Quinta de San Michel

This website contains no AI-generated text or images.

All writing and photography are original works by Ted Vance.

Full Length Story

Inside Portugal’s minuscule insider’s wine region, Joaquim Camillo purchased the Quinta de San Michel property in 2003 and began planting vineyards a decade later in and around Colares. His vineyards span two striking and different terrains: Janas, inside the IG Lisboa, plantings started in 2013 in clay and limestone around 200 meters altitude between the Sintra Mountains and the Atlantic, and new plantings another decade later on the legendary sandy soils of Colares—some on the valley floor in planted pé-franco (true foot—no rootstock graft) meters-deep sands, others above coastal bluffs on calcareous sands and limestone bedrock facing the ocean’s salt-rich winds.

San Michel’s focus is only on historic local varieties, like the whites, Malvasia de Colares (the dominant variety in the fabled Colares white wines), Arinto, and Galego Dourado, and soon joined by the reds, Molar, Castelão, and the infamous Ramisco—the latter deeply tied to this enchanting viticultural coastline, and the only permitted red variety in Colares. Their wines from clay and limestone echo those of the great vineyards of France’s Côte d’Or but carry a maritime salty freshness, stout architectural structure, and a strong cultural distinction. Those from sand promise wines of delicate filigree, resurrecting the past glories of Colares, where Malvasia and Ramisco have thrived ungrafted for centuries.

After years of learning through experience in other wine regions across the world, Alexandre (Alex) Guedes joined Joaquim Camillo’s team, eventually commandeering the project’s direction in style and production. Now under Alex’s steady, inquisitive hand, and guided by his academic, university-trained mind (degrees in agronomy, viticulture and enology), and one step away from his Master of Wine (as of 2025), Quinta de San Michel is poised to become one of the most promising voices in Portugal’s Atlantic wine frontier and a new viticultural voice for the wines of Sintra, especially the fabled Colares wine region.

Alex’s beginnings in wine were the result of happenstance. At nineteen, while in his first year as a Civil Engineering student, he took harvest work for some extra cash in 2010 at Quinta do Vale Meão in the Douro. He expected to pick grapes but instead was placed in the cellar for three months, fourteen-hour days that passed in a blur of discovery and exhaustion. By the end of harvest, he left engineering behind, enrolled in Agronomy, and set a new course.

His training came from the cellars of the world: Quinta do Vale Meão and Malhadinha Nova in Portugal, Pikes Wines in Clare Valley, Marchesi de’ Frescobaldi in Tuscany, Framingham in Marlborough, Domaine Serene in Oregon, and Herdade Grande in Alentejo. Yet he counts the 2017 vintage at Quinta de San Michel as his first true wine—his first time holding full responsibility from vineyard to bottle. That year’s Arinto, his first crack at it alone, released in 2020, was named among the Top 10 Wines of Portugal by Revista de Vinhos. But perhaps he was especially inspired in his first year by an unexpected encounter—that of Joachim’s daughter, Inês, who became his wife! In 2025, San Michel’s Névoa de Janas wine was nominated for the best wine of the year, and later on in the year, he was in the running for “Young Winemaker of the Year.” Upward trajectory set …

Growing up in a family from northern Portugal with roots in the Loire Valley but no connection to wine, Alex claims he never had any particular mentor. But he credits Joaquim, who still drives forward at seventy-two, “With the vigor of a man half his age,” as his most constant inspiration. “I learned the most from everyone I worked with by always asking questions about everything.”

When he started with San Michel, his focus was in the cellar, where he describes himself as a taste-driven winemaker, using chemistry only for confirmation, not alteration. His ultimate goal with each wine put to bottle is consistency, and to craft wines that reflect the refreshing mists of the Atlantic and the mountains, the calcareous soils, the sands, and all things, to bring pleasure. And when not working, his interests, as of 2025, are strongly tilted toward bubbles, Bairrada (another limestone-heavy Portuguese wine region), Barolo, Burgundy, and the Loire, where Cabernet Franc and Chenin Blanc are his usual go-to wines for the table.

While strong in the cellar, he began digging deeper into the vineyards in the early 2020s, working closely with viticulturist and friend Rodrigo Martins, who advises the estate’s vineyard management and guides its transition to organics and eventually into biodynamics. Though these higher agricultural practices seem a natural progression of the minds of naturalists and perfectionists, like Alex and Joachim, the main antagonist will always be mildew.

With documented references dating back to at least 200 BC, Colares holds one of Portugal’s oldest vineyard legacies. Valued for its character since the 13th Century (but noted as far back as the third Century, the red vine variety Ramisco established itself along Portugal’s Atlantic coast, and many sorts of Malvasia began to find their way across Portugal in the 14th and 15th Centuries, with the first records of Malvasia de Colares in the area in the 19th Century. Throughout the 19th Century, wines from Colares moved through Lisbon’s ports, but it was during the phylloxera era in the late 1800s that Colares gained its broader reputation. Perhaps where the wines of the area became more relevant—maybe even mythical, with its proximity to Lisboa and virtually the sole surviving region resistant to the scourge of phylloxera, while the rest of Portugal and Europe’s vineyards succumbed to the blight. The vines of Colares were ungrafted and planted in meters-deep sand layered over calcareous clay and limestone, standing outside the pest’s reach. The vines in the neighboring areas were planted on clay, like San Michel’s vineyards now planted in Janas, and in some cases, they were destroyed, though they were only meters from the sandy soils.

Even at its peak between the 1930s and 1950s, the Colares vineyard area was modest, covering just under 1,800 hectares. By the late 20th century, it dropped to only around twenty. Lisbon’s urban expansion into this gorgeous valley, shifting wine preferences from generation to generation, and the effort and costs required to farm these vineyards compared to the vast and easily mechanized vineyards of Portugal’s nearby Alentejo contributed to its decline. A few growers maintained production throughout that period, aging wines quietly in old wooden vats while the broader wine world moved elsewhere. Most of Portugal followed international trends, with quick turnaround and inexpensive wines.

Just north of Lisbon, over the Parque Natural de Sintra-Cascais, between the Atlantic and the Serra de Sintra, Colares sits in one of mainland Portugal’s greenest, most humid oases, a land of fables that attracted Portugal’s wealthiest and its nobles and royalty. A subtropical air, with palm trees next to apple, next to protected indigenous pines (Pinheiro Manso—Stone Pine) as well as the ubiquitous invasive Eucalyptus brought from Oz to Portugal in the mid-19th Century, dense green layers unlike Portugal’s nearby drier interiors dominated by Atlantic fog and its steady moisture with temperatures that swing less than in most Portuguese vineyard zones, require close attention to mildew and rot.

As if the urban expansion that almost brought Colares to extinction wasn’t enough, Alex has observed firsthand how climate change and new pests reshape the vineyards. Frost never comes, hail is rare, but mildew and botrytis are constant threats. For example, mildew pressure in 2024 was extremely high, with fog and rain all summer, which required him to apply ten treatments. In 2025, it was also high, but he treated with sulfur and copper only six times, thanks to improved canopy management and the use of silica and seaweed treatments. More prolific in other regions, Esca is another danger, which he better manages with cane pruning instead of cordon pruning. Leafhoppers appeared for the first time in 2024. Japanese beetles have been a challenge since 2022; he traps them, catching more than 300 in 2023, fewer in 2024. (In Alto Piemonte, as of 2025, one of the closest wine regions to the origin point of its arrival in Italy, Malpensa Airport in Milan, it’s said that there is an average of about 160 beetles per vine!) Snails are another pest. Trials with different controls have failed, so in 2023 and 2024, he organized friends and wine club members to collect them by hand. They removed 200 kilos in 2024 alone, with no snail damage in 2025.

With climate change, Alex has seen it all firsthand at San Michel in less than a decade. In 2017, harvest came in October; by 2023, it had already shifted to the first week of September. 2024 was delayed because of dreary, sunless summer conditions, and by 2025, it was again in the first week of September. In normal conditions, summer days average 25–26°C, rarely exceeding 32°C, and nights 16–17°C. Fog dominates mornings, with warmer afternoons moderated by the Atlantic and Sintra mountains.

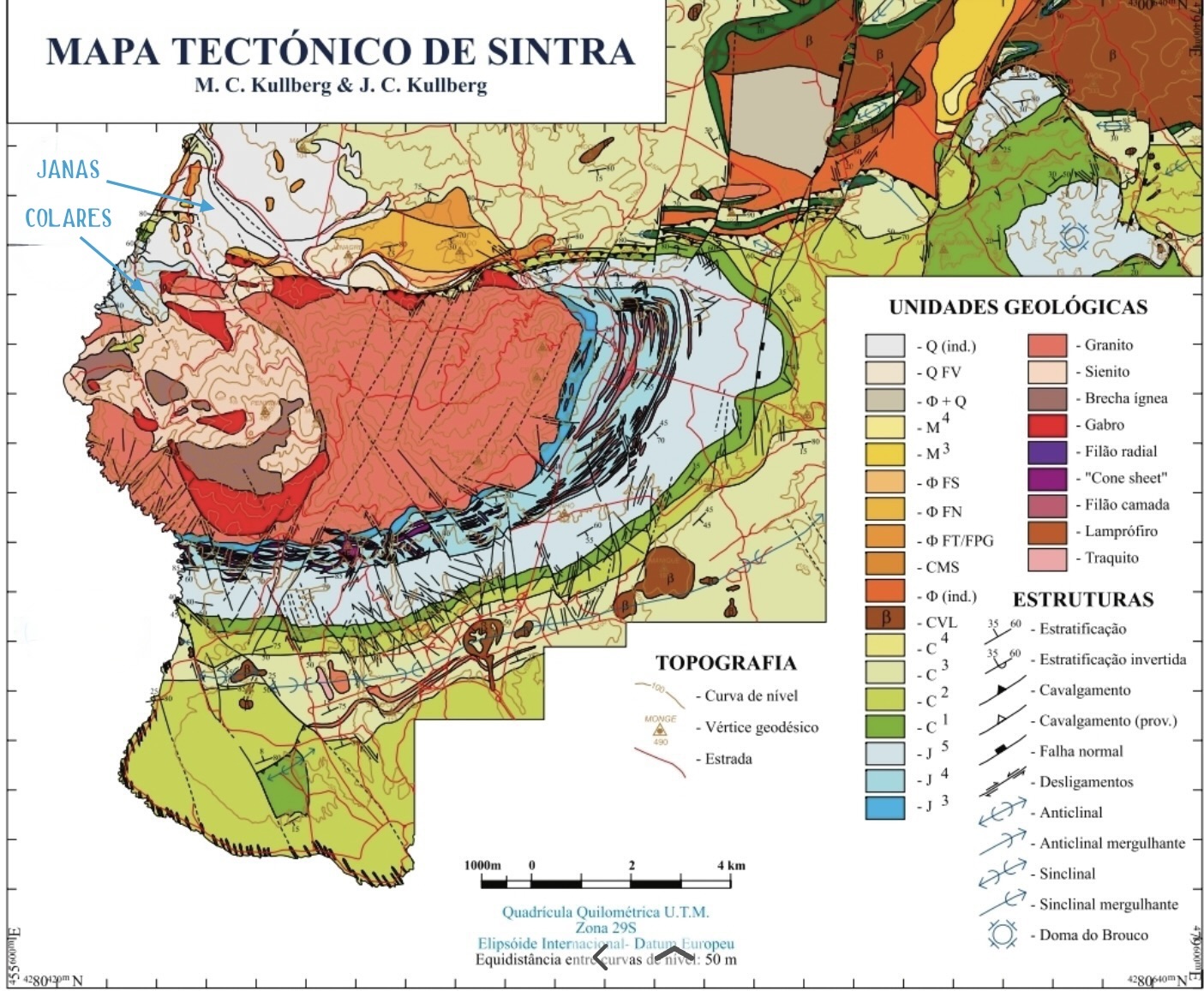

Seen as a whole, the geology of Colares and Janas unfolds in three chapters.

Beneath lies the older story: the Lusitanian Basin. Between 200 and 150 million years ago, the Vale de Colares was a small part of a massive shallow sea that laid down limestones, marly limestones, and marls, often dense with fossils. These layers form the bedrock of the vineyards in Janas and neighboring villages, and it’s the underbelly of the lower Colares vineyards that are covered with sand.

Unlike many of Portugal’s dramatic uplifts, Sintra’s wasn’t a Pangea-era event; it was tied to the later opening of the North Atlantic and the Iberian Plate hinged on its eastern end, pivoted counterclockwise away from what is today the French Atlantic seaboard: a tectonic shuffle that opened the Bay of Biscay. The Sintra uplift came toward the end of that pivot, part of a Late Cretaceous pulse of magmatism that also raised the Monchique complex in the Algarve. At the heart of the area that separates Colares from Lisboa is the Sintra Igneous Complex, born roughly 80 million years ago when magma pressed upward but never erupted; rather, it hardened into concentric igneous rock layers (imagine stone ripples radiating outward from a center): a core of syenite, rings of granite, and outcrops of darker gabbro-diorite. These weathered outcrops form the knuckled hills of the Serra de Sintra. This intrusion “baked” the surrounding Jurassic and Cretaceous beds, tilting and fracturing them into the distorted halo still visible around the massif today.

Some fifteen to twenty million years later, the African Plate’s northward push compressed Iberia against France, giving rise to the Pyrenean orogeny. But by then Sintra had already stood for millions of years, a weathered sentinel above the Atlantic.

The final layer is the most recent and the most consequential for the viticulture of Colares: sand. Over the past 2.5 million years, shifting seas and winds piled quartz-rich dunes over the limestones. Closer to Sintra, the sands are dusted with darker volcanic grains, a subtle reminder of their igneous neighbor. Here, vines must be trenched through the sand into the clays below, or—at San Michel—planted directly into sand to seek their own way down. This sandy armor is what spared Colares from phylloxera, allowing Ramisco and Malvasia de Colares to remain ungrafted when the rest of Europe succumbed. The sand protects roots but forces them to dig deep, giving the wines their firm spine and natural austerity.

Taken together, these three strata—the igneous heart, the fossil-rich marine limestones, and the restless dune sands—form the geological tapestry beneath Colares. Each adds a register to the wines: the firmness and coolness of the limestone, the power of the limestone and clay, and the delicacy of sand.

Today, San Michel’s 7.2 hectares include the 10 to 13-year-old vines first planted in Janas on calcareous clay and Jurassic limestone bedrock. The new sandy vineyards near the Atlantic, located on the lower valley floor, include Malvasia de Colares, Arinto, Galego Dourado, Castelão, and ungrafted Ramisco. Additionally, more Malvasia de Colares is grown higher up in calcareous sand on Jurassic limestone bluffs overlooking the Atlantic.

Joachim and Alex have chosen a more daring approach for some sites: rather than trenching down to the clay and backfilling with sand, they planted long shoots (ungrafted) directly a meter to a meter and a half into pure sand. The vines sent roots down and quickly grew strong. Ramisco, in particular, already had abundant bunches after the first few years. In Janas, the vines are grafted clones on SO4 rootstock (Selection Oppenheim 4); in sand, all are massale selections.

They practice plowing only once a year—after harvest and before winter rains—then they seed lupin, vetch, and berseem clover as cover crops, which hold moisture, improve soil life, and protect against erosion. Water is scarce, even when the air is constantly humid, and cover crops are more essential than ever. They use less than two kilos of copper per year, alongside silica and seaweed extracts. Vineyard densities are 5,000 vines per hectare in limestone and 3,000 in sand. The DOC Colares defines yields by hectoliters per hectare (55 hl/ha for reds, 70 hl/ha for whites), but there are no regulations on density.

Joachim and Alex are aiming for organic certification in the near future and perhaps biodynamics thereafter.

White wines from Colares and Portugal in general often age with unusual ease (as do the reds). High acidity and low alcohol lead to better whites, but indigenous varieties like Malvasia de Colares and Arinto also contribute greater phenolic structure, which provides grip and oxidative resilience.

While Arinto is not a large part of Colares’s DOC, its adaptability has made it increasingly common in the region. It handles heat, wind, and varied soils while retaining acidity and structure. In Colares, it complements the quality of Ramisco and Malvasia, widening the stylistic range under the Lisboa IGP classification. Arinto always brings a more muscular column on which other varieties can lean, a silent architecture of strength. But it is also more than scaffolding; it’s perhaps the country’s most dynamic white grape, the backbone of many Portuguese white wines.

Raw materials only realize their full potential under the hand of quality craftsmanship and passed-down experience. Not quite embracing modern techniques and tinkering, traditional cellar methods in Portugal likely reinforced this through long lees contact, larger wooden vessels, and restrained oxygen exposure. And in many cases, a straightforward, hands-off, and patient approach centered on a belief in the quality of a terroir results in the best and longest-lived wines.

Across Colares, the Dão, Vinho Verde and Bairrada, the variation of high-quality rock and soil types famous the world over for producing wines of character—igneous, metamorphic, and sedimentary rocks (particularly notable in the latter, limestones), and the mostly free-flowing Atlantic influence gives many of Portugal’s whites their characteristic tension and length.

It’s been my experience that many of the ancient bottles found across Portugal in various restaurants and retail stores were subjected to annual temperature fluctuations through inconsistent storage techniques, and though they almost always have cheap corks (ironically, in the land of cork!) many still manage to thrill—a testimony that their foundations of grape, cellar, and place were stronger than their circumstances.

The whites of San Michel have many faces, but two notably distinct ones. When these young wines are served colder than usual, they can be more easily mistaken for a broad-shouldered, muscular style of Meursault–more old-school than new: think 1990s François Jobard and the lovely stout and even hard mineral quality with that pure white Devonshire creaminess. I know the comparison is all too common, but it applies here. We’re dealing with the same geological building blocks: Jurassic limestone bedrock and white calcareous clay. The key differences are the Atlantic climate versus the continental, and varietal nuance and cultural taste; the latter, under Alex’s nose and hand, is on par with what one might see in a Côte d’Or cellar. Like many growers in Meursault, even their cellar is above ground. When the wines are served less chilled and are open for a few hours, the separation becomes more apparent, not in the shape of the wine, but in the greater expressions of the terroir.

When served on the cooler side, returning to the Côte d’Or comparison, they are closer in spirit to downslope wines rather than upslope: expansive and powerful with a dense core versus lift, angularity, and verticality, respectively, and with similar mineral qualities. Arinto, one of the world’s most talented white grapes, displays the same boundless adaptability to a variety of soil types as Chardonnay, but perhaps none more compelling than limestone and clay—consider Bairrada in Portugal, grown on similar geology. Malvasia and Galego Dourado start in the same direction, but Galego Dourado quickly splits off after the attractive reductive elements subside, and Malvasia does so much earlier than Arinto but holds the shape. Over the entire range, Alex’s gentle reductive touch in the cellar reinforces this distinctive link.

When the wines are served closer to room temperature, the differences become sharper—more cultural and varietally led. By the second day, the distinctions between texture and aromatic profile are undeniable, though the shape still holds. Arinto seems to maintain a straighter line from where it began, while Malvasia layers on the charm with the smile often hidden in the seriousness of Burgundy whites. Galego Dourado breaks away from its reductive notes and starts to pile on the spice, drawing a much greater separation.

It’s a compelling range, one that could unsettle even confident blind tasters, especially in those first hours when the wines are kept cooler and the aromatics are slow to emerge. Unlike many that mimic the Côte d’Or in style but not in substance, the congruence here is real and identifiable—at times, uncanny. This author believes the strength of the connection lies primarily in the terroir rather than the cellar work, which in turn binds these regions’ varietal connective tissue even closer together.

Perched on the mild, south-facing slopes above Janas at 200 meters, the estate’s parcels in this area share a common geological spine: medium to medium-deep calcareous clay over Jurassic limestone bedrock: a combination that tempers the sun and channels a cool mineral energy into every wine.

Across the range, fruit is whole-cluster pressed (or direct-pressed in the case of Galego Dourado), naturally fermented, and taken through full malolactic conversion. Each wine is lightly filtered at 1.2 microns (enough to clarify without stripping; not a sterile filtration) and never fined. Alex calls himself a no-lab winemaker; though he runs basic analyses, taste is what always decides.

Malvarinto de Janas, a portmanteau of Malvasia de Colares and Arinto, is drawn from a single hectare planted in 2013. This marriage of varieties brings both textured muscle and lift. It spends ten months on the gross lees, in an average three-year-old 225-liter French oak barrel, of which 15% is new—just enough to sculpt and frame without intrusion.

The Malvasia de Janas comes from a 0.6-hectare plot planted in 2015; its namesake variety expresses itself here with a quiet, saline depth and inviting spice, floral, and soft white fruit nose. It also sees ten months on gross lees, but in slightly older French oak, averaging four years of age, serving as a neutral stage for the grape’s intricate aromatics and slightly glycerol mouthfeel.

Curtimenta returns to the same hectare as Malvarinto but takes a wilder route. The fruit spends fifteen days on skins before pressing, then ages for a year in a mix of four-year-old French and Hungarian 225-liter barrels. The result is a deeper, more tactile wine, with the structure of its varieties amplified by skin tannin.

From the 0.6-hectare Arinto parcel planted in 2015, the varietal bottling is shaped by twelve months on lees in four-year-old 228-liter French oak, with this middle-aged wood offering a touch more oxygen exchange than much older barrels and a subtle roundness to Arinto’s naturally broad, potentially square disposition.

Galego Dourado, the newcomer, was planted in 2020 on a 0.3-hectare soft slope. It’s direct-pressed and fermented in steel, then given a brief six-month rest on lees in a well-seasoned six-year-old 228-liter French oak barrel. This approach captures the variety’s freshness while allowing a slow, quiet layering of texture.

They also produce a method champenois that’s out of this world. (I’m pleasantly surprised by the overall elevation of sparkling wines across Europe in places not known for them. So many are on the rise to step into the pricepoints that Champagne left on the table—well, at least for now.) Sadly, they produce so few bottles that there is nothing available for export. Maybe one day …

Together, their wines reflect both the constancy of place and the individuality of each planting, each cuvée shaped by its own small variations in vine age, variety, and élevage, but united by a shared origin in Janas’s calcareous soils and the patient, deliberate work in the cellar. With the expansion to 7.2 hectares and a new cellar in the works, production will soon grow from 15,000 bottles to 35,000–40,000. The new cellar, built with solar panels and rainwater harvesting, reflects Alex and Joachim’s vineyard philosophy of sustainability, patience, and the belief that healthy vines and careful choices create wines and a legacy that will endure.

Malvasia de Colares is the primary variety permitted in Colares whites. Marked by sharp acidity, salinity and waxy texture with occasional complexing oxidative tones as they age, and its aromas are enchanting—more effusive than stoic. In sand, these wines are lifted and fine; in clay, they are potent and more muscular. Both beguile with lifted, mineral-laden aromatics and fascinating textural differences. For this taster, Malvasia de Colares, and the many Malvasia biotypes in Portugal (which are genetically different from those of Italy’s massive stable of Malvasia varieties, making this name especially confusing), along with unsung varieties of Italy, like Campania’s Biancolella, Liguria, Corsica and Sardinia’s salty Vermentinos—to name but a few–bottled sun and smiles, all. This is the face of Malvasia in the Sintra-Colares area, though those grown in Janas at San Michel dance between serious and playful.

While Malvasia de Colares defines Colares’s white wines, Ramisco is its sole red variety. It produces small berries with thick skins and ripens late under the region’s steady Atlantic influence. The wines show high acidity, firm tannins, and moderate alcohol (typically around 11 to 12 percent). They require extended aging—often years in barrel and bottle with many excellent examples of well-aged and worthwhile Colares reds from producers like Viúva Gomes. San Michel will harvest their first own-rooted Ramisco from sandy soils in the Colares valley floor in 2025.

The Colares DOC wines of San Michel will likely find their way to our US shores around 2028 or 2029.

Quinta de San Michel - 2022 Malvarinto de Janas, Branco

Out of stock