We’re still in renovation purgatory with our countryside rock house (lifelong dream number one), a Notre Dame de Paris-level timeline that started only months before the pandemic hit. Even with such a long way to go, we’re still happy living in Europe, though a process like this will test even the most patient and optimistic saint. I’m mostly the first two of these, but certainly not the last.

Perhaps the top European perk for us Epicureans is the availability of the best ingredients. My wife and I miss a lot of things about the US, and some farmers’ markets can equal some of ours, but Europe is generally tough to beat. As I write this in late August, the spectacular taste and color of the figs in Spain are dizzying and they cost the equivalent of only $2-$3 per pound. Chanterelles are $7 a pound (dried to the point where a full produce bag weighs that much), fresh sardines are $5, mackerel $4, and on and on.

Some European countries simply dominate certain food categories. The Usain Bolt of cheese and poultry is France: no one else is even close. The battle between seafood and fish is without a clear winner, but many believe the raw product frontrunner in Western Europe is Spain. The most compelling argument that tips the scale in Spain’s favor outside of the three Atlantic fronts and a thousand miles of Mediterranean coastline is what comes from Galicia’s Rías Baixas (though the endless variety of Sicilian and Sardinian fare would be two of Italy’s many parries); the uniqueness of the four Galician estuaries (rías) offer marine life a plankton overdose, leading to monstrously sized and extremely flavorful goods all the way up the food chain.

The salt-cured food category echoes the Federer, Djokovic, and Nadal debate: sausage is anyone’s game, and all the contenders are as different as tennis’s Big Three. Spain wins on land with cecina and jamon like France does with cheese. Italian anchovies can match the Spanish in taste, though Spain has many more high-end producers in Cantabria that market themselves well. Like all anchovy-producing countries, the disparity may be attributed to their cultural approach. Spain takes anchovies more seriously than any country as a stand-alone food, a sort of luxury good meant as the center of the plate it adorns. Italians see anchovies as more of a potent support in their orchestra of ingredients for a million different dishes, and it’s rare to see them as the dish alone.

Iberico pork (pictured below), Galician beef, lamb, goat and cochinillo (suckling pig) are legendary in Spain. Spain is so far ahead of the European pack on four-legged fare there is almost no chance for a successful coup. Indeed, there are always outliers in Europe—individuals or small zones that do it perfectly—and arguments for other non-European countries, but Spain as a whole on meat is what Babe Ruth was to baseball.

The next top perk for epicureans interested in vinous exploits is the European restaurant wine list. Prices in most restaurants lacking Michelin stars are still appropriately marked up because growers know where their wines are shipped directly in Europe and they visit their clients all over the continent. For example, French growers understand that in places like Paris, Bordeaux and Lyon the cost of living, rent and labor is much higher and have far more affluent customers passing through. They also expect to see higher markups because restaurants want to keep exceptional wines in stock long enough to maintain their reputation for having a great list.

The countryside is the best place to drink. Prices are much lower because the owners know their top growers on the list may drop in for a visit, especially if they’re local. And if they are in fact gouging with big city margins, they may get a reduction of or lose their entire future allocations. I imagine that few growers are happy to see their 15€ wine on a countryside list at 200€ per bottle.

While Europe wins on restaurant wine lists, it doesn’t always win in the retail market. A good fine wine store in the US is often a one-stop shop for wines from all over the world and the others are very local, though that’s changing with the addition of the online marketplace. The access to the many now unaffordable growers, like Chablis global megastars Dauvissat and Raveneau, are the same jaw-dropping prices online in Europe as they are anywhere in the world.

Twenty years ago, the wines from Dauvissat and Raveneau were easier to attain at a decent price. Even if they were gray marketed by US retailers at the time, they were marked up only a touch more than what the official importer charged. This duo of Chablis royalty was once slightly obscure and mostly known to insiders. Kept relatively quiet among the wine trade, they offered enlightening grand cru and premier cru experiences for low-paid wine professionals and wine lovers without Montrachet prices. But if you want them stateside, that markup is now more of a shakedown. The last bottle of Raveneau I ever bought upon release in the US from their official importer was a 2010 Montée de Tonnerre at LA’s Silverlake Wine, where it sat on their shelf for anyone to buy for around $100—today, the 2019 and 2020s are online starting around $500-$600. These days it’s only window shopping in the States on the Raveneau and Dauvissat front for most of us. And I marvel at the prices on lists and wonder why people think wine—a bottle of fermented grape juice—should command so much, especially if they started from the cellar door for far less. Romain Collet, who’s close to the Raveneau family, always shoots me a smirk when we speak of Raveneau and the absurdity of second-market prices because he knows his ex-cellar prices are the same as theirs.

I think we in the business can only blame ourselves for letting our insider wines go to only the highest bidders now. We aggrandized these special wines on social media to sell them (and ourselves) more effectively and to make a few more bucks on tiny allocations. And in these pursuits, we priced ourselves out of the game. I remember how disheartened I was when one budding wine retailer boasted to me that they were converting all their Bordeaux drinkers to Burgundy—like they were doing all of us a favor. The famous Bordeaux enologist Emile Peynaud said something like, “People drink what they deserve.” Maybe in his time, that was truer, but this catchy snark hasn’t aged well with big money willing to pay any price for certain wines.

Before the pandemic, there were still a lot of deals to be found with hard-to-get wines from European retailers, but those days are over now too, at least for the elusive ones from France and Italy. The most recent batch of goodies I snapped up before the prices went bonkers on every inevitable name destined for that list were those of Lamy and Lafarge. I had a few good European sources for Lamy and one for Lafarge, but those have dried up too. I’m not sure what happened to Lamy’s second market pricing earlier this year, but his Saint-Aubin wines online jumped about 300% in a matter of months, and the grand cru somewhere around 600%.

I was waiting for the 2017 Lafarge premier crus to be released so I could make one last grab I could almost afford. I knew Lafarge was soon to be on my never-able-to-afford-that-again list for many reasons. The first was the passing of Michel Lafarge and the anticipation of something similar to what happened to the Barolo prices with the passing of Beppe from Giuseppe Rinaldi. Then there were the oncoming challenges with the hot 2018 through 2020 vintages (which Lafarge did much better than I expected with the 2018s compared to other top growers—some of my favorites of the vintage; 2019s are already out of my range). Ultimately, the rise of Lafarge was inevitable and long overdue. I’m surprised it took much longer than many other Burgundy producers did, though as of late the style is more upfront than in the past. I secured a decent supply of the 2017 Lafarge Volnays, and a few months later the same French retailer had a restock of the same 2017 premier crus for exactly double the prices I paid. So I’m out now for good.

With all this madness surrounding wine pricing and exclusivity, and while people with more dollars than sense want to cellar and stroke their preciousss, and claim them as part of their wine museum or brag about their entitlements on their Instagram feed (can we stop that one already?), there are growers making extraordinary wines right under their noses in the same appellations that give those juggernauts a run, not only for the money but the quality too. In Chablis, that’s where our main feature of this month comes in: Domaine Jean Collet.

Before our dive into Collet, there are a few more arrivals you need to know about before what’s left of them vanish:

2022 François Crochet Sancerre (Blanc)

2022 Arribas Wine Company Saroto Branco

2022 Arribas Wine Company Saroto Rosé

2020 Château Cantelaudette, Graves de Vayres Rouge “Sans Soufre Ajouté”

2016 Château Cantelaudette, Graves de Vayres Rouge “Cuvée Prestige”

We also have the new 2021 starters in the classic range of Katharina Wechsler. Katharina got married last month and I was able to attend the wedding at the couple’s home and winery. I tasted her new releases and verified that she’s continuing her ascendency with her already spectacular wines. The 2021 Rieslings are silly good. What a year for European white wines! There will be more about everything new in next month’s newsletter, including more off-dry wines, the grand crus, and the Cloudy By Nature range. In the meantime, the following wines are back!

2021 Wechsler Riesling Trocken

2021 Wechsler Scheurebe Trocken

2021 Wechsler Riesling Trocken “Kalk” (formerly Westhofen Riesling–all from Kirchspiel)

Because Alexandre Déramé works both of his domaines alone in the cellar and with limited help in the vines, I encouraged him to use his name on the labels of his two domaines, Domaine de la Morandière and Domaine du Moulin. Extremely humble by nature, he resisted. Then he asked for advice from his family and friends and when they pushed him to do it, he caved. Progress!

I was skeptical at first when presented with the 2022 Pinot Noir Rosé but quickly realized it’s far too good for the price to ignore. I’m only sorry I didn’t know about it until this last year. Its label is not yet converted to his new design, but what counts is what’s in the bottle. All things in good time, right? The wine is simple in a perfect sort of rosé way: drink it, don’t think it. It ain’t gonna change your life, but you may hold it up to a light and say, “Damn. That’s one mighty fine Pinot Noir rosé for the price.”

The 2022 Domaine du Moulin is the first year of this wine we’ve imported. This is Alexandre’s familial domaine in Saint-Fiacre-sur-Maine, west of Mouzillon-Tillières and closer to Nantes. Its shallow topsoil is sand and silt derived from the underlying bedrock of granite and schist. It’s a lighter, fresher, and easier wine than those from Mouzillon-Tillières, home to the following two Muscadet Sèvre et Maine wines. All of Déramé’s wines are made in a combination of steel and impressive underground glass-lined concrete vats.

Also arriving is the 2022 “Le Morandiére,” from vineyards inside Mouzillon-Tillières on the eastern side of Muscadet Sèvre et Maine, across the street from Les Roche Gaudinières (L.R.G.). Similar to L.R.G, it’s on gabbro bedrock (pictured), a pale green and black intrusive igneous rock developed through the slow cooling of basaltic magma under the earth’s surface. However, the topsoil is different and composed of sand and silt with fewer loose rocks. The vineyard renders extremely solid wines, and for the price, it represents an extraordinary value with big-time chops in the context of other Muscadets. Because of the lighter topsoil, it’s ready for enjoyment much earlier than L.R.G and is aged for a shorter period and released just prior to the oncoming harvest of the next vintage.

The 2017 Les Roches Gaudinières “Vieille Vignes” comes from Déramé’s three hectares in Les Roches Gaudinières. The bedrock is gabbro but the deep topsoil is rich in clay with a lot of bedrock fragments. The vines are a mix of massale selections and old biotypes with three-quarters from 80-year-old vines and the rest fifty years old. This magnesium and iron-rich rock, the clay-rich and rocky topsoil, and the old vines with their extremely low natural yields of 25-30hl/ha at most in any year impart a dense power to its wines, obliging extensive cellar aging to reach the beginning of its decades-long drinking window. Once it’s there, it’s an extraordinarily powerful Muscadet. Alexandre ages it in glass-lined concrete tanks for three to five years followed by at least two years in bottle before release. It has tremendous aging potential, as demonstrated by the many old vintages we’ve imported (starting with the 2002 release ten years past its vintage date) and the surprising freshness it maintains after many years. Who knows what can be credited for its longevity, but there’s something special about this vineyard.

Before this summer’s sweltering heat, Romain Collet shipped me some boxes of his 2021 premier crus along with some 2019s I wanted to check in on. My first tastings of the 2021s out of vat and again just days before bottling convinced me that we finally had a true classic on our hands. Though the yield was down 30-40% on average because of spring frost, and the work especially difficult in the vineyard due to mildew during this cold season, the vigilance and remembered experience of how to manage cold years despite the last two decades of hot ones paid off. After nursing two bottles of each 2021 premier cru over a few days with each one, there is no doubt in my mind that this is my favorite young Chablis vintage in more than a decade, if not much further back.

Jean Collet’s premier crus have always been priced fairly with unexpectedly high quality, even in tough years. The only problem has been that they used average corks in the 80s, 90s and 00s, so those are a mixed bag—oxidized or epic with a few in between. Last year I had some premier crus from the 1980s over lunch with the family (and some 2010 magnums in another lunch) and they were stunning. In the last few years, their wines have crept up in price, partly due to so many losses by frost, hail, and mildew. 2017 and 2018 had decent volume but 2019, 2020, and 2021 were very short. Another reason for the slightly increased prices is that I convinced Romain that if he finished the full conversion of the domaine to organic certification to include the Chablis V.V. (nearly 100 years old) and the premier crus Montmains, Montée de Tonnerre and Mont de Milieu, no one would complain about paying a little more for the wines. (The Chablis AOC, the premier crus Vaillons, Forêts, Butteaux, and the grand crus, Valmur and Clos, have already been certified for nearly a decade.) Regardless of the increase, the wines present even more value because Romain continues to quietly raise his own quality bar above most of those in Chablis.

Collet is one of Chablis’ most consistent growers. I’m not saying that just because we import them. This is coming from a Chablis lover and drinker of nearly thirty years, and I want you, likely another fan of this appellation, to know. Throughout Collet’s forty years of working with one of the US’s most historically important French wine importers, Robert Chadderdon, they were considered one of the appellation’s top domaines. Today, the wines are even better under Romain’s direction—along with the improvement in corks! In cold years they’re classically tight and fine with more thrust than expected. In warm ones, they continue to impress and often taste like a Chablis-Côte d’Or hybrid without losing the classic Chablis mineral nuances, tension, and tighter framing. This consistency in warmer years shouldn’t surprise us given that their average vine age is well over fifty years and they’re tended to by a family with a decorated history of growing grapes since 1792. After taking the helm at twenty-one years old and still only in his thirties, Romain Collet often mentions his luck. His grandfather, Jean Collet, replanted most of the family’s vines before he retired, and their collection of 40 hectares of vineyards is enviable, especially their massive premier cru holdings in Montmains and Vaillons. When Romain is a grandpa himself, his premier cru and grand cru stable will likely average 80-90 years old. Lucky for him indeed, and for us.

Collet’s style is not that of razor-sharp Chablis, and one only needs to spend time drinking with the family to know why their wines express weight and balance somewhere between Chablis and the Côte d’Or. They drink a ton of Côte d’Or whites and reds and even more Chablis and Champagne. They’re not only Chablis-minded, they’re also Burgundy-minded on a global level.

I had the pleasure of dining with one of the wine world’s most well-educated and respected writers a few years ago. At one point, I said that I appreciate that Collet isn’t uniformly formulaic in their approach in the cellar with each vineyard. They do things differently with each site based on the location’s assets. The writer thought the contrary, that the lack of consistent cellar styling in the range—as in everything in steel, or everything in wood, or everything in whatever—is what holds them back from full recognition. I went quiet. Not because I didn’t have a follow-up argument, but because I like and admire this person and wanted to continue to enjoy our conversation. I would ask, why should a grand cru with 80cm of clay before bedrock be treated the same in the cellar as the premier cru Montmains with only rock and organic matter and no clay at all? Does it make sense that a pure rock vineyard should get the same vessel treatment as a heavy clay vineyard? I think not.

The genius and versatility after two hundred years of passed down knowledge from working in the vines, three generations of winemaking from Jean to Gilles to Romain, and their constant tasting and drinking wines from outside of Chablis, make Domaine Jean Collet stand out. They also spend a tremendous amount of time in Japan and other markets selling and eating and drinking well, which is not something every grower does. Romain continues to make wines that build on the traits and qualities of each site, rather than an inflexibility (and what some may consider a lazy approach) for the benefit of the terroirists who expect Burgundy domaines to have particular earmarks from a universal cellar style, which Collet does have but with their own unique flourishes. They break the modern Burgundian mold by vinifying some wines in steel, some in large old foudre (80hl), amphora, concrete vats and eggs, and mostly used wood. In fact, the only wine with any first-use oak is their Sécher (also spelled Séchet and Séchets). Due to all that woodiness, we haven’t imported a single bottling of Sécher since the first vintage of their wines we imported, in 2007. Sécher has become an ongoing joke between us: Will Romain eventually break me down until I import this 100% new oak wine? Sometimes it’s compelling, but there’s almost no chance. (Though at least in 2021 they put half of it in amphora.) I’m glad they put all the new oak barrels on that single cuvée instead of tainting numerous wines in the range with it—kind of a genius move if you ask me.

I’ve learned so much while tasting Collet’s wines that they’ve made me a better taster, a better importer, and a more open-minded wine lover. Diversity is one of their truest assets; it keeps things interesting, not only for us but also for them. Each of their wines has a mood, and if you know what to expect because you’ve done your research on each terroir, you can almost anticipate how Collet will work with it in the cellar and how the final wine will taste: rockier sites get big, neutral aging vessels while those with more clay age in smaller format barrels in order to “sculpt the clay,” and as mentioned, none of the wood is new with any wine except Sécher. The constant cellar tweaking guided by Romain’s supertaster talent (he won an under-25 national blind tasting competition in France at age 19) leads to the baby steps we’ve witnessed over the years as they better their range each season, come hail, frost and extreme heat.

Coming off the more opulent profiles and less acidic snap of the previous six vintages, 2021 has a more classic balance. Led with savory herbs, sweet grass, delicate pastureland floral notes, taut but sweetly aromatic yellow-green citrus, high-toned stone fruit, iodine and flint mineral nuances, this has been my favorite vintage in overall style since those of more than a decade ago.

It was a tough year, but as mentioned, the growers in Chablis didn’t forget how to manage a cold, wet, and long season. Collet started picking at the end of September and finished on the sixth of October—late compared to recent vintages. Considering how late they picked after the loss of 30-40% of their 2021 crop to frost, which would theoretically speed up the maturation of the remaining fruit once the vines come out of their shock from the hail, this should still make it a strong vintage for those in search of what’s considered a truly classic style. If Collet’s 2021s are any indicator of what’s to come, the classicists will be very happy, even though there was chaptalization on many wines across the appellation to get them up past 12% alcohol with many picked so late, conditions that lead to potential alcohol of only 10.5-11.5%. Chaptalization was always a known element with classic Burgundy wines (pretty much every year that wasn’t a scorcher) but in the last warm decades we don’t talk about it much anymore; alcohol levels are naturally high because it’s gettin’ hot.

I can’t be any more convinced about how this vintage is tailored to my personal taste. Consistent with my first cellar tastes and pre-bottling run, the first day open the 2021s exhibit a more delicate frame and are highly nuances with fine delineation, even if sometimes a little quiet—an undervalued quality these days of a freshly opened bottle that leads to an exciting journey of evolution if the proper time is granted. The acidity is present but not jarring, and the aromas are delightfully nostalgic for those who remember young Chablis from before 2000. (I can only go back to 1995 when I first discovered wine, and Chablis didn’t cross my path for about a year after that when I first went into a Scottsdale Arizona wine shop called Drinkwaters, where the owner, whom was either an Aussie or a Brit, kindly walked me over to his dusty wood bins filled with old Dauvissat, thereby sending me on my Chablis journey.) After only five minutes Collet’s 2021s begin to ascend, and they don’t stop. The problem is to try to save some for the next day to see how they extend their depth. On day two, they flesh out and become even more harmonious. Few made it to day three, but at this stage in their evolution, they seem invincible. It’s a pity that wines like these are finished so quickly when their best moments, as with any good wine, are far more than two hours after they’re opened.

As a side note, I had many bottles of Collet’s 2019s this summer. Butteaux and Valmur started out with pronounced wood notes upon first taste and prompted me to recork them and put them back in the fridge where they remained in the penalty box for a day or two. But after that, they were simply awesome, and if blinded at that time, many experienced tasters might easily place Butteaux as a grand cru and Valmur’s classification was unmissable for any taster that made it as far as Chablis. On day one, Montmains, Vaillons and Montée de Tonnerre showed very well. And on day three, all the 2019s were equally stunning. This leads me to believe that this vintage has the guts to cellar well and wade its way out of the rich weight of such a solar-powered year and rest solidly on its unusually high acidity for such a warm year.

Before the brief overview of each wine and their respective terroir elements that influence the distinction inside this group of wines, there are a few universal commonalities. They all go through natural fermentation and complete malolactic fermentation. All are lightly filtered and fined, and most, if not all, are below 13% alcohol this year. None of the wines we import are aged with first-use oak barrels in the mix, though some, like the grand crus, show nuances of newer wood notes in their first moments open because they receive mostly second and third-year wood. Those wines with rockier soils generally are aged in more neutral vessels and those with a greater clay percentage and deeper soils are aged in futs de chêne—228L French oak barrels.

We have our usual lineup of premier crus, starting with Montmains, a selection of fruit from the original Montmains lieu-dit that sits closest to the village, on the rockiest soils the Collet’s have for this designation. As one would expect from this topsoil-spare site, this is one of the most minerally wines in their range and Romain exemplifies its character with a steel élevage. 2021 is a season that pushes Montmains into even higher-toned territory and it’s more mineral than usual. Given the track record of Collet’s cellar-worthy wines, Montmains is one of their most successful. I’ve had bottles from the 1980s that have been stunning and are still at their peak. I believe this wine will age gorgeously for decades.

Part of the Montmains hill is subdivided into two more well-known lieux-dits (that can be labeled as Montmains as well, though that seems rare these days), Forêts and Butteaux. Here we find more topsoil in both sites compared to the rows closer to the village. Les Forêts’ young vines usually prove to be the most exotic of their range while Butteaux with its old vines and heavier topsoil with massive rocks in the mix is one of the stoutest, and in a blind tasting, it could easily be mistaken for a grand cru on weight and power alone. The 2021 Les Forêts was fermented and aged in cement eggs. Just before bottling was the only time it was aromatically slightly closed, but still explosive and juicy sleek on the palate. After more than a year in bottle, it’s wide open now and shows well for days—always better on day two. The 2021 Butteaux was fermented in steel, then aged in old barrels (5-10 years old). It also had a closed nose right before bottling but a big mouthfeel of plush fruit, chalky tannins, and frontloaded texture. Today, it’s full, beautiful, and ready. Like all the 2021s, I expect these two to age very well in the cellar, and I cannot recommend enough that the classicists buy as much 2021 Chablis as possible. We’ll never know when another one like this will come around again.

The long hill of Vaillons parallels Montmains just to the north, separated by Chablis village vineyards on the same Kimmeridgian marls as the premier crus but they face more toward the north—the sole reason for their village classification instead of being appointed premier cru status. Vaillons is often my “go-to” Chablis in Collet’s range of premier crus when I want a balance of everything, and 2021 is no exception. Just prior to bottling it was the most mineral-heavy in the entire range and a little tighter on the palate than the others. This is still the case with the two bottles I had over the summer. They are classically wound up and ready for a longer haul and a more patient drinker compared to Les Forêts and Butteaux. Its minerally asset is likely due to the rocky soil, and it has good body because of its 40% clay in the topsoil, which always keeps tension there no matter the vintage. The majority of the vineyard faces southeast with some parcels facing directly east, taking advantage of the morning sun with less of the baking evening summer and autumn sun. Though not as hot as the right bank with the grand crus facing more toward the west, it shows its breed with a constant evolution rising in the glass due to the many different lieux-dits parcels blended into it. I believe that Collet is the owner of the largest portion of vines on this expansive premier cru hillside, making for a sort of MVP character without anything missing due to the large stable of parcels to choose from.

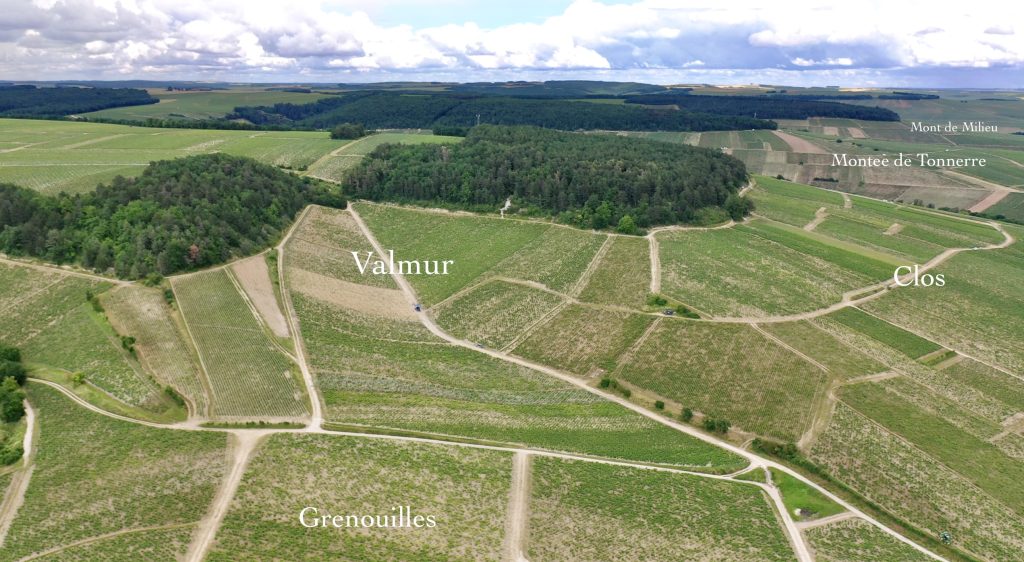

The Collets have the advantage with their fabulous collection of vineyards from both sides of the river, though most of their premier cru land is on the left bank. While the left bank wines close to the center of town could often be characterized as more mineral-dominant than those next to the village on the right bank, there are indeed exceptions. I’ve often said that Mont de Milieu is one of those wines that, though it’s on the right bank, it’s a little south of town and very left-bank in style compared to the grand crus and many of the other right-bank premier crus around the grand cru slope. There are also few who bottle Mont de Milieu. Over the years this wine has always been good but less impressive than many in Collet’s range, at least to me. These days, I lament the small quantities we are allocated (which, along with the small size of their parcels, has been locked in by our past purchases) because the most recent versions are starting to fight for top billing in the premier cru range. There is no doubt that the 2021 version of this wine is one of the best of the vintage in its youth, if not the top premier cru after bottling and more than a year afterward. We were severely shorted in 2021 on this wine and will cellar it for some years before releasing it with a batch of other aged 2021s.

There is no greater call in the Chablis premier cru world than Montée de Tonnerre. Yes, it’s like a grand cru in some ways, mostly in how regal it is, but it is its own terroir as well. Positioned between Mont de Milieu and the grand cru slope, just a ravine away from Blanchots and Les Clos, it finds the balance with a gentler slope in many parts than the grand cru hillsides which have many different aspects and greater variability between the crus. For us mineral junkies, Montée de Tonnerre thrives best in the coldest years. In hot ones, the soil saves freshness but the mineral punch gets tucked further into the wine. While it’s celebrated so highly among Chablis, and people always talk about how much they love the “minerality” of Chablis, this cru is one I find to often be least dominated by strong mineral impressions compared to many of the other premier cru sites; it’s there, but it doesn’t particularly stick out by comparison. This is likely because of its greater soil depth before bedrock contact—especially the further one goes down the hill. One can see on a vineyard map that the bottom quarter of this hill, under the lieu-dit “Chapelot,” is not a premier cru classification, which is likely due to heavier soils at the bottom rather than its exposition. The same can be said about many of the grand crus with deeper topsoils: less mineral impression dominance and more horizontal, while those with shallower topsoils are more mineral heavy and vertical. 2021 highlights this super-second’s shortcoming on mineral qualities (of course, only within the context of other Chablis premier crus), and this year it’s off the charts. My recent tasting notes from a couple of bottles I drank this summer were the same as when I tasted them in the cellar just days before bottling. The short version: perfect balance with a bigger mineral nose and palate than usual, sweet greens, passion fruit, DELICIOUS!!!

Like the grand crus, Montee de Tonnerre and Mont de Milieu are principally fermented and aged in two to three-year-old futs de chêne, with fewer older barrels in the mix.

Collet also has (in very small quantities) the grand crus, Valmur and Les Clos. Their Valmur is situated at the top of the cru on its south side, facing northwest, which was less ideal for a grand cru decades ago but perfect for today’s shifting climate. Stout and minerally, I believe it to be one of the most consistently outstanding overall wines in our entire portfolio. The 2021 remains tropical but with bright and tense fruit. Valmur is a grand cru all the way, and 2021 should be the best year since the gorgeous 2012, which we tasted four months ago and found earth-shattering! Les Clos is its equal but gilded with Chablis’ royal trim and the sun’s gold, even in the cold 2021. The topsoil toward the bottom of the hill is deeper and richer, bringing an added advantage against the hydric stress of warmer years, but disadvantaged in fending off frost–though it’s the first to be protected when Jack comes to town. The 2021 is a little backward thus far (a good thing for such a young grand cru) and has a denser core than the Valmur. Les Clos also stands out of the range in style, leaning more toward the Corton-Charlemagne power and ripeness of fruit, golden color, and richness in body.