Enrico Togni-Rebaioli

This website contains no AI-generated text or images.

All writing and photography are original works by Ted Vance.

Short Summary

Inspired by his grandfather’s vinous hobby, Enrico Togni-Rebaioli left law school to work as a farmer. His organic (certified) and biodynamic 3.2 hectares of vineyards are co-planted with intermixed gardens and countless fruit trees surrounded by wild, verdant alpine brush and forest below limestone bluffs. These limestone terraces rich in organic material are lightly covered with calcareous sand and sit between 250-400 meters of altitude. His labels are an ode to the Valcamonica petroglyphs and are without DOC classification, and he focuses on Nebbiolo and Erbanno, the latter a Lambrusco family variety. His still red wines are naturally fermented with full stem inclusion and principally age in old concrete vats (with the Nebbiolo 1703 on skins and stems for six months!). Sulfites are used sparingly (when used at all) with his metodo classico sparkling wines aged for 18 months on their lees with no added sulfites or dosage.Full Length Story

A true original and dedicated naturalist, Enrico Togni stands out in northern Italy’s nearly forgotten wine regions of the Valcamonica. An ancient valley made from rock created hundreds of millions of years ago uplifted by the alpine orogeny and recently carved out by glacial movement, the Camonica Valley’s vinous history during Enrico’s grandfather’s generation was about survival, not the freedom to experiment in pursuit of making better wine. Enrico explained, “The post-World War generations were so poor that if their wines went the wrong direction, they didn’t eat. I produce to enjoy. That’s the difference. When they produced something, it had to yield financial results. They had no room for error, but I do.”

First Impressions

My first contact with Enrico’s wines ended up a head-scratching curiosity because of their uniqueness, followed by a long contemplation of how he created such quirky wines with so many compelling and addictive qualities. The first samples tasted were very recently bottled and were, at the start, slightly unsettled and gassy—the latter element I correctly assumed was because he preserves the natural, dissolved carbon dioxide left over from fermentation processes to preserve the wines through their cellar aging, which only needs more bottle time to calm down. Enrico said that, “The problem with truly natural wines is that they are not stabilized or filtered, so there is sometimes some CO2 gas; my only tools in the cellar are time and the vessels for fermentation and aging.”

Each of these young wines had a very good first day, but during their second they opened and flourished in ways I hadn’t anticipated, nor had I experienced wines quite like these before. The lightly extracted version of the red grape, Erbanno, and his Nebbiolo (a foreign grape variety in these parts, although not so far from the Valtellina, in the neighboring glacial valley to the northwest) blossomed with exquisite alpine freshness and beautifully untamed but clean and rarely found naturally precise fluttering nuances. I’d never tasted, or even heard of Erbanno (and neither had any sommeliers I worked with) and was smitten. The Nebbiolo, bottled under the 1703 label, was a thrillingly subtle whole cluster version (very unusual for Nebbiolo) of this most noble variety that tops my list of grapes responsible for some of the most emotional experiences of my red-wine life. The only thing that went wrong was that I failed to do my intended due diligence with the wines by tasting them over a three-day period to see if red flags might begin to pop up because my wife and I obliterated these irresistible bottles by the end of their second day.

Becoming Enrico

I am aware that to use “a true original” to describe someone is perhaps a bit cliché, but for some who carry its full meaning, it’s perfectly fitting. The view that Enrico is truly original doesn’t only prevail in the region where he produces wine—where among the local vignaioli (the Italian equivalent to vignerons) he believes that most people think he’s completely crazy— but it also spills over into the world outside of wine.

At lunch during our first meeting, Cinzia, his partner and the mother of their daughter, Martina (born in 2010 and one of his most trusted quality-assurance palates), lovingly told many stories about Enrico and his unique obsession with farming, and about some of his vineyard workers who happen to be a flock of sheep. “First of all,” Enrico explained, “if you work all day in the vineyards, it becomes hard because the work is monotonous. I need something to stimulate my mind and planting and growing other things is important. Every morning I start my day by going to say hello to my sheep. I don’t spend too much time with them, maybe about ten minutes in the morning and at night. I take care of them, and I like it.” Cinzia chimed in, “And when he likes something, he goes completely crazy with it.”

The best of the potentially embarrassing stories recounted by Cinzia that seemed only partially embarrassing to Enrico was about how much he loves animals. She explained that unlike other children, on his sixth birthday he asked for and got a sheep, on his seventh birthday he got a donkey, at his eighth, a pony—and none of them were the stuffed versions.

With his appearance closer to an outback tribal Aussie cobber mixed with a Colorado mountain granola-type, Enrico isn’t your typical Italian vignaiolo. His bushy, chaotic curly locks, wildly intense eyes magnified by his glasses, and his mischievous looking but honest and earnest smile allude to his anarchic, commedia dell’arte personality. His speech flows ceaselessly with a steady stream of witty and light-hearted punchlines countered with hard-hitting, philosophical beliefs. Enrico is his own man, committed to the truths he’s discovered in nature, not only for his crops and animals, but also in the human condition and how it (he) needs to adapt to rejoin the natural order as the animals we are, in order to survive our modern existential dilemmas of the abuse to our planet and the resulting climate change that is now well underway.

Enrico’s Path

In 2003, inspired by his grandfather (also named Enrico, a man who worked in vineyards after World War II while making a living by producing electrical tools) Enrico quit his pursuit of a law degree—something his father had wanted him to do—in search of a more fulfilling life with a deep connection to nature. Prior to planting new vines, he undertook extensive viticultural studies (though not a formal education in wine and agricultural sciences) and followed the conceptual line of seeing the entire terroir and its surrounding and interior ecosystem as a single organism before deciding how he should approach his plot of land with balanced biodiversity in mind.

Valcamonica seems lost and so far behind compared to Italy’s numerous celebrated wines stories, except for the Franciacorta DOCG sparkling wine zone that sits at the mouth of the valley facing toward Italy’s expansive Po Valley. Its lack of clear direction beyond production as a commodity (outside of Franciacorta) perhaps gives Enrico the opportunity to choose grapes he finds to be most suitable for the unique limestone ground he will work. Most are local grapes, with a particular focus on Erbanno, an almost completely lost Lambrusco biotype he discovered in his grandfather’s vineyards, and others not at all local, most notably Nebbiolo.

Almost twenty years after redirecting his life focus, Enrico stands as a modern-day pioneer in his valley both philosophically, with his full commitment to organic (certified) and biodynamic practices, and his uninhibited cellar agenda to craft whatever inspires him. There has never been a better time for the acceptance of experimentation the world over, no matter what flaws may surface in a finished wine—though as mentioned, Enrico’s are quite clean on that front. Today’s “natural wine” movement, whose greatest contribution to wine may not be the wines themselves, but rather that it opened a gateway for discovery for guys like him, without too much in the way of market repercussions. (Though some have been saved from financial failure with get-out-of-jail-free cards for downright negligent work, thanks to the support of the industry’s most blind ideologues.) Enrico can fly freely and be creative in the ways he wants without losing his shirt in the process, as former generations would have.

The good news for those of us with high expectations for a wine’s craftsmanship is that while Enrico lives and works in an extremely natural way and couldn’t care less about outside expectations, his wines today are cleanly crafted and transmit his ideas with spectacular clarity and authenticity. We began our work together with his beautiful 2018 wines, and while there was a nearly non-existent 2019 vintage due to losses from hail, the 2020s out of barrel and tank are simply spectacular and vibrate with nervy energy balanced with an emotionally moving tenderness. Something special has already started at Togni-Rebaioli (the last names of both of his parents), and a lot more of the same seems imminent.

Lay of the Land

Outside of Northern Italy’s ancient Lombardian city, Brescia, heading north on the highway and into the mouth of Valcamonica leads you into its long, flat-bottomed glacial valley surrounded by mountain cliffs on both sides, and an almost immediate, unexpected, and magnificent view of Lago d’Iseo, home to the largest lake island in Italy and Southern Europe, Monte Isola. The rectangular, submarine-looking, Jurassic limestone island that quickly rises to more than four hundred meters above the surface of the water below is truly a stunning image. Sadly, driving through you’re only able to see its magnificence in bits and pieces as you slowly go downhill from one tunnel on the east side of the lake to the next.

An hour’s drive north from Brescia and fifteen minutes from the northern tip of Lago d’Iseo, further back into this ancient glacial valley with its last major scars carved out by Pian di Neve glacier about fifteen thousand years ago (Italy’s largest glacier that continues it regression further back into the Adamello mountains where the Adamello massif peaks at 3539 meters), we arrive at Boario Terme. This is the home and cantina of Enrico and his family (including the sheep), their farm of grapes, potatoes, cherries, apples, cereals, truffles, spelt, honey, and more. “In the mountain culture you cannot produce just one thing. It’s not correct. You need to produce a lot of different things, but not a lot of each different thing. I spend a lot of energy producing everything, not only wine.”

Winter Sun, Summer Rain?

It rains a lot in Valcamonica, and Enrico says that climate change here hasn’t been as extreme or noticeable as in other places. He explained that the weather is unexpected for outsiders because in the winter it’s very sunny and, by contrast, it rains a lot in summer. The average annual rainfall is about 900mm per year, while further back into the more mountainous sections of the valley, it can be as high as 2200mm per year, an immense amount of rain. What’s interesting and unexpected, is that in the Südtirol and Trentino area, in the glacial valley just to the east, rainfall varies greatly, from 1100mm in Bolzano (the capital of Südtirol and home to Fliederhof, a producer we also import) to less than 500mm in the Val Venosta (home to another of our winegrowers, Falkenstein) a thirty-minute drive northeast of Bolzano, almost directly north and less than 100km away from Enrico.

Valcamonica with white limestones on the left and red volcanic rock on the right

Rock and Ice

Glacial valleys are extremely common in northern Italy’s Alps and are a big part of many wine regions, like the Valle d’Aosta, Alto Piemonte, Lombardia (most notably, Valtellina), Veneto’s Lago di Garda wine regions, and Trentino/Alto Adige (Südtirol). Glaciers scratch deep into landmasses and mountains through thousands of years, creating unique u-shaped valleys with a flat bottom and steep cliffs on each side. In the process, they leave glacial debris at the base of each hillside (quite often more of a cliffside), presenting many opportunities on which to plant south-facing vineyards.

Unlike most of the glacial valleys in Italy’s Alps (especially those further west), Valcamonica has some quantity of limestone, but it is in the minority. These ancient sedimentary depositions of calcium carbonate-rich marine life were deposited 240 million years ago in the Triassic geological epoch (about 60 million years before the limestones of France’s Côte d’Or began to form similarly under a shallow body of warm sea water) shortly after Pangea began to break up. Valcamonica’s limestones were partially eroded during the ice age, and some accumulated loosely on the bottom of the south-facing (northern) hillside. These limestone depositions are home to Enrico’s vineyards and other crops as well as his small animal farm.

The Vineyards

“The most important person in the winery is the agronomist, not the winemaker. If the soils are healthy, the plants and grapes are healthy too.” – Enrico Togni

Enrico’s 3.2 hectares of vineyard sit on limestone terraces between 250-400 meters of altitude at the foot of limestone mountain cliffs within a small area of the south/southeast facing hill. The mountains that surround the valley range between 1400-1700m of altitude. In a discussion about Nebbiolo, Enrico pointed out, “The highest Langhe vineyards with Nebbiolo are around 500 meters but they are at the top of the hill. Here, we are at the base of mountains. It’s a totally different situation regarding exposure, wind, rain, and the influence of the altitude in a mountain terroir like this.” These differences are felt in the wines. Enrico’s Nebbiolo seems almost like an aromatic distillate of a complex Barolo where everything harsh and intense are removed and it’s left with lifted subtleties and a softer frame, and here you’ve arrived at Enrico’s mountain Nebbiolo.

Limestone is a unique feature in the valley on the north hill. The other side of the valley is composed of volcanic and sedimentary rock referred to as the Verrucano Lombardo, depositions that took place after the Variscan orogeny—an ancient mountain chain (referred to as the Variscan mountains) whose broken-down remnants are scattered throughout the world, including the US’s Appalachian Mountains, Spain and Portugal’s Iberian Massif, France’s Massif Centrale, Massif Armoricain and most of Corsica, and other parts of Italy (Sardinia, Calabria), Austria (Wachau, Kremstal, Kamptal), and Germany. Interestingly, in the center of the valley just across from Enrico’s vineyards, perhaps only a half kilometer away, is a unique and seemingly random and solitary, iron-rich, red volcanic site in the middle of the hill.

Everything in Enrico’s vineyards and farm are done by hand, or with machines that are hand operated. The topsoil is composed of around 60-65% calcareous sand (a perfect soil type for the amount of rain in this valley, and also a strong contributor to the elegance and lift of his Nebbiolo), very little clay and a lot—Enrico says perhaps an overload—of organic material. One of the unique problems Enrico has with his vineyards is that there is “too much vitality in the soil,” which sometimes hinders grape production. The naturally high nitrogen levels greatly favor vigor over yield which makes for potentially massive canopies and shorter root structures, resulting in fewer grapes. One of his solutions is to consider plowing, but he hesitates to disturb the micro flora and fauna above and below that has developed over the years of his gentle work since the planting of the vines.

The Wines and Grapes

“Nobody really cares about the appellation rules anymore, but people want to know what they are drinking.” -Enrico Togni

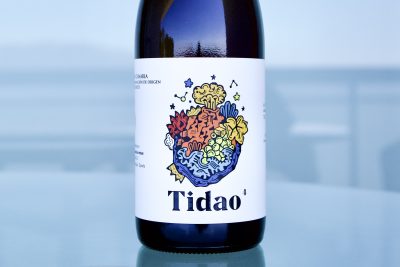

What appears to be cryptic label design markings on Enrico’s wines are an ode to the Valcamonica petroglyphs (prehistoric illustrations on rock through etchings, carvings, drawings, etc.) that, in 1979, became Italy’s first of many recognized locations by UNESCO as a world heritage site due to the more than 140,000 ancient wall illustrations that according to their website, “Depict themes connected with agriculture, navigation, war, and magic.” Some of the other cryptic elements on the labels, including no mention of grape types, appellations, or vintages are codified in lot number on the label, like LNEB18 (lot Nebbiolo 2018), with the last number correlating to the vintage, are due to his indifference to these categories, or their impossibility for certification because they don’t fit within local governing appellation rules. This same type of codification is commonly found in Spain’s Galicia and Northern Portugal.

All of Enrico’s still red wines are made with 100% whole clusters and are naturally fermented and aged in concrete or very old wooden casks. Sulfur additions are made only at the end of cellar aging prior to bottling and have a maximum SO2 level of 25mg/L (or 25ppm), of which 13-15mg/L are naturally present after fermentation. The sparkling wines have no added sulfites and zero dosage (qualifying it as a true “zero-zero” within the natural wine category). None of the wines are fined or filtered and have no additional additives aside from sulfites.

The grapes of his focus are Barbera, which he makes into a sparkling wine, a Nebbiolo still wine, and a few different wines from Erbanno, a member of the “Lambrusco” family that requires far less treatments (usually one for every three compared to the others) in the vineyards because its thick skins, which provide a naturally stronger immunity to mildew and disease.

Enrico first encountered Erbanno in his grandfather’s vineyard planted in 1960. He saw that Erbanno was different, and in 2008 he planted it and produced the first red in 2012, in a typical red wine style, labeled San Valentino. In 2015, he made his first lighter extracted version, labeled as Rosato “Martina,” and in 2016 the first sparkling rosato, Martì Cuntrare.

Erbanno is related to Lambrusco, and Italians speak about Lambrusco not as a grape, but rather as a family of grapes. Similar to the Caíños in northwest Iberia and the Malvasias in Italy and Portugal (which have been said to not be related), the Lambrusco biotypes present depend on the region, but they share the common characteristic of high acidity, like the Caíño clan from Iberia. Erbanno is known as Lambrusco Maestri, and often used to produce a darker red version of Lambrusco.

Both of his sparkling wines have zero dosage and zero added sulfur and are made in the metodo classico way. L’Attaccabrighe (“wrangler” in local dialect) is composed entirely of Barbera, a grape with extremely high acidity and almost non-existent tannins. And Martì Cuntrare (which is an Italian reference to a stubborn child who does the contrary to what is asked of them) is a sparkling rosé made entirely with Erbanno that is pressed immediately without any intended maceration. Both are aged for eighteen months on their lees before bottling.

There are two still versions of Erbanno. The first, labeled “Martina,” has almost no extraction and is pressed quite early. It’s normally labeled as a Rosato, though I asked that Rosato be removed from the label (at least for our market) because it behaves in almost every way much closer to an extremely light red due to its brighter performance at cooler red wine temperatures with a similar expression to that of a Premetta, a very light Schiava, Poulsard, or even the Galician variety, Brancellao, and it deserves a better fate than to be lumped into the Italian Rosato category. In 2018, the wine is lighter in color than 2020, but Enrico is happier with the direction of “Martina” with its slightly riper fruit in the 2020 vintage, which had grapes picked only one day before those used for the more classically styled red Erbanno. The 2020s are gorgeous wines across the entire range.

The other still wine from Erbanno, labeled as San Valentino, is darker and a more classically extracted red. During the earlier phases just after bottling it can be a little shut down because of the intended reductive approach Enrico employs during the cellar aging to keep each wine’s freshness and aromas as preserved as possible, and to allow for their single sulfur addition to wait until bottling and with a very judicious dose with a maximum of 15mg/L addition. As previously mentioned, it is a more gamey red but still retains the higher tones of Erbanno, making it a unique experience for anyone, as it indeed may be the only known wine of its kind.

His Nebbiolo, labeled 1703 Millesettecentotre Vino Rosso (named after the highest nearby mountain whose altitude is 1703 meters), should be sought out by all Nebbiolo junkies. It is very light in color and layered with extremely delicate Nebbiolo nuances, especially the variety’s classic sun-roasted red and orange rose aroma.

Enrico believes that his great challenge with Nebbiolo is simply that there are no references for it in his area because he’s the only one who grows it, outside of another who only produces 500-1000 liters per year. Regardless, he has a fantastic grip on this talented grape and the proof is in the glass. As already mentioned, it’s fermented with whole clusters fully intact (a very unusual choice for this variety whose stems are usually far too tannic in other regions for whole cluster fermentations) and for six months on the skins and stems (yes, you read correctly: six months!) in 1000-liter concrete tanks, followed by three months in concrete prior to bottling. The only problem with this wine and all the others from Enrico is their short supply. The Nebbiolo 1703 is yet another one of its kind, a true orig… Well, you get the idea…

Enrico Togni-Rebaioli - 2020 Nebbiolo, ‘1703’

24+ in stock