Gen Z already at the helm of a Barolo cantina? Impossible, you say? Nope! Born in 1997, the first year of Z, the inspirational Daniele Marengo from Mauro Marengo, and Gino Della Porto, the soul-surfing, super-chill Gen X visionary from the establishment-rocking Nizza Monferrato, Sette, are about to invade California over the next two weeks. These two long-time chums will be a two-person road show, with Daniele flaunting his triumphant 2019 Barolos (crafted at a jaw-dropping 22-24 years old!), and Gino, Sette’s revelatory range after the biodynamic conversion six years ago of their lucky-strike purchase of old vines on a perfectly situated hill in Nizza Monferrato. The Barolo and Monferrato reboot is here, and these two are quietly at the front of the charge.

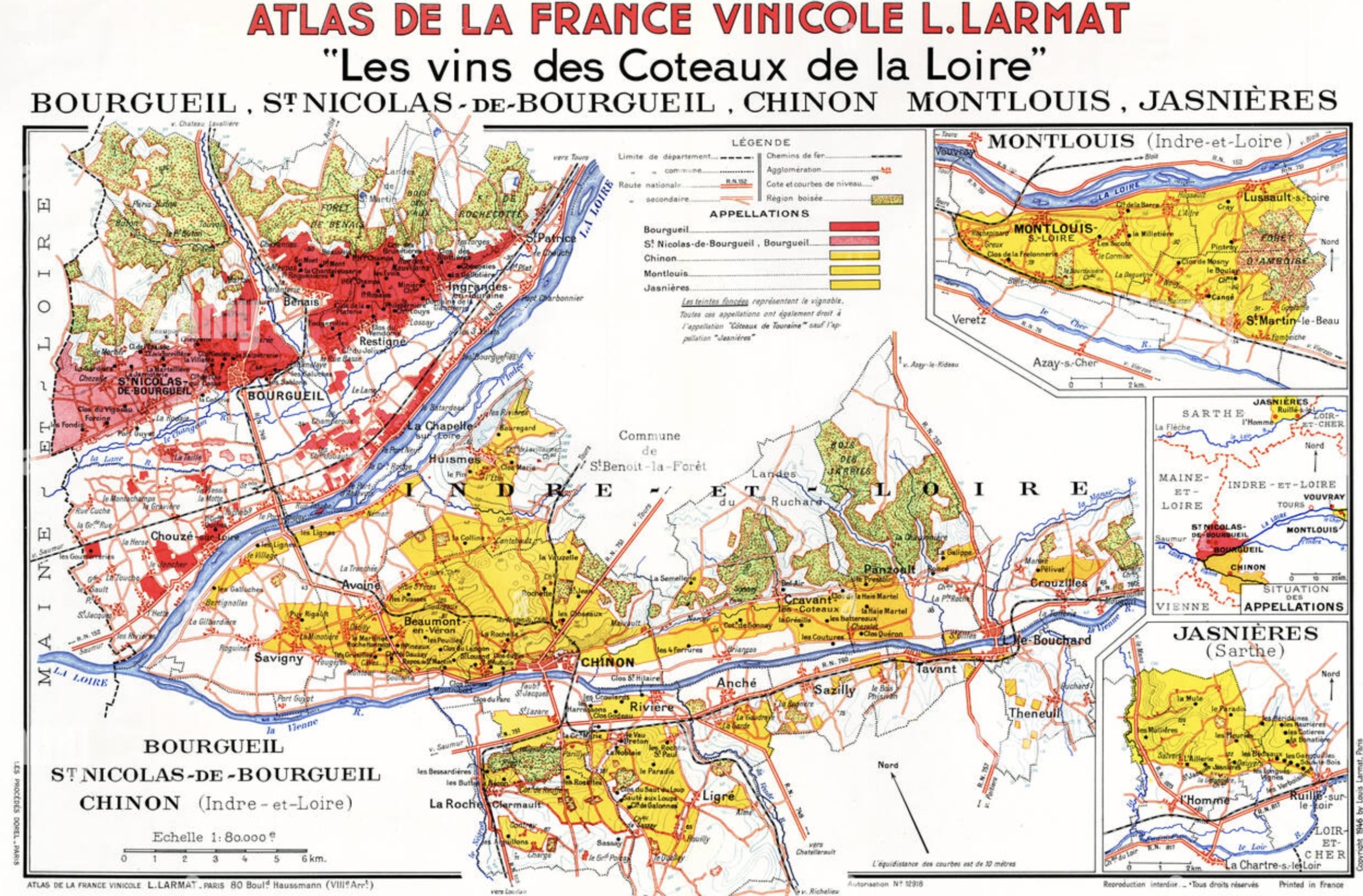

One producer I’m excited about this month comes from the humble and nearly forgotten Loire Valley appellation, Bourgueil. Operated for the last few decades by François Delaunay after his father handed him the reigns, the now organic (certified in 2013) Domaine de la Lande maintains spectacularly priced wines that simply overdeliver with an extremely classic sensibility. Full of flavor, François’ wines rewind the clock to my first encounters with Cabernet Franc, which, almost thirty years ago, was an esoteric variety in the States thought best blended rather than as a monologue performer. Cabernet Franc from Chinon, Bourgeuil, Saint-Nicolas-de-Bourgueil, Saumur and Saumur-Champigny remain some of the world’s best deals for legitimately great wines. Even the average ones are higher than the average from most famous appellations. The most common Loire Valley Cabernet Franc can age well, if not more consistently than most Burgundies two or three times the price. And while the wine world continues to flirt with new styles in each area and decade-long trends, some, like François, have wedded themselves to traditionally and simply made wines.

With the first sample bottles I received, I knew by the aromas alone—rustic but clean, deep, balanced between darkness and light—that they were for me. I admit, I’m an aroma hound first, texture second. My first visit with François this last December brought my enthusiasm to new heights, and my second only three weeks ago was reassurance that it wasn’t a fluke. My first cellar tasting last December was on point, followed by a quick vineyard tour of the well-tended and thriving grounds, still green even in December. But it was in the ancient tuffeau cave with old bottles that I understood the true quality of this domaine and was reminded of the breed of Bourgueil.

At the top of the slope near the forest, we pushed through thick bushes, ducking under an overgrown tree and into their hidden cave. Entombed in the milky white tuffeau cavern were vintages as old as François, with bats quietly sleeping before slowly unraveling like old wines as they stretched before flight. As with many of us, one of my greatest pleasures is old wine that’s still sound. Well-aged wine is the final frontier of wine appreciation, a test of pedigree and clairvoyance (and sometimes vindication) of its maker. Most “taste” old and celebrated wines with too many people for a single bottle, which works as an academic snapshot, or often to fluff their experiential inventory to be later embellished in recounting, as though a taste is enough to know a wine. “Tasting” a great bottle is wasting a great bottle. Great wines reveal their merit when drunk over enough time—at least until the conversation starts to go downhill. The worst tastes of a great wine are the first, or the mud in the bottom. It’s everything in between over a time where one really gets to know a wine’s true character and breed.

I’ve long collected wine to age. In the late 1990s, I worked at Restaurant Oceana in Arizona, with its chef, Ercolino Crugnale. He moved there from California with an extensive collection of mostly California wines he intended to put on his wine list, only to find out that he’d have to sell them to a distributor first and have them sell them back to keep things legal. He decided to drink them all instead. He was, without a doubt, the most generous restaurant owner I’d ever worked for. He had all the California greats from the 1970s-1990s, the highlights for me being Ridge and especially Williams Selyem. His pleasure was sharing as much as drinking the wines themselves. And we definitely didn’t taste. We drank. And that’s when I fell in love with old wine. Williams Selyem was the first great influence after flirting with the world of cheaper wines—the price point I could afford to drink. I was fortunate to spend a lot of dinners in Santa Barbara and Sonoma with Burt Williams, from Williams Selyem, during his last five years when he brought out mostly magnums because he’d run out of 750s. Darn.

In the mid-nineties, young and ambitiously curious wine freaks like me weren’t easily allowed into the exclusive “wine club.” I was dismissed regularly by older wine professionals who guarded wine knowledge like gatekeepers, bestowing to the worthy (but moreso those who kissed the ass the most), or to the guests they schmoosed. Never one to kiss the ring (and not so humble about it either) I walked my own path until I met Ercolino. The other most generous boss I ever had was The Ojai Vineyard’s, Adam Tolmach, with whom I worked in the cellar for five seasons and remain good friends.

There are few wine experiences like old wines crafted by generations past that then go unmoved in silence and darkness for decades deep inside the cold, damp earth. It’s incredible to think that some of the wines that had been guarded perfectly for decades before François opened them were destined for my glass that first day I visited Domaine de la Lande. It’s humbling, and a special privilege that I can’t say I felt I deserved. Yet, I could cite countless examples of having experienced that sort of kindness and hospitality in the wine world.

Back in Portugal, I messaged François about possibly buying some old wines—a mixed case or two, I begged … I could see François’ lean, rosy high cheeks pressed up as he smiled and typed a mile-long list of options with every vintage back to 1982 that he sent me a few days later. The list was thorough, the prices jaw-dropping—a mere $0.50-$0.65 for every year aged in the cellar; top years, $1.10 for every year. I scoured the web for vintage charts but came up short on information for Bourgueil. I asked for guidance, which François gave. I proposed four mixed cases off his list: some very old that I would try immediately and other young ones (2005-2015) that I’d cellar longer. So far, I’ve pulled the cork on about ten bottles (1985, 1988, 1989, 1990, 1993, 1996, 1997, 2001, 2002, 2005–and there may be a couple I’ve forgotten), and each has been glorious. Most I shared with our Portuguese grower and great friend, Constantino Ramos, who is also now obsessed with them. The only confusing moment is just after the cork is pulled. No bottles had been capsuled until François’ family readied them for me; they’d all been left exposed to that ancient cellar, some for as many as four decades. The top of each cork was moldy and smelled like the deepest corner of the cellar and even a little TCA, quite rotten. But none of the wines were corked! The bottles only needed their lips and inside the neck cleaned, where the cork was in contact.

Bourgueil has long been overshadowed by Chinon, at least in the US market–maybe because it’s easier to pronounce? With all those vowels, Bourgeuil is tough to get right! Bourgueil and Saint-Nicolas-de-Bourgueil (SNdB) are on a contiguous slope on the north side of the Loire River. Chinon is more topographically diverse and mostly sandwiched between two rivers (the other being the Vienne), like Montlouis-sur-Loire’s vineyards are between the Loire and Cher. Perhaps Bourgueil is viewed as more rustic than the typical Chinon. Perhaps a matter of more gravelly and sandy sites in Chinon?

Without a classification system in place, location is an important variable. The pedigree of each vineyard bearing this appellation name can be quite different from the next. There are wines for easy drinking and others far more serious. Looking closely at a Google Earth image, or an appellation map, the land near the Loire River has fewer vineyards than other crops.

Bourgueil is split in two by the small creek, Le Changeon, and from a 20,000-foot view, along with the SNdB, the contiguous slope is like the Côte d’Or and many Champagne areas, only facing south and southwest. Many of Burgundy and Champagne’s top spots favor more eastern expositions. Given its abundance of pyrazines, Cabernet Franc historically required more late afternoon sun, so more south/southwest positions. These days, it ripens quite easily regardless.

The lower slopes of Bourgeuil and SNdB are generally sandier, and those on the riverbank have more unsorted alluvial sand, silt, clay, and gravel. About 4km north of the Loire River toward the forest, a gentle uptick begins from 40m, peaking around 90m. The top sites for wines of pedigree sit higher on the slope, close to the forests, where roots make contact with more of the tuffeau limestone bedrock and calcareous clay. François’ family vines begin just north of the village on the western end of Bourgueil at about 50m with more clay than sand and move upslope with the oldest vines destined for the “Prestige” bottling.

In short, the Bourgueil comes from six hectares planted between 1965 and 2010 at 50-60m facing south on a gentle hill of tuffeau limestone bedrock with a shallow siliceous clay topsoil. This is the easier-going wine, fresh, beautiful, and lifted with a substantial follow-through. It’s a great wine that will improve your day when you need a fair-priced, terroir-laced organic wine that doesn’t make you work too hard to find its cultural and regional stamp.

Lucky for you, we were able to buy both the 2015 and 2017 Bourgueil “Prestige.” This is their superstar wine from two excellent and balanced vintages (from the same vineyards those old wines that I bought from François grew and then aged so long in the cellar). They are also their current releases—it’s nice to have some age built into a wine program! Prestige is more profound and substantial than the appellation wine. It’s equally classic in style, and just as fun to drink, but in a heavier weight class (though more a tight-lipped-but-fluttering Ali than a bruising Tyson) flowing with waves of complexity. Also facing south on a gentle hill of tuffeau limestone bedrock with deep calcareous clay topsoil at around 70m, this two-hectare plot was planted between 1930 and 1964. These old vines give it its torque and the organic culture for more than two decades now, its vivacity. The 2015 is for those who want more meat on the bone, while the 2017 is only a little more lifted and still quite substantial.

All François’ Bourgeuil wines are made in a very straightforward manner. They’re fully destemmed and fermented/macerated for around two to three weeks with one punch-down and one daily pump-over. Then they’re aged 18 months in old 5000 L French oak foudre and steel, with light filtration but no fining.

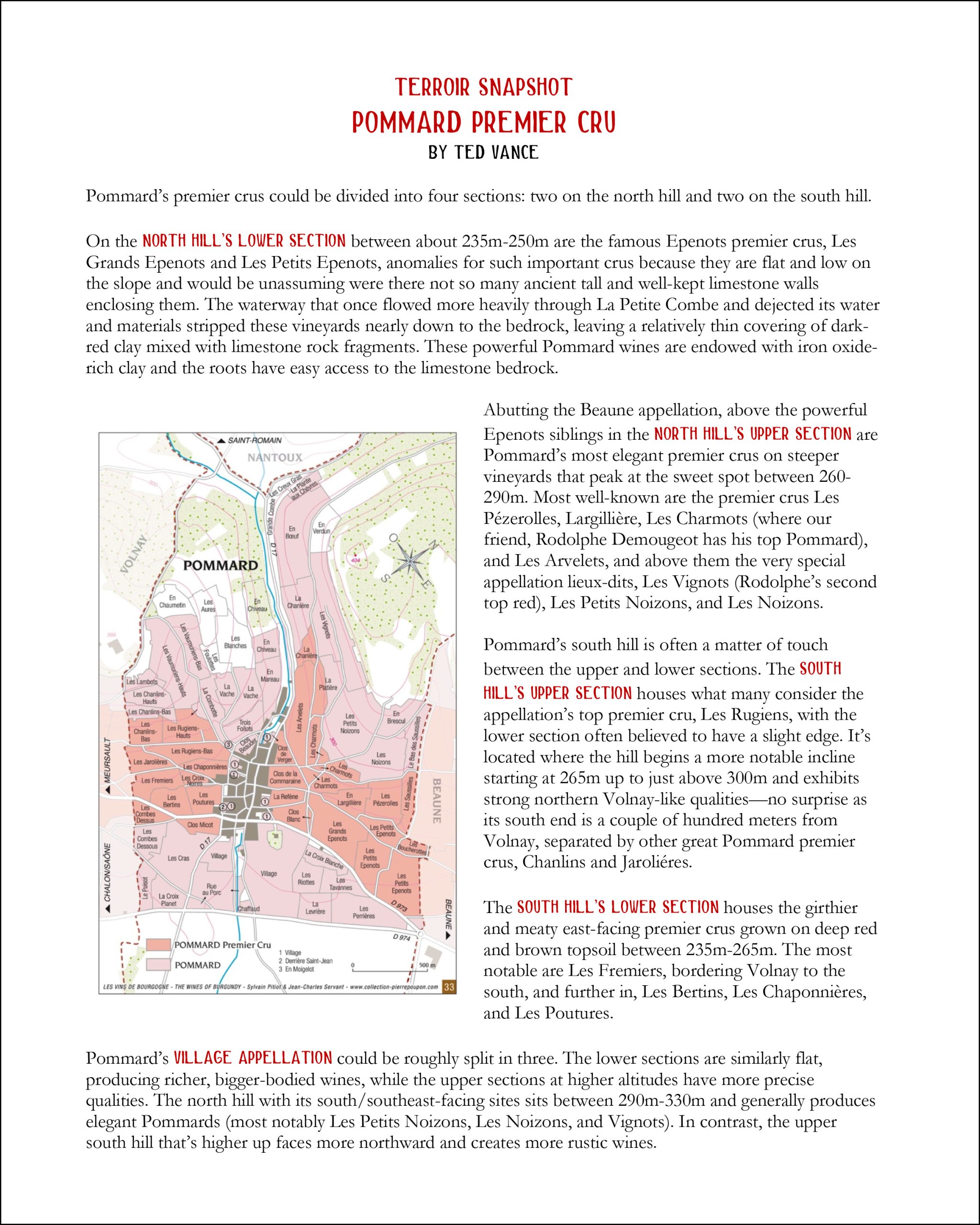

Speaking of nice guys making wine in a similarly straightforward way as François Delunay, Rodolphe Demougeot takes his humble (by Côte d’Or standards) scatterings around Beaune, Pommard, and Meursault to peak performance for their classification—a subjective hierarchy in the face of climate change since we don’t all see eye to eye in our preferences. Unless someone else is paying the tab I’ll often take a young, higher altitude premier cru above a grand cru.

Demougeot’s vineyards are either high or low, with hardly anything mid-slope: two premier crus, Pommard Charmots and Savigny-les-Beaune Les Peuillets, among eighteen different bottlings, no grand crus. It’s not Mercurey-level humble among the hierarchy of Burgundy areas, but it is modest considering his surroundings overlooking Pommard’s top Epenots premier crus on the north hill, paces below and above Meursault’s top premier crus and in the vast expanse of Beaune, with its swarm of négociants and tainted reputation. He does the best with what he’s got, and his best are charming and finely tuned. I’m a fan because, like I always say, I love honesty and less hand in the wines. As mentioned in a previous newsletter, when traveling in Burgundy with the Austrian luminary, Peter Veyder-Malberg, Rudy’s wines topped his list. Purity and sophisticated simplicity won him over, and we visited a lot of excellent makers.

Yes, it was hot. But … How about some perspective without the spin? It wasn’t exactly hot like other hot years. There were so many heat waves in the spring, summer and fall of 2022 but there was also at least some healthy rain at crucial times in Burgundy. 2021 was a cold and wet year, and hot seasons following cold ones always benefit from less hydric stress because reserves are topped up, especially in limestone and clay-rich lands. This was felt all over Europe, which makes 2022 compelling enough to bet on. This didn’t happen so well for the string of hotter years that started in 2017 and was bookended by 2020, though 2017 also benefitted from some seasonal particularities (cold and wet until the summer went nuclear) and a colder year prior. This filled 2017 with some playfully serious wines with classical trim and their terroir clarity fully intact. 2017 remains my go-to red Côte d’Or drinking vintage since 2013, though the 2014s with their often hollow interior are filling in, and the furrowed brow of 2015 has begun to loosen. Let’s see what happens in the years to come with the 2018-2020 vintages.

At the risk of being dismissed as having a house palate, I admit to being very happy with our two main Côte d’Or growers in these hot years. They delivered fresh wines of low alcohol and a well-managed structure. I have a fortunate history of steadily following most of the same producers as a Burgundy lover since the release of the 1999 vintage, until the wine industry lost its mind on certain domaines. Coche and Roumier used to be about the only small domaine Côte d’Or unicorns with hefty second-market prices, but now there’s an uncountable amount. Before the zombie buyer searching for unicorns who had more dollars than sense showed up, guys like Demougeot took over his family’s domaine and nobody cared because he didn’t have top premier crus or grand crus. And Duband was under severe scrutiny for big ripeness and extraction and lots of new oak, which he then drastically recalibrated and has since evolved into one of the finest top values on the entire Côte. France’s top wine publication, La Revue du vin de France, went so far as to put him in the same sentence as Leroy.

Let’s face it, while many regions benefit from newfound positive ripeness where it was once impossible, Burgundy is facing a climate change dilemma more quickly harrowing than most—it’s particularly existential for those in the prime historical spots. Aside from the new challenge of frost and hail almost every year, the solar beatdown on what makes it to harvest is off balance compared to what it once was.

The phenolic balance of Burgundian Pinot Noir and Chardonnay has always teetered on a knife’s edge.

Other French red varieties in more continental climate environments such as the Cab family and the Rhônes, get away with more acceptable variation in some sense (except when the alcohol is too high), and the varieties are sturdier. But when Pinot Noir loses its flowery palate freshness or the growing season is too fast, forcing shorter and/or softer extractions during fermentation, they may maintain acidity by being picked early, but they’ll lose their magnitude. Chenin Blanc, unlike Chardonnay, has a history of tensile-dry wines and sticky sweets successfully grown at world-class-quality levels on just about every soil type. Its chameleonic quality is more resistant to the immediate weather challenges at hand. But when Chardonnay is picked prematurely in a warm year it gets bitter, and when picked late its flat and feels prematurely aged in bottle.

The truest statement about navigating Burgundy still stands (for now): Buy the producer, not the vintage. The amendment to that rule should be to follow producers working on a more human scale with less surface area that are personally in daily contact with their vineyards. Slight adaptations during the growing season make the difference on that knife’s edge. And that brings us to Rodolphe Demougeot, who works in his vines all day and leaves his wines in tranquility until bottling.

These will go as fast as they have been lately, since our fan base in California began to see the light of Rodolphe’s wines a long time ago, and his 2022s are about to land. First in the hierarchy … We have the Bourgogne Côte d’Or Chardonnay and Pinot Noir. (Which I think they could’ve shortened by leaving out Bourgogne…) These two wines are a case in point for Rodolphe’s talent with lower classification wines built like a Champagne flute rather than the slightly audacious Zalto Burgundy stem. The Chardonnay is a blend of different parcels from high up on the slope above and below Meursault. This combination delivers a wine with a somewhat mid-slope weight and richness (lower site) and minerally lift (higher site). It’s a great starter white and tastes as much like a Meursault as, well, a Meursault. This isn’t too surprising since it’s located in Meursault! The Pinot Noir comes from old vines near Chassagne-Montrachet, an appellation formerly more famous for red than white. It’s a serious ferrous red Burgundy, without the lipstick.

Rodolphe has done all of us terroir junkies a favor by presenting almost all of his appellation wines with their respective lieux-dits. This way, we can still contemplate and play with terroir without selling Mom’s jewelry to get familiar with Burgundy’s terroir mapping.

Let’s start in the north with Savigny-les-Beaune and work our way south. Savigny-les-Beaune is a diverse appellation and probably less famous than it could be. The diversity of its parcels divided between two main hills spread far and wide with so many expositions (southwest to north-northeast) and deliver unexpectedly high-quality wines. Outside of the local luminaries, like Simon Bize and Chandon de Briailles, many great to very good growers from other appellations (like Leroy, Bruno Clair, and Mongeard-Mugneret) have planted flags in the appellation and on the south hill with sites facing as much northeast as east on the same slope of Rodolphe’s two wines, Les Bourgeots and the 1er Cru Les Peuillets. These are adjacent, with the former a more gravelly alluvial wash from the now creek-sized waterway, and the latter, farther from the creek, built with more sand than gravel. Les Bourgeots is often grittier in texture and darker, while Les Peuillets is brighter and more lifted.

Jumping over the freeway and to the south side of Beaune, Rodolphe has the Clos-Saint-Désiré, a Chardonnay harvested from a soft slope with deeper topsoil than expected so high up. It’s crafted in the cellar the same way as his Meursaults but it doesn’t taste like Meursault, beyond the variety and the more general region. It has bigger shoulders and is more frontloaded, while the Meursaults have that ingrained finesse and specific Meursault minerally magic. Rolling downhill just to the main road shooting out from the south side of Beaune’s town center, is Les Beaux Fougets, a red Burgundy. I’ve always loved the texture of this wine; it’s a rich Pinot Noir with a lot of earth and density yet remains lifted and lightly exotic by Rodolphe’s touch. Like many of his other reds, they often open with some reductive elements but quickly move into a more open expression.

In photos, Rodolphe looks rough and tough, and though he might be tough he’s not at all rough. He’s gentle and generous, thoughtful and accommodating, an unstuffy Burgundian with a soul surfer’s demeanor unless he’s talking about organic certification, which furls his brow and thickens the air. He works organically but doesn’t certify because he, like many in France, doesn’t believe in the paper shuffling certifications. Auditors don’t go to the vineyards. They focus on receipts to see what makers have bought. Not sure that’s the best metric … Ever heard of cash purchases?

The next commune to the south is Pommard. Like Savigny-les-Beaune, it can be a difficult village to navigate because of its many faces. Rodolphe’s appellation Pommard is one of the few non-lieu-dit wines as it’s a blend of two parcels in very different areas, like his Bourgogne Blanc and Meursault. A blend of unusual names, La Rue au Porc and En Boeuf—in English, they could be loosely translated as The Pork Street and In Beef. (There is also a Pommard climat outside of Rodolphe’s collection called La Vache—the cow. When they were classified in 1936, Pommard clearly had a few jokers on their marketing team; perhaps these names were chosen to stimulate digestion, and I guess we know why Rodolphe didn’t bottle them separately as lieu-dit wines … ) La Rue au Porc was planted in 1948 and composed of deep clay and limestone rock topsoil—the sources of the muscle and weight of the wine. En Boeuf is located in the Grande Combe, a somewhat narrow valley far to the west of the appellation on the north hill facing south on a steep slope of shallow rocky topsoil, close to forests, and in the direct path of colder winds from the countryside to the west, which presents an almost complete contrast to La Rue au Porc. Planted in 1979, the position of these vines brings the balance of mineral, tension, cut and lift, to compliment the richer fruit and fuller body from En Boeuf. Compared to the other Pommards of his range, this is more savory and meaty, while the others are more lifted and ethereal.

Moving away from vineyard names with animals and on to more sexy, Pommard “Vignots” is not part of the upper cru club, but of cru club quality, thanks to climate change. Perhaps it was left out mostly because of its altitude which more or less begins at 300m on Pommard’s north hill. Vignots is a phonetic portmanteau of vigne and haut, which means, high vines. In communes with grand cru wines, above 300m usually defaults to a premier cru or appellation wine. But in Pommard, where there are no grand crus, the default goes to either village or Bourgogne. Regardless, Vignots is a serious wine, especially today. (Lalou Bize Leroy knows it, Vignots being one of her domaine’s bottlings.) It leans toward those of us who often appreciate as much angle in our Burgs as curves. Rodolphe’s 0.21ha parcel was replanted in 1983. Its defining characteristics of being south-facing, higher altitude, windy and steep, with thin topsoil and limestone bedrock are on full display after his soft approach in the cellar and rigorous organic vineyard work.

Though its full name is a bit long, we’ve finally arrived at an A-level marketing decision on the name of Rodolphe’s top red: Pommard 1er Cru Les Charmots “Le Coeur des Dames.” I.e. High Charm, “The Heart of the Ladies.” Now that’s more like it, Pommard marketing team! Here, we flip Vignots upside down by leading with more curves than angles. Nature abounds in this small clos enclosed by limestone walls that keep out the diesel and brake dust from the surrounding roads. The vines here are plowed by horse as much as possible to respect the microbial life in the soil while also maintaining control of the natural grasses and weeds. Purity, elegance, and nobility are consistently defining factors rendered from this hillside planted in 2001 on limestone and clay. It’s made the same way as Les Vignots, which makes for a clear two-bottle demonstration of terroir at play with two of the most elegant faces within Pommard’s diverse range of terroirs and wine styles. Both are softly extracted through the infusion method, which is to say very little is done in the way of punch-downs or pump-overs during fermentation. I love this style because I subscribe to the idea that if the terroir is strong it doesn’t need to be forced to deliver its message.

Last but not least of the reds and the furthest southern Pinot Noir vineyard in Rodolphe’s range, aside from the Bourgogne Rouge, we finish the red set with the Auxey-Duresses Rouge, “Les Clous.” Harvested from a single acre of Pinot Noir planted on a direct south exposition, it’s perfect for this appellation which is sometimes cooler than the rest of the Côte. Tucked into a small valley back to the west of Meursault and scrunched between Monthélie and Saint-Romain, this is a smart buy in warm and healthy years, like 2022. The soils are limestone and clay, but are very well drained due to the ample mix of stone sizes deposited by the small creek that once flowed through this valley long ago. Earthy and foresty freshness with a long finish are its lead characteristics thanks to the depth of the vines planted in 1949. Though more fruit-driven in 2022, it remains restrained and savory, a lovely match for food.

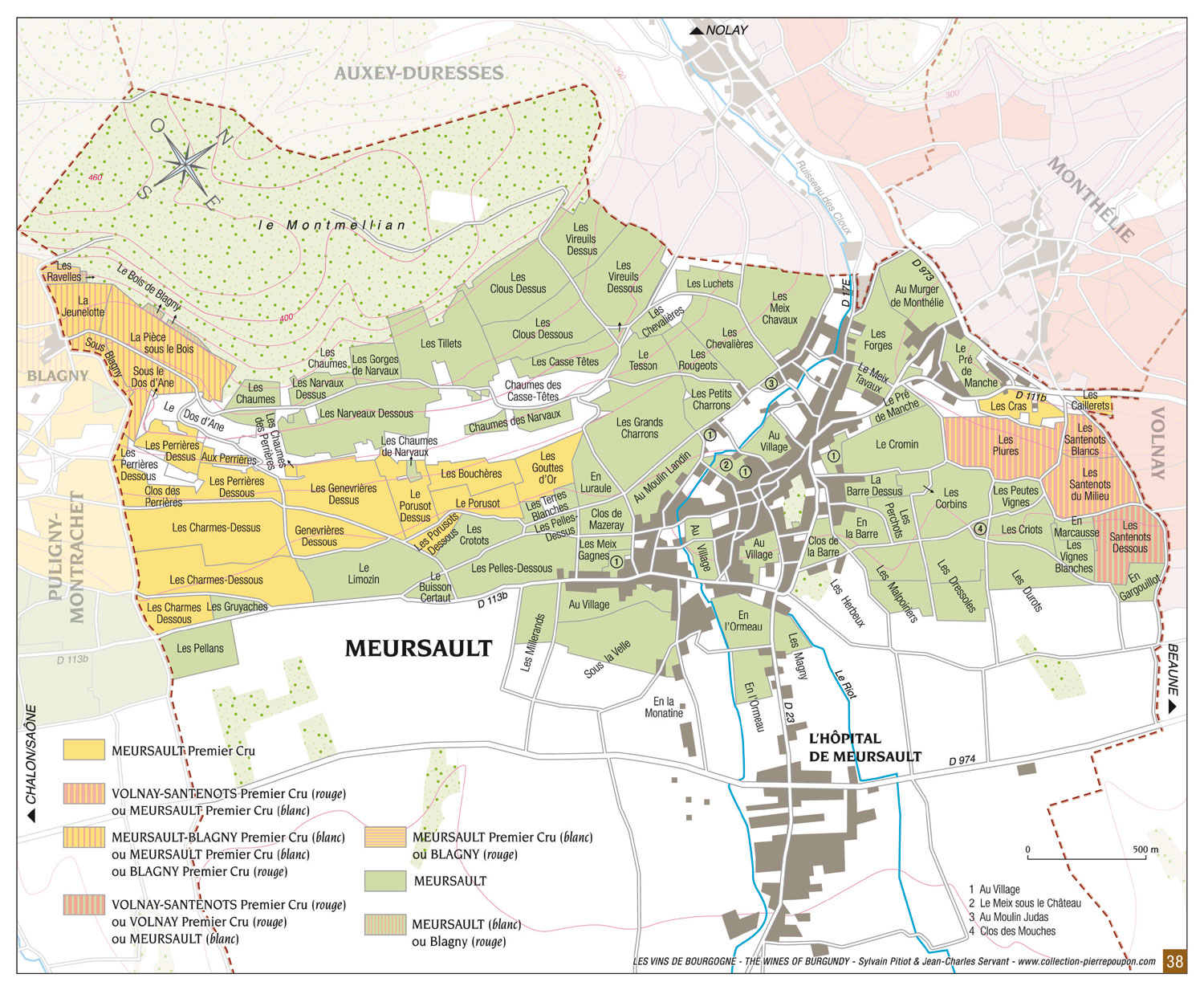

As it is traditional tasting in barrel rooms in the Côte d’Or, we finish with Chardonnay. Demougeot’s Meursault is composed from two different lieu-dit village sites, Les Pellans and Les Chaumes. Located low on the slope, Les Pellans sits just next to the Puligny-Montrachet border below the famous Meursault 1er Cru Charmes known for its full-bodied and burly shoulders. Planted in 1957, these old vines set on a deep clay topsoil bring weight, earthy power and thrust to this seemingly lithe, middleweight Meursault. Les Chaumes, planted in 1999 and just above a deep limestone quarry above the village’s most famous 1er Cru Les Perrières, is the pointed spear in the charge of this ensemble. The stony and shallow soils—just next to one of Coche-Dury’s principal sections that make up his Meursault—brings lift, high energy, tension and vibration. The combination of these two sites that sit above and below some of the most talented terroirs for white wine in all of Burgundy make this a noteworthy Meursault. As usual, everyone wants it but there’s so little to go around.

Planted in 1969 on just a tenth of a hectare (eight vine rows!), Rodolphe’s minuscule parcel of Meursault “Le Limozin” is surrounded by premier cru greatness on three sides. Indeed, not all village wines are created equal, and it’s good to note the location of this one: downslope from Genevrières, south of Les Porusots-Dessous, and north of Les Charmes-Dessous—not bad neighbors! Like his appellation Meursault, it’s another rare example—at least these days—of strikingly pure Meursault, devoid of overindulgent and trendy reductive winemaking notes. Its privileged placement among giants renders a deep body, dense interior and aromatic spring. The soils are deep with limestone-rich clay, and while this wine has striking tension, its depth is credited to its deep soils with a clear balance to bring weight, texture and finesse. The production is tiny with only five cases for the US.

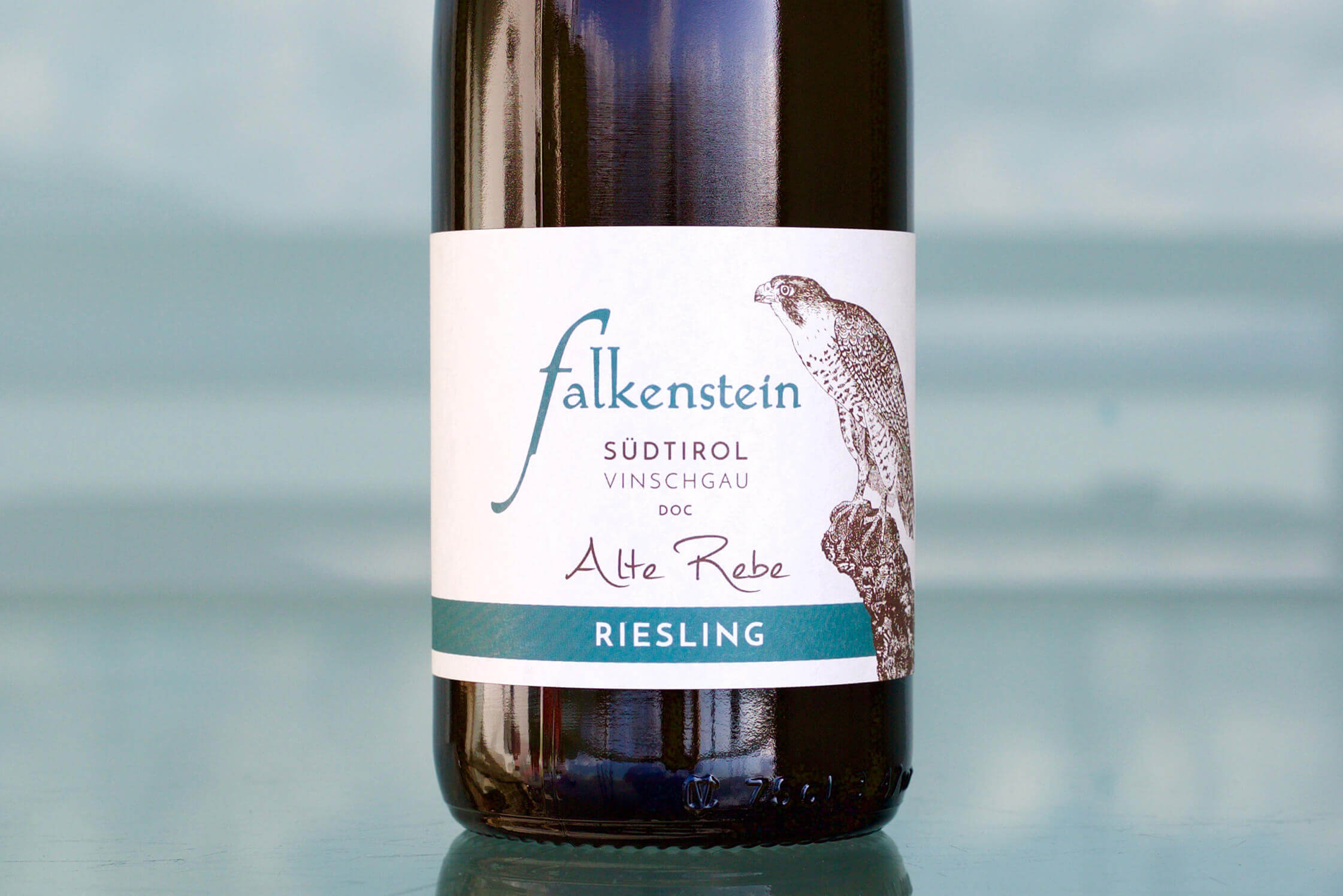

2021 is the vintage to understand just how good Falkenstein’s wines are. I tasted them out of vat with our Southern California team, JD Plotnick and Tyler Kavanaugh. Their eyebrows shot up like mine did a decade ago during my first encounter with their wines at a restaurant near Lago de Garda, with Le Fraghe’s Matilde Poggi. Our first vintages imported, 2019 and 2020, were warmer years. The wines were still exquisitely crafted by Franz Pratzner, the founder, owner and chief winegrower. Though more now under the welcome influence of his daughter, Magdalena, Franz was already doing great work before she returned from school and with experience from working in other wine regions. She’s gentle, but also a force of nature that will help elevate the level even more.

We tasted Falkenstein’s 2021s in their state-of-the-art, frigid cellar dug into the mountainside tricked-out with gorgeous medium-sized, mostly 10hl-18hl acacia botte in the middle of May 2022 with already sweltering heat that didn’t let up the rest of the year. If I ever had a cellar (and a lot of cash), it would look like theirs: immaculate and with big, beautiful, botte! When they released these vintages, we received our 2020s in California and needed time to work through them. They asked if we wanted to skip the 2021s and buy again with the release of the 2022s. Not a chance! The 2021s are too good and you need to know how special they are in the cooler years.

Grown on a mix of metamorphic and igneous bedrock, it shares similar geology to the region for Franz’s inspiration with Riesling, Austria’s Wachau, though from a different geological age. Franz’s wines speak the same language but with a different dialectic twist. The Südtirol’s Vinschau DOC is similarly continental/mountain climate with hot and dry summer days and frigid nights, though the Wachau has been much spottier as of late during fruit season with more frost and hail. While the Wachau is a narrow river gorge, the Vinschgau, or Val Venosta, is an expansive and steep-walled glacial valley. The topsoil of their vineyards are a mix of glacial moraine and sand derived from the bedrock. The vines are also at much higher altitudes than the Wachau, at 600-900m—about 400m maximum in the Wachau.

First up, the 2021 Weissburgunder. In Südtirol, Weissburgunder (more commonly known as Pinot Bianco or Pinot Blanc) is often considered the top white variety and when tasting those from the best local cellars, it’s easy to see why. On Jancis Robinson’s website, she describes the grape as it usually presents itself in most regions: “Useful rather than exciting.” She’s right. The majority are like that. But things are changing, and this grape offers pretty dull wines most of the time (especially further east in Friuli), but in Alpine country it thrives. Take Wasenhaus’ German Weissburgunders from Baden as another excellent example. In Südtirol, Weissburgunder is truly their top white, on average, and a lot more exciting than those produced elsewhere. Many whites grown in Südtirol grow well on the Dolomite limestone formations further east, and, just like the Sauvignon grown there, can be intensely racy, fully aromatic, and sharply textured. In the center of the broad region, on porphyry rock and glacial moraines, usually the hottest zones, they tend to be richer and more glycerol, salty, expressive of spices, honey, and more mature stone fruit. In the areas with the coldest nights and on more acidic soils, like those of Falkenstein, the combination of bedrock, sandy soil, bright sunny and warm days and frigid nights keep it fresh, lifted and complex. Weissburgunder is never a pushover inside special terroirs like Falkenstein’s. And 2021 is the season to give them a spin if you’re looking for more zing in your Pinot Blanc.

My wife thought Marrakech would be similar to Napoli, one of her favorite cities. But on Napoli’s most chaotic roads (which are everywhere), at least you have the body armor of a car. The center streets of Marrakech are narrow and dirtier, but not with the scattered and ubiquitous trash like Naples. Marrakech has a lot of dirt, brake dust, smoke, exhaust, buildings in ruins, quieter and gentler people, and cats … lots of cats.

After quickly rinsing off the air-travel grime and donning a fresh set of clothes, outside of the riad (a small privately owned hotel), wood and meat smoke, tajines, herbs, spices, and motorbike exhaust are instantly cured into your skin, hair, and clothes that were fresh a minute ago. Everyone is on their toes, even the locals, and tourists’ heads bob up and down as they check their spotty phone navigation apps trying to decide which street to take as men and boys honk and blister by them through the souk market on bikes. Among the disgusting and divine scents, I was happy that one was notably absent: that of dogs; their scent couldn’t be found anywhere. I don’t mean the smell of puppy fur only a couple days after a bath (which I and most people like), but rather the stink of Europe’s urban centers where dog owners all too often shirk responsibility for their animal’s messes (necesidades, as the Spanish say) and the noise pollution of territorial barking. I saw only one old black-and-tan canine trotting through the chaotic traffic at dinner time, tongue out, confident.

Though it’s a mere hour and forty minutes by plane from Porto, it’s a very different world. Despite warnings about dark streets at night and misdirection from locals with dubious intent, the only things I felt were unsafe were the bikes and cars. But for as much shock and terror as there was in realizing that there were only millimeters separating us from severe injury or death every thirty seconds, my wife was anxious and somehow relaxed at the same time. A change of activity and mindset was needed: no home and office habits, no computers, poor cell phone coverage (and I was disappointed my phone worked at all)—every reminder of our privileged life back home was gone. And on the street of Marrakech, your inner yogi has no choice: you must be present, or you’ll get run over.

The highlight of our trip was the day we spent in the Atlas Mountains with a Berber family. Our first stop was Asni, a town in the lower mountains and foothills, damaged by last year’s earthquake, the most severe in over a hundred years, responsible for the death of a few thousand people—a tremendous amount in proportion to these sparsely populated areas. Some who slept in their clay houses were crushed by truck-sized boulders crashing from above, and many survivors now live in tents outside of their ruins while they rebuild. We stopped at the Saturday market for the vegetables we needed for our cooking class with a Berber woman, Latifa, who taught us how to make the real-deal tajin, fresh bread and the unforgettable and easy-to-make eggplant dish, zaalouk. Without a doubt, I was the only blond, fair-skinned dude, and my wife was the only woman I saw among the mess of tents and rough-but-kind Berber men. And I’m sure there were positively no California health code violations in that market …

We barely made it back to the airport after three days. Not because we didn’t have enough time, but because our young driver was a stone-silent, horn-honking swerving, needle-threading, 4-Runner-driving madman with a death wish. Our lives were out of our hands for thirty minutes, but we got to where we were going.