Walking by the Santa Barbara Mission with my wife on an unseasonably cool day in the second week of July, she said, “The weather is strange this year.” Each year is unique, with 2024 being no exception, and people have said that every year as far back as I can remember.

So far it’s been cooler across most of Europe. Mildew pressure is a serious problem along with other issues, like hail. This year, many organic growers opted out of certification because to stay on their philosophical paths some regions would have risked a season with no crops. Given the extreme nature of this very wet and cold year, it’s best not to be too quick in judging those who put their ideals on hold and made this exception to save their businesses—some years are just too hard for certain places and it’s getting worse. And I would ask, would any of us give up three-quarters of our annual earnings out of principle when it would put our future at risk in these uncertain times?

The good news is that despite the challenges and losses of fruit, many have already said it reminded them of the cool 2021 season. Let’s hope for the same quality results! The scorch has yet to arrive.

Before I flew to the US for a couple of months to support my network in the market here, I drove through the south of France and into Beaujolais, then Jura, Côte d’Or, Champagne, and finally Chablis. My five-day schedule moved at a break-neck speed, which I prefer less and less these days as I like to take my time to let my visits digest (along with the foods few can resist) while taking proper care of this organism I’m trapped in.

My first visit was in Beaujolais, and if there were perfect wines to taste at 8:30 in the morning it would be the Dutraive family’s newly bottled 2023s. In 2022, they returned to form despite the nature of this bigger crop year with its bolder wines; they’re stout but still reflect Dutraive’s golden era. The 2023s take another step closer to the epic string of years crafted by Jean-Louis before the heat spell from 2017 to 2020. I had recently revisited the 2014 Dutraive wines with bottles from my cellar at the beginning of this trip and each was as good as I had hoped, with the highlights being Terroir Champagne, Le Clos, Brouilly, and La Part des Grives. I had a magnum of 2014 Clos de la Grand’Cour and it was very tight and needed hours before it fully opened up, though it should be noted that—at least in this vintage—they bottled the magnums by hand, so there is more variability than in the 750mls. I believe 2023 won’t be too far from that 12-12.5% alcohol vintage in style, only a little riper with most wines between 13-13.5%. The 2023s are lifted and fresh and showed very well during my tasting. They seem to have a leg up on the 2022s, as good as those are.

I have always requested they use at least some sulfites in their wines to help curb the potential of mousy characteristics, and the Dutraives have changed every recent cuvée from mostly no added sulfites to 10ppm (10mg/L). But mouse (strains of Lactobacillus and Pediococcus) in any wine with few or no added sulfites is a moving target: one day the wines are clear and the next day, they’re not. Sometimes the first hour is clean and beautiful until in the following hour the mouse scurries in.

If the tasting at the cellar is any indicator, 2023 should be an extremely successful vintage for the family. It was another warm year, but the wines are very elegant, lighter in color than 2022s, and brighter in fruit tone. I wanted to see how they showed ten hours after my initial tastes, so I started first thing in the morning and tasted again just before dinner. At the time, some had been in bottle for only a month and others for three months, but they didn’t change much in the ten hours from the first taste in the morning to my last of the day. I think we should prepare for some great stuff from Dutraive in 2023.

In the April 2024 Vinous Beaujolais article and review, “But Seriously: Beaujolais 2021-2023,” some of Anthony Thevenet’s wines were comfortably seated at the top of the review chart with a 94-point 2021 Morgon VV, and the highest confirmed mark (no range of score, like 94-96) of the entire review with his 95-point 2021 Morgon “Cuvée Centenaire.” I’ve said since the beginning that Anthony Thevenet will be considered one of Beaujolais’ best. He already is, and his powerful range of full-flavored Beaujolais was stunning and pristine. Anthony rarely uses more than 7mg/L of Total SO2, but somehow his wines have never in my experience been mousy. His 2022s are fabulous and the preview of 2023s is even more promising.

After Beaujolais it was a morning and afternoon in Jura visiting Nathalie and Sébastien Cartaux in L’Étoile, and their domaine, Cartaux-Bougaud. (There will be much more on this newly converted organic domaine whose wines are mostly raised in the historic 13th Century Château de Quintigny.) Theirs is a promising range with everything from bubbles to clean still wines of Pinot Noir, Poulsard, Trousseau, Chardonnay, Savagnin and, of course, wines under flor.

After Jura, we stopped in the Côte d’Or to visit David Duband and Rodolphe Demougeot. Rodolphe’s wines were on point, as usual. At David’s place, we tasted his normal range with his new no-added-sulfite collection called Les Terres de Phileandre. There are so many (too many!) excellent wines from David’s two ranges that I want to buy them all. 2022 and 2023 had bigger crops and there will be a flood of them out there. Only ten years ago, our warehouse was overfilled with numerous vintages from all our domaines, but these days they come in and then quickly disappear. Perhaps we’ll be able to have Burgundy in regular stock for the first time in years.

Next stop was directly north to Les Riceys to visit the now well-known superstar Élise Dechannes and her extraordinary Champagne micro-grower friend, Eric Collinet. The day of our meeting with Élise she was distraught as she was facing a rejection of her Rosé de Riceys by the tasting panel that approves the wines for the appellation. At that moment, they didn’t approve it and she was expected to “destroy” the entire lot. What a shock! I’m completely obsessed with her Rosé de Riceys and consider it my seventh wonder of the wine world. I’ve never had another rosé as good as the many bottles of Élise’s versions I’ve been lucky enough to have. I couldn’t understand why they would deny her appellation status. Too revolutionary? Too much energy? Too many naturally farmed grapes? Too good, I guess. Her Champagnes are equally stellar, and normally I like the simplest and most charming “Essentielle” the most. As I started to write this newsletter, I received the news that she challenged the verdict and got it reversed! So, we will have some 2022 Rosé de Riceys!

The Chablis wines of the still young (at heart, at least) Sébastien Christophe and the younger Romain Collet were as expected: Christophe’s a sort of marriage between Chablis and Loire Valley Chenin Blanc, and Collet’s styled somewhere between Chablis and Corton-Charlemagne. Their ranges were both fabulous, and we’ll get to those when they are on our shores. If the season doesn’t veer too far off its current path, 2024 Chablis might end up very similar to 2021. Fingers crossed.

The most thrilling visit on my tour was with the Richoux family, one of my spiritual/familial wine destinations in Europe. The Richoux family and all of us long-time fans were all worried about the 2018 and 2020 vintage wines that hit above 15% alcohol. Both of those years the phenolic ripeness was too far behind the sugar level, forcing them to wait longer to pick and then launch into a mad dash to get it all off at the same time—hard to do with more than twenty hand-harvested hectares. Some of the wines from these years were unrecognizable for this historically traditional grower whose wines were defined by strong structure, a tight fruit profile and lots of floral elements and freshness. Thierry has deliberately made their Irancy wines this way since the 1980s (also in the tradition of his father-in-law who owned the winery before). He also releases them closer to when they become more accessible to the average consumer, which often means four to seven years after the vintage date. Many of us who make up the Richoux fan club thought that maybe the appellation was irreversibly compromised by climate challenges; we wondered if it was the end of an era, but this visit put those worries to rest.

While the heat is changing the landscape from year to year, the magic of Irancy and Richoux is still there—perhaps it’s even greater. Gavin and Félix Richoux (Thierry’s sons) have had a lot of influence over the last ten years; their biggest change was organic certification (though they were already working organically) and biodynamic practices, no added sulfites until just before bottling, and more small format barrels (in this case, 500-600L instead of only one year in the large 55-80hl foudres and another one in stainless steel tanks) among other small adjustments. The wines are intended to take on more openness and lush fruit—a contrast to Thierry’s style, which often feels like classic cool climate Italian wines made in Burgundy. What’s on the horizon are the 2019s, which are richer than in the past but still fine and noble, a little Vosne-Romanée-like with its delicious, full red fruits, and the 2021s in the style of the southern end of Chambolle-Musigny: tighter, tenser, tucked-in but charming. Exciting!

It’s a volcanic island invasion at The Source! We love wines grown on all bedrock and soil types, particularly those grown in shallower topsoil with a notable root contact with the underlying bedrock. We work all over Europe and import wines of every imaginable geological type. Overall, igneous volcanic wines are about 8-10%, non-volcanic igneous (granites and such) about 12%, metamorphic bedrock 15%, and more than 60% on calcareous soils. We’d like to have a greater balance of bedrock types, but wines on calcareous soils somehow capture the regular wine consumer more than the others. Some limestone-heavy regions include the bulk of Tuscany, Barolo, Barbaresco, Central Loire Valley, Champagne, Côte d’Or, Chablis, Saint-Emilion, Provence, Rioja, Navarra, Ribera del Duero, y más.

Focusing on volcanic wines, we have Carlone’s hard rhyolitic ignimbrites in Boca; Fabio Zambolin’s deep and yellow volcanic sands in Costa della Sesia (unclassified Lessona DOC), Fliederhof’s St. Magdalener on porphyry, Madonna delle Grazie’s Basilicata Aglianicos on volcanic tuff and clay, and now a three-pack on Etna’s basalt with Federico Graziani, Etna Barrus, and a new producer for us in California, Azienda Agricola Sofia. In France, we have some Anjou vineyards of Patrick Boudouin on ancient volcanic rock that date back hundreds of millions of years to the last Pangea. And now in Spain, we have Carmelo Peña Santana’s Bien de Altura wines from the Canary Islands.

This spring, we took our maiden voyage to the Canary Islands to meet with Carmelo on his home island, Gran Canaria. It’s one of seven islands in a volcanic archipelago off the coast of Africa (directly west of southern Morocco and north of Western Sahara) created by what started as constant underwater eruptions that developed into islands from the continued tectonic separation along the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. Africa and South America broke apart and continue to move further away on the Atlantic side by about two to three centimeters per year. Gran Canaria is almost right in the center of the archipelago, between the two desert islands to the east, Fuerteventura and Lanzarote, and the islands to the west that become more tropical the further away from Africa they get, like Tenerife and Las Palmas.

On a topographical map of the islands, it’s easy to see that the southern side of each island is more desert-like and the northern part is greener, except Fuerteventura and Lanzarote, both deserts devoid of almost anything naturally green. Precipitation on each island is pretty sparse with (from east to west) Lazarote recording about 110mm (5.3 inches) per year; Fuerteventura 105mm (4.1 inches); Gran Canaria 134mm (5.3 inches), Tenerife, with a lot of variability depending on location, like the big spread between Santa Cruz de Tenerife at around 214mm (8.4 inches) and San Cristóbal de la Laguna at 557mm (21.9 inches); La Gomera 235mm (9.3 inches), El Hierro 170mm (6.7 inches), and finally, with the most rainfall and the greenest of the islands, La Palma with 324mm (12.8 inches). Generally, it’s not a lot. But because of the high altitude of some of the volcanoes, water is well-preserved on the northern exposures and also in good positions for viticulture in these desert/subtropical islands.

Temperature is also a major factor, and not surprisingly the altitude of each plays a major part. Among the main wine-producing islands, Tenerife has the highest peak by a big margin with Mount Teide hitting 3,718 meters (12,198 feet) with peak temperatures in the low 40s Celsius and the lowest recorded temps nearing -10°C. La Palma has the second highest peak with Roque de los Muchachos hitting 2,426m (7,959 feet) with the peak temps hitting the low 40s and the lowest at -3.7°C in January 2021. Gran Canaria is the third highest island with Pico de las Nieves (Snow Peak) hitting at 1,949 meters (6,394 feet) with peak temps in the mid-forties with the lowest also -3.7°C in January 2021 while Carmelo was pruning at around 1300m altitude. Lanzarote, the most desert-like viticultural island peaks at 671m (2,201 feet) at Peñas del Chache, with a high in the low mid-forties Celsius and its lowest recorded temperature of 8°C. All the islands with higher peaks will naturally have the lowest temperatures in certain spots during the winter.

Gran Canaria is a circular island with extreme desert on the south side and a pocket of tropical green (though still more desert than tropical) on the north side. Gran Canaria is not as famous for wine growing compared to Tenerife, but Carmelo is changing that.

Raised by his mother and grandmother, Juana and Lola, respectively, Carmelo inherited from them a big heart, warmth and charm, and the streets of Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, the inner-city energy and hustle of this island’s industrial port scrunched between the quiet volcano and Atlantic crammed with half a million locals and four million tourists each year into its one-hundred square kilometers (~38 square miles).

Carmelo returned home to Gran Canaria to begin Bien de Altura after traveling the world, including harvests in the southern hemisphere and a finish of his “practical” studies with the Portuguese wine luminary, Dirk Niepoort. At Niepoort, he befriended Dirk’s right-hand man, our very own Luis Candido da Silva, the toiler and mind behind Quinta da Carolina. It was also the beginning of El3mento, a project started by Luís and Carmelo which has now expanded to include close friends in Chile and Switzerland. Immediately Carmelo turned heads with his own-rooted vineyard wines that expressed the same bright and generous personality of their maker and the Listán Negro grape.

Listán Negro is the dominant grape on the island and in Carmelo’s wines. Listán Negro results in more elegant wines with a fresher fruit profile, while another famous Canary Islands grape, Listán Prieto (País), at least when compared to Listán Negro, produces a more robust, deeply complex, and fuller wine. (Side note: In Chile’s Itata Valley, País (Listán Prieto) grown on volcanic soil is much more elegant than those minerally and more rustic versions grown on Itata’s granitic soils.) The key to keeping both varieties aromatically pure and gentle on the palate is a vigilant tasting regimen during fermentation to prevent either variety from getting carried away on tannins and reduction before pressing, especially Prieto. However, under Carmelo’s watchful eye, the combination of the Canary Island varieties cofermented and untouched (unless necessary due to imposing reductive elements) during their month-long vinification before pressing usually does the trick. Without a clear idea of the cause, Carmelo often says that the volcanic wines produced in Gran Canaria are less expressive of reductive elements than those of Tenerife, the more famous island with loads of great producers and vines. Carmelo also makes a white from Listán Blanco, more commonly known in Spain as Palomino, but it rarely leaves the island.

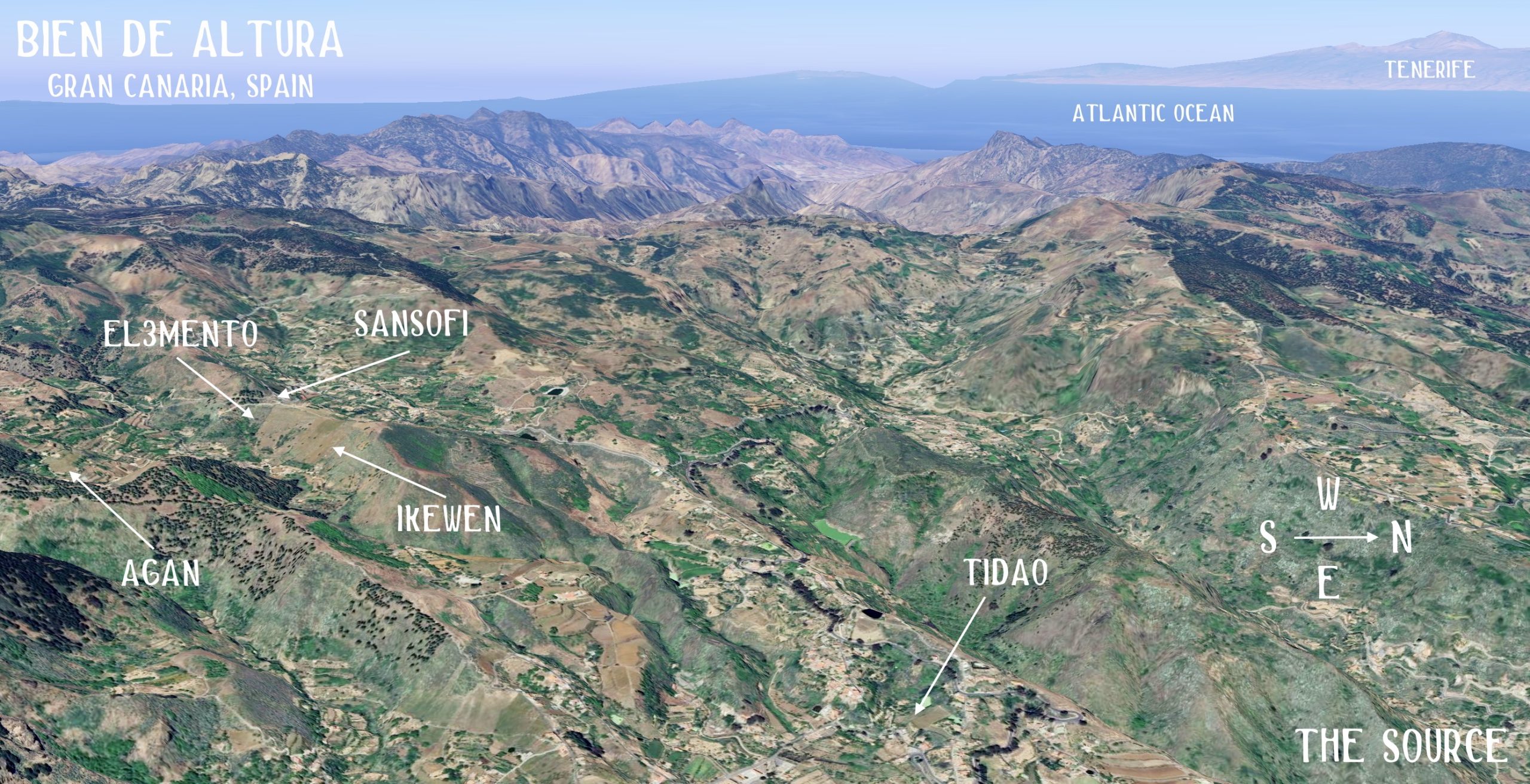

Carmelo focused his initial research on old vines in the higher altitude areas on the northeast side in the center area of the main volcanic cone, about four kilometers from the peak, Pico de las Nieves. Since he started in 2017, he’s amassed more vineyards and continues to seek out new parcels. Today, he makes five different red wines from the island, four from single-vineyard plots. Each parcel is, of course, on volcanic soil, and because there is no known phylloxera on any of the Canary Islands, every vine is own-rooted with what we would call, “indigenous” vines; perhaps “first-known generation” could be more suitable because there were no vines before the arrival of the Spaniards, who supposedly first arrived in the 15th Century after the conquest of the islands. There are historical documents, such as the writings of Pliny the Elder, that the Romans at least knew about the islands, though they may not have inhabited them. The timing of the Spanish invasion of today’s Islas Canarias also coincided with the exploration and settlement of the Americas, where they also planted vines around the same time, with Chile as another unique region (in this case, country!) suitable for quality viticulture void of phylloxera. Chile is also home to perhaps the world’s oldest living vines: País, the same as Listán Prieto.

(Interestingly, many Spaniards from Andalucía populated the Canary Islands whose descendants then populated Chile. This is probably why the Chilean accent and some cultural terms closely match the Canarios.)

Already an iconic label in the natural wine world’s rarities, Ikewen is a name bestowed in honor of the island’s Indigenous Berbers and/or Gaunches peoples, which in both languages means “origin.” Carmelo’s stable of vineyards continues to grow, and what was composed of three different vineyards only a few vintages ago is now taken from seven on the northeast side of the island (like all the parcels) with an average age of forty years with some over one hundred with own-rooted (pie franco, like all the vineyards) 85% Listán Negro (the elegant Listán) and 15% of other rare “first-known generation” varieties. The altitude ranges from 1,100-1,460 meters (3,600-4,800 feet) on mostly east-facing sites on extremely steep orange volcanic sand, silt, clay, and rocky topsoil.

While the single-parcel wines have distinctive personalities and go in a straight line, the parcel blend of Ikewen is the most universal. In smaller doses inside this vineyard ensemble, it hits the highest of the high tones and the lowest of the low tones in the entire range. The fruit profile meanders between pale red and slightly dark red, and its subtlety is supported by a more dynamic structure. All the wines are interesting and complex, but the combination of all seven parcels makes it particularly special. It’s by far his highest production wine but it may remain the most compelling simply because of its completeness and balance.

Once harvested, the whole-bunch fruit for Ikewen is fermented for five weeks in steel without any intended extractions: only a gentle pressing of the cap a dozen centimeters down by hand to keep it from building bacteria or volatile acidity in the upper and more exposed area of must/wine. After a gentle final pressing, it’s aged for a year in 85% steel and 15% in 225-500L old French oak and is neither fined nor filtered before bottling.

Three of the single-site wines, Tidao, Agan, and Sansofi, are all vinified for a five-week, whole-bunch fermentation/maceration in open-top 500L French oak barrels, followed by aging one year in 225-500L old French oak. Like Ikewen, they are neither fined nor filtered.

Often the most tantalizing and charming, sour red candy, red flower red in the range, Tidao comes from an own-rooted, 120-year-old single parcel (2024) on the northeast side of Gran Canaria planted with 70% Listán Negro and 30% of the reds, Tintilla, Listán Prieto (País) and Vijariego, and the whites Listán Blanco and Malvasia on a moderately steep undulating slope facing southeast at 1050-1070m on volcanic scree (breccia) bedrock with clay and silt topsoil. Important note: it’s a beauty and completely gulpable, so be careful with your company to ensure everyone is measured, and of the sharing type.

Agan, with its more solemn black and white label, is as compelling as any in Carmelo’s range. It’s often the most reserved upon opening, expressing more savory than sweet notes, with white pepper and delicate fruits that build with time. It’s a fine wine built on structure and subtlety and comes from a single parcel planted ninety years ago (2024) to 85% Listán Negro and 15% Listán Prieto, Listán Blanco & Malvasia on a medium-steep slope facing northeast at 1350-1370m. It’s just across the small ravine that separates the parcels for El3mento, Sansofi and a good portion of vines for Ikewen. Here, the volcanic bedrock is covered with loose, small volcanic rock (called picón), sand, clay, and silty red topsoil.

If Tidao is Carmelo’s ethereal charm, Agan his contemplation, Ikewen his balance, then Sansofi is his ideal; it has the best of each in his range found here but within a tighter framework. A ninety-year-old parcel (2024) planted to 85% Listán Negro and 15% Listán Prieto and Listán Blanco between the El3mento parcel and Ikewen vines on a medium-steep slope facing north at 1330-1365m on volcanic bedrock with picón, sand, clay, and silty red topsoil, this is the unique wine in the range that faces due north. Like Agan, Sansofi needs more time to open than Tidao and Ikewen—again, it’s best to share with fewer people.

Carmelo’s tribal wine, El3mento is also an outlier in style. Often led by bright floral notes and earth, it was aged for eight months in a 1000L amphora with the whole clusters, remaining unmoved with only the free-run wine kept for the final wine. It’s composed entirely of Listán Negro planted forty years ago (as of 2024) on an extremely steep slope adjacent to Sansofi but on the other side of the hill facing southeast (Sansofi, north). It shares the same volcanic picón, sand, clay, and silty red topsoil as the other wines, but with higher large volcanic rock content. El3mento is a project developed by Carmelo and Luís Candido da Silva, who met while at Niepoort in Portugal’s Douro Valley. Today, this project has extended to Switzerland and Chile’s Itata Valley, where these friends make their wines the same way, with long whole-cluster, post-fermentation macerations in amphora.