César Fernández Díaz

Photography and writing by Ted Vance.

What do you do besides grow grapes and make wine?

I like doing sports, like running and going to the gym. I also read a lot and attend as many seminars on viticulture as I can. My main activity is playing drums in three bands: one in English Country-Rock style (a style between The Jayhawks and Teenage Fanclub), another band is a power trio (a style like Biffy Clyro, Berri Txarrak) and a third recording drums at home, ska style (no local rehearsals).

Did you go to school for wine?

I went to the Politécnica University of Madrid to study an Agricultural Engineering degree (specializing in agricultural holdings with all types of crops and livestock management) and a Master in Enology that covered viticulture, enology and marketing. I also have another master’s degree in Business Leadership and Management Skills.

How did you get started in wine?

My mother’s family always had vineyards and produced and sold their wines. They made the wines in underground cellars and sold the wines in Aranda de Duero and directly to locals. Since childhood I helped in the vineyards and observed how my family worked with the life cycle of the vines. From a very young age I had contact with the world of wine, not only through my family, but other producers as well. When I was studying at the university, I realized that what I really liked the most about it was viticulture, but before that I didn’t have a strong interest.

What wine regions have you visited outside of Spain?

Marlborough (NZ, North of South Island), South of NZ, (reds on slate soils), Christchurch (Chardonnay, Sauvignon Blanc), Loire Valley, the south Etna side of Sicilia, Portugal’s Alentejo, Oporto, Dao, and other northern areas of Portugal.

What people or wineries are the biggest influences for you?

The longer I’ve been in the wine world, the more influences I have because I´ve tasted more things and discovered more areas.

In 2012, I started working at Bodegas Bernabeleva, in San Martín de Valdeiglesias, where the Sierra de Gredos range starts, just outside and to the west of Madrid; it’s the limit of Madrid’s community and close to Ávila and Toledo. There I worked with Marc Isart and also met the guys from Comando G. At the time, Marc was still a part of Comando G and he was the first winemaker I worked with. His ideas are still strongly reflected in the way I work today.

In 2013, I went to the south island of New Zealand for a harvest. After that, I did some work in Ribeira Sacra at Ronsel do Sil with the guys who later formed Fedellos do Couto [a partnership that initially included Pablo Soldavini, the current wine director at Adega Saíñas]. I worked in the Ribera del Duero at Díaz Bayo Hermanos in 2014, and then made my way to Comando G in 2015. From 2016 to 2018 I worked in Viña Mein (where Comando G were the technical directors) and in 2019 I returned to Comando G, where I worked until the end of 2020. During my time at Comando G I learned their philosophy and how to organize a project, despite having some different ideas about wine.

Outside of Spain, I am an especially big fan of the Jura, with white wines from Ganevat and Overnoy (I’ve not tasted the red yet), and reds from Jacques Puffeney. Burgundy wines are a major influence, as are the volcanic wines from Sicily, especially those of Arianna Occhipinti and Eduardo Torres Acosta.

In Spain there are many producers who I align with in philosophy and style. In Galicia, there is Jose Luis Mateo, from Monterrei; Rafael Palacios, in Valdeorras; the Ribeiro’s Iago Garrido (Augalevada), Luis Anxo and the team at Cume do Avia; Albamar’s Xurxo Alba and Alberto Nanclares in the Rías Biaxas; and in Ribeira Sacra, Pablo Soldavini, Laura Lorenzo, the guys from Fedellos do Couto, and Envínate. I also love the old wines from Rioja, especially Lopez de Heredia and the region of San Martin de Valdeiglesias and Gredos. In the volcanic Spanish islands of Tenerife, I’m a fan of Envínate’s wines and Suertes del Marqués, along with many others.

What was your experience with Comando G?

There were two different phases. First, I was in the winery working on the elaboration of their top wines (rumbo al norte, las umbrías, el tamboril…), then in Viña Meín (Ribeiro) when the Comand G team was consulting before the famous Ribera del Duero producer, Pago de Carraovejas, bought it. Here I specialized in vineyard recovery and changed the production line where I controlled both the winery and the vineyard. Then I later returned to Comando G as a vineyard technician.

How would you describe your wines?

I make wines I like to drink. I am looking for a wine that is like a table with four legs: minerality, elegance, acidity, and austerity in a fine, narrow and raw way. I am not looking for wines with an excess of explosive and opulent fruit, but rather more mineral-driven wines with tension and electricity on the palate—wines with definitive character.

Philosophy and Practice

Continuing with the “four legs of the table” idea (minerality, elegance, acidity, and austerity), the work of the vineyard is done with great care and detail. I always work organically, and this limits the yields and influences the style of wine I want to make. I cultivate the vine from the roots to the leaves, seeking maximum biological activity in the soil and maximum depth of roots to give the wine more character and minerality.

I work ecologically [organically] mostly because of my ethical principles. I believe that if in the fifteenth century there were vineyards without using chemical products that it can be done today, but you have to find and understand the natural resistance of the plant. The use of synthetic-chemical products alters the plant’s nature and health, which ultimately affects the quality and flavor of the grape. With biodynamics I think it is partially faith and partially real. I use plant extracts and the lunar calendar because I see that they work, but in other things I remain more skeptical. I don’t use any unnatural vine treatments outside of sulfur and copper.

As far as natural wines go, I know there are winegrowing masters who make incredible and long-lived wines without adding sulfur and there are others who make wine without sulfites but the wines end up spoiled in a short time. I like natural wines as long as they remain wine.

Sulfur in the wine

I add sulfur at the beginning of grape processing in very low doses, which is variable in amount depending on the health of the grapes. The total sulfur of my finished red wines averages between 35.2-36.5mg/L. For the rosé the total sulfur is around 65-70 mg/L because it’s naturally more delicate.

Do you like to work in a reductive or oxidative environment?

I prefer reductive to oxidative, although with Tempranillo it’s complicated because it’s a naturally very reductive variety. Even so, I like it better because if I work in an oxidative way the wines tend to have greater volume and density. I prefer finer and more elegant wines, a more Burgundian profile.

What grapes do you work with and how are they different from each other in the way they grow?

Tempranillo makes up the majority of what I work with. It has high production but a medium-low acidity. Due to the thickness of its skin, it has medium-high astringency and tannins.

Bobal is a typical red variety from the Utiel Requena (near Valencia), widely used in the old vineyards of the area, due to the grape’s lengthy cycle. The grape bunches are large and have oversized berries that tend to give herbaceous flavors. It is a very vigorous and productive varietal with medium-low acidity.

Albillo Mayor is a white grape that in the past was eaten as well as used for winemaking. It is a variety of great vigor and grows very upright, unlike the Albillo Real, which is not very vigorous and has a creeping bearing (the shoots grow down instead of up). It has small clusters with small berries and fine skin. It is a very juicy grape with a great flavor, but its only downside is that it has a medium-low acidity.

Listán Prieto is a rare red variety of Castilian origin that has almost disappeared in the Iberian Peninsula. The majority of these vines are located in the Canary Islands. It was widely brought to America by the Spanish missionaries; it’s also known as Mission, in North America, or in South American, País. The plants in the Carremolino vineyard are creeping (low to the ground) with elongated bunches and medium-high production. It produces medium-sized berries with medium acidity and a very fruity flavor.

Garnacha is a red variety with an upright growth and has problems with blooming [in CA this is referred to as “shatter”]. It produces medium sized clusters and berries with good acidity. It is a very vigorous variety that produces intense wines, with good acidity and of very high quality.

Bastardo is also known as Trousseau in France, or in Galicia, Merenzao. Portugal has the most hectares in the Iberian Peninsula where it’s called Bastardo. It is believed that it came to the area through the Douro River since it is commonly used a lot in Port wine. It has a medium acidity and is very sensitive to botrytis. The clusters are compact and have very thin-skinned grapes. The production level is average and grows in an upright position.

Pirulés is a white variety of high production with big, compact bunches and large berries. It has a low alcohol content and high acidity. It’s also very vigorous. Pirulés is the synonym of the Jaén variety [not to be confused for the Portuguese synonym for the red grape, Mencía, called Jaen—without the accent over the e]. It has a long cycle and rarely fully matures.

Vineyard topsoil and bedrock composition

I work with four vineyards that sit between 850-890 meters high, and despite being very close to each other they are quite different.

At 870 meters altitude, Carremolino has a topsoil mix of sandy loam (64% sand, 24% silt and 12% clay) and is composed of conglomerate quartzite gravels and sandstones. In the upper section of the vineyard the conglomerate bedrock is very close to the surface and the lower part of the vineyard has deeper topsoil. Carremolino is the oldest vineyard, with 30-40% of the vines pre-dating phylloxera, and the rest were planted somewhere between 1915 and 1917; the viticulture registry has it documented in 1920, but surely that date was put at random in the first wine registry that was made.

There is a new plantation I want to make a single vineyard wine from that will probably be called Torrabioso, named after its municipality. Like Carremolino, it’s a sandy loam soil (64% sand, 24% silt and 12% clay) composed of fine quartzite sands with conglomerates and sandstones and very rich in iron.

There are two vineyards that I am recovering now: La Lobera and Milagros. La Lobera, named after the municipality, is a typical Duero soil with more clay and calcareous bedrock. The topsoil is composed of silt, sand and clay with limestone marls and limestones. It was planted in the 1950s. The other vineyard, which I will likely call Milagros, also named after its municipality, was planted in 1941 by my grandfather after his military service. The topsoil here is composed of gray silt with rounded cobbles and quartzite gravel.

All the grapes from the only vineyard where I buy fruit are from vines planted in Peñaranda de Duero in the 1950s, which are ecologically certified, and its soil is a mixture of reddish sandstones and conglomerates with clay silts, carbonates and limestone bedrock. The vineyard work is done in collaboration between the vineyard owner and myself.

How do grapes from grafted old vines compare to own-rooted?

The non-grafted grapes have a finer, narrower and direct taste in the grape must (I have not made wine with only these), but I don’t know if these characteristics are due to being grafted or not; perhaps it comes from the soil. In my experience with own-rooted vineyards, the wines seem more direct and fine, with little volume in the mouth and a stronger acidity. This is the kind of result I aim for.

How is this region different from others nearby?

Here the cycle is very short; that’s why Tempranillo is grown here. It’s an extreme climate with cold winters that have frequent snowfalls, followed by hot, dry summers. There’s a very long frost period (late October through May) and even if you harvest late you can have problems with fall frost. It’s completely continental in climate, with little humidity from its annual rainfall of around 500mm. During the ripening period there is a great thermal jump between day and night, which makes grape skins thicker due to a greater synthesis of polyphenols and anthocyanins (responsible for the aromas and color). Generally, the cold winds come directly from the ocean and the Pyrenees to the north and the warm winds blow from the Mediterranean to the south.

Compared to other nearby wine regions, Rueda is colder and more humid, Arribes del Duero is warmer and with more humidity. Rioja is very similar in temperatures, but with less risk of frost and more humidity because the mountains are close and it has more rainfall from being closer to the Atlantic.

Here it is very common to have winter snowfalls, but the main problem is the spring frosts. Frost is a big problem now because there have been years with frosts even toward the end of May [after the vegetation cycle has already started]. Hail does not usually fall, but when it does it usually occurs in very dry and warm years in July. Winter temperatures are very low, and the summers are hot with an extreme diurnal shift.

Because the Ribera del Duero wine region is 115km wide (71 miles) there are a lot of differences in climate and soil between the four provinces: Soria, Segovia, Burgos, and Valladolid. In my opinion, a rough classification should be made depending on the appellation of origin, work methodology, bedrock and soil composition, and the classification of the wines themselves. I decided not to be part of the Ribeira del Duero classification because I do not agree with their ideas about which grapes are permitted or not, and the classification of the wines. My wines are classified as a protected geographical indication: Vinos de la Tierra de Castilla y León.

How many hectares of vines do you cultivate?

I cultivate 1.5 hectares of grapevines. The new addition is a young vineyard that must be grafted in 2022 and will not yield enough until 2024. I am always on the lookout to expand with interesting vineyards. In the coming years I plan to expand with new plots to produce more single-vineyard wines.

In vineyards, I look for old vines in places where the vines were planted in the area in their origins, to try to make wines that show the historic identity of the area. I look for old vineyards with stony soils and difficult conditions. It’s in these places where the plant delivers a wine of true character.

How are your wines different from others in Ribera del Duero?

In Fuentelcésped, there is a great diversity of soils and relatively exposed vineyards surrounded by wild aromatic shrubs like thyme, lavender and rosemary, along with a lot of juniper, almond and holm oak trees. It has a variety of different exposures and grades of steepness. Soils range from sandy loam, stony soils with very high active limestone, calcareous clay, etc. We are not greatly influenced by a river since there is only a small stream near the town. It is an area with a large underground water reserve; that is why there are several springs and fountains.

Regarding my wines, the main difference with most of the producers in the Ribera del Duero is that I give more emphasis to the voice of the terroir than to the barrel. I also classify the wines according to the vineyard and not the time spent in wood. I don’t produce heavily extracted, voluminous wines that need to spend a lot of time being tamed in small barrels.

A Brief Ribera del Duero Subzone Overview

In the Valladolid area there are not many very old vineyards, with one notable exception, Vega Sicilia. The vineyards in this area are typically located on plains with deep soils with good water retention capacity.

Soria has some old vineyards in very interesting places with cooler climates, like Atauta, for example. But, it’s more difficult here to find unique vineyards since there are many winemakers that have been there for a long time, like Dominio de Atauta and Bertrand Sourdais.

Segovia has very few vineyards since it is much higher in altitude and the risk of frost is greater. The red soils are mostly slate derived with a high content of clay and iron.

Burgos has a great diversity of soils, altitudes and orientations. For me it may be the most interesting area. Fuentelcésped is an example of this with its high proportion of limestone and sand, sandy-loam soils and clay-lime soils within a relatively small area.

Recent vintages

2018 had a very rainy spring and early summer vintage. While the temperatures in spring were mild, the summer was very hot and dry with an especially hot September. Despite this, the ripening progressed evenly and avoided over-maturation or strong acidity losses. It’s a vintage that gave an interesting cold profile with wines of high aging potential and very fine tannins. Carremolino suffered in the month of May from a very strong hailstorm that meant that only 300 bottles could be taken from a 0.6 ha vineyard. [The Source got half of that.]

2019 was a very hot and dry year and the plants suffered greatly during most of the growth cycle. The short maturation time gave more earthy tannins and a greater astringency. The alcohol content was also higher due to vine stress and the lengthy wait for the skins to finally mature. Acidity was lower as well due to closing stomata [the porous cells that protect the plant by controlling its exchange of gasses and water] due to the stress that resulted in the consumption of acidity.

2020 was perhaps a better vintage than 2018. It was also a cold and humid spring but with a summer of contained temperatures that were neither too high nor too low. The grapes were slow to ripen without big heat spikes or cold dips in temperature. September was mild and the plants were happy. The result is wines with good acidity and balanced ripeness. The wines of this vintage (still to be finished) appear to have a very good aging potential, electricity, character, freshness, and minerality. -TV

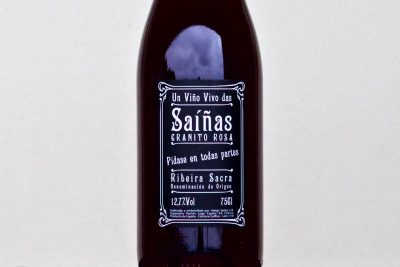

César Fernández Díaz - 2020 Espantaburros, Clarete

Out of stock