About The Wine

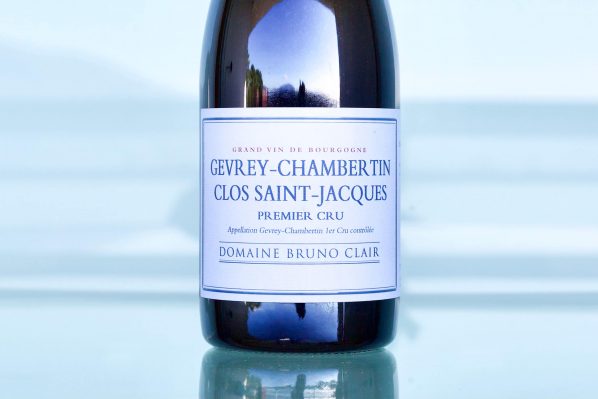

On the hill of Saint-Jacques we find two of Clair’s most important wines, two premier crus of the highest quality: Les Cazetiers & Le Clos Saint-Jacques. This hill, removed from the grand cru hill which begins just a bit south and across the Combe Lavaux, through the village of Gevrey-Chambertin and slightly to the east, is inside the Combe Lavaux—one of those former waterways that while now dry, is a funnel for cooler winds from the cooler forest areas further toward the west. While this brings advantages against hot weather, it can also bring in hail and cold weather at times when heat is needed. It appears that as the climate continues to warm up, the wines from this hill will begin to find more opulence than they have had in the past; a familiar story of our modern age.

Another interesting consideration is that the vineyards of the hill are on the average slightly higher than those of the Chambertin hill, home to all the grand crus of the commune. For example, Le Clos Saint-Jacques begins more or less around 280 meters and goes up to 340 or 350, while the grand crus with the highest elevation top out slightly above 300. Altitude affects ripeness and alcohol balance with full fruit maturity, since the higher you go the cooler it gets.

Clair’s Les Cazetiers (which he labels without the Les) is high up on the slope somewhere between 310 and 350 meters, whereas his Le Clos Saint-Jacques (also missing Le on his bottle label), like the parcels of the other four growers of the commune, goes from the top to the bottom. His Le Clos Saint-Jacques vines were planted in 1957 and 1972, while Les Cazetiers was planted in ‘58, ‘72 and ‘96, and sit closer to the northern end of the vineyard.

The depth of topsoil from the bottom of the hill to the top varies, and of course the further up you go, the thinner it becomes. So, you can imagine that Les Cazetiers from Clair’s parcel is on whiter clay with very little, if any red or brown tones. Le Clos Saint-Jacques is white on top, and at the bottom a more brownish and deeper clay topsoil. The separate parcels from the five different owners of Le Clos Saint-Jacques, like Gevrey-Chambertin’s grand cru, Clos de Bèze, are divided up so that the vine rows start at the bottom and go all the way to the top—making for more potential layers of complexity in the wine, but also perhaps less specific dominant characteristics.

Les Cazetiers is often overlooked because of its illustrious neighbor, Le Clos Saint-Jacques, who many consider to be one of the Côte de Nuits’ top super second premier crus, alongside of Les Amoureuses in Chambolle-Musigny and Aux Combottes in Gevrey-Chambertin, for example. Les Cazetiers is no pushover—and most who can see past Le Clos Saint-Jacques throw it into the “super seconds” of the Côte’s premier crus, myself included—and Clair’s version is almost always more expressive immediately out of the gate compared to Le Clos Saint-Jacques.

Le Clos Saint-Jacques is one of the slower burns in all of Burgundy’s great wines. It’s better served to fewer people, while Les Cazetiers often performs in shorter order, at least from Clair. I get suckered into the allure of Clair’s Clos Saint-Jacques, but many vintages of his Cazetiers have a longer drinking window in their youth and don’t need a lot of time to get going. Interestingly, Les Cazetiers is more often than not Bruno’s preferred of the two from the hill.

We could sing praises to Le Clos Saint-Jacques all day. With three of its five owners being some of the most compelling names in the business: Armand Rousseau, Jean-Marie Fourrier and Clair; the other two owners are Domaine Louis Jadot and Sylvie Esmonin—both can make fine examples of the wine as well. Le Clos Saint-Jacques is a king of a premier cru. Its demeanor is one of contemplation before action. It’s slightly more southeast facing than Les Cazetiers, which is an advantage needed to ripen it fully in cooler years—if they should exist anymore. That length from top to bottom is enviable for any great cru. Think about La Tâche, in Vosne Romanée, for example, compared to Romanée-Conti and La Romanée. The latter two are smaller and perhaps more particular, but imagine what kind of wine you’d have if you blended them together with a sizeable chunk of the best part of Romanée-Saint-Vivant below them. You’d get layered complexity like La Tâche does, and the same can be said of wines rendered from Le Clos Saint-Jacques. It’s got serious range and if one doesn’t have the patience to wait for it, one should go the direction of Clair’s Cazetiers, or Petite Chapelle.[cm_tooltip_parse] -TV [/cm_tooltip_parse]

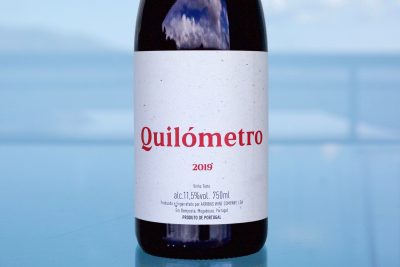

Mateus Nicolau de Almeida

Mateus Nicolau de Almeida