in some vineyards; Verdelho/Vermelho, also know as Verdejo Colorado in Spain’s Arribes—a fascinating pinkish, light-purple-skinned variety called Verdelho or Vermelhoa, which is a clone of the white grape, Verdelho, and identical in terms of behavior and cropping/foliage/growth; Uva-de-Rei, a table grape, used for drying and raisins for Christmas, produces long, airy bunches with big pink grapes that are very acidic and fleshy; Dedos de Ama; Moscatel, of which Arribas Wine Company has at least a few plants in each vineyard parcel and is described by them as a “fantastic copper/bronze/light purple-colored grape.”

Each of the Arribas Wine Company’s wines that we import has the details covered on their product pages.