Christoph Wolber (on the left) and Alexander (Alex) Götze met in Burgundy while getting their enology education at the local school in Beaune. At the same time they both worked full time jobs between some of Burgundy’s top biodynamic estates: Alex has spent nearly a decade between Pierre Morey (where we first met) and De Montille, where he is currently the chef de culture(the vineyard manager), and Christoph had some years at Leflaive, Bernhard van Berg, Domaine de la Vougeraie and Comte Armand. Shortly after they became roommates, they hatched a plan to return to Germany and start a new project in Baden, a wine region that sits on the east side of the Rhine Graben, across from and within sight of the Alsatian wine region, all in a valley that separates Germany’s Black Forest from France’s Vosge mountains.

It is difficult to imagine in a blind tasting that their Pinot Noir wines are German—no surprise considering their extensive apprenticeships in the world’s greatest Pinot Noir producing region. In fact, their top Pinot Noir, Bellen, would be difficult to place anywhere other than Burgundy, at least for anyone less experienced with Burgundy wines.

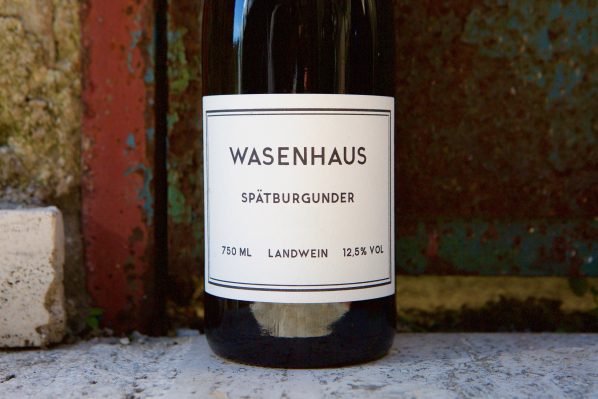

Their first vintage is 2016 and it was an incredible start. The style is as lifted and charming as it is serious. There are no tricks here, just a reverence for their fruit and a solid knowhow in both the cellar and vineyards. Their wines are crafted with clear intention; there’s no way anyone could achieve their level of quality in the first go-round by accident.

They are soft on extraction with very few punch downs during the fermentation, only the occasional movement of the cap, mostly by hand, to insure a healthy beginning. Sulfur is used judiciously (no more than 30-50 parts per million in total) and not applied until after malolactic fermentation. Their theory on the timing of the first sulfur addition is that the tannins would be more smoothly integrated than with additions beforehand, especially when there are whole cluster fermentations involved. (When it’s added during the vinification period—including primary and malolactic fermentation—the wine has more time to clearly define itself; while those that have earlier additions before fermentation potentially maintain harder tannins that could take much longer to evolve in the bottle, it leaves some of the best potential moments of the wine’s life subordinate to a potentially overbearing tannic structure.) The wines are all aged in oak barrels, but it’s too early to say what their practice will be from one vintage to the next concerning the amount of new oak—they are still discovering what works.

Burgundian monks were the first to bring the grapevines to the area, but the vines have adapted to their climate and soil types, which make them quite different than Burgundy, despite how surprisingly similar the Wasenhaus wines are to some from the Côte d’Or. However, one challenge to the grape selection in this highly industrialized area is that many of the ancient clones were replaced in the 1960s and 70s by easy to manage clonal selections that produce good yields and are more easily worked by machines. One of the tasks (and adventures) of Wasenhaus is to (re)discover vineyards within Baden with good clonal material and recoup a resemblance to the historic voice of Pinot Noir in Baden.

While Alsace is a known myriad of small geological units, Baden has tremendous diversity but on a much larger scale; it has granite, volcanic, limestone and every other soil in-between. (There is a lot already written about the influence of these soil types on wines on our website and elsewhere, and in the Wasenhaus wine pages the details for each wine will be discussed.) One unique and strongly defining geological feature in Baden that affects the shape and characteristics of their wines is the amount of löess topsoil that covers many of the hillsides with the western exposure, and more so than those facing south or east. Löess is a fine-grained and mineral-rich sandy soil (often rich in calcium) derived from rocks ground down by glaciers. This fine silt-like soil is then carried afar and deposited by the wind where it has created a surprisingly structured soil; this is due to its crystalline structure that allows it to lock into place with other loess crystalline particles. (Read more about loess here) Löess soils seem to round out of the edges of a wine and bring a sort of soft richness to its body.

The weather in Baden is closely related to its French wine producing neighbor toward the west, Alsace, and is Germany’s warmest wine producing region. During the winter and spring there is a plentiful supply of precipitation, but the weather takes a significant turn during the summer and fall and vineyards with some distance from the Black Forest become some of the driest zones in all of Germany. -TV