For the last two months, we temporarily reduced the quantity of wine we’ve been importing in response to California’s sobering six months of film industry strikes and a recovery that’s coming along slower than we’d all like. This month, however, we have a couple of boatloads en route from France and Italy. There aren’t any new producers to report (though there is a lot of news on that front, which we’ll get to at a later date) but there are a lot of new wines from some of our best producers. We’ve trimmed the newsletter down to five featured growers: Château de Tracy’s historic Pouilly-Fumé wines, Anthony Thevenet’s Morgon wines, Dave Fletcher’s starting block white, orange and two reds, Fliederhof’s gorgeously fine and lifted Schiava trio, and Davide Carlone’s Alto Piemonte range grown entirely inside the Boca DOC. More wines are on the way, but there’s enough here to keep your mind full of wine.

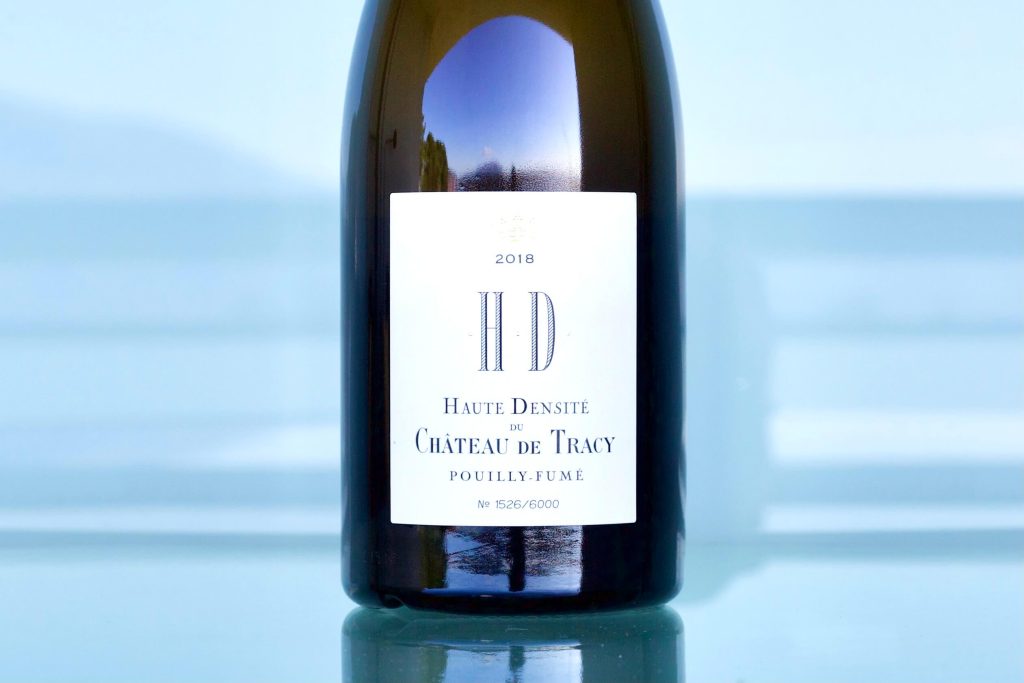

Along that famous target-shaped, Kimmeridgian limestone ring of the calcareous Paris Basin across Champagne’s Aube, Burgundy’s Chablis and into the Loire appellations, we first come to Pouilly-Fumé, and the riverside appellation’s most historic producer, Château de Tracy. In contrast to Sancerre, Pouilly-Fumé is less topographically extreme, with fields that roll gently as opposed to some of the neck-breaking slopes of spare soil exposed to the sun’s ever-increasing pressure on the other bank. The famous Kimmeridgian limestone marl of Sancerre and Chablis is present here too but, like Sancerre, Pouilly-Fumé’s other prominent geological feature is silex, known in English as flint or chert.

Château de Tracy’s position close to the river has richer clay topsoil and is more dominated by the limestone marl bedrock than silex. Because of the property’s history that extends back to the 14th Century, there is an unusual feature around their perfectly positioned vineyards that differentiates it from most of Sancerre and Pouilly-Fumé: verdant and wild indigenous forests that offer greater biodiversity and shelter from the heat, all preserved for centuries by the château. This forest is something rare having never been cultivated, leaving its precious nature and unique biodiversity intact.

Recently, Château de Tracy commandeered some vineyards outside of Pouilly-Fumé to offer a range of price-sensitive IGP wines with Pinot Noir and Sauvignon Blanc, and a classy yet upfront Menetou-Salon Blanc & Rouge. When looking for philosophically well-tended vineyards and exceptional value in the Loire Valley, and with Sancerre and Pouilly-Fumé almost out of reach for normal by-the-glass programs, Tracy’s IGPs and Menetou-Salons grown on the same general soil types offer excellent alternatives, with prices that turn back the clock more than a decade.

2022 Beaujolais could be the vintage with the most beautiful balance of juicy delicious pleasure and pure terroir expression for which we’ve waited almost a decade. 2014 was perhaps the last MVP vintage where everyone seems to have made their most consistent, predictable, and unrelentingly pleasurable wines with great balance, at least in my book. Anthony Thevenet’s 2022 Beaujolais wines are exactly that, and unapologetically sumptuous while maintaining classical form—a hallmark of Anthony’s style. With alcohols between 12.5%-14%, his 2022 range is gifted with one of the region’s oldest collections of vines that produce wines of joy and warmth; they smile at you, and you can’t help but smile back.

The 2022 Morgon and 2022 Morgon “Vieilles Vignes” bottlings mirror his 2014s with their slight purple over red fruit profile but with even a touch more body and juiciness—maybe chalk that up to ten years of organic viticulture, the wet previous year, and the sun of 2022. After his first solo vintage in 2013, he has come into his own with Lapierre-level consistency and purity, though the wines are closer to a Northern Rhône body while Lapierre’s hit closer to Pinot Noir country up north. We were able to snap up the last cases of his 2021 Morgon “Cuvée Centenaire,” harvested from vines that date back to the start of the United States Civil War. 2021s from growers with this kind of ancient-vine sappy density from this cool growing season makes for a wine with great refinement and depth. It may live forever—by Beaujolais standards—and would be best served with fewer participants (or more bottles!).

At the beginning of 2023, Dave Fletcher resigned from his full-time position as the head winemaker for Ceretto’s Nebbiolo stable. But they countered to keep him on as a consultant—good idea, Ceretto! The combination of fifteen years of experience and now much more focus on his own wines is reflected in the constant uptick of his range.

Dolcetto, like Grignolino, deserves a better position in the conversation among Piemontese junkies, though few growers take it seriously enough to attempt to distract the world from Nebbiolo’s most gloriously celebrated historical moment; after all, Dolcetto is known to be the most imbibed family dinner wine of the great Barolo and Barbaresco growers; they all know how great it is, so why don’t many others see it like they do? It’s grossly undervalued, and in the right hands, it’s the bottled joy of Piemontese culture, while Nebbiolo is more prone to capture its cultural pride. (As those in the trade know, one can still experience the greatness of a Barbaresco and Barolo producer’s wines they can’t afford by opting for their Dolcetto. At Bovio restaurant in La Morra, among the juggernaut Barolos of G. Conterno Cascina Francia, and G. Rinaldi Brunate, it was G. Rinaldi’s Dolcetto d’Alba that outmaneuvered the bunch.) Dolcetto is a perfect Piemontese restaurant by-the-glass wine, especially when a five or six-ounce pour fills the glass, initially stifling aromas of subtlety until half the wine is out and down the hatch. Even in an overfilled glass, Dolcetto has enough fruit and aromatic puissance to deliver its message. Dave’s Dolcetto is a pleasant shock that needs to be passed on to restaurant and fine wine store patrons in search of excitement and class, at a first-date price.

Despite our adoration for excitingly fresh and tense wines, Barbera’s naturally high acidity requires a longer development to soften which unfortunately results in higher potential alcohol, thus becoming a challenge for those looking to curb alcohol consumption and still drink a great Barbera. Its acidity is so naturally high, as the joke goes, that many growers spend much of August and September in church praying for the acidity to drop enough before rain comes, or the alcohol levels can rival Port (to return once again before the following year’s harvest for the next wave of prayers). To be honest, if I’m going to splurge with my liver, I usually reserve its high-alcohol allocation for wines like Barbaresco or Barolo (and on a rare occasion, Tequila). Yet during a tasting in mid-January, Dave’s 2022 Barbera d’Alba, with its cute new label depicting a train, was strikingly, lip-smackingly, hypnotically delicious, and hard to disengage from to move on to the rest of the exciting Barolos and Etna Rosso wines, and a spectacular new producer we’re signing out of Bierzo (more on that in a few months when the wines are en route!).

Part of the magic of Dave’s Dolcetto d’Alba and Barbera d’Alba is the bony-white, calcareous soils and the 60-year-old selezione massale planted at 350 meters altitude on an east-facing plot. The other contribution is Dave’s craftsmanship and nose for quality and style. Old oak is the practice for Fletcher’s reds, and no barrel is younger than ten years.

We also have minuscule amounts of Dave’s 2022 Langhe Chardonnay made in a Burgundian style (definitely an overused expression), which implies a dash of new oak–30% this year, spontaneous barrel fermenting, and harvested from vines on limestone soils (the latter of which legitimizes the comparison). His 2022 Arcato Orange wine arrived but there’s too little of this 75% Arneis and 25% Moscato blend, both destemmed but fermented and macerated with whole grapes for three to four weeks before pressing. The whites, like the reds, are exceptionally crafted. For a non-Burgundy Chardonnay, this one is about as close as they get (without the tinkering often slyly employed in New World Chardonnay with cheap reduction tricks paired up with dollops of new oak to blur the lines), and the orange is for all those who like their rust-colored wines with proper trimming.

While a troublesome name that translates to slave, Schiava, also known in German as Vernatsch, is the queen of Südtirol red grapes, and the young Martin Ramoser (still under thirty) orchestrates his Vernatsch-based St. Magdalener trio under biodynamic culture with the full support of his family in the vines and cellar. While the grape’s names are hard on the ears, it can render gorgeous wines; we’re thankful that Martin labels the two main players (both with 97% Vernatsch) with their special minuscule appellation, St. Magdalener! Following the line of the region’s greatest growers while already leaving his mark with his Gaia cuvée we start the range with the ethereal, red-fruited, and transparent, younger-vine 2022 St. Magdalener “Marie.” 2022 was a warmer vintage and the fully destemmed Marie captures nuances and the slight glycerol texture of the year’s heat but still blossoms with delicate fruit and flowers. Martin continues to capture each season with his viticultural approach of picking early to maintain ethereal qualities on top of what this regional profile tends toward, rusticity and earthiness (which we also like!).

A contemporary Vernatsch that touches Europe’s greatest elegance-led wine regions in style and class, the 2021 St. Magdalener “Gaia” is on its own level in Italy’s Südtirol. An entirely whole-bunch adventure first toyed with in 2020, the 2021 is just as hypnotic and charming and only a little more grown up. Relentlessly seductive, the 2020 Gaia made my top ten list of wines imported in 2022—unexpected for a Sütirol Vernatsch, but I remain quite fond of this grape’s humble elegance. Selected from the most perfect clusters from the most balanced vines of medium to old age, like the 2020, the 2021 follows in the line of Gran Marie and the nostalgia, though this time leading me to another great Gevrey-Chambertin grower I’ve never visited and can no longer afford (come to think of it I never could) with all its beauty and filigree trim; of course, only after the new oak was finally swallowed by the Gevrey legend’s wine, hours after being opened. New oak is not an issue here, only the remnants of a great terroir cultivated by believers and sculpted by an inspired young grower in two ancient Burgundy barrels with a vision for his wines, wines that are far from home among Germanic and Italian cultures, the Südtirol being both. The bottles allocated to us are too few and will be doled out sparingly to those who believe a wine’s price should be based on its performance rather than its appellation. This is a wine that transcends the perceived limits of what can be achieved with an unexpected terroir and an underdog vine variety.

Davide Carlone is so immersed in his day-to-day work that one could easily get the feeling he has missed the surge of global reverence for his wines. With so much going on, it’s hard to get out of Boca and his exposure to other great producers is limited, undoubtedly a consequence of being on the edge of a country in a very rural setting at the base of the massive Alps. Most notable is the nearby Monte Rosa, which is 175m short of the Alps’ tallest peak, Mont Blanc/Monte Bianco, though it’s much more pronounced and visible from the Po Valley. His wines find that elusive common thread shared among the range from great producers of precise craftsmanship (he’s also a blacksmith/metal worker) and big emotion—as though they shoulder the history of Boca and an obligation to reflect its true history in style and taste.

The globalization and stylization of wine (à la Burgundy and Bordeaux) remain strong and continue to infiltrate even Europe’s most historical regions, like parts of Spain, and Portugal, where some growers have quality terroirs but need direction—oh, how the dictatorial scars of the 1900s remain in Iberia! I like wines made with these tried-and-true methods (minus the new oak, please), however, they often neuter the cultural message. This is not the case at Carlone, which is why it fits in with one of The Source’s callings as an importer: to focus on cultural authenticity while maintaining responsible vineyard practices and conscious craftsmanship.

Few in the world know Davide Carlone, and I think he and his Swiss patrons are partially to blame. The Swiss love their neighbors’ mountain reds; their country is frozen most of the year, too cold to produce them. And what’s better in the freezing alpine territories for a hearty, warm dinner? (Beer works too, but we’ll stay on topic…) Davide is constantly building, expanding, and reclaiming Nebbiolo territory reabsorbed by forests and other wilderness after the economic viticultural failures in the early to mid-1900s that led to mass workforce migration to industrial centers. On his pink-flecked, light gray and volcanic bedrock that’s hundreds of millions of years old and sometimes resembles dinosaur bones, and his sandy topsoil, this expansion of his childhood reclamation dream comes at great cost in time and money. The Swiss (at least certainly those with the better taste inside this neutral bunch) make the windy drive and offer him on-the-spot hard-to-refuse cash in difficult economic times. Thus, the cycle of Davide’s relative global obscurity continues. In California, we’re gifted some limited quantities of his authentic treasures from the prime of his craftsmanship, which by all accounts starts with his meticulous vineyard work.

Piemonte’s golden age began decades ago and we’re right in the middle of it. Indeed, the region’s northerners are just getting traction while those in the Langhe were already in sixth gear decades ago. Broken links in this lengthy series of quality years exist and the culprit is often hail, as it was in the catastrophic May 2020 hailstorm. Luckily for Davide, the hail missed his vineyards entirely, making his wines some of the few available from the entire region. These south-facing vineyards perched above all Alto Piemonte appellations and surrounded by densely forested mountains facing the Po Plain were indeed quality fruit from a great season. You only need to experience his 2020 Nebbiolo new arrival!

We start with the 2022 Vespolina, a grape known for its potentially bitter green tannins, but not at Carlone. Spurred on by another local vignaiolo and well-known enologist, Cristiano Garella, Davide opted to shorten macerations to avoid digging too deep into the seeds and extracting the meaner tannins once the alcohol begins to break down the various membranes around the seeds. Vespolina is yet another unsung superstar-in-waiting from Piemonte, although it seems impossible for any grape, no matter how worthy, to challenge Nebbiolo’s unstoppable generational dynasty. Vespolina is known to be genetic parent material for Nebbiolo and shares its noble balance of finesse and power, at least when crafted by the right mind and hand. 2022 was a unique year and mirrors the general climate of the Langhe with balanced acidity, sun-touched ripeness and gorgeous red fruits tied together with a floral bow.

Quick out of the gates on a late Wednesday morning in early February this year, with clear skies and perfect cellar temperature inside and out on Spain’s Costa Brava, the 2022 Vespolina flaunted a gorgeous nose of flowers, clean lees (for those who have cleaned out a red wine fermentation bin, it’s those pinkish-purple creamy, glycerol lees pocked with brown seeds), licorice, carob, fresh cut and raw yam, horse saddle (not in a bretty way), straw, algae, and tree bark. It’s extremely young and juicy with a palate of beautiful chalky tannins—nothing green. It has a stunning savory finish with licorice and is tailored in a micro-ox style on the palate; a compliment considering this stainless steel raised wine, a vessel which typically makes wine more angular, though impossible to tell with this wine, save the striking clarity and clean trim. After a long lunch with some Spanish winegrowers and just before I passed out early, a retaste revealed the sweet black licorice note is stronger than earlier in the day; like the licorice note of a young Vieux Telegraphe CdP from the ‘90s and ‘00s—I haven’t tasted anything from Vieux Telegraph since 2007! Tannins are much tighter and the wine much more savory; blue and black fruits with a red fruit finish. Beautiful.

I have waited more than two years to finally experience a finished bottle of the 2019 Boca, which I have tasted twice out of botte and once out of steel vat just before bottling. Each encounter was glorious with an educational opportunity to taste separate vinification and aging of different biotypes. The final blend surpassed my expectations. This is a wine and a vintage for the ages, and while it will be good young with the right amount of patience and coaxing, it’s guaranteed to age very well. The most elegant and lightly aromatic Nebbiolos out of botte are reserved for the Adele bottling. In this bottling, labeled simply as Boca, all the many different old wood vats and a dozen or so Nebbiolo biotypes with a dollop of Vespolina (15%) makes for a deeply layered and complex wine that combines autumnal red and dark stone fruit and ripe wild berries, and an immense array of spicy, earthy, animally, savory qualities. This is as good as it gets for authentic Alto Piemonte on this type of hard volcanic bedrock. Carlone’s Boca seems to be in a league of its own up on this hill away from the greater production of Alto Piemonte Nebbiolos further downhill and closer to the expansive Po Valley. Bravo, signore!