Last month I finished a new Audible favorite, easily in my top three best experiences of all time on this app, though it should be noted that I only began my subscription last year. The Book Thief just tied A Gentleman in Moscow, and as soon as I finished it I got it on Kindle too and read it cover to cover in short order (of course after relistening to the last chapter three or four times; in addition to rewinding to many more chapters that had nuggets I might’ve missed). Another is Surrender, narrated by the author, Bono, which is full of bedtime stories told by what sounds like a leprechaun drinking beer in a Dublin pub, his voice scratchy, and almost completely worn out. It includes tales from before the start of U2 and follows a lifetime of incredible stories that would defy belief if they were about a rock band of any other caliber. From doggedly getting themselves signed by a record company (after delivering their demos by bicycle) to meetings in the Oval Office, reluctantly suckered into a charity concert by Pavarotti, and with every accent attempted by Bono himself, all woven into the story of a young man and his brother and father who never got over the unexpected early passing of his beloved mother, Iris. (Do any of us ever get over our mother’s passing?) Aside from the obvious advantage Bono has with his one-in-a-billion talent for entertainment, the narrator of the audio version of The Book Thief, the lively actor, Allan Corduner, was second to none. Or maybe he tied Bono.

There are few audible books I recommend more than The Book Thief. I didn’t know they released a film adaptation in 2013 starring Geoffrey Rush until I was halfway through it and beaming with enthusiasm to share it with my wife. Andrea is a voracious reader and a sucker for romantic war stories and historical fiction. As a Portuguese language student, she decided to read the bible-sized Portuguese novel, Diz-Me Quem Sou, with its 1,104 pages, in small print. She lugged this five-pound tome everywhere for almost a year and her eyes are getting rapidly worse, as are mine. I finally bought my first reading glasses at the end of June, but not until I completely wore out the frame of one of her two pairs over the last year.

Since it was published in 2005, I thought it possible she had already read it, but when I asked her she said, “No, but I watched the movie,” popping my balloon and then moving on to some pressing detail about the renovation of our endless Portuguese countryside rebuild that will likely be ready for us just before we die. “You must listen to this book on Audible!” I insisted, and she still seemed uninterested… “But mi amor, there is no way that movie can possibly stand up to the actual words of such a great book, and the narration is the best. You’ve listened to Bono and Prince Harry, you have to listen to this one!” One day she will thank me for pushing her so hard.

If Allan Corduner narrated a thousand books, I’d listen to them all. He told with great impact Markus Zusack’s story about the intense grief, stress, and brutality of war, and balanced it all with moments of much-needed hilarity when the main character, Liesel, is out of the direct line of fire. His comedic handle on the sometimes sharp and jolting quality of exaggerated German accents often gave me a solid ab workout between free-weight sets while I was surrounded by a bunch of solemn Spanish and Catalan bodybuilders who shot confused looks at the American guy who was giggling and sometimes wiping away tears of laughter as I lifted. But I hit pause out of caution during heavy sets for fear that Allan might pierce my focus underneath too much weight, as it did while I was benching (almost dropping it on my chest) as Pfiffikus was introduced: “Geh‘ scheiße!”

Speaking of Spain, we finally have a new boatload arriving from the peninsula with a lot of goodies, only maybe too many all at once. We will stagger their release, but you can expect to soon be tempted by Prádio and Augalevada’s long-awaited new releases, Portugal’s Arribas Wine Company and a Mateus Nicolão de Almeida restock, and more surprises that will be covered in September. But first, we will begin with perhaps our biggest Spanish superstar, and then we’ll follow that with one of the Loire Valley’s greatest talents.

I know of very few European winegrowers outside of Ernst Loosen who taste as much European wine outside of their home country as Manuel Moldes, though Ernie’s access to epic wines with age seems unparalleled. I rarely mention a wine to him that he doesn’t already know. And the ones he doesn’t know, are often unknown outside of the village in which they’re made.

After more than a dozen years making wine, Manuel is no longer only tinkering with ideas, he’s mastering his craft, especially with Albariño. In my book, he has matched the likes of growers like Arnaud Lambert and Peter Veyder-Malberg, the latter of whom I sent some of Manuel’s bottles, and he’s a big fan now too, as is Arnaud after meeting him in Saumur some summers ago while on tour with me. We are lucky to have such talents in our collection of US growers and even luckier to have Manuel as a close friend—the same with Peter and Arnaud! On my last visit with him two months ago at his brother’s restaurant, Tinta Negra, I left frustrated by my level of Spanish comprehension. I’ve studied at least four days a week for more than two years now, but I totally bombed. Even if he is one of the most difficult to follow out of all those with whom I speak Spanish, it seemed like my mind was out to lunch. However, I understood him perfectly well when he smiled and turned to Andrea and said in Spanish, “What happened? He lost his Spanish…” I was relieved when my wife told me on the drive home that Manuel speaks Galego half the time and she too has a hard time understanding him sometimes. And she’s a native Spanish speaker!

We’re going to kick off Moldes’ lineup Burgundy style with reds first and then dig into the whites.

2021 was the season across Europe for continental/Mediterranean climate zones that have been missing the tension in their wines over the last decade; it was mostly cold all summer—perfect for fresher fruit qualities, low pH levels, and vibrant acidity. Rieslings across all countries are at their best, with impeccable balance. Burgundy and Chablis delivered wines from what seems like a long-gone era, though many had to chaptalize (at least in Chablis)—historically a very common adjustment for vintages with less sugar. (No one wants to talk about that kind of thing anymore, but let’s be honest about it, eh?) The Loire Valley hasn’t seen such a perfect Chenin year (at least qualitatively) for a long time. 2021 is a vintage I’m definitely going to stock up on. Even if Côte d’Or prices are almost entirely outside of my budget now, there is a wealth of great wines out there outside of Burgundy to drink early and to cellar long too.

It was a perfect season for the 2021 Bierzo “Lentura.” This far western area of Castille y León is a geological transition zone at the foothills of the Galician Massif and the expansive high desert of northern Spain. Geologically it is both, though perhaps a little more associated with the Galician Massif from its mostly slate-derived soils in rock and powder form: slate rock up on the steep hills, and a lot of slate-derived clay, silt, and sand pulverized by quartzite cobbles on the valley floor below. Here, summer daytime temperatures can reach 40°C (104°F) on any given day while the nights can drop by a full 20°C (35°F). The oceanic influence is blocked from Bierzo by the Galician mountains toward the west and the Cantabrians toward the north, making it much drier compared to the neighboring Galician appellations like Monterrei, Valdeorras, and the eastern portion of Ribeira Sacra. Winters are freezing and go as low as -10°C, but with little snow because it’s not such a particularly precipitous area. It’s perfect for viticulture, but the wines can often be very strong, and may similarly be described the way Hemingway wrote about Corsican reds in A Moveable Feast, “you could dilute it by half with water and still receive its message.” Surely he meant those Corsican reds with the likes of Nielluciu rather than Sciaccarellu, or however it is you want to spell those two grapes.

“Lentura” is much fresher tasting than the fuller vintage wines that came before. It’s composed of 60% Garnacha Tintorera/Alicante Bouschet, a grape not related to Garnacha/Grenache, and, sadly, only occupies 2% of Bierzo’s surface area. I’ve come to like this variety a lot for its high acidity and tannin, inky color, and virile nature. We’re in an age of elegance (which I love) but with that pendulum having swung so hard in the direction of gentle wine, perhaps one day it will swing back to favor grapes like Garnacha Tintorera, which gives varieties like Syrah a run for the money on wildness and surely on bigger natural acidity. It’s a great balance for the remaining 40% Mencía in the blend, which is naturally more suave but with far less acidity. If I’m being honest, I’ve had just a few experiences with Bierzo wines that got me excited about the appellation, but if more were made with a predominance of Garnacha Tintorera like Manuel’s, that would probably change. But since it covers only 2% of the surface area of vines, it ain’t enough for a full-scale revolution.

The first vineyard is in Valtuille at the bottom of the valley on fully exposed gentle hills at around 500 meters on red clay and quartzite cobbles. The other is from the famous Corullón, one of the most impressive wine hills in all of Europe. This legendary local vineyard faces east at 750m, applying a g-force weight to your face as you try to balance and look up at what tops out near 1000m, quickly. One needs to be mountain goat-surefooted with every move in all directions—up, down, sideways—with its precariously slippery, paper-like slate shards and greasy clay that keeps the rock stuck to the hill. With an average vine age of over seventy years and the extremity of the terroir and Manuel’s mind hard at work in these organically certified vines, the value here for such a wine is tough to top.

The 2020 Acios Mouros is different in structural style than Lentura and benefits greatly from its extra aging before release. 2020 is another great year for Rías Baixas red and white wines, which is not always the case because the reds benefit from a warmer season to soften the piercing high-tone vibration. A masterfully blended, harmonious ensemble of red grapes with distinctive personalities, it leads with the highly acidic and gorgeously aromatic and softly balsamic red Caiño Redondo (70%) and the other 30% split between the tannic, acidic, ink-black beast, Loureiro Tinto, and the suave, rustic, floral and lightly reddish-orange colored Espadeiro. Grown on granite and schist bedrock within view of the Atlantic, their naturally intense varietal characteristics are amplified by their spare metal and mineral-heavy soils and the natural saltiness that seems to be imposed by this oceanic climate. While Lentura is more generous with a little chalkier tannin chub that softens its structure and minerally body, Acios Mouros can be tough love at first taste for those not calibrated to this red wine of the highest tones. Neil Young-level feedback upon opening, it evolves into a long, hypnotic Gilmour finish. I love Acios Mouros, but my wife has to gear up and strap in to prepare for its first strike. She wants to relax and sit back at the end of her day, but this wine makes everyone sit up straight and pay attention. These 45-55-year-old vineyards sit between 20-80m altitude and are purely Atlantic in climate—two more notable differences from the continental climate and high altitude of Lentura in Bierzo.

It’s no secret that Manuel’s big ticket is his Albariño range. He’s simply reached a new level for this grape variety and few from the area match his wines’ value, and almost no one can touch them on intellect and craft. (They’re also dangerously easy to gulp down.) I believe the quality of his work must now be counted among those of the world’s great, rarified-genius white wine producers, luminaries like Olivier Lamy, Peter Veyder-Malberg, and Klaus-Peter Keller, to name just a few.

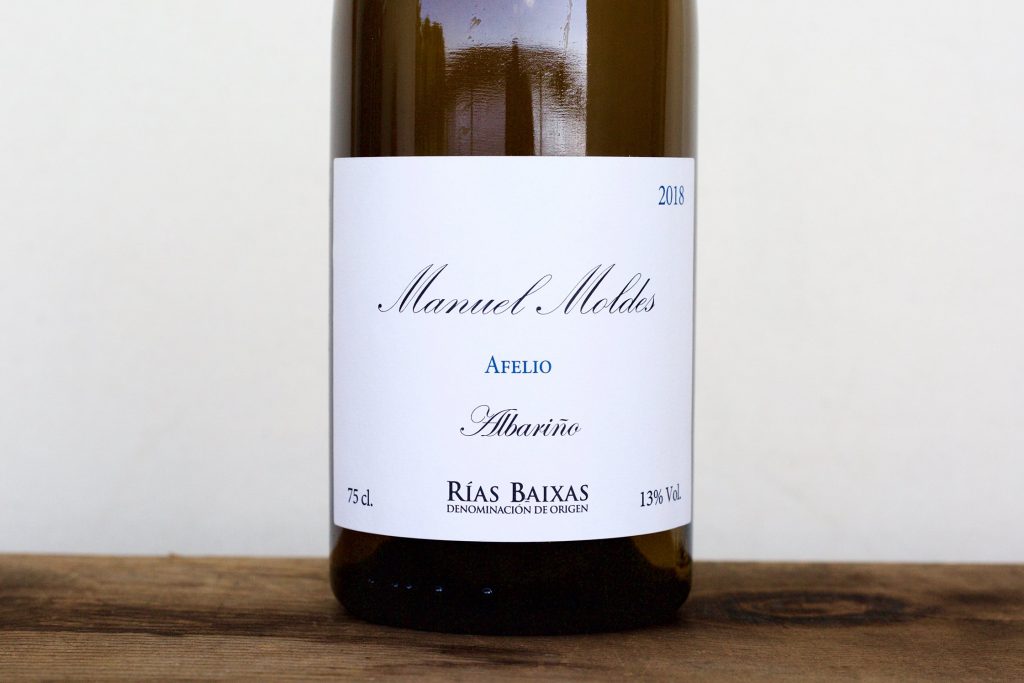

Manuel’s starting Albariño, Afelio, has made solid jumps from one vintage to the next and offers a value rarely matched for elegance and substance, though Arnaud Lambert’s Clos de Midi from our portfolio comes to mind. Afelio is a blend of dozens of parcels with an average age of over fifty years (2023). The parcels face in all directions at 15-90m on a mix of expansive terraces and flat plots on granite bedrock and topsoil. Over the years he gradually moved toward more aging in older barrels to polish its framing and lend greater depth and more subtle nuance to the wines compared to when they were raised exclusively in steel vats.

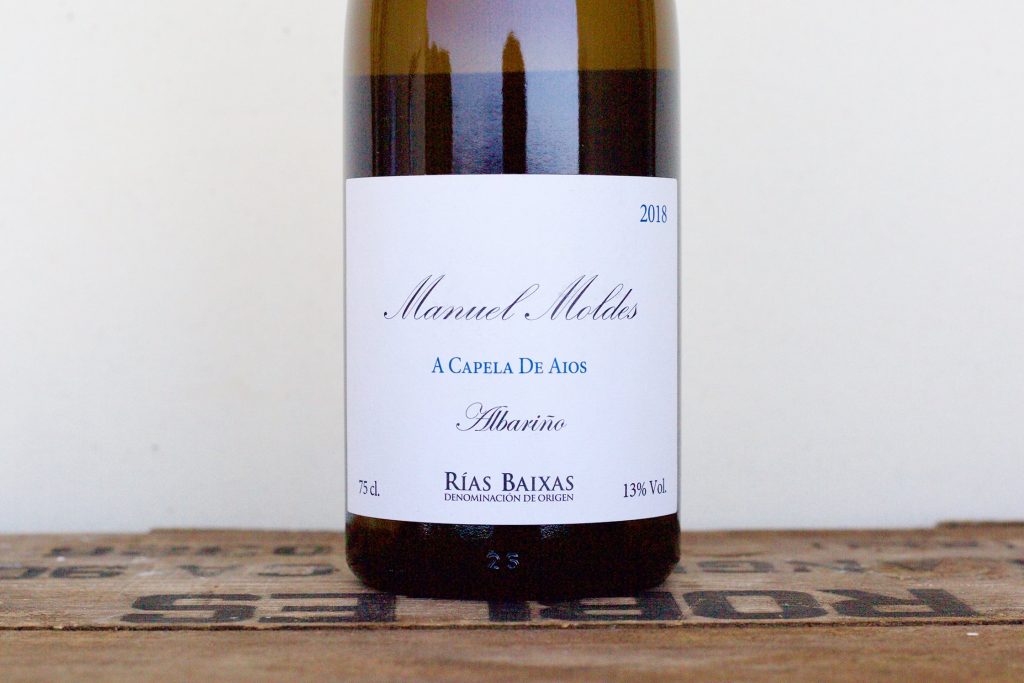

Manuel has made a habit of snatching up as many agreements with landowners whose vineyards are on schist as he can; it’s an extremely rare soil type for this part of Galicia where most of the land is granitic. Now, schist single-plot are the only Albariños he bottles as single-site wines while almost every other producer is bottling only granite-based wines. The original schist site in Manuel’s range goes into A Capela de Aios, which put Manuel on the map under his other label, Bodegas Fulcro, where it’s labeled as “Fulcro O Equilibrio.” Tasted next to Afelio, one might think it was a different variety if it wasn’t for the consistent high citrus notes and ripping acidity that few white wines maintain while remaining completely balanced and delicious. It’s fuller in body than Afelio (and most of the range) and more deeply salty, more metal than mineral, and slightly more amber in color. One could say they almost are as different as Loire Valley Chenin Blanc grown on schist and those grown on limestone. It comes from a south-southwest facing terraced vineyard at 80-90m planted in the 1940s and 1980s on fine-grained pure-schist topsoil and bedrock. As with all the wines, it goes through natural fermentation, and like the other “parcela” wines, it’s aged in old 500-700L French oak for 9-11 months.

The newest vino de parcela is Peai, pronounced the P.I., as in Magnum P.I.—a TV reference that may be lost on some of our younger colleagues in the wine business—sorrynotsorry. Made similarly in the cellar to A Capela de Aios, Peai comes from a west-facing terraced vineyard at 65-70m with 40-45-year-old vines on rocky and coarse schist topsoil and harder schist bedrock, while the bedrock of A Capela de Aios, by contrast, is severely eroded and softer. Peai is notably more structured and broader-shouldered compared to the other wines in the range; referencing white wines, think of Tegernseerhof’s burly Kellerberg compared to the gentler Loibenberg, or Veyder-Malberg’s beefier Buschenberg compared to the fully structured but finer Brandstadtt. Peai’s first year bottled alone was with the stellar 2020, and this 2021 is only an inch up in quality because there was only an inch of daylight to start with from the inaugural vintage.

On the subject of the rarest soil types in Rías Baixas, As Dunas is perhaps the most unique of all. Comprised of a few adjacent parcels that are less than a kilometer from the beaches west of Sanxenxo and Portonovo on pure schist sand, it’s like a beachfront dune—fine-grained, as much desert as a beach. On a soft slope, it was acquired only recently (first bottle vintage 2019) and the grapes were split between Manuel, Rodrigo Méndez, and Raúl Pérez. I believe these are now the three most expensive white wines in Rías Baixas, with Manuel’s maintaining the best price of the bunch; however, it isn’t the third rung in quality—that’s for each taster to decide, if bottles of each of these rarities can be found in order to make the comparison. The parcels are on that gentle slope, facing south-southwest at around 50m, originally planted in the 1940s and 1990s. As Dunas is deep, and showcases a broad range of delicate aromas, with some of the more distinguished veering slightly toward sweet balsamic notes, sweet mint, and exotic spices, on a surprisingly structured frame for a sand terroir.

Perhaps the original cornerstone of our company is Arnaud Lambert. He remains one of the three growers still left from the original roster of French wines imported in our first year; the other two being La Roubine and Jean Collet. There are also fewer growers we’ve written about more often than Arnaud Lambert, so I will try to keep this portion of the newsletter short.

Always in high demand are Arnaud’s Crémant Blanc and Crémant Rosé. They are a great value and deliver on quality and price, like all of Arnaud’s wines. Due to the chalky, sandy soil and cold climate, Saumur has always had the potential to deliver high-quality bubbles, but the financial incentive to compete with Champagne never materialized. The cost of production for serious wines would be more or less the same, and Saumur could never compete on price, though it can also be said that the cost of land is much more expensive in Champagne. Compared to Champagne, Arnaud’s Crémants have a gentle and inviting rawness and simplicity because they’re aged in steel for six months then bottled, dosed between 4-8g/L, and aged for a short time prior to release. Like most Crémants across France, they are typically relegated to by-the-glass programs, and there are few (I don’t know of any, really) that maintain a useful place on a bubble list in the middle price range. Believe me, we’ve tried to sell Crémant bubbles between Champagne prices and those that fit the by-the-glass price range and they move at a glacier’s pace, which is still slow despite climate change. Due to the smaller allocations of the past, the wines have mostly been on lockdown with many accounts. This year we have more, so if you want a piece of the action, tell us sooner than later.

After asking for a by-the-glass option for those who are priced out of Clos de Midi (or are short on allocation), Arnaud offered us the 2022 “Les Parcelles.” This 100% Chenin Blanc is labeled as a Vin de France because Arnaud supplemented the cuvée with some Chenin outside of Saumur due to all the frost damage in 2022. However, it’s still composed of 85% of the young vines from his top parcels and is aged in steel for six months prior to bottling. Given the pedigree of that 85% (and you can be sure that Arnaud is buying top-quality fruit if he has to buy), this wine is another steal.

Formerly known as Clos de Midi, the 2022 Midi has also arrived. The authorities in France have begun to enforce a new rule that limits the labeling of wines with a clos, most likely to protect the concept of the word from overuse. Surely there’s a lot more to this story, but in any case, all of the vineyards labeled as a clos chez Lambert were all historic walled vineyards. We could sell a thousand cases or more of Midi every year, but we don’t have nearly that quantity; it has become one of our most pursued wines because of its quality for the price. It’s always tense and ethereal, and, like Manuel Moldes’ Albariño “Afelio,” it simply over-delivers on expectations and shines in terroir expression. It also doesn’t hurt that it is one of the region’s most celebrated crus and drinks far too easily.

Montsoreau is a special wine Arnaud makes exclusively for us. Initially, we committed to only a couple of barrels each season but recently asked if we could have more to make up for our reduced allocations of Clos de Midi, and this increase should come about in a couple of years. The newly arrived 2018 was somehow overlooked along the way and we were finally able to bring it over. This parcel comes from a specific plot in the Saumur-Champigny commune Montsoreau, just next to the Loire River about 500 meters from the limestone bluff overlooking the Château de Montsoreau. While much of this plateau has a deep clay topsoil before the white tuffeau limestone bedrock, this small plot is almost pure white with a thin tuffeau sand and rocky topsoil with tuffeau bedrock, which makes it perfect for Chenin Blanc. Because I’m a big fan of Chenin aged in neutral barrels and for a shorter period after finishing primary fermentation, this wine was aged for one year in old French oak barrels prior to bottling. Montsoreau is usually more powerful than Midi and closer to his Les Perrières bottling from the Saint-Cyr-en-Bourg hill. I wouldn’t wait long to try to claim a case or two of this wine, since he makes only 48.

Like Midi, Mazurique is one of Arnaud’s most coveted wines because it’s a red that delivers well beyond what’s expected of its price. The coldest of Arnaud’s red crus, it stylistically lands somewhere between a low-alcohol, high-altitude Beaujolais, and a Hautes-Cotes de Nuits Pinot Noir, minus any oak—only steel here. Mazurique’s varietal characteristics are more subtly delivered than many young, high-pedigree Loire Valley Cabernet Franc, and its shallow rocky topsoil of sand and clay on tuffeau limestone bedrock renders an expansive but finely textured palate in full harmony with its spirituous nature.

To have Arnaud’s Mazurique and Les Terres Rouges in a tasting together is to witness a clear demonstration of the merit of soil terroir in wine. Both are made the same in the cellar and are harvested from vines with an average age of about 45 years and raised only in steel with almost a full hands-off practice on extractions during fermentation. They are almost within view of each other, with most of the parcels of Les Terres Rouges on the Saumur-Champigny hill, Saint-Cyr-en-Bourg, facing Brézé across the way, where lies Mazurique. Even though Les Terres Rouges has no red soil (as the name might suggest it does) it’s a light-brown clay and sandy topsoil on tuffeau limestone bedrock. While Mazurique can be found in the clouds, Les Terres Rouges is more earthy and richly fruited. For some reason, perhaps the greater clay content(?), all of Arnaud’s Saumur-Champigny wines from Saint-Cyr-en-Bourg are darker, rounder, fruitier, and more accessible when young than those from Brézé only a kilometer or two across the way. Brézé wines (the reds labeled only as Saumur) are almost always redder hued than black, though with plenty of darker shades. They’re more vertical than horizontal, in need of more time in the bottle, and more time to express themselves when first opened, compared to the Saumur-Champigny wines.

Hailing from Brézé on a mix of orange clay and coarse, microscopic shell-filled sand on tuffeau limestone bedrock, Clos de l’Étoile is indeed the star of Arnaud’s Cabernet Franc range; that is if one is in search of his fullest and most age-worthy wines. Its complement from Saint-Cyr-en-Bourg across the way, Saumur-Champigny “Clos Moleton,” is vinified and aged the same with 30 months in barrels and then another six in bottle before release. Moleton, as previously explained about the differences between Brézé and Saint-Cyr-en-Bourg, is fuller and rounder than l’Étoile, but not by much. Perhaps a regular note of difference between them is the tension and slightly wilder notes and x-factor in l’Étoile. Based on tasting old wines from Arnaud and his father, Yves, before they had as great a level of craft as Arnaud has now, this is a wine that may age better than you and me, but will also deliver an enlightening experience upon opening now.