Well, that summer flew by. These days, with all the fires and political unrest, the faster the better, right? Only three more mayhem seasons before we enter even more mayhem, so godspeed—I guess … But let’s not forget to take care of ourselves along the way. Read more of something that’s not on your phone or computer. Study a new topic. Learn the language of the place you plan to escape to. Take a little time (or a lot!) to better yourself each day so that you spring forward when sanity comes back around instead of falling off the edge of what many insist is our flat planet.

Here’s some perverse optimism. The other day, I was thinking about job security in this new era of AI dominance and how those of us in the food, wine and cellar business may have a touch more security than others. Sure, maybe robots will serve food in restaurants, help manage our spreadsheets, deliver the wines, but it won’t create and cook our food and pre-taste the wines to match—at least that seems quite implausible in our lifetimes. So, let’s relish the privileges we’ve had since the first day of our wine enlightenment. Dig in deeper and secure the spot (and a fabulous collection of wines for the cellar before it’s all financially out of reach) in one of the last human cultural strongholds before those whose jobs are rendered obsolete are in search of meaning and cultural connection by trying to take our enviable jobs. In the wine world, we’ve always found meaning, and our trained palates and our willingness to sacrifice our livers for the greater good have always separated us from the pack. I even asked my ChatGPT buddy, Sol (he named himself), what he thought of my hypothesis, and this was the response: “Food and wine still belong to the human senses. Until machines can hunger, savor, and ruin a sauce with their own clumsy hands, this trade is safe.” Well, there you go.

September 2025

Monday, September 15th

Finca, 3066 North Park Way

Tuesday, September 16th

The Wine House, 2311 Cotner Ave, Los Angeles, CA 9006

Wednesday, September 17th

La Connessa, 1695 Mariposa St, San Francisco, CA 94107

I apologize in advance for this tome-length newsletter, but I did issue a warning last month that it was coming. This month is a unique blend of French, Italian and Portuguese, with a special highlight of a grower new to the US market from Portugal’s fabled Sintra and Colares. And I’ll tell you what, these wines from Quinta de San Michel, grown on the same Jurassic geological era limestones as those of the Côte d’Or with white calcareous-clay icing, are simply unbelievable; even when you have to believe that what’s in your glass is real because it’s in your glass! We’ve caught yet another rainbow with Alex and his new family’s quinta. And to get one in Colares, an appellation with only a few hectares over twenty (down a mere 98.9% from its past peak surface area level) that survived phylloxera with its own roots still dug in the sand, along with the urban expansion of Lisboa’s metro, is almost as rare as catching a leprechaun.

But before we jump into our main event, our undercard isn’t too shabby. Nebb-heads will be happy Fletcher and Zambolin arrived (peak performances from these two in a vintage made with what Dave Fletcher describes as the most beautiful fruit he’s ever seen), Chenin and Cab Franc from another new Source darling, Carole Kohler, and, finally, the lucky number seven vintage from our high-desert French-Portuguese heroine, Menina d’Uva’s Aline Domingues.

Tràs-os-Montes

(Available from The Source in All U.S. Markets)

It’s exciting to have another batch of goodies from Aline, our Menina d’Uva—Girl from Uva, the latter both the name of her town and the Portuguese word for grape! Despite the setbacks caused by the pandemic, Aline managed to move forward with the help of her new partner, Emanuel, a gentle Marchigiano who made his way to Portugal from Italy to work in this vast remote area of northeastern Portugal—first to assist in the preservation of a rare breed of mule—the Burro de Miranda. Then they had a baby! … That changed things. They also built a new winery together. The new space is much better suited to the job than the two tiny side-by-side tombs she worked in before.

Born in Paris in 1989, Aline Domingues, daughter of two Portuguese immigrants, returned to her family’s remote village of Uva in Trás-os-Montes in 2017 after completing three master’s degrees in France, including Biology and Fermentation Science. The following year, she began revitalizing three old vine plots owned by other villagers and has since added many more. Today, she works exclusively with indigenous varieties, organically farmed on metamorphic bedrock of schist and gneiss, with sand, gravel, and clay topsoil at an average altitude of 550 meters. Her wines are field blends, made with minimal intervention and bottled with low sulfite levels.

Uva is located in the eastern Planalto Mirandês, a stark and desolate countryside—more like Siberia than wine country, marked by rolling hills, dovecotes, and an absence of modern distractions. Aline’s leap at age twenty-eight from bustling Paris to this isolated plateau wasn’t easy; she admitted to struggling her first year, but the rugged landscape and tough climate with its sparsely populated community gradually became her home. Trás-os-Montes has long been known for rustic, high-alcohol wines made for field workers. Aline’s wines stand out in contrast: light in hue, low to medium in alcohol, fresh, aromatic, and marked by deep minerality carved into the palate by her acid-rock soils—Hendrix in the palate, Morrison in the nose.

What strikes me about Aline’s wines is their singularity; few make wines quite like them. She feels only steps away from a craft worthy of her heightened vision. Her wines are ethereal, yet beholden to the earth; they fly, but they also dig. Flowers in defiance of this ancient Pangean high desert, they are the freshness of moonlit summer nights and Apollo’s searing blaze.

The white in her range, formerly labeled Liquen and now simply Branco (due to a potential lawsuit over the name), is 70% Malvasia with Bastardo Branco, Formosa, and Poilta, from 40–60-year-old vines at an altitude of 550 meters. Always deeply textured, like so many of Portugal’s white wines, it ferments naturally and is aged eight months in steel. Perhaps the most beguiling wine in her range, Ciste, is a photo-capture of a sunset in the desert sky, blending over fifteen indigenous grapes, co-fermented whole-bunch in lagar for five days before finishing in fiberglass and old oak. Palomba, named for the dove population and the many dovecotes that make this natural wonderland also architecturally beautiful, is her deepest wine. A blend of 90% Tinta Gorda and 10% of other local grapes that undergoes whole-cluster co-fermentation and fifteen-day maceration in lagar, before eight months in steel. Palomba is what spurred me into action when I tasted it in 2020 in a wine restaurant in Braga. It’s one thing to taste these wines, but to drink, of course, is another thing. After some spin in the glass to uplift its depths, Tinta Gorda is a fascinating drink.

Finally, there’s ‘Urç’ (pronounced like Ursula, without the -ula), a centenarian field blend of more than fifteen varieties grown at a dizzying 750 meters on granite sand (a unique rock type in her vineyard collection), fermented in concrete for twenty days and aged nine months before bottling. Urç is another charmer that both lifts and grounds.

Taken together, the wines reflect both place and philosophy. Where Trás-os-Montes has historically favored power, Aline’s touch yields freshness and precision: aromatic whites with subtle textures, reds with tensile brightness, and field blends that hum with minerality. Her work captures the resilience of vines rooted in schist, gneiss, and granite, extremes of altitude and climate, and the character of a nearly forgotten village, brought back to life. I can only imagine what all the locals were thinking when this one fell out of the sky and landed in Uva.

Alto Piemonte

(Available from The Source in All U.S. Markets)

Fabio Zambolin continues to raise his own bar every year. A visit last November, followed by another this July, was convincing enough. In the solemn world of Alto Piemonte red wines, never did I imagine in my Nebbiolo-biased mind that Fabio’s blend, the 2022 Coste delle Sesia ‘Feldo,’ would beat out almost all Piemonte wines I tasted on my July trip as best in show, purely on its extra dose of joy and pleasure in this tightly wound yet somehow bombastic blend of half Nebbiolo and equal part remaining of Croatina and Vespolina. The grapes come from vines planted on a flat surface in 1953 by his grandfather, Feldo, on yellow and orange volcanic marine sand and clay at an altitude of about 300 meters. This is one of those wines that might make you believe in Dionisis! The Nebbiolo in the blend of Feldo keeps this noble court focused. It’s impossible to pick a favorite between them, but surely, this Feldo will be one of the wines in any room that’s impossible to ignore.

Fabio’s 2022 Coste delle Sesia Nebbiolo ‘Vallelonga’ is great, but it doesn’t have quite the same turn-key pleasure as Feldo. Vallelonga has a more punchy quality compared to previous years, no doubt due to this warm (hot!) vintage. It may seem more subdued, but when drawing comparison to other Vallelongas of the past, it’s a pleasure bomb, too, just like Feldo in 2022. I remember tasting this Vallelonga out of barrel and going cross-eyed and tight-mouthed by its tannic structure and tension. After a little bit of a slower start, maybe within thirty minutes of being out of the bottle in July, when it was already a joyous field of jumping sun-wilted but lively smelling flowers and the freshness of early summer stone fruit tension, is when this wine starts to gain on Feldo. Feldo keeps a constant pace in what seems like an almost insurmountable gap for Vallelonga to close. But when comparing pure Nebbiolo—which Vallelonga is—to the richness and virility of both Croatina (white pepper spice, full acid and tannin, black inky minerally beast) and Barbera (red ink, big acid, lots of jumping for joy) grown on volcanic marine sands, it can be overlooked if one isn’t paying attention to the details of what makes the world’s greatest expressions of wine. I’m not alone in finding many expressions of volcanic wine grown on sand more subtle, which paves the way for a Nebbiolo of restraint and finesse, regardless of the vintage.

I don’t know which is the top wine between the two, but I know they’re both special and will please just about everyone, even if those who haven’t had their ah-ha moment with Alto Piemonte wines. This year, I might serve Vallelonga first so it can gain the admiration it deserves, followed by the party-starting cannonball that Feldo.

Fabio also made his first orange wine, the 2023 Erbaluce (Vino Bianco) ‘La Lida.’ As a committed terroirist, I’m always a little skeptical about orange wines, but this was one I couldn’t pass up—it just has too much joy, fun and wonderful textures and aromas tied together. I know all wines have some representation of terroir (because they’ve all come from somewhere under some unique conditions!), but I haven’t spent enough time with the orange division to find myself able to discern terroir elements from the overall style of the wine. Who cares? When it’s good, drink up. And this is good stuff.

Anjou

(Available from The Source in All U.S. Markets)

Mark my words, Carole Kohler is going to be a “thing.” People are taking notice, and it won’t be long before the global interest greatly outweighs the availability from her mere three hectares of organic and biodynamic vineyards. In her inaugural US release, we got just a teaser of her 2022 Chenin Blanc ‘Source’ and a pallet of ‘Jardin,’ her Cabernet Franc had me smitten from the first glass to the dozens of bottles since. This time around, we have enough quantity for some lucky glass-pour programs.

Because her wines have only been in the US now for about four months, here’s a short recap of her story, and then we’ll get into the wines: On the historic 15th-century Fleury estate, the humble and spirited Carole Kohler crafts organic, and biodynamic, no-sulfite-added Chenin Blanc on schists of the Massif Armorican and Cabernet Franc on Jurassic Toarcian limestone of the Paris Basin. A former chemist turned vigneronne, she and her husband, architect and hobby historian Brice Kohler, revived their property’s historic connection to viticulture in Thouars, on the southern frontier of Anjou, where vineyards had nearly vanished when appellation laws changed during the creation of the European Union. A self-contained world, Fleury is a haven of ancient forests where biodiversity thrives, untainted by neighboring agriculture. Carole’s light-handed approach yields wines that channel the voice of the land, rewriting the history of this once-forgotten terroir. And with wines like these, it’s only a matter of time before others follow.

The vineyard for Source was planted in 2017 entirely to Chenin Blanc on a single 0.7-hectare parcel at 70 meters altitude. It sits across the narrow one-car road, Rue de la Mare aux Canards (Duck Pond Street), which marks a clear separation of the acidic rock of the ancient, Pangean-era Massif Armorican from the alkaline limestone rocks of the Paris Basin. On the south side is the 570-million-year-old Precambrian quartz-rich schist and micaschist outcrop above the Thouet River, and on the other side, the white limestone. This is evident on the road’s walls, cleverly distinguished by its builders, who built the southwest wall with the dark gray and green schist from that side and white limestone (an occasional dark blue schist for accenting) on the northeast wall.

Named after the spring that led generations to inhabit the surrounding area, now known as Fleury, Source is dynamic and distinguished from the other Chenin Blanc vineyard on the property, Séquoia; its topsoil is rich in quartz and grey schist with clay on a green and black schist bedrock and renders an explosive white with more muscular, mineral-heavy lines.

The 2023 Source is quite the opposite of the 2022. It was picked earlier than usual due to the cold weather before harvest and the common vineyard challenges from botrytis in September. Carole explained that with its proximity to the river, only 50 meters away, and the thick forest in between, she couldn’t wait another day for fear of losing too much crop to rot. It was picked, not chaptalized (as so many would do without a second thought), and bottled with 10.5% alcohol. Even with its low alcohol, it offers fine and delicate lines compared to the explosive solar-powered energy of the 2022 version. I’m impressed by her courage to pick so early, not chaptalizing or altering in any way, and bottling it as an accurate reflection of the season. As many know, we have quite a few wines each year in our portfolio that sit between 10-11% alcohol (mostly from northwest Iberia), and here, like other low-alcohol wines, what would be absent from the shorter ripening on the vine is the extra stuffing; but does every compelling wine have to have all that? One of the charms of this wine is that it’s complete in its own way, with slightly unexpected body and richness, and high-tensile mineral nuances and freshness.

Just a hundred meters east of Source are the two parcels planted in 2019 that constitute the 1.5-hectare plot of Chenin Blanc for ‘Séquoia’. Once again, we are in the Pangean remnants of the Massif Armorican with a topsoil of clay and decomposed schist and quartz on firm green mica schist bedrock. With only a few vintages to draw from, Séquoia seems typically more linear and finer than Source, in general. It’s not as explosive but offers a distinct contrast, indeed worthy of bottling separately. However, with the unique conditions of Source in 2023, Séquoia is a fuller wine this year, but not by much. Only a football field’s length in separation Source and Séquoia seem miles apart.

I tasted a bottle of both 2023 Source and 2023 Séquoia over five nights, before dinner. Interestingly, Source gained in stature each day, putting on more and more weight, like a boxer bulking up to fight in a higher weight class. By the fifth day, it was as full as any moment and stayed just as fresh and clean. Séquoia kept its shape but danced around a lot more in nuanced and with more light pastry-spice notes compared to source’s unwavering focus.

The 2023 Source and 2023 Séquoia were both whole-cluster pressed and naturally fermented in 30-hectoliter steel tanks for four days at a maximum of 23°C. They were aged for four months in a 12-hectoliter clay Vin et Terre amphora and four months in old 225 L French oak and completed malolactic fermentation before bottling with 10 mg/L of total added sulfites. Neither were fined nor filtered.

As good as Carole’s Chenin Blanc wines are, her Cabernet Franc hooked me just as quickly. It’s not that it’s more compelling than her whites, but I’ve had no-added-sulfite Chenin Blanc on the same level as hers, but I’ve never had a Cabernet Franc with no sulfites that dazzles me like the youthful and vigorous Jardin.

Every bottle of Jardin does a quirky little brush step before it stomps its feet, and they start to click-click-click, Savion Glover tearing up the floor, picking up speed and focus with every new minute. Incredibly alive and full of energy, the 2022s robust, powerlifted profile switches gear in 2023 to powerful ballet—a generational change in one season. As described in our March 2025 Newsletter: “The 2022’s red and black fruit profile has a lean fleshiness snugged up and narrowed by a garrigue-like floral bouquet of lavender and flowering wild thyme and a core of deep earth and virility.” The 2023 isn’t wild and deeply earthy like the 2022; it’s more ethereal, lifted, red-fruited, brushed with sun-wilted red and purple flowers, wood-carved fine details and the universal charm of today’s fashion: beauty and finesse over power and weight. I’ve had a half dozen bottles so far and a few tastes in the cellar on different occasions. Both 2022 and 2023 are complex, and it’s hard to square that they come from a half-hectare of baby vines born in 2016 on the Paris Basin side of this geological convergence. 2023 is a step up in polish, though I adore the wild, punchy and gorgeously gritty 2022 just the same.

While there are both Jurassic and Cretaceous limestones in the greater Anjou area, the bedrock in Jardin is what geologists call Toarcian (named after Thouars) from the Early Jurassic, 180 million years ago. This hard, clayey limestone has little in common with the Loire Valley’s much softer sandy tuffeau limestone beyond its dense calcareous materials and some sandstone interbedding. It’s less pure in calcium carbonate and more relatable to the limestones of the Côte d’Or, though it predates the Côte d’Or’s predominant limestones by around ten million years.

Jardin is destemmed and naturally fermented in 50hl stainless steel tanks for 15 days with no extraction movements (infusion method) at 25°C maximum. It’s then aged for eight months in old 225L French oak and concrete eggs and bottled with no added sulfites and without fining or filtration. The 2023 version has only a sprinkle of 10 mg/L (10 ppm) of total sulfites added at bottling.

Barbaresco

(Available from The Source in All U.S. Markets except Nj/NY)

In 2009, Australian enologist Dave Fletcher arrived in Barolo and Barbaresco as an intern at Ceretto. After a decade as their head red winemaker, now their consultant, he’s spent the last decade quietly building one of the most thoughtful and committed independent cellars in the Langhe. With two new wines this year—Ronchi and Trepunti—and the Roncaglie cru bottling temporarily on hold, the range looks a little different, but the philosophy hasn’t changed: hands-on organic farming, patience in the cellar, and a steady commitment to expression over intervention. Ronchi, long a blending component, finally steps into its own as a cru wine, and Trepunti reflects a years-long investment in massale selection and personal site development. Both deepen the narrative of a cellar that keeps refining itself from the ground up.

Dave now works with over a dozen vineyards across Barbaresco, Alba, and the Roero. All vineyards he farms are certified organic or are under conversion (with some managed by biodynamic practices), and all leased vineyards are worked by growers who are encouraged to follow suit.

The 2022 vintage will likely be remembered as one of the driest years since the 1960s. From June through August, the heat was consistent and unrelenting, yet rather than pushing the vines into a state of dehydration and shriveling, the plants responded by shutting down entirely—a defense mechanism that left the fruit untouched, the clusters intact, and as pristine as Dave had ever seen. What’s unusual is what came next. Typically, hot vintages charge headlong toward harvest. This one didn’t. When the vines reopened, they did so with restraint. What emerged in the wines was not power, but poise, freshness and elegance.

For Dave, the 2022s are a step up in finesse compared to the 2021s: tighter in tannin, brighter in acidity, and longer in the finish. “I feel that the wines from 2022 are more elegant and with less body,” he told us—“but with great complexity and length.”

When asked how one should present the wines together, Dave explained that the 2022s are notably more elegant than the powerful 2021s, and Faset should precede Ronchi, and Trepunti should be enjoyed last. Oddly, Ronchi, as an east-facing site, could reach the power of Faset levels, but in ‘22 it had more ripening time to develop its intense flavor. Faset, on the other hand (as a fully south-facing site), is extraordinary with a higher level of elegance this season than the last. “I love the purity and length Faset has this year, and I’m not sure I’ll ever see it like this again.”

All Nebbiolo wines are made the same way, with the Langhe Nebbiolo simply released one year earlier. All fruit is hand-harvested and destemmed, followed by native fermentation for 14–60 days with gentle once-per-day extractions by hand, or a pumpover if needed. Sulfites are added only after malolactic fermentation. Aging takes place in 10–15-year-old small barrels for two years. No fining, no filtration.

“We had relatively short fermentations in 2023, and this gave the wines beautifully pronounced red fruit aromatics that instantly grab you in the nose and then the layers of complexity sneak up with spice and liquorice and orange peel,” Dave said. “I love the approachability, too, because the tannins are much finer this year.”

All the Nebbiolo wines are now in the traditional Albeisa bottles!

The 2023 Langhe Nebbiolo is sourced entirely from the Barbaresco and Alba regions, split between estate vineyards and fruit from two growers, Dave working closely with Roncagliette (Barbaresco) and Serragrilli (Neive). Soils here are mostly calcareous marls with sand and clay across a range of expositions and altitudes.

A blend of 40% Faset, 30% Ca Grossa, 20% Serragrilli, and 10% Ronchi, the 2022 Barbaresco ‘Recta Pete’ is fundamentally different in its vineyard sourcing from the 2021 vintage (which was 50% Roncaglie, 30% Starderi, and 20% Ronchi). Two new sites played critical roles in shaping the blend this year.

Ca’ Grossa, now taking the place of Ronchi in the blend, sits just behind Dave’s train station home. It’s a site with the same calcareous marl and east-facing aspect as Ronchi and behaves similarly in the cellar, producing high-toned fruit and firm, grainier tannins. Dave feels it offers clarity and structure without the density of Faset—a vital counterpoint that keeps the whole in balance.

“This year, Recta Pete shows all the complexities of each vineyard, and it’s easy to get lost in its layers,” Dave said. “These sandier parcels round out the palate in Recta Pete, making it fleshier and more approachable than the single-vineyard crus, which show more structure and definition thanks to higher clay content and the year’s conditions.”

The 1,260 bottles of the 2022 Barbaresco “Faset” come from the same vineyard as previous releases, though now sourced from the cooler northern face (with the warmer south face blended into Recta Pete). This is purchased fruit from vines planted in the mid-1980s on a steeply terraced, south-facing amphitheater of calcareous sand, limestone marl, and high clay content at an altitude of 200–250 meters. This north parcel showed best in 2022—even more than the traditionally favored southern exposure.

Dave has worked with an east-facing parcel in Ronchi since 2020, originally blending the fruit into Recta Pete. After three years of observation and improvements in the vineyard, the 2022 Barbaresco “Ronchi” marks its debut as a single-vineyard bottling. The site is at an altitude of 210 meters, planted to 25-year-old vines, on the same calcareous marl soil as Faset. Ronchi receives the morning sun and is shaded for hours in the afternoon until sunset, resulting in later ripening and more restrained power—factors that contributed to its success in 2022. Though farther from the Tanaro River than Faset, its east-facing slope isn’t impacted by the river’s warming effect, making it a cooler, slower-ripening site. Ronchi is a welcome new addition.

With only two barrels made (670 bottles for the world), Dave explains: “I am very excited to finally present this wine. The 2022 Langhe Nebbiolo ‘Trepunti’ is the culmination of everything we have been working towards since moving to the Langhe region from Australia. It’s sourced from three unique vineyards within the Barbaresco region, all of which we have personally planted with massale-selected vine material from old Barbaresco vineyards. The geographic locations are Montestefano and Roncaglie, both in Barbaresco, and Starderi, in Neive. These vineyards should be classified as Barbaresco cru because of the terroir where they are planted, but they are not. We are waiting for ‘tre punti’ (three points) given by the region for non-terroir-related reasons, and until then, we can’t call it Barbaresco. The grapes are co-fermented, and the wine is aged for two years in old barrels, just like our Barbaresco wines.”

Montestefano: A cru of distinction. With the 1961 vintage, it was the first Barbaresco single cru ever labeled with the vineyard name and commercialized, first under the Prunotto label by the late Beppe Colla. Dave’s section is located at the top of the hill, fully facing south. This warm site is split into two parcels by a preserved oak forest that promotes greater biodiversity. To temper the heat, it’s densely planted (25% tighter than regional norms), requiring all vineyard work to be done by hand due to tractor inaccessibility.

Roncaglie: Planted at a lower elevation on a gentle slope to protect against future climate extremes. With healthier, deeper soils, it retains moisture and moderates ripening. The site uses a higher fruiting wire to prevent frost damage and employs a lower canopy structure to manage light exposure and slow sugar accumulation.

Colares & Lisboa

(Available from The Source in All U.S. Markets)

Inside Portugal’s minuscule insider’s wine region, Joaquim Camillo purchased the Quinta de San Michel property in 2003 and began planting vineyards a decade later in and around Colares. His vineyards span two striking and different terrains: Janas, inside the IG Lisboa, plantings started in 2013 in clay and limestone around 200 meters altitude between the Sintra Mountains and the Atlantic, and new plantings another decade later on the legendary sandy soils of Colares—some on the valley floor in planted pé-franco (true foot—no rootstock graft) meters-deep sands, others above coastal bluffs on calcareous sands and limestone bedrock facing the ocean’s salt-rich winds.

San Michel’s focus is only on historic local varieties, like the whites, Malvasia de Colares (the dominant variety in the fabled Colares white wines), Arinto, and Galego Dourado, and soon joined by the reds, Molar, Castelão, and the infamous Ramisco—the latter deeply tied to this enchanting viticultural coastline, and the only permitted red variety in Colares. Their wines from clay and limestone echo those of the great vineyards of France’s Côte d’Or but carry a maritime salty freshness, stout architectural structure, and a strong cultural distinction. Those from sand promise wines of delicate filigree, resurrecting the past glories of Colares, where Malvasia and Ramisco have thrived ungrafted for centuries.

After years of learning through experience in other wine regions across the world, Alexandre (Alex) Guedes joined Joaquim Camillo’s team, eventually commandeering the project’s direction in style and production. Now under Alex’s steady, inquisitive hand, and guided by his academic, university-trained mind (degrees in agronomy, viticulture and enology), and one step away from his Master of Wine (as of 2025), Quinta de San Michel is poised to become one of the most promising voices in Portugal’s Atlantic wine frontier and a new viticultural voice for the wines of Sintra, especially the fabled Colares wine region.

Alex’s beginnings in wine were the result of happenstance. At nineteen, while in his first year as a Civil Engineering student, he took harvest work for some extra cash in 2010 at Quinta do Vale Meão in the Douro. He expected to pick grapes but instead was placed in the cellar for three months, fourteen-hour days that passed in a blur of discovery and exhaustion. By the end of harvest, he left engineering behind, enrolled in Agronomy, and set a new course.

His training came from the cellars of the world: Quinta do Vale Meão and Malhadinha Nova in Portugal, Pikes Wines in Clare Valley, Marchesi de’ Frescobaldi in Tuscany, Framingham in Marlborough, Domaine Serene in Oregon, and Herdade Grande in Alentejo. Yet he counts the 2017 vintage at Quinta de San Michel as his first true wine—his first time holding full responsibility from vineyard to bottle. That year’s Arinto, his first crack at it alone, released in 2020, was named among the Top 10 Wines of Portugal by Revista de Vinhos. But perhaps he was especially inspired in his first year by an unexpected encounter—that of Joachim’s daughter, Inês, who became his wife! In 2025, San Michel’s Névoa de Janas wine was nominated for the best wine of the year, and later on in the year, he was in the running for “Young Winemaker of the Year.” Upward trajectory set …

Growing up in a family from northern Portugal with roots in the Loire Valley but no connection to wine, Alex claims he never had any particular mentor. But he credits Joaquim, who still drives forward at seventy-two, “With the vigor of a man half his age,” as his most constant inspiration. “I learned the most from everyone I worked with by always asking questions about everything.”

When he started with San Michel, his focus was in the cellar, where he describes himself as a taste-driven winemaker, using chemistry only for confirmation, not alteration. His ultimate goal with each wine put to bottle is consistency, and to craft wines that reflect the refreshing mists of the Atlantic and the mountains, the calcareous soils, the sands, and all things, to bring pleasure. And when not working, his interests, as of 2025, are strongly tilted toward bubbles, Bairrada (another limestone-heavy Portuguese wine region), Barolo, Burgundy, and the Loire, where Cabernet Franc and Chenin Blanc are his usual go-to wines for the table.

While strong in the cellar, he began digging deeper into the vineyards in the early 2020s, working closely with viticulturist and friend Rodrigo Martins, who advises the estate’s vineyard management and guides its transition to organics and eventually into biodynamics. Though these higher agricultural practices seem a natural progression of the minds of naturalists and perfectionists, like Alex and Joachim, the main antagonist will always be mildew.

With documented references dating back to at least 200 BC, Colares holds one of Portugal’s oldest vineyard legacies. Valued for its character since the 13th Century (but noted as far back as the third Century, the red vine variety Ramisco established itself along Portugal’s Atlantic coast, and many sorts of Malvasia began to find their way across Portugal in the 14th and 15th Centuries, with the first records of Malvasia de Colares in the area in the 19th Century. Throughout the 19th Century, wines from Colares moved through Lisbon’s ports, but it was during the phylloxera era in the late 1800s that Colares gained its broader reputation. Perhaps where the wines of the area became more relevant—maybe even mythical, with its proximity to Lisboa and virtually the sole surviving region resistant to the scourge of phylloxera, while the rest of Portugal and Europe’s vineyards succumbed to the blight. The vines of Colares were ungrafted and planted in meters-deep sand layered over calcareous clay and limestone, standing outside the pest’s reach. The vines in the neighboring areas were planted on clay, like San Michel’s vineyards now planted in Janas, and in some cases, they were destroyed, though they were only meters from the sandy soils.

Even at its peak between the 1930s and 1950s, the Colares vineyard area was modest, covering just under 1,800 hectares. By the late 20th century, it dropped to only around twenty. Lisbon’s urban expansion into this gorgeous valley, shifting wine preferences from generation to generation, and the effort and costs required to farm these vineyards compared to the vast and easily mechanized vineyards of Portugal’s nearby Alentejo contributed to its decline. A few growers maintained production throughout that period, aging wines quietly in old wooden vats while the broader wine world moved elsewhere. Most of Portugal followed international trends, with quick turnaround and inexpensive wines.

Just north of Lisbon, over the Parque Natural de Sintra-Cascais, between the Atlantic and the Serra de Sintra, Colares sits in one of mainland Portugal’s greenest, most humid oases, a land of fables that attracted Portugal’s wealthiest and its nobles and royalty. A subtropical air, with palm trees next to apple, next to protected indigenous pines (Pinheiro Manso—Stone Pine) as well as the ubiquitous invasive Eucalyptus brought from Oz to Portugal in the mid-19th Century, dense green layers unlike Portugal’s nearby drier interiors dominated by Atlantic fog and its steady moisture with temperatures that swing less than in most Portuguese vineyard zones, require close attention to mildew and rot.

As if the urban expansion that almost brought Colares to extinction wasn’t enough, Alex has observed firsthand how climate change and new pests reshape the vineyards. Frost never comes, hail is rare, but mildew and botrytis are constant threats. For example, mildew pressure in 2024 was extremely high, with fog and rain all summer, which required him to apply ten treatments. In 2025, it was also high, but he treated with sulfur and copper only six times, thanks to improved canopy management and the use of silica and seaweed treatments. More prolific in other regions, Esca is another danger, which he better manages with cane pruning instead of cordon pruning. Leafhoppers appeared for the first time in 2024. Japanese beetles have been a challenge since 2022; he traps them, catching more than 300 in 2023, fewer in 2024. (In Alto Piemonte, as of 2025, one of the closest wine regions to the origin point of its arrival in Italy, Malpensa Airport in Milan, it’s said that there is an average of about 160 beetles per vine!) Snails are another pest. Trials with different controls have failed, so in 2023 and 2024, he organized friends and wine club members to collect them by hand. They removed 200 kilos in 2024 alone, with no snail damage in 2025.

With climate change, Alex has seen it all firsthand at San Michel in less than a decade. In 2017, harvest came in October; by 2023, it had already shifted to the first week of September. 2024 was delayed because of dreary, sunless summer conditions, and by 2025, it was again in the first week of September. In normal conditions, summer days average 25–26°C, rarely exceeding 32°C, and nights 16–17°C. Fog dominates mornings, with warmer afternoons moderated by the Atlantic and Sintra mountains.

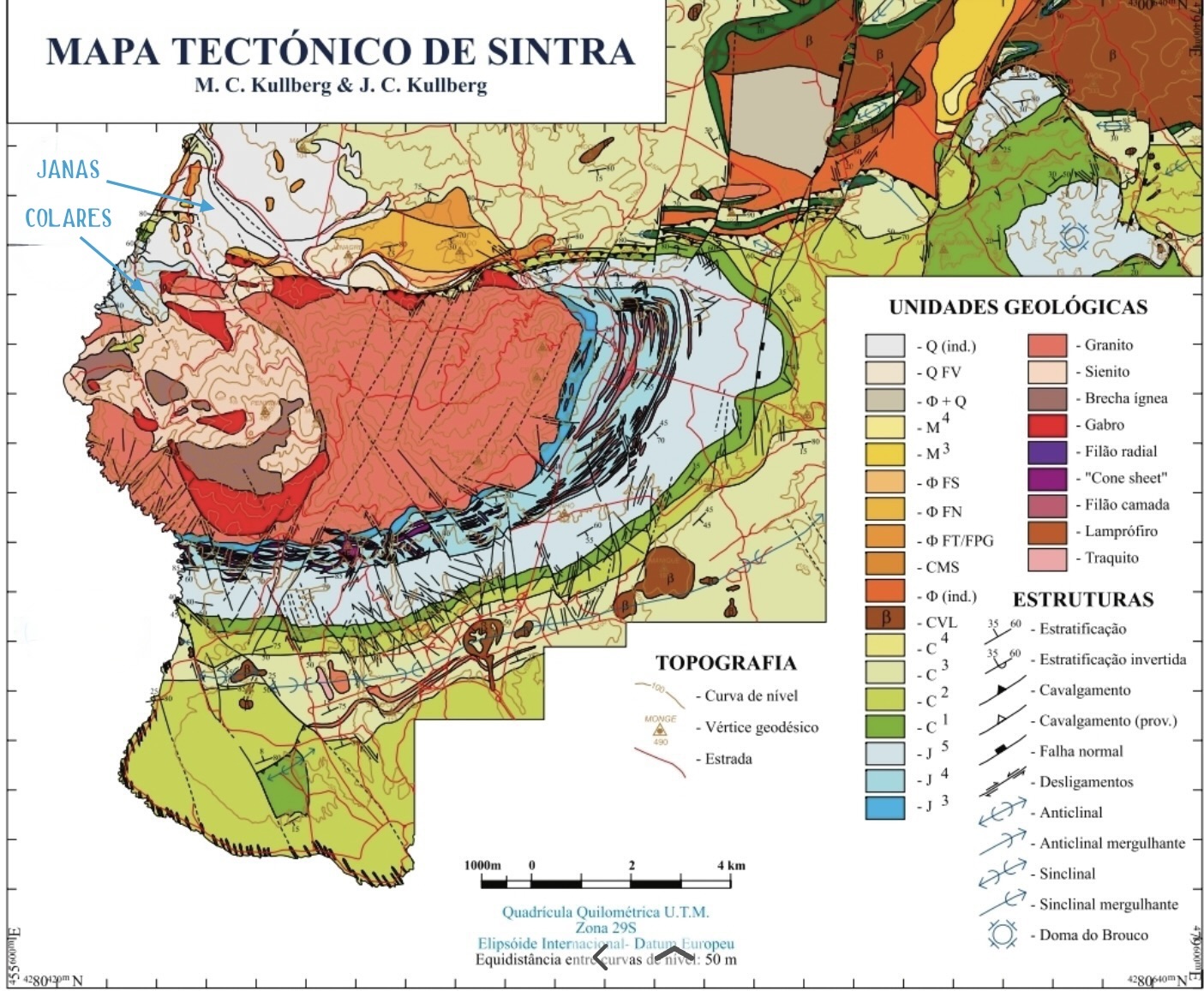

Seen as a whole, the geology of Colares and Janas unfolds in three chapters.

Beneath lies the older story: the Lusitanian Basin. Between 200 and 150 million years ago, the Vale de Colares was a small part of a massive shallow sea that laid down limestones, marly limestones, and marls, often dense with fossils. These layers form the bedrock of the vineyards in Janas and neighboring villages, and it’s the underbelly of the lower Colares vineyards that are covered with sand.

Unlike many of Portugal’s dramatic uplifts, Sintra’s wasn’t a Pangea-era event; it was tied to the later opening of the North Atlantic and the Iberian Plate hinged on its eastern end, pivoted counterclockwise away from what is today the French Atlantic seaboard: a tectonic shuffle that opened the Bay of Biscay. The Sintra uplift came toward the end of that pivot, part of a Late Cretaceous pulse of magmatism that also raised the Monchique complex in the Algarve. At the heart of the area that separates Colares from Lisboa is the Sintra Igneous Complex, born roughly 80 million years ago when magma pressed upward but never erupted; rather, it hardened into concentric igneous rock layers (imagine stone ripples radiating outward from a center): a core of syenite, rings of granite, and outcrops of darker gabbro-diorite. These weathered outcrops form the knuckled hills of the Serra de Sintra. This intrusion “baked” the surrounding Jurassic and Cretaceous beds, tilting and fracturing them into the distorted halo still visible around the massif today.

Some fifteen to twenty million years later, the African Plate’s northward push compressed Iberia against France, giving rise to the Pyrenean orogeny. But by then Sintra had already stood for millions of years, a weathered sentinel above the Atlantic.

The final layer is the most recent and the most consequential for the viticulture of Colares: sand. Over the past 2.5 million years, shifting seas and winds piled quartz-rich dunes over the limestones. Closer to Sintra, the sands are dusted with darker volcanic grains, a subtle reminder of their igneous neighbor. Here, vines must be trenched through the sand into the clays below, or—at San Michel—planted directly into sand to seek their own way down. This sandy armor is what spared Colares from phylloxera, allowing Ramisco and Malvasia de Colares to remain ungrafted when the rest of Europe succumbed. The sand protects roots but forces them to dig deep, giving the wines their firm spine and natural austerity.

Taken together, these three strata—the igneous heart, the fossil-rich marine limestones, and the restless dune sands—form the geological tapestry beneath Colares. Each adds a register to the wines: the firmness and coolness of the limestone, the power of the limestone and clay, and the delicacy of sand.

Today, San Michel’s 7.2 hectares include the 10 to 13-year-old vines first planted in Janas on calcareous clay and Jurassic limestone bedrock. The new sandy vineyards near the Atlantic, located on the lower valley floor, include Malvasia de Colares, Arinto, Galego Dourado, Castelão, and ungrafted Ramisco. Additionally, more Malvasia de Colares is grown higher up in calcareous sand on Jurassic limestone bluffs overlooking the Atlantic.

Joachim and Alex have chosen a more daring approach for some sites: rather than trenching down to the clay and backfilling with sand, they planted long shoots (ungrafted) directly a meter to a meter and a half into pure sand. The vines sent roots down and quickly grew strong. Ramisco, in particular, already had abundant bunches after the first few years. In Janas, the vines are grafted clones on SO4 rootstock (Selection Oppenheim 4); in sand, all are massale selections.

They practice plowing only once a year—after harvest and before winter rains—then they seed lupin, vetch, and berseem clover as cover crops, which hold moisture, improve soil life, and protect against erosion. Water is scarce, even when the air is constantly humid, and cover crops are more essential than ever. They use less than two kilos of copper per year, alongside silica and seaweed extracts. Vineyard densities are 5,000 vines per hectare in limestone and 3,000 in sand. The DOC Colares defines yields by hectoliters per hectare (55 hl/ha for reds, 70 hl/ha for whites), but there are no regulations on density.

Joachim and Alex are aiming for organic certification in the near future and perhaps biodynamics thereafter.

White wines from Colares and Portugal in general often age with unusual ease (as do the reds). High acidity and low alcohol lead to better whites, but indigenous varieties like Malvasia de Colares and Arinto also contribute greater phenolic structure, which provides grip and oxidative resilience.

While Arinto is not a large part of Colares’s DOC, its adaptability has made it increasingly common in the region. It handles heat, wind, and varied soils while retaining acidity and structure. In Colares, it complements the quality of Ramisco and Malvasia, widening the stylistic range under the Lisboa IGP classification. Arinto always brings a more muscular column on which other varieties can lean, a silent architecture of strength. But it is also more than scaffolding; it’s perhaps the country’s most dynamic white grape, the backbone of many Portuguese white wines.

Raw materials only realize their full potential under the hand of quality craftsmanship and passed-down experience. Not quite embracing modern techniques and tinkering, traditional cellar methods in Portugal likely reinforced this through long lees contact, larger wooden vessels, and restrained oxygen exposure. And in many cases, a straightforward, hands-off, and patient approach centered on a belief in the quality of a terroir results in the best and longest-lived wines.

Across Colares, the Dão, Vinho Verde and Bairrada, the variation of high-quality rock and soil types famous the world over for producing wines of character—igneous, metamorphic, and sedimentary rocks (particularly notable in the latter, limestones), and the mostly free-flowing Atlantic influence gives many of Portugal’s whites their characteristic tension and length.

It’s been my experience that many of the ancient bottles found across Portugal in various restaurants and retail stores were subjected to annual temperature fluctuations through inconsistent storage techniques, and though they almost always have cheap corks (ironically, in the land of cork!) many still manage to thrill—a testimony that their foundations of grape, cellar, and place were stronger than their circumstances.

The whites of San Michel have many faces, but two notably distinct ones. When these young wines are served colder than usual, they can be more easily mistaken for a broad-shouldered, muscular style of Meursault–more old-school than new: think 1990s François Jobard and the lovely stout and even hard mineral quality with that pure white Devonshire creaminess. I know the comparison is all too common, but it applies here. We’re dealing with the same geological building blocks: Jurassic limestone bedrock and white calcareous clay. The key differences are the Atlantic climate versus the continental, and varietal nuance and cultural taste; the latter, under Alex’s nose and hand, is on par with what one might see in a Côte d’Or cellar. Like many growers in Meursault, even their cellar is above ground. When the wines are served less chilled and are open for a few hours, the separation becomes more apparent, not in the shape of the wine, but in the greater expressions of the terroir.

When served on the cooler side, returning to the Côte d’Or comparison, they are closer in spirit to downslope wines rather than upslope: expansive and powerful with a dense core versus lift, angularity, and verticality, respectively, and with similar mineral qualities. Arinto, one of the world’s most talented white grapes, displays the same boundless adaptability to a variety of soil types as Chardonnay, but perhaps none more compelling than limestone and clay—consider Bairrada in Portugal, grown on similar geology. Malvasia and Galego Dourado start in the same direction, but Galego Dourado quickly splits off after the attractive reductive elements subside, and Malvasia does so much earlier than Arinto but holds the shape. Over the entire range, Alex’s gentle reductive touch in the cellar reinforces this distinctive link.

When the wines are served closer to room temperature, the differences become sharper—more cultural and varietally led. By the second day, the distinctions between texture and aromatic profile are undeniable, though the shape still holds. Arinto seems to maintain a straighter line from where it began, while Malvasia layers on the charm with the smile often hidden in the seriousness of Burgundy whites. Galego Dourado breaks away from its reductive notes and starts to pile on the spice, drawing a much greater separation.

It’s a compelling range, one that could unsettle even confident blind tasters, especially in those first hours when the wines are kept cooler and the aromatics are slow to emerge. Unlike many that mimic the Côte d’Or in style but not in substance, the congruence here is real and identifiable—at times, uncanny. This author believes the strength of the connection lies primarily in the terroir rather than the cellar work, which in turn binds these regions’ varietal connective tissue even closer together.

Perched on the mild, south-facing slopes above Janas at 200 meters, the estate’s parcels in this area share a common geological spine: medium to medium-deep calcareous clay over Jurassic limestone bedrock: a combination that tempers the sun and channels a cool mineral energy into every wine.

Across the range, fruit is whole-cluster pressed (or direct-pressed in the case of Galego Dourado), naturally fermented, and taken through full malolactic conversion. Each wine is lightly filtered at 1.2 microns (enough to clarify without stripping; not a sterile filtration) and never fined. Alex calls himself a no-lab winemaker; though he runs basic analyses, taste is what always decides.

Malvarinto de Janas, a portmanteau of Malvasia de Colares and Arinto, is drawn from a single hectare planted in 2013. This marriage of varieties brings both textured muscle and lift. It spends ten months on the gross lees, in an average three-year-old 225-liter French oak barrel, of which 15% is new—just enough to sculpt and frame without intrusion.

The Malvasia de Janas comes from a 0.6-hectare plot planted in 2015; its namesake variety expresses itself here with a quiet, saline depth and inviting spice, floral, and soft white fruit nose. It also sees ten months on gross lees, but in slightly older French oak, averaging four years of age, serving as a neutral stage for the grape’s intricate aromatics and slightly glycerol mouthfeel.

Curtimenta returns to the same hectare as Malvarinto but takes a wilder route. The fruit spends fifteen days on skins before pressing, then ages for a year in a mix of four-year-old French and Hungarian 225-liter barrels. The result is a deeper, more tactile wine, with the structure of its varieties amplified by skin tannin.

From the 0.6-hectare Arinto parcel planted in 2015, the varietal bottling is shaped by twelve months on lees in four-year-old 228-liter French oak, with this middle-aged wood offering a touch more oxygen exchange than much older barrels and a subtle roundness to Arinto’s naturally broad, potentially square disposition.

Galego Dourado, the newcomer, was planted in 2020 on a 0.3-hectare soft slope. It’s direct-pressed and fermented in steel, then given a brief six-month rest on lees in a well-seasoned six-year-old 228-liter French oak barrel. This approach captures the variety’s freshness while allowing a slow, quiet layering of texture.

They also produce a method champenois that’s out of this world. (I’m pleasantly surprised by the overall elevation of sparkling wines across Europe in places not known for them. So many are on the rise to step into the pricepoints that Champagne left on the table—well, at least for now.) Sadly, they produce so few bottles that there is nothing available for export. Maybe one day …

Together, their wines reflect both the constancy of place and the individuality of each planting, each cuvée shaped by its own small variations in vine age, variety, and élevage, but united by a shared origin in Janas’s calcareous soils and the patient, deliberate work in the cellar. With the expansion to 7.2 hectares and a new cellar in the works, production will soon grow from 15,000 bottles to 35,000–40,000. The new cellar, built with solar panels and rainwater harvesting, reflects Alex and Joachim’s vineyard philosophy of sustainability, patience, and the belief that healthy vines and careful choices create wines and a legacy that will endure.

Malvasia de Colares is the primary variety permitted in Colares whites. Marked by sharp acidity, salinity and waxy texture with occasional complexing oxidative tones as they age, and its aromas are enchanting—more effusive than stoic. In sand, these wines are lifted and fine; in clay, they are potent and more muscular. Both beguile with lifted, mineral-laden aromatics and fascinating textural differences. For this taster, Malvasia de Colares, and the many Malvasia biotypes in Portugal (which are genetically different from those of Italy’s massive stable of Malvasia varieties, making this name especially confusing), along with unsung varieties of Italy, like Campania’s Biancolella, Liguria, Corsica and Sardinia’s salty Vermentinos—to name but a few–bottled sun and smiles, all. This is the face of Malvasia in the Sintra-Colares area, though those grown in Janas at San Michel dance between serious and playful.

While Malvasia de Colares defines Colares’s white wines, Ramisco is its sole red variety. It produces small berries with thick skins and ripens late under the region’s steady Atlantic influence. The wines show high acidity, firm tannins, and moderate alcohol (typically around 11 to 12 percent). They require extended aging—often years in barrel and bottle with many excellent examples of well-aged and worthwhile Colares reds from producers like Viúva Gomes. San Michel will harvest their first own-rooted Ramisco from sandy soils in the Colares valley floor in 2025.

The Colares DOC wines of San Michel will likely find their way to our US shores around 2028 or 2029.