Pablo Soldavini

Photography and writing by Ted Vance.

The Argentine transplant living in Ribeira Sacra’s most deeply secluded parts, Pablo Soldavini seems to have been born to make wine. Pablo’s grandfather, Antonio Amaro, was sent from the small Ribeira Sacra town, Castro Caldelas, to Argentina in the 1930s at the age of ten to live with his uncles after his mother died during childbirth followed by years of struggle with his father and the new wife. A second generation Argentinian, Pablo grew up in the small town Punta Alta, just outside of Bahía Blanca, a medium-sized port city to the south of Buenos Aires. After primary school, he went on to study and eventually work in graphic design with some carpentry jobs on the side. The idea of returning to his grandfather’s Galician roots began to take hold, and he was simply too full of energy for the years of sitting in one place as a graphic designer.

With a magnetic draw toward his family’s ancestral stomping grounds along with an interest in the romantic side of wine, Pablo arrived to Spain in 2000 after a year meandering through Mexico (where his son and his son’s mother lived), followed by Paris, and the British city, Lancaster. He eventually settled in his grandfather’s beautiful medieval Galician hometown, atop a hill in the Ribeira Sacra with a well-preserved castle called Castillo de Castro Caldelas.

Pablo’s idea of the “romantic wine life” began to slowly deteriorate with so many industrially-processed grapes one wouldn’t even want to eat, and chemically farmed and over-cropped vineyards void of nearly all life beyond the vines. None of this end of the wine trade made sense to him, especially that just to make a few extra bucks, many small grape growers would spray herbicide and pesticide to increase their yields, even for products intended for their own table. Disillusioned, he began to work with his cousins who made vineyard work for growers in the area and worked in a more natural way. There he learned better ways to farm, and began taking courses on pruning and grape growing, and the romance was rekindled.

Pablo’s viticultural ideas are centered on respect for nature, and his mind is open to the world of possibilities in this regard. While he’s quirky and fun, and even a little antsy (well, maybe more than a little…), he’s also mentally calm and extremely thoughtful about the choices he and others make. When he’s learned something, he’s not pushy, but rather humble and is able to deliver the message to his fellow Gallegan winegrowers in a realistic and pragmatic fashion. The best thing about Pablo, aside from his natural generosity and effusiveness, is that his ambition is focused on learning things and experiencing life without a preoccupation with money. In our many conversations about wine and life, he has reiterated his disinterest in being wealthy, how he only wants to work in a way that supplies him with enough to live, while giving him a sense of meaning.

At The Source, we are infatuated with terroir but we’re even more infatuated by the people; it’s the influence of those who work the terroirs that has a greater voice than any other element of a wine. Every grape Pablo Soldavini comes in contact with seems to benefit from his touch—somehow this Galician outsider has that special instinct, and his ability to quickly understand the nature of a terroir and to coax it into breakout performance is a rare thing indeed.

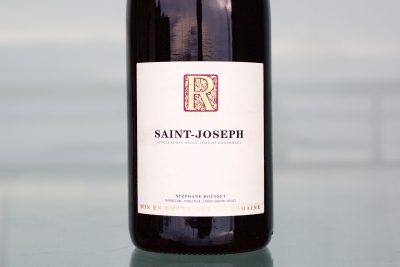

Pablo attributes much of his early knowledge to his time working with his cousins in the early 2010s, followed by his time as a former partner at the Ribeira Sacra winery, Fedellos do Couto, and others he admires for their work in the Ribeira Sacra, like Pedro Rodríguez of Guímaro, and even more so, his close relationship to Alfonso Torrento, from Envínate. The mutual respect for Pablo and his Galician compatriots is clear; even wine writers, like one of Spain’s most passionate, Luis Gutiérrez, understand how Pablo can swing the fortunes of those he works with dramatically.

Vineyard Philosophy and Practice

Once Pablo finds new vineyards they are immediately converted to organic farming, and life in this extremely wet area comes back with a vengeance—much faster than other regions. However, Pablo believes that too much of an abrupt change from conventional farming to organic can be a costly mistake, which is a shared belief with many winegrowers who have converted. The break from the vine’s dependence on treatments utillized since they were planted can shock the plant and possibly stunt the growth and production.

Pablo prefers to work with all varieties but Mencía, given the grape is not a native to Ribeira Sacra. In his vineyards, there is a good proportion of Garnacha Tintorera, Alicante Bouschet, Mouratón, Merenzao (Trousseau, in French), Godello, Palomino, Caíño Bravo, and probably some others as well, and most of the vines are middle-aged to very old.

The Cellar

Pablo employs a combination of gentle winemaking and a move away from single-variety dominated blends. The timing of the first sulfite additions depends on the fruit, with most of them added only prior to bottling. Most of the fermentations are made in open-top 1000-liter fermenters and there are no added yeast cultures, only natural fermentations. The stems are used for reds almost in entirety with an average of about 90%, and the extractions are extremely gentle and could be considered a quasi-infusion style with the grape cap only wetted a couple of times per day. Fermentations on skins last around a month before pressing and the juice spends a night in tank before transfer to either steel or barrel where they spend between six months to a year before bottling.

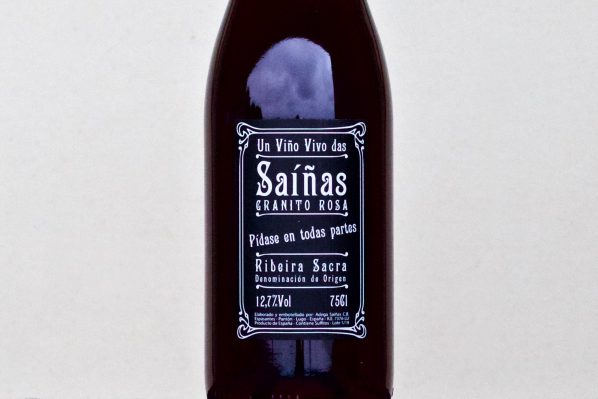

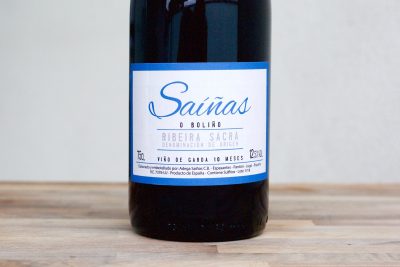

Pablo Soldavini - 2020 Ribeira Sacra, Granito Rosa, Tinto

Out of stock