Katharina Wechsler

Short Summary

Full Length Story

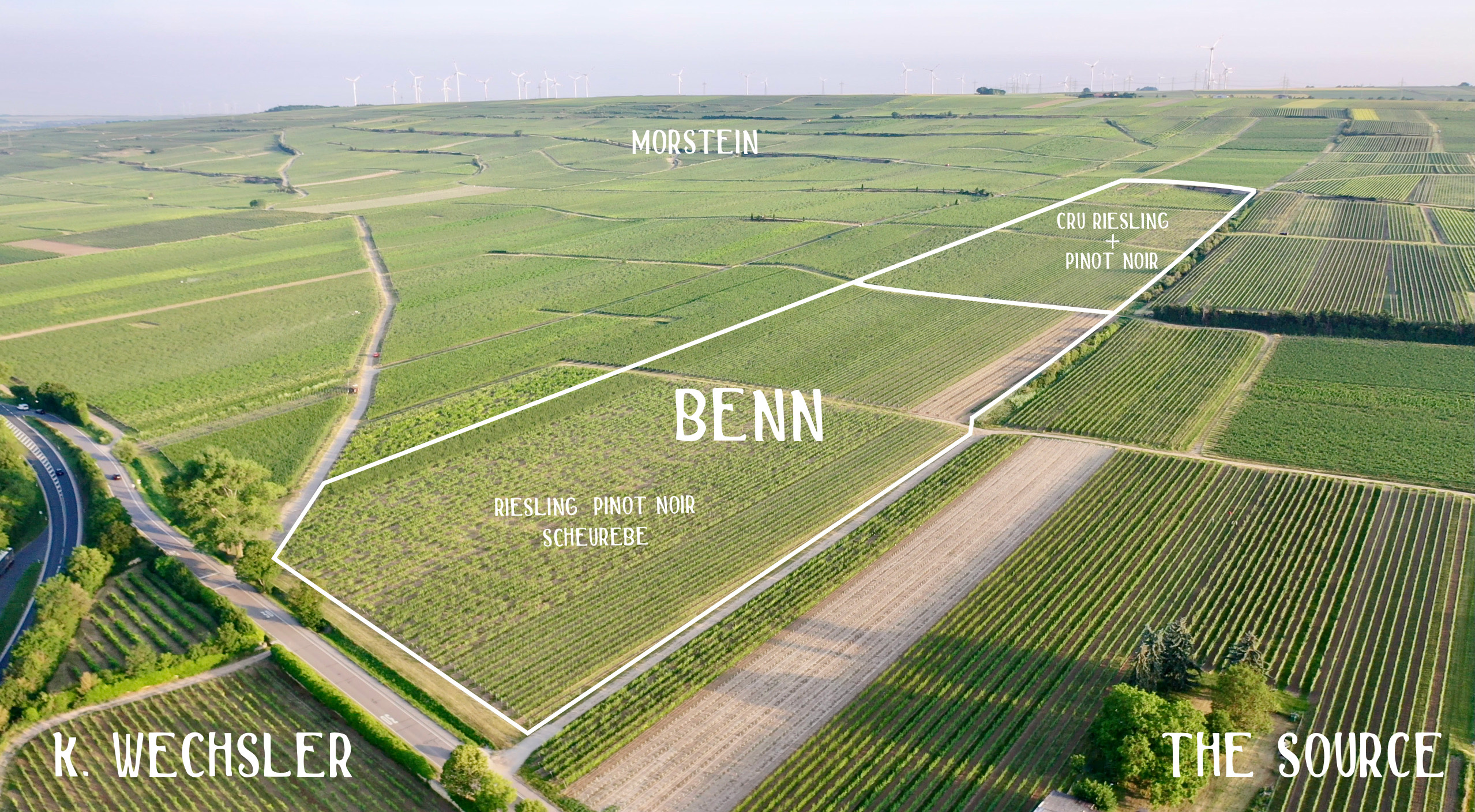

Katharina Wechsler’s enviable Rheinhessen vineyard holdings are in what may be today’s most famous dry Riesling area (mostly thanks to local luminaries, Klaus-Peter Keller, and Philipp Wittman), with highlights that include a big slab of the grand cru vineyard, Kirchspiel, and perhaps the most coveted of all recognized grand crus, Morstein. Between these two extraordinary vineyards, her family owns in its entirety a large vineyard, called Benn. Located between Morstein and Kirchspiel, lower on the slope, only the upper section of Benn is on the strongly calcareous sections planted to Riesling, while much of the lower slopes are a patchwork of many different grape varieties she loves to play with in her cellar, concocting a range of pure pleasure and fun, like her savory orange wines and other more “natural” wine bottlings. The highlight of her range is of course the classically styled dry Rieslings imbued with ornate lines and a deep, terroir drive.

We were first referred to Katharina’s wines through some local German friends and long-time followers of Klaus Peter Keller. Over the years, they put many Rieslings in front of me that fell a little short of what I was in search of, but with Katharina’s wines they nailed it. We’ve been selling many great dry Riesling producers for more than a decade, some of the highlights being Klaus-Peter Keller, Emrich-Schönleber and Clemens Busch, so we carefully examined Katharina’s wines over a three-day period of repeated tastings, and it was clear the moment they were open that we had a winner. As the days passed, they continued to deepen in complexity and refined nuances, their core power spearheaded principally by the full flex of limestone bedrock.

A New 18th Century Winery

Katharina’s approach to wine is unique. She grew up in a grape-growing environment and observed her parents’ stress during each year’s challenge, which was mostly crop losses to unfavorable weather. The Wechsler’s main source of income was producing for the bulk wine market, but in an effort to offset the unpredictability of grape growing they also cultivated grains and vegetables to better ensure annual income. The objective in grape growing was to achieve a certain sugar level (Prädikat) in order to sell for higher prices. Wine consumption was absent in the family’s daily life, and Katharina and her other siblings had little interest in continuing the family business that had begun in the eighteenth century.

After finishing high school, Katharina was off to Paris for a year to study French Literature and work as an au pair to earn her keep. She moved back to Stuttgart to study Social and Political Sciences, and in 2006 she moved to Berlin for her first job working at a German television station as a Junior Editor. However, after many weekly phone calls with her mother, she started to feel the pull to return home and help continue her family’s multi-generational, humble and ever-humbling business.

With Berlin in her rearview mirror, she was headed home. Upon her return she met with a lot of young winemakers and began to understand the difference in lifestyle between bulk wine grape growers and growers who bottled their own wines. The latter, often in a passionate pursuit of excellence, always had a greater interaction with the outside world. She began to see a meditative life of work with her hands and her mind in the vineyards and the cellar balanced with cultural experiences by way of world travel, food, wine, and access to everything from every corner of the globe—a privileged life connected to the rest of the world from her small village of Westhofen! Everything began to click; the dreamer’s dream was alive! A romantic life in agriculture could be achieved! But first things first…

2009 was to be her first season and she attended winemaking school in Oppenheim at the same time. Prior to acquiring her degree in 2012, she worked harvests for Weingut Gutzler in 2010, and the following year for Germany’s rarely disputed dry Riesling king in the next village, Klaus-Peter Keller. They share many of the same vineyard plots, particularly inside the extraordinary Kirchspiel and Morstein crus. Katharina explains that Keller taught her about finesse in limestone-driven white wines, and the importance of trinkfreude, the “joy to drink.”

Little by little, Katharina found her footing. She’s inspired by the racy, high-acid style of Keller, but her wines speak more softly and with a slower burn. One of Riesling’s many exceptional qualities is its ability to remain deeply complex while expressing a magnificent multitude of faces. Dry Riesling can be thunder and lightning with intense, multi-colored sunsets and sunrises, like Keller’s masterpieces. Katharina’s, by contrast, delivers contemplation under a fresh moonlit countryside with the shimmering orange glow of lights on the horizon and the flicker of white fire of the night’s stars above.

Katharina’s Style

Years away from her immersion in the bustle of Paris, with its immense history, passing the days with French poetry and literature followed by the excitement of television in Berlin, brought Katharina to engage in wine differently. She approaches it with eyes wide open to the wider world, and to spend time with her is a feast of ambiance, conversation, food, and, of course, wine; but wine is not the main event, rather a stimulant for a more open encounter. Wine without ambiance means less, and she sets the stage for each moment—to show how she likes to enjoy wine. It could be a terroir tour in the vineyards while drinking wines rendered from what lies under your feet, or Sexy MF, her Cloudy by Nature Pinot Noir rosé, in her flower garden as it wafts similarly beautiful aromas; all after a quick dip for your swollen feet after a vineyard tour in the cool and serene spring next to the garden.

One of Katharina’s many great interests and regular activities involves jet-setting her way around the world to enjoy the local food and drink, and she wants nothing more than to bring the taste of the world to Westhofen! A summer meal at Wechsler is no ordinary German feast; it involves freshly baked bread that reminds me of those in a Saturday morning French farmer’s market, fresh-made herb butter, baskets of lemons and limes for accenting, mounds of garlic, garden-fresh tomatoes, fresh-cut delicate lettuces, and green herbs readied for salads and dressings, or mortared for whatever comes off their grill, fueled by gnarly, old-vine stocks. The fare is fresh and light, colorful and aromatic, invigorating and full of life. For Katharina and her partner, Manuel, organic is not only the way for their food, vineyards and wines, it’s also a way of life.

Vineyard Culture

While viticulture was trending toward natural and organic farming prior, her pursuit to certify it began in 2018, making 2021 the first “official” vintage. She wasn’t entirely sure about certification, but she started Biodynamic practices with the 2020 vintage. She views the holistic and preventative approach of biodynamics as an attempt to build the plants natural immunity against typical fungal diseases and whatever new climatic challenges may bring.

When asked how her vineyards are different from others in the area (even those who have been working organically or biodynamically for some time), Katharina says that hers are a little more free to grow as they want and need to grow, rather than being perfectly tidy and rigidly sculpted. Each vine’s growth is based on individual needs, and to keep them all in the same uniformity may be more for the ease of the grower but not necessarily for the benefit of the plant. Soil amendments are limited to additions of their own compost from horse manure, grape pomace, and green waste. Annual plowing is made not only to manage the overgrowth of grasses and weeds but to mix in the more than thirty different herbs they plant between the rows to enrich the soil with nutrients. The augmentations toward more natural farming have resulted in lower yields and sometimes smaller berry size. Katharina cautions that while most of the time this is the case, every year is different. The most noticeable result is the greater overall natural balance of each plot, which naturally shows up in the wines.

The Grapes

The sixteen hectares of Weingut Wechsler are broken down into approximately one-third to Riesling, another third to Burgundian varietals, like Chardonnay, Pinot Blanc/Weissburgunder, Pinot Gris/Grauburgunder (known as Pinot Beurot in Burgundy), and Pinot Noir/Spätburgunder, and the last third to Sauvignon as well as many productive regional varieties historically used to increase yields (and profits) for bulk wine producers: grapes like Silvaner, Scheurebe (a cross between Riesling and Bouquette), Müller-Thurgau (a cross of Riesling and Madeleine Royale), Dornfelder (a cross of Helfensteiner and Herodrebe), Huxel (a cross of Chasselas and Muscat de Saumur), Faber (a cross of Chardonnay and Müller-Thurgau), and Kerner (a cross of Riesling and Trollinger/Schiava).

While the first two thirds of her vineyards mentioned are the cornerstones of Katharina’s classically styled range of wines, the last third is slowly losing ground to replantations of other grapes, but not without a lot of experimentation and fun first. It’s this last third that brings to Wechsler’s portfolio such an extensive and stylistically diverse range. There may be some undiscovered magic in these crazy grapes, and she has been greatly inspired by the natural wine bars of Paris and Copenhagen and the global glou glou trend. Germany is far behind in this style, but Wechsler is not. In fact, she may become one of Germany’s most important producers for their own generation’s trinkfreude.

The Climate

Rheinhessen is considered a continental/Mediterranean climate, and this of course means relatively hot summers and freezing cold winters for a wine region. The surrounding hills are low, and are referred to as the Alzeyer Hügelland (translating to the low hills of Alzey). They rise to no higher than 350-meters, with Westhofen at 120m, and Katharina’s highest vineyard, Morstein, starting around 180m and peaking at a little over 220m. However, toward the north, the more pronounced reliefs of Hunsrück and Taunus ranges (the latter range, home to Germany’s most historic dry Riesling region, Rheingau), curb the colder northern winds, imparting in the areas inside the Rhineland-Palatinate district (the interior German state with most of the country’s wine regions) more moderate cold temperatures. In Westhofen, Katharina has witnessed winter temperatures as low as -17°C (1°F) and summer extremes as high as 42°C (108°F). The harvest season diurnal range can be between a 12°C-25°C shift from day to night. Annual precipitation levels are around 700mm/yr (27.5 inches), and peak summertime daylight on June 21 is a whopping sixteen hours and eighteen minutes. For context, that’s just short of twenty minutes more than the similarly exposed (flatter) Chablis sites, like the Montmains premier cru, but far less actual direct sunshine than what would strike Côte d’Or’s prime white wine real estate due to the early sunset behind its more abruptly sloped, eastern-facing hillsides. The Rheinhessen’s vineyards receive as much direct summer sunlight as any wine region in the world due to its open exposure and far northern location.

Limestone and Riesling: An Unanticipated Perfect Match

Limestone may be responsible for the world’s most recognizable and dominant European wines of the last century. Its unique balance of power and refinement, palate-filling and finely textured wines are ubiquitous, even if you didn’t know some of your favorite wine regions are limestone terroirs. Prior to all the geological hubbub and the influence of rock types on their resulting wines, the global market was unknowingly dominated by the accessibility, freshness and depth of limestone-powered wines. Think about Europe’s most dominant fine wine categories of the previous three decades prior to the last: In France, the Loire Valley with Sancerre and many of the famous Chenin Blanc terroirs, Champagne, Chablis, Côte d’Or and the rest of Burgundy (excluding the Beaujolais crus, while including much of the rest of Beaujolais’ southern section), Châteauneuf-du-Pape and all its Southern Rhône satellite appellations, the eastern side of Bordeaux with Saint-Emilion and Pomerol, much of the Languedoc and Provence; Italy’s Barolo, Barbaresco, Chianti and Chianti Classico, Brunello di Montalcino (the latter three regions not particularly dominated by limestone, but it stands as a major contributor), Friuli-Venezia Giulia and the Veneto; Spain’s Rioja and Ribera del Duero. That list of wines made the biggest waves of that time with higher-end European wines (outside of left-bank Bordeaux) and the link between limestone and their overarching success can’t be ignored. Limestone often imparts a broader palate sensation to its wines (as do some volcanic rock types) while other bedrock types, like igneous and metamorphic, tend to have sharper or more rigid textural lines. All of this, of course, is a personal take on how rock type may influence palate-feel, but I don’t stand alone in this sentiment.

Limestone’s interaction with Riesling is somewhat rare in the vast expanse of Germany’s wine regions. I can’t find this one written passage I swear I read many years ago, but I remember (or at least I think I do) that in my earliest years of fascination with Riesling a piece asserting that limestone terroirs were less ideal for Riesling—seemingly a far fetched idea with Alsace’s many historic limestone Riesling spots, most notably Trimbach’s unanimous Alsatian category leader, Clos Ste. Hune. For newer comers to the wine business with an interest in dry Riesling, this may seem absurd and impossible to fathom, what with today’s monstrous success of the Rheinhessen’s luminaries and their game-changing wines, but to include the words “limestone” and “great dry German Riesling” in the same breath seems to be a relatively recent phenomenon for Germany, at least in my time.

After World War II, the limestone regions of Rheinhessen had already found their place producing bulk wines in mostly flat fields that were perfect for mechanization. At the time, the region’s only real high-quality producing areas were along the Rhine River on mostly red slate-derived bedrock and soil (most famously the vineyard, Roter Hang, in Nierstein und Nackenheim) and perhaps others on other metamorphic rock formations. The rest was considered rotgut, a provisionary commodity dosed with sugar and alcohol, named Liebfraumilch. It’s no wonder that the young Katharina lost interest in grape growing early on. If you see from a young age that your region is producing the bottom of the barrel and every year your parent’s stress levels and physical toil are through the roof, why would you want to stick around for that?

Due Credit

With all of today’s fuss about the Rheinhessen’s extraordinary dry Rieslings, there is no greater irony than the region’s historical reputation of bulk wine production and of the poorest quality in all of Germany for the last hundred years. To now be at the top of the heap for dry German Riesling, gratitude is owed to the extraordinary vision, research, and craftsmanship of mainly the Keller and Wittmann families. They explored, unearthed, and invested their lives and tremendous resources in these extraordinary vineyard sites. They knew through historical records that their vineyards had been celebrated centuries ago (and even Liebfraumilch was a former glory of German wine before it was bastardized), but it had been nearly forgotten for generations before their time. While I would hardly call their influence a mere spark, but rather a raging and passionate fire that the wine world was obliged to recognize, it all started with them. Their impact continues to ripple through the industry, inspiring the arrival and rebirth of many new and exciting wineries along this curious and completely unique strip of limestone, including that of the young Katharina Wechsler.

Limestone in Southwest Germany: A Quick Geologic Tour

Wherever there is limestone, there was water first. During the Alpine orogeny (mountain-building event), a massive graben (geological structure shaped like a ditch, produced by tectonic processes) known as the Rhine Graben, separated today’s Vosges Mountains in France and Germany’s Pfaelzerwald to the north, from the Black Forest (Schwarzrwald) Mountains, creating this massive graben that spans as much as 60 kilometers from east to west (with an average width of around 50 kilometers), and some 350 kilometers, or so, from north to south. Within this long valley where the Rhine River begins its journey from Switzerland, passing through four other countries (Liechtenstein, Austria, Germany, France) making its journey’s end on the coast of the Netherlands, can be found the French wine region of Alsace, and the German wine regions of Pfalz, Rheinhessen, Rheingau, most of Baden, and just a hair of eastern Nahe.

A little more than sixty million years ago (at the start of the Cenozoic period), what is today’s Rhine Valley acted like a seaway connecting mainly the North Sea and what were called the Tethys (the location of most of today’s Mediterranean Sea) and Paratethys oceans. Eventually the Mainz basin, the Rhine Graben’s northernmost section today, would become a bay with shallow waters that collected the skeletal remnants of various animals and plants rich in calcium carbonate that would create what are today’s limestone hillsides found in the Rheinhessen, and also many parts of Pfalz, Baden, and likely that very special Trimbach vineyard, the Clos Ste. Hune.

What’s loess got to do with it?

Sing it, Tina! Limestone bedrock and topsoil may be the biggest geological feature for these dynamic Rieslings, but the second-hand player is loess, also commonly written löss, or löess. In short, loess is wind-blown, silt-sized particles (referred to here as aeolian silt) created by the glacial grinding of rock during the recent ice ages into a fine enough grain to be swept up into the sky and transported over hundreds, and in some cases thousands of kilometers. Here, the loess is rich in calcium carbonate, likely due to the grinding of limestone rocks in the Alps. A grape variety that often expresses a more vertical profile in bedrock and soil types of metamorphic and igneous rocks, these vineyards rich in both loess and limestone may be one of the keys to the broader horizontal character of the Riesling from these parts—the other main factor may be the summer sun. A predominance of loess soil makes for even slightly fatter wines with a more upfront appeal once uncorked. The water retention capacity and the nutrient richness of loess, in addition to limestone, is another major contributing factor, which helps to ameliorate the dehydrating beatdown of the summer sun.

The Crus: Benn, Kirchspiel, and Morstein

Benn, the family’s tiny monopole vineyard site, has perhaps the most diverse plantations of all her vineyard parcels. It’s her biggest vineyard section and has the greatest variation of bedrock and topsoil as well as grape varieties. The warmest of Katharina’s three important crus, it’s composed mostly of loess topsoil in the lower parts that sit as low as 120m, and limestone in the upper part, peaking around 160m. The loess topsoil is known as loess pararendzina, described by the Rheinhessen.de website as fertile, deep, light loam, clayey silt, with very good water storage capacity, adequate aeration, nutrient-richness, calcareous soil with moderate warmability, good rootability, and with a high growth potential—what a mouthful! All of this sounds perfect, right? But Katharina’s task here is not to get the vines to grow more, rather to find solutions to reach balanced growth, particularly in the lower sections. Quality Riesling is preferential to suffering, which is why it is in the lower sections where much of the non-Riesling vines are planted. Its 50-year-old Riesling vines, particularly those used for Wechsler’s top-flight trocken bottling, are planted in limestone bedrock and limestone and loess topsoil toward the top, not too far away from the bottom of Morstein. The young Riesling vines there were planted in the early 2000s and make up 50% of the entry-level Riesling Trocken (with the remainder 20% from Kirchspiel, 20% Steingrube, and 10% Aulerde); it’s a dynamite wine that easily matches all comers in the same price category for dry German Riesling. Notably, the old vines produce an annual average of nearly 25hl/ha (1.33 tons/acre), and the young 65hl/ha (4.33 tons/acre)—almost a 1:3 ratio; you can imagine which vines are used for the top wine…

The quality of Riesling generated from Benn is noteworthy, but there’s no doubt its current highs at the Grosses Gewächs level (while it isn’t classified as a GG wine, nor is Katharina in the VDP) are not yet the same level as Kirchspiel and Morstein. That said, Benn is still being discovered by Katharina. A terroir is what it is, and we can’t change that (if, of course, we want to respect the natural setting of the terroir!), and expecting a wine to have a similar level of expression through the same means employed with other neighboring vineyards is not always the right route. Take Côte d’Or vineyards, for example, where winegrowers change some vinification and aging methods in the cellar of one parcel’s grapes from the way it’s done in the neighboring parcel. To this taster, Benn produces a substantial Riesling and it has very impressive moments, especially with more time in the glass. When the others shine so brightly in their own individual way, Benn has been upfront but somehow still a slower burn. The material for potential greatness is unquestionably in the wine’s interior, but it often needs a little more time open and perhaps more cellar aging too, to fully express itself on a level similar to Kirchspiel and Morstein.

Making excuses? Not really. Sometimes with neighboring terroirs, we in the wine business split hairs. The upper section of Benn has major Riesling potential—as demonstrated by Katharina’s most recent iterations—but lacks the track record and understanding of other great surrounding crus because, by comparison, it’s only been seriously explored for high quality wine since Katharina came home, and the Wechslers have owned it in its entirety for a long time. Kirchspiel and Morstein have had extraordinary minds and masters of the winegrowing craft working to unlock their magic for decades—both Keller and Wittmann own parcels in these sites, and they are open to share their knowledge and experience of working them, as well as the wines in the cellar.

Kirchspiel is a great vineyard and screams its grand cru status (Grosses Gewächs) upon opening. It’s always readier out of the gates—in the range of other growers as well—and for many reasons. Shaped like an amphitheater facing toward the Rhine River (but still roughly five miles away by air to the closest point) with its southeastern exposure an average of around a thirty percent gradient, its bedrock and topsoil is composed of clay marls, limestone and loess. It’s a warmer site than Morstein because of its lower altitude (between 140m-180m) along with the curvature of the hillside that allows it to maintain greater warmth inside this small but sheltering topographical feature from cold westerly winds. Katharina has three different parcels in this large vineyard with reasonably good separation, giving the resulting wines a broader range of complexity and greater balance.

The three different parcels were planted between the year 2000 and 2015 and the average yield between them ranges from 40hl-60hl/ha (2.67-4.0 tons/acre), with some of the fruit slotted for the Estate Riesling Trocken and the Feinherb Riesling Trocken, the top quality lots (which doesn’t always have to do with yield, but rather specific parcels that naturally excel beyond others) for the Kirschspiel Trocken, and the difference for the Westhofner Riesling Trocken and the Estate Trocken and Feinherb Trocken. The youth of these vines is on display with the resulting wines and their vigorous and energy-filled, fruit-forward personalities that balance the mouth-watering, mineral-rich palate textures and aromas. Kirchspiel is a leader in the range of all who have Riesling vines in this gifted terroir, and it’s considered one of the country’s great dry Riesling sites.

Morstein, Rheinhessen’s juggernaut limestone-based, dry Riesling vineyard is—even with vines only replanted in 2012—the undisputed big boy in Katharina’s dry Riesling range. It’s one of the vineyards that first made Klaus-Peter Keller famous (I believe the other was Hubacker), and from what KP told me some years ago, it’s also the principal location for his G-Max Riesling (of which he won’t openly disclose the precise location now because some years ago some overindulgent visitors were made privy to its location and later stole a bunch of the grape clusters!). Katharina’s Morstein vines are massale selections from the Mosel and have smaller, looser clusters with naturally low yields, even from the young vines.

A mere pup by the standard of vine age, Morstein is formidable. And while it’s not as flashy out of the gates, it picks up serious power and expansive complexities that seem to know no end. There are many top wines in the range of the world’s great producers that behave in a similar way. Take the slow burn once the corks are pulled on Armand Rousseau’s Chambertin compared to the all-out charge of their crowd-pleasing Charmes-Chambertin; Cavallotto’s Riserva Barolos, with the long-game, Vigna San Giuseppe, that trounces after hours open, versus the upfront Vignolo with a smaller window of greatness; Veyder-Malberg’s greatest pillar of Riesling purity and deep power, Brandstadtt, next to the ready-to-go Bruck; Emrich-Schönleber’s regal Halenberg on blue slate versus the friendlier Frühlingsplätzchen spurred into immediate action from its red slate. Morstein is no rapid takeoff F-15 fighter jet with instant supersonic speeds of near 1,900mph. It’s a rocket ship with a slow initial takeoff and a steady climb that reaches 17,000mph before entering orbit.

Morstein faces south and rises to a high plateau of around 240m with a 20% gradient (a slope hard to understand from a distance but more evident when standing in the vineyard), all on limestone bedrock. The topsoil is referred to as terra fusca (black earth), a soil matrix of heavy brown clay. Its low to medium topsoil depth (by vinous standards), combined with limestone fragments from the underlying bedrock makes its ability for water storage more limited than Katharina’s other main sites. Its root penetration into the subsoil is also a more difficult challenge, giving the Riesling vines the much-needed stress to regularly pull off peak performance. These young vineyards yield between 35hl/ha and 55hl/ha (2.3tons/acre to 3.7tons/acre), relatively low numbers for young vines that demonstrate Morstein’s spare vineyard soils.

Cellar Details: The Rieslings

One of the most rewarding characteristics of Katharina’s wines is the simplicity of the cellar work. The vineyards speak for themselves without massive unnatural alterations such as excessive fertilizations and other amendments that clumsy up the wines with unnecessary and blunting power. All of her wines are fermented and raised in stainless steel on the heavier lees without bâtonnage (the technique of lees stirring to further flesh out the body of a wine, among other effects) and bottled when they’ve reached their optimal moment. Skin maceration is dependent on the year and the specific parcel, ripeness level, and acidity, and can range between four and sixteen hours—crushed by foot. Pressing is done with the whole clusters, and the grape must settles for 6-24 hours before racking to another tank with the must’s more clean solids. Fermentations are natural and sometimes take up to ten days before starting; if necessary, neutral cultured yeasts may be used for stubborn grape musts. The maximum fermentation temperatures reach up to 24°C (75°F), and she prefers warmer ferments to highlight strong terroir elements earlier on while curbing what could be excessive fruitiness from colder fermentations. The wines finish to full dryness in two to sometimes more than six weeks after the start of fermentation. The entry-level Rieslings (Estate Trocken, Feinherb) and Scheurebe Trocken are bottled in early spring, and the others “when they are ready”—usually between the end of spring and the end of summer. The first sulfite addition is made in the winter and again prior to bottling. The wines go through a gentle, non-sterile filtration to ensure they are clear (the market is not too into cloudy dry Riesling—yet…), and there are no finings.

Cellar Details: Non-Riesling, Classically Styled Wines

Wechsler has another line of wines, in both still and sparkling. We can’t import all twenty in her range (yet!), so we picked our spots. There are dry versions of Silvaner, Pinot Blanc, Pinot Gris, Pinot Noir, and Scheurebe. One of the many highlights is the Scheurebe Trocken, a straight-shooting, glorious version of this variety that captures its better qualities while leaving behind the often-exhaustive aromatic characteristics. Its acidity is electric and engaging, and its general characteristics are high-toned. It flaunts the limestone terroir with the same class as the Rieslings from the vineyards it comes from, Benn and Kirchspiel.

Cellar Details: Cloudy by Nature

On the flip side, the Cloudy by Nature wines have their own personalities and quite a contrasting approach—if not completely opposite—to the classical dry Riesling range. They demonstrate Katharina’s openness to the world and what can be discovered in today’s less judgmental wine community, along with some incorporation of her interest in music—hence the names that play on musical references, like Naughty by Nature, the name of an American Hip Hop trio—sorry to have to spell it out so clearly for those of you who find it obvious… The grapes for these wines are grown either in the lower sections of Benn, some from Kirchspiel, or in Clos Catherine, just across the road from Benn, in an unwalled vineyard, home to some of the Wechsler family’s oldest vines and non-Riesling biotypes.

Cloudy by Nature is the party range—the glou glou, the drink-it-don’t-think-it, or the focus-less-on-the-wine-in-your-glass-and-more-on-the-person-in-front-of-you wines. Her Pet Nat Silvaner “Fehlfarbe” is a rough German translation of “wrong color,” and implies “neither white nor red,” but orange. The name’s musical reference is an 1980s quasi-punk German band called Fehlfarbe; I never thought about it, but after listening to some of their music for context, German works quite well with the abruptly edgy yelling in punk rock. It’s grown in Clos Catherine from the vines planted in the mid-1970s. Another orange wine is the Scheurebe “Fehlfarbe”—an experiment gone utterly right. Equally fun as it is serious and complex, judging by this wine, Scheurebe has a natural talent for orange wine with its intrinsic bright floral aromas in classically styled dry wines that metamorphose into beautiful dried floral and dried herb tea notes, and the suave but only slightly grippy texture of a second-brew tea. Then there’s Sexy MF, an unapologetically playful name that plays on the title of a Prince song (with curvy, purple, Prince-inspired lettering on the label, just in case this isn’t obvious at first glance), but it’s also a play on words of the loose-bunch, Swiss-origin, MariaFeld Pinot Noir clones that make up the fruit for this wine, as well as her other still Spätburgunder. Sexy MF is well… exactly as the name suggests. Delicious and addicting at first sniff and gulp, this wine originating in Benn requires great willpower to avoid guzzling. However, behind its intoxicating pheromonal spell, it has serious and contemplative trim. The only problem with all of Katharina’s Cloudy by Nature wines is that they are delicious and in very limited production!

All the Cloudy by Nature wines are all made in stainless steel, like the rest of her range, and they are finished with very low sulfur doses and bottled with intended turbidity. Katharina says that they are bottled after they finish malolactic fermentation to not be filtered or over-sulfited to stop unwanted fermentations. As would be expected, they are naturally fermented, unfined and unfiltered.