Arnaud Lambert

This website contains no AI-generated text or images.

All writing and photography are original works by Ted Vance.

Short Summary

Arnaud Lambert established his eponymous domaine in 2017 with the merger of his family’s Domaine de Saint-Just and the rented parcels from Château de Brézé. He farms more than 40 hectares of organic vineyards in Saumur’s continental climate with unusually dry conditions due to the rain shadow effect of the Massif Armoricain. In this part of the “Anjou Blanc,” the vineyards are on tuffeau limestone bedrock with topsoil variations of clay and sand. Still wines from Chenin Blanc and Cabernet Franc are vinified and aged in variations of steel, concrete, and small and large wooden vats without added sulfites until bottling.Full Length Story

The rise of Arnaud Lambert is no surprise. Since our first meeting in 2010 at his home in Saint-Cyr-en-Bourg, a dozen or more kilometers south of the Loire River, this unknown vigneron’s potential was obvious—not only with what skills he already possessed, but how clear it was that he would sharpen them and grow into the spectacular talent he has become. Every vintage seems to eclipse the previous, and with some of the most gifted Cabernet Franc and Chenin Blanc vineyards in the Loire Valley, he’s only getting started.

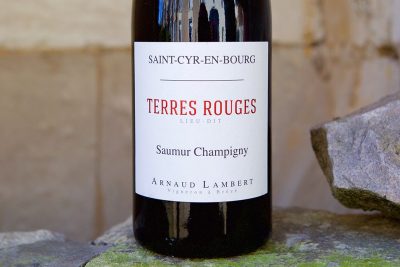

What’s most incredible about Arnaud is his ability to churn out such quality with nearly twenty different cuvées rendered from more than forty hectares of vineyards; although this is a lot, all of his wines seem like they’ve come from a domaine with no more than five hectares. His wines are spectacularly etched jewels, short on pretension and confection, and long on harmonious depth and purity. Everything from his entry-level reds (Les Terres Rouge and Clos Mazurique) and whites (Les Perrieres and Clos de Midi) is astounding, and the upper class of the range developed for more time in the cellar are striking and warrant exploration for any serious Loire Valley wine enthusiast.

Domaine Arnaud Lambert, a relatively new name, was established through the merger of two labels in 2017: Domaine de Saint-Just, his family domaine within the Saumur-Champigny appellation, started by his father Yves Lambert in 1996, and Château de Brézé, a historic Saumur estate whose enviable collection of vineyards for which the Lamberts signed a twenty-five year contract starting with the 2009 vintage. This is why some wines are labeled differently within some vintages (mostly between 2015 and 2017); for example, in 2015 there is a Clos David labeled under Château de Brézé as well as Arnaud Lambert—so long as they are the same vintage date, they are the same exact wine.

As mentioned, in 2009, a fortunate opportunity in the form of twenty hectares from the historic Château de Brézé vineyards, all of which are individual clos (walled in single climat vineyards), arrived at the doorstep of Yves and Arnaud. At the time, the quietly legendary history of Brézé was only a whisper and its storied glory nearly lost. This stroke of luck would forever change the Lambert family’s fortune and their place in the world of wine. The restoration of one of France’s greatest forgotten treasures would come full circle. (Read another article I wrote some years ago about Brézé, The Greatest Forgotten Hill.)

An Unexpectedly Early Change of Guard

It’s not easy for anyone to witness someone cut down in their prime, especially one’s father. In 2011, Yves Lambert succumbed to a relatively quick and forceful cancer decades earlier than what would’ve been expected from a perfectly healthy and energized man in his 60s. Although I missed my opportunity to meet Yves, it’s easy to imagine what kind of man he was if you know his son.

I’ve had the fortune to taste several wines crafted by Yves, starting with the 1996 vintage, when Domaine de Saint-Just first began. Some of them are startlingly good and remain seemingly bulletproof, like many Cabernet Franc wines grown throughout this area of the Loire Valley. (Is there a better, more age-worthy bargain in wine than Cabernet Franc from this part of the world? So many examples of ancient and fully intact wines pop up here and there, and still at usually affordable prices.) In Yves’ last years he began to gravitate toward a more natural approach in the vineyards and slowly they began to mentally prepare to adapt their entire philosophy to it, which not only includes a way of growing wine, but also a way of living. While Yves wasn’t able to see through the entire conversion of everything and bear witness to what Arnaud has already accomplished in less than a decade after his passing, he was the spark that lit Arnaud’s fire.

Great wine begins in the vineyard. This is an exhausted cliché, but there is no truer statement in growing fine wine; the taste of wine from grapes conventionally grown compared to those more naturally grown by whatever earth-connected philosophy is employed—organic, biodynamic or other natural methods—is stark. Not only can you taste these connected vineyard practices (whether good or bad), you can see it in the health of the vines and feel the energy while standing among them.

I don’t intend to espouse some kind of grape-growing sorcery or mysticism, but the obvious physicality of a thriving nature beyond rock, soil and the vine is evident in the form of the macro and micro fauna and flora, the richness and softness of the soils and the herbs and grasses that emit aromas as you walk on them. Finished wines originating from living vineyards—the collective organism that enriches the vine and its grapes—are endowed with subtleties that give rise to the confluence of a wine’s vibration and structurally defining factors of terroir and the abundant characteristics uniquely imposed by its maker. More naturally grown wines are more intricate in ways often apparent to seasoned wine experts, but certainly not limited to them. Within wines deeply connected to nature there’s real matière (a French word that implies substance), not an empty frame.

Arnaud’s 2010 vintages were good, but amplified in a more attention-grabbing way and less refined than today. His communion with nature has led him to seek over all things honesty in his wines, free of makeup and unnecessary weight and extraction that could blur the fine lines true to his terroirs.

Between 2010 and 2012 he reined in his Cabernet Franc wines, going from full extraction during the vinification with three pumpovers or punchdowns per day to perhaps three in the entirety of the vinification on all of his reds, from the basic Clos Mazurique aged in stainless steel, to his top flight wines Clos Moleton and Clos de l’Etoile, both aged for thirty months in French oak barrels before bottling. With the Chenin Blanc, despite the obvious win they’ve been since 2012, he set the course to release them from their naturally aggressive tendencies—deafening high tones and scathing acidity—and transform them from raw, unbridled power to refinement and focus while maintaining a vigorous but contained electrical current.

Arnaud, like many of the wine world’s luminaries-in-the-making, has adopted the philosophical approach to allow the terroir to define the wines, rather than the other way around. He’s most known for his wines grown on Brézé and no more than two kilometers away, Saint-Cyr. These two hills gave inspiration for the subtle, two-line, soft hill shaped logo on his labels. Within his range, certain wines are vinified and aged the same in the cellar from both hills, to create a comparison of their terroirs. There are three whites and three reds from each hill that have a sister wine from across the way. For example: the mid-level red wines are Clos Tue-Loup, from Brézé, and Montée des Roches, from Saint-Cyr, which are vinified and aged the same to demonstrate their differences. (There is more on this in the Lay of the Land text further below.)

An important practice that Arnaud likes to bring attention to is his approach to sulfites. He prefers that all wines he vinifies and ages to be sulfite free during their processes until bottling. In his opinion (one that I share), it offers the wines the opportunity to further build on characteristics influenced by the season and the nature he works to preserve and protect in his vineyards. These more delicate elements may be greatly affected by sulfites, with many of them entirely killed, except the strongest. It seems that sulfites reserved for later in the aging process also allows the fruit characteristics to open up further without expense to the seriousness of the wine. This may shed some light as to why many natural wines (when they don’t emit foul odors) are often abundant and unapologetically fruity—in the best sort of way, of course.

If sulfites are not carefully approached with wines grown from Brézé and Saint-Cyr, they can be unforgivingly potent and raucously acidic. Their razor-sharp edges need softening, and the administration of sulfur after the wine has had some time to sort itself out in the cellar is more often than not a wise approach. Early sulfite additions may (in theory) clip some of the wine’s potential authenticity, especially with subtle characteristics. It’s often my experience that early sulfited wines may be harder and squarer than those sulfited later. Also, wines aged in a properly run cellar—healthy and balanced grapes, temperature regulation and appropriate hygiene—without sulfites early on tend to build a sort of inexplicably higher resistance to oxidation, therefore it often requires less total sulfur to achieve the amount of desired free sulfur; hence, a wine with potentially more personality. Wines with more intervals of sulfite additions throughout the cellar aging process tend to need more sulfites (like an addict needs a drug) and by the end are typically far greater in total sulfur. They may also exhibit more dried out fruit characteristics and a potentially coarser tannin sensation due to the stripping nature of sulfites.

While sulfites are a useful preservative and antibacterial treatment, they also take away good qualities from a wine. The amount of sulfur needed to protect a wine is also based on its pH level. In this part of the world, the pH levels are extremely low, which renders them far safer with lower sulfite doses.

During the aging process, Arnaud works with many different types of vessels, large and small, and approaches Cabernet Franc and Chenin Blanc nearly the same, just as one would see in a Burgundian cellar with Chardonnay and Pinot Noir. Arnaud was educated in Beaune for his enology and viticultural studies and his mid-and high-end wines show it in their somewhat Burgundian-like shape and aristocratic polish. The entry-level wines are meant for early consumption and are typically raised in stainless steel for a six-to-eight-month period and shortly thereafter sent to market. The mid-range wines all go into French oak barrels, with a mix of new and old for usually a year or so. The top in both red and white are aged more extensively in French oak, with the best white crus taking some time in large foudre as well as small French oak barrels. This is Arnaud’s approach du jour (circa 2019/2020), but he’s always on the move and will surely continue to learn more and adapt as the years go by.

Arnaud Lambert’s domaine vineyards are located in three communes within the Loire Valley’s Saumur region, a subsection of the larger Anjou area. This is the land of Chenin Blanc, Cabernet Franc and inexpensive bubbles (an underutilized talent in the area). He principally works within three communes: two within the Saumur-Champigny appellation (Montsoreau and Saint-Cyr, on opposite sides of the appellation—north and south, respectively) and the resurrected commune, Brézé, included in the broad AOP Saumur, on the southernmost border of the AOP Saumur-Champigny.

Saumur and neighboring Anjou have a lot in common, but can be vastly different with the end result, at least within the context of the same grapes. I will attempt to shed some light on them to help set the stage for a more in-depth study within these areas and their specific wines.

First, let’s start with the similarities. Both Anjou and Saumur are relatively low precipitation viticultural areas due to the rain shadow caused by the Massif Amorican, an ancient mountain range thought to once be as high, or higher, than Central Europe’s Alps, now reduced to mere hills after hundreds of millions of years of erosion; its tallest “mountain,” Avaloir, sits at a mere 1368 feet. This rain shadow shakes water loose from the clouds as they move toward the east. This is what makes organic and biodynamic farming within the nearby white wine producing appellations of Muscadet, toward the west, particularly challenging by comparison. The weather in Saumur and Anjou is more continental with warm days, cold nights and the influence from unrestricted cold northern winds. Most notably, both Anjou and Saumur are particularly focused on Cabernet Franc and Chenin Blanc production.

There’s much more to cover with regard to the differences. First, we could say that despite both being short on rain, Anjou has more humidity, which makes it ideal for the noble rot sweet wines. Saumur is drier, and perhaps even cooler with the proximity of most of the vineyards less impacted by the Loire River and its tributaries, unlike appellations like Savenièrres and its neighboring AOPs La Coulée de Serrant and La Roches Aux Moines, and the Coteaux du Layon, which picks up a lot of humidity from the small Layon river (more like a creek) when it floods the surrounding flatlands. In Saumur, the Loire River can be right next to vineyards, or as far away as 15-20 minutes by car toward the south. Anjou is one of the greatest spots in the world for serious sweet wines; Saumur less so, despite the noted history of Château de Brézé exchanging wines centuries ago with the world’s most famous and long-lived dessert wine, Château d’Yquem, in the Sauternes region of Bordeaux—I suspect it was an exchange of sweeter wines more so than still.

Geologically, they are vastly different, in fact, nearly opposites. The Anjou gets its geological heritage from the Massif Amorican, an ancient relic from Pangaea, the last supercontinent when all the continents we know today were connected, or at least closer together. They refer to this area as the Anjou Noir, for the color of its darker bedrock. Saumur is in the Anjou Blanc, so-called because of the color of its bright, grayish white limestone rock. Anjou is largely composed of a mixture of metamorphic rocks, like gneiss and crystalline schist, as well as igneous rocks, with much of the topsoil being derived from the decomposition of the bedrock. Like Saumur, there are sections largely influenced by river alluvium, but they remain mostly acidic soils. Saumur’s famous tuffeau limestone bedrock is a light and porous rock composed of about 20% sand and the remainder calcium carbonate. If you’ve got eyes of an eagle you may be able to barely make out that there are tiny flecks of quartz and black mica mixed in with this limestone, giving it a slightly grayish cast; I recommend looking at it under a magnifying glass, or the geologist’s magnifying field tool, the loupe—no microscope needed.

These dark components found in the local tuffeau originate from the erosion the Massif Amorican located west of Saumur. Saumur’s bedrock depositions come from the Cretaceous era from some 65-140 million years ago, and are part of the Paris Basin, a geological series of marine sedimentations deposited over a one-hundred million year stretch. The tuffeau in Saumur comes from either marine or lacustrine sediments (from lakes) and is highly alkaline, a drastic contrast to those typically found in Anjou. There are also some are pale, soft mustard yellow-colored tuffeau, which takes this hue from more iron in the rock.

Now that we’ve established the bedrock, in comes the complicated part: the topsoil. Topsoil composition and depth, and the microclimates (many of which are dictated by the proximity to the Loire River) of Saumur and Saumur-Champigny define its communes and their wines. You can count on tuffeau underneath just about any vineyard, but the depth can vary and so can the sedimentary layers above it. There is also a notable amount of yellow, red and orange silex (chert, or flintstone) visibly scattered throughout vineyards in the area of Saint-Cyr and Bréze. They are particularly hard and somewhat rounded (at least for a stone as hard as these are), indicating the extensive amount of travel much of the topsoil in the area has made.

Montsoreau, Saint-Cyr and Brézé

In Montsoreau much of the vineyards for Cabernet Franc are planted up on a plateau that sits above the Loire River on flat sites with deeper clay composition, between sixty centimeters to a couple meters deep. (It should be noted that Cabernet Franc is typically a higher performer when planted in deeper, clay soils.) There is also a special, nearly pure tuffeau limestone site within Arnaud’s Montsoreau vineyards with almost no topsoil from which he makes a superb Chenin Blanc simply label, Montsoreau.

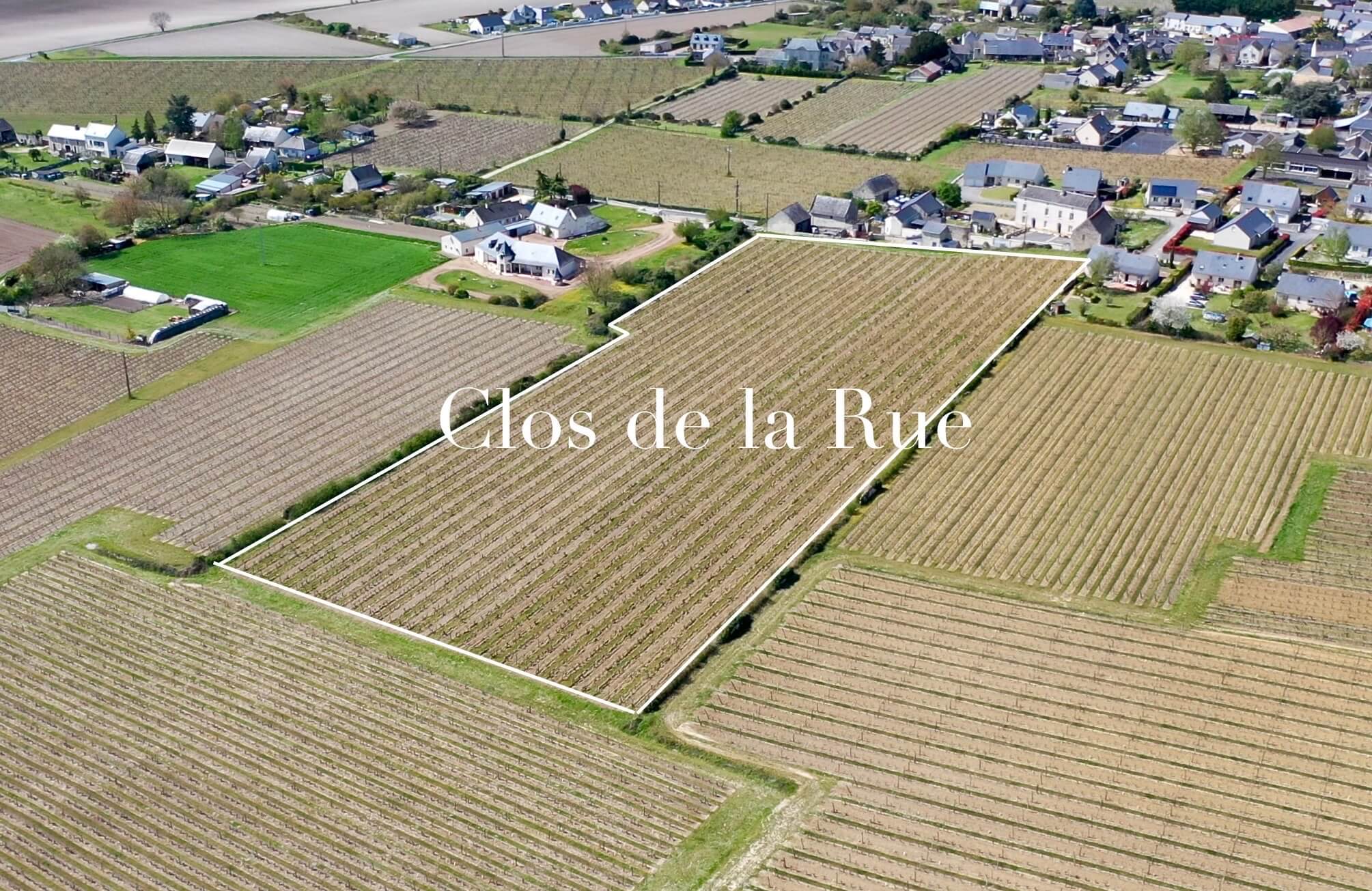

In Brézé, the topsoil is all over the place and varies greatly within sections of the same clos. For example, Arnaud’s Cabernet Franc vineyard, Clos de l’Etoile, has a topsoil of heavy clay in the upper section and is more loamy (a mix of clay and sand) at the bottom, with a transition of only about ten to twenty meters; Clos de Midi, his largest clos, has a heavier clay section and another more sandy section. Clos David, one of his top whites, is all on sand topsoil atop tuffeau and the other, Clos de la Rue, is a shallow layer cake of sand and clay with tuffeau bedrock below. There’s a forest on top of the Brézé hill that surely impacts the microclimates of each vineyard next to it, as demonstrated by a series of microclimate maps provided to me by Arnaud. Brézé is historically a white wine hill and the reds can feel more like a white with red nuances and tannin.

Saint-Cyr by contrast to Brézé is much more geologically homogenous. Heavy clay sits atop almost all its vineyards, making for red wines with more weight, power and tannin, and whites with more earthiness and dense power, while maintaining strong mineral impressions. Unlike Brézé, there is no forest (or hardly a tree) on the hilltop of Saint-Cyr, but like Brézé there are many aspects and exposures to choose from. Arnaud’s Chenin Blanc sites on Brézé have a larger mixture of sand and clay elements, making for wine with more high tones and a strong lead of more polished mineral characteristics.

Keep in mind that these are but a few references and there is an individual story to tell about each lieu-dit (or named site/vineyard) on any label within either appellation, Saumur or Saumur-Champigny. There are other places within the large flood zones and flat areas of Saumur, like Romain Guiberteau’s Cabernet Franc vineyard, Les Motelles, with root systems that likely have no contact with the limestone bedrock deep below, only a mix of alluvium that goes several meters down.

Beyond each commune’s general overview, it’s hard to generalize anything, but there are some observable consistencies between the Anjou Noir and Anjou Blanc and the way the wines taste. Everything is a consideration, but one of the most notable is how the soil and bedrock marks the wines.

Saumur Chenin Blanc is often a very straight wine with pronounced acidity. It’s a great spot for sparkling wines, so you can imagine the freshness of the still wines. Many of the Chenin Blanc from Anjou seem more diverse in characteristics and this may be due to its great variation between proximity to more humid areas closer to water and the diversity of rock formations. They are often more salty, and more like coarse salt than the ocean spray-like salinity of the whites of Saumur. I also find unique characteristics of Anjou whites that may remind one of wet forest elements and more savory fruit, floral and herbal qualities. Saumur, including whites from Brézé, is more direct and less variable in nuances: heavily mineral (if in contact with tuffeau bedrock) and citrus, with a compact core. The depth of topsoil really counts with Chenin and defines the shape of each wine: clay topsoil imparts density, while sandier soils bring more ethereal qualities. However, there is some kind of magic in the unique wines of Brézé that’s hard to describe, like some sort of intoxicating and almost sweet-smelling fairy dust.

I have less experience with a multitude of Cabernet Franc wines from Anjou, but what I’ve had seems to demonstrate more of a woodsy quality (and not just the abundance of pyrazines in this grape variety, like green pepper and/or forest notes), with animal, iron and metal textures, wild fruits and earthiness than those from Saumur and Saumur-Champigny—perhaps it could be said that they are more rustic in general. Those from the Anjou Blanc, seem more regal and polished—perhaps even slightly predictable in this way. I have yet to dig into the different variations of clay formations within Saumur-Champigny, but the wines are usually a bit more straight, and reliant on contact with the bedrock to bring something interesting. Vine roots not in contact with tuffeau bedrock, like those on deep clay beds, or alluvial depositions, are still delicious, but a little more left-bank Bordeaux-like than Burgundian; they tend to exemplify their varietal characteristics more than a strong mark of the terroir, except that they are perhaps more universal, middle of the road wines without extreme high tones or low tones—similar to Bourgogne Pinot Noir wines on the lowest slopes in Burgundy with deep clay soils, or Crozes-Hermitage from the Chassis plain composed of river alluvium compared to the Crozes-Hermitage granite bedrock communes of Gervans or Érôme, behind Hermitage.

The site is important and that is what should be focused on, especially in places like Brézé where things can change within a couple of meters, altering the shape and expression of wines made from neighboring parcels.

Arnaud Lambert - Cremant de Loire, Rosé

Out of stock