On the night of our visit to Les Carrières de Lumières and Van Gogh’s asylum, dinner started at ten. By then I was starving and as luck would have it, it was yet another Provençal feast. There were as many oysters as I could eat, pulled from the Mediterranean, and they were delicious yet some of the saltiest I’d ever had. Also, roasted purple potatoes, parsnips, and the artichokes that I had helped prep that morning, the young stalks and hearts trimmed (no thanks to me) and sautéed to tender perfection. And that was the night I was introduced to brandade, a specialty of Provence made from salted cod blended with olive oil, mashed potatoes and milk. I took scoop after scoop and couldn’t stop myself until I felt unwell.

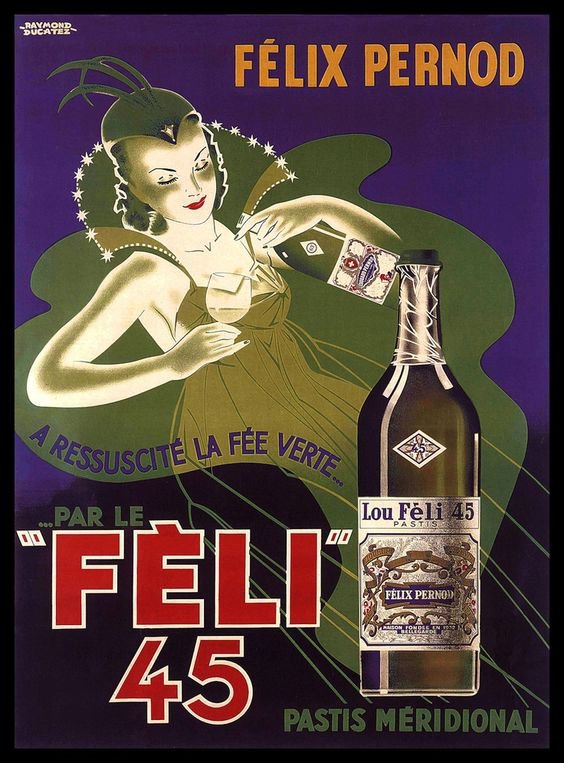

The leftovers of the salmon tart and breque from the night before taunted me enough to have just a little more, as did the tiramisu from lunch and that bottomless bowl of chocolate mousse. Thierry came out with a huge tray of cheeses and yeah, I had a little of them too, and I washed it down with some Beaujolais and a hearty Syrah from the Northern Rhône. After espressos all around, the scotch, pastis and cigarettes came back out and the cloud of smoke returned to its rightful place over the table.

The people who lived in the rental wing were having a party in a big tented-over area across their driveway; the space was perfect for the occasion as it contained a big improvised outdoor lounge, packed with old tattered couches and junk. A DJ was spinning records and some colored lights flashed in time with the thumping beat, the cigarette smoke collecting thickly there as if pumped from a fog machine. Two young women were serving crepes out of a converted camping trailer, practicing for when they were planning to bring it to music festivals, which I thought was a genius idea. The crowd was distinctly bohemian, in a modern, Burning Man sort of way.

The rapid-fire chatter of French around our table was nonstop and I continued to decipher only chunks, here and there. I repeatedly made attempts with my carefully practiced vocabulary, which my fluent sister said was perfectly serviceable, but got mostly looks of confusion. Much of the language of the trip flew over my head, not just the French, but the advanced concepts of wine attributes, vigneron techniques and vintages variations discussed over dinners and barrels that were interesting, but often just as Aramaic.

The trip so far had been—and would continue to be until the end—a sensory overload, the most intense of cram sessions, a humbling experience. Lifetimes of information were being thrown at me and my challenge was to observe from a cool-headed remove and learn what I could without labeling what I didn’t completely understand with half-baked explanations. It was an exercise in just being present and experiencing everything with all of my senses.

On Easter Sunday, this heathen slept in. It had taken me forever to drift; I was either still jet-lagged or suffering from eating so late again, or both. Downstairs, Sonya was busy at the stove with the different parts of “the baby of the goat,” as she charmingly and disturbingly called it, and the pieces were split among four different pots, with more in the oven. It was 9:30 A.M. and she had begun Easter luncheon preparations hours earlier. I remarked on her early start, and she said she prided herself on being one of the last to bed and earliest to rise.

She explained that though it was more traditional for the French to eat lamb on Easter, she preferred goat for its more elegant flavors. But it was harder to get; she had to go to her local butcher weeks beforehand where she chose the living animal from the others in the pen. I thought of all the videos I’d seen pop up on social media over the years with the cute little wide-eyed kids hopping around all spastically and adorably, and how many Americans I’ve known (mostly vegetarians) who have wanted them as pets. That morning, Sonya had gone to the village of Eyragues, closer to the Alpilles mountains, to pick up that very same kid after it had been divided into a pile of brown paper packages, tied up with string.

She was nice enough to clear a stovetop burner so I could make my eggs, which I quickly inhaled with more baguettes and Nespressos. The morning was another idyllic one of sitting around in the sun dappled yard, minus the food prep. After two days of festivities, people were starting to slow down a bit. There were pre-lunch cocktails poured all around and still the frustrated shake of a dying disposable lighter to get it to light one more cigarette, but things seemed to be moving in slow motion. Many of the others had stayed up even later the night before than the previous one, and it showed.

I was perfectly fine with lazing about for a while, and I wandered around the house taking pictures of a rusting and abandoned patio set around one corner; a big stack of neatly chopped firewood for one of the many fireplaces around another; a small shed overcome by ivy, rotting and collapsing under its own weight; the cozy mismatch of upholstered chairs in a small salon with sketches of Arabic men in keffiyehs and Persian tapestries on the walls beside a fireplace mantle where four Buddhas sat in a row; a cluster of eau de vie bottles in a tall cabinet, their labels browned and curling as if they’d been abandoned for years; a tray of nine jams and preserves that Pierre had made, arranged neatly on an intricately carved sideboard beside a yellow plastic fly swatter.

There was a commotion outside and I joined everyone as they clambered to bring the pieces of the big table over to a patio that provided a modicum of shelter from a sudden cold wind. The branches above waved back and forth like they were suddenly excited. It was “Le Mistral,” Pierre said, as he directed traffic, the cold wind that kicks up and comes from the north and only blows for one to three days. “Or six or nine!,” I heard someone chime in. All these odd numbers made it sound like magic or myth, so I later verified via Google, and Pierre’s one to three seems to be the official consensus.

As we settled at the table in the new location, Sonya came out with big steam trays of goat and roasted potatoes. Pierre ceremoniously carved chunks from the legs and ribs until the trays were full of pieces ready to be served. Everyone handed over their plate and he dished out small portions. Mine was a fatty piece that I’m afraid I picked at a little priggishly; again, I’m really not much of a meat eater, but I made a sporting go of it. We had more of the delicious white asparagus and ample portions of baguette to go with it, so I got my fill.

We were joined by two late arrivals, Veronique, and her fourteen-year-old daughter, Ynez. Veronique is a teacher and an old friend of Sonya’s, and she was drinking and smoking as quickly as she could in what seemed like an effort catch up with the rest of the party. Ynez and Roman’s ten-year-old daughter, Leiah, played Patty Cakes and guessed at finger drawings on each other’s backs as the meal wrapped up. When someone asked about where Sonya had gotten the goat, the fourteen-year-old looked up, alarmed. She had recently converted to vegetarianism and hadn’t really been paying attention to what she was eating; she clearly needed more practice. The revelation of the “baby of the goat” sent her into a state of wide-eyed shock that had everyone else poking fun and laughing.

Ted wanted to get in some more sightseeing before leaving Provence the next day, so we set off and made it to St. Remy by early afternoon. It being Easter, the place was pretty packed, and as we circled for a while looking for a spot, we got an impromptu tour of the area around the beautiful town center. The charming old buildings and tree-lined streets got Ted fantasizing about moving there with Andrea. He said he could easily see setting up shop in a cozy flat, and it couldn’t be that expensive, could it? Andrea nodded and smiled agreeably; she was used to humoring his flights of fancy, and I would hear him say the exact same thing about a couple other villages in the coming days.

Andrea was on a mission to buy some new shoes, so once we walked into town, we split up. Ted and I set off with no destination in mind and wandered the maze of narrow, cobblestoned alleys, many with stone archways above us that joined the buildings, all constructed of rough gray blocks that made it feel like we were walking around in a giant castle. But St. Remy is an ancient village that’s also filled with incongruent modern commerce, mostly sleek boutiques and wine shops in spaces that I imagined were once reserved for butchers, boulangeries and blacksmiths.

The conversation in the car about relocating his domicile sparked a train of thought that has incessantly preoccupied Ted in recent years: while he now finds himself with a small level of success much earlier than he ever expected, and he is consistently grateful and humbled by it, he is at the same time feeling the pressure one does when they begin to reach a pinnacle, to do what they need to do to stay relevant. “It seems that after you meet the greatest of challenges, you should be able to sit back and enjoy it,” he said, “but this is not the case as a wine importer. There is no time to rest—there is just too much to do.”

It took us a while, but we tracked down a chocolate shop that Ted had been meaning to check out for a while. Joel Dürand is a famous chocolatier known for the finest selections with unusual flavors. Each little square has a gold letter printed on top that signifies interesting ingredients such as black chocolate with star anise flower, black chocolate with cloves and lemon zest and dark chocolate with Corsican arbitus honey, which I sampled with much pleasure. Ted put together a box for Sonya as a thank you and was sure she would really like the milk chocolate (which she prefers over dark chocolate) with lavender flowers from Provence.

We retraced our steps and found Andrea in a little boutique wearing some gold, high-heeled sneakers. They were apparently more comfortable and practical than they looked, and she said she would wear them every day, including in the dirt of vineyard tours. I applauded her mix of fashion with pragmatism. Ted told her she certainly deserved them for putting up with him, and gave her a big hug and kiss.

Dinner at La Fabrique was quieter than the previous nights, what with the holiday weekend coming to an end, consumption fatigue taking its toll and the looming dread of a return to work. Sonya said the menu for the night consisted of “cheese, lettuce and cake.” I thought she was kidding until she brought out the three cakes she had baked that day: chestnut, chocolate, and pineapple upside down and bowls of mixed greens and vegetables. It was a paradoxical meal of salad and dessert. “A light dinner,” she called it.

I dove in and also foraged for some leftover brandade in the fridge as the mistral whistled in the eaves above. Pierre drank his rosé and smoked in silence. The huge selection on the cheese tray Thierry brought was finally dwindling, and some of the favorite goat cheese pyramids disappeared as they were being featured as the a main course, and were quickly followed by the wheels of triple crème, Compté and countless others I didn’t know.

As we ate, Sonya talked about a friend of hers who had moved to the Swiss Alps and married a renowned Gruyére maker. The cows there live on sparse and straggly grass, and the high altitude diet and raising techniques result in some of the best cheese in the world. It seems that in dairy, as with wine, the product is greatly strengthened and improved by the struggle to extract the densest, most evasive nutrients from a stubborn soil. I took it as a lesson in fortitude that we could all learn from, for anything we do.