Concrete vat in the cellar of Domaine Mont de Marie

There’s too much to talk about in February to consolidate into a single newsletter. The second part will be an early stand-in for March’s Newsletter and will be published next week on Friday, February 13th—scary … In the second part, I will reintroduce two new players on the Saumur scene. Our first vintages we imported from both were just two years ago, but they’re maturing in craft and vineyard evolution faster than an AI updates its language model; the gamble is going to pay off big with these two. But that’s our favorite thing: finding those talents no one knows before they’re known—before they’ve proven their merit, been colonized by the hype machine and turned into stars. Those domaines are Fabrice Esnault’s Domaine la Giraudière, making Brézé and Saumur-Champigny wines, and Gilles Colinet’s Forteresse de Berrye, making Chenin bubble and still, and Cabernet Franc from inside Saumur’s Puy-Notre Dame. The prices of their previous vintages are tough to match, but wait till you get a load of them now with their 2023s and 2024s starting to roll in.

Before we jump to Italy and Spain, let’s start with France, where last month left off: David Duband.

France

A New Duband

Les Terres des Philéandre | Côte d’Or & Hautes-Côtes de Nuits

Available From The Source in select U.S. states

Monsieur Duband has a newish project (started in 2018), a portmanteau created from the names of his twins, Philomène and Léandre: Les Terres de Philéandre. While he’s best known for his meticulous stewardship of some of the Côte de Nuits’ most prestigious appellations, this deeply personal project was born from a desire to work with greater freedom at the margins of Burgundy’s formal hierarchy—to step back into something quieter, more intuitive, and perhaps even more revealing. With only a few parcels in Savigny-lès-Beaune, the grapes for this project are primarily sourced from the Hautes-Côtes de Nuits, just adjacent to his classified vineyards, and are often labeled as Vin de France (VDF). These wines draw from medium-aged to old vines rooted in clay-limestone soils and shaped by the same rigor that defines his domaine work, with whole-cluster fermentations, native yeasts, gentle extraction, long élevage, with sulfites added only after malolactic fermentation—or not at all where the wine allows. Les Terres de Philéandre doesn’t sit apart from Duband’s core work; it quietly completes it.

Les Terres de Philéandre fills a continually widening gap on shelves and lists for years: Burgundy that smells, tastes, and seems like what it is, priced fairly, without feeling diluted or like the result of a quiet cellar declassification. The Hautes-Côtes areas just to the west of Côte de Nuits and the Côte de Beaune share the same basic geology, and they will matter even more as the landscape continues to shift due to climate change. Like many wines from the Hautes-Côtes, these wines feel like a preview of what’s coming. Once again, we’re able to drink “value” Burgundy that doesn’t ask us to lower our expectations.

Both TdP 2023 whites strike a higher chord than one might assume, considering their appellation classifications. Both come from vines in the Hautes-Côtes de Nuits, just adjacent to HCdN parcels with the VDF Chardonnay “Le Blanc” from 30-year-old vines that reads nearly as much like an Aligoté as a Chardonnay; the Côteaux Bourguignons Chardonnay tastes like Chardonnay. It comes from 40–60-year-old vines, both facing southeast on steep clay and limestone slopes. I know–you’ll have to taste ‘em to believe it. You’re right, and you’ll see what I mean when you do. It’s rock-solid, with no extra trim, no tinkering, just clear and focused white Burgundy.

Unlike the two Chardonnay-based TdP wines grown in old French Burgundy barrels, the Bourgogne Aligoté was aged in a combination of 30% concrete egg, 30% in a 25 hl Stockinger foudre and 40% in steel to build texture without masking its natural tension. These grapes come from 50-year-old vines in the Hautes-Côtes de Nuits, facing southwest on steep clay and limestone slopes.

The 20-year-old (2026), high-altitude vines for the VDF Pinot Noir on steep, east-facing slopes just next to Duband’s HCdN vines underwent whole-cluster maceration for 10 days, with one daily pumpover during the first four to five days, followed by foot pigeage three times per day over the final five days to release maximum sugar before pressing. The wine was aged for ten months in 228-liter French oak barrels ranging from one to five years old. Sulfites are added after malolactic fermentation, and there’s no fining or filtration.

I admit it: we made a mistake with Célénie. I’ve always had reservations about ordering no-added-sulfites wines, even from top technicians. Indeed, we have quite a few wines like this now, but we scrutinized them all heavily before buying. Yet here we are with this Hautes-Côtes de Nuits Rouge ‘Célénie’ as one fabulous example of a sans soufre wine gone completely right, and we’re in very short supply—only until we get more. After getting a little bored with the classical Burgundy profile of fruit that is often even a little tired compared to some of the regions we work in, when I poured the first taste for my wife (who doesn’t drink much anymore), she looked at me like I’d asked her to marry me again and said, “Now this is my style of wine.” Then, when I tasted it at the cellar in December with our San Francisco boss, Marissa, her first reaction was excitement, and then regret: she didn’t request any when I placed our first order for the 2023s because she, like everyone else, wanted to taste them before jumping on the Duband Sans Soufre Soul Train. Three wines into our 25-wine tasting, we pleaded, David scrambled, and now we’ll have a few more cases on the water destined for the warehouse in March or April. These grapes, harvested from 50-year-old vines in the steeply sloped Hautes-Côtes de Nuits, underwent whole-cluster maceration for 10 days. There was one daily pumpover during the first four to five days, followed by foot punchdowns three times a day over the last five days to release maximum sugar before pressing, then aged in a Stockinger foudre. No added sulfites, no fining, and no filtration. This is yet another testament to sans soufre wines’ success when left to those who have mastered the fundamentals first. Congrats to David and to his son, Louis-Auguste, who surely spurred his dad into doing this experiment. What a wine!

We’ve had a lot of interaction with Savigny-lès-Beaune over the years; early on, we imported Simon Bize, Jean-Marc et Hugue Pavelot, and Bruno Clair, and it’s nice to have some wines from this underrated place. David has a few different ones, but we went with his appellation Savigny-lès-Beaune Rouge and the 1er Cru Aux Serpentières both from 50-year-old vines (2026) and vinified the same way in the cellar: 70% whole clusters and macerated for 10 days, with one daily pumpover during the first four to five days, followed by foot pigeage three times per day over the final five days before pressing. It ages for 13 months, in 40% new oak 228-liter French barrels, with the first sulfites added after malolactic fermentation, and no fining or filtration.

Hautes-Côtes de Nuits vineyard where many of Duband’s wines come from

François Crochet

Sancerre

Available from the Source in select U.S. states

We don’t promote François Crochet’s wines very often because so many already know them well, everything sells so quickly, and we never get enough to meet the demand. Here’s a quick reminder of his story and the arriving wines.

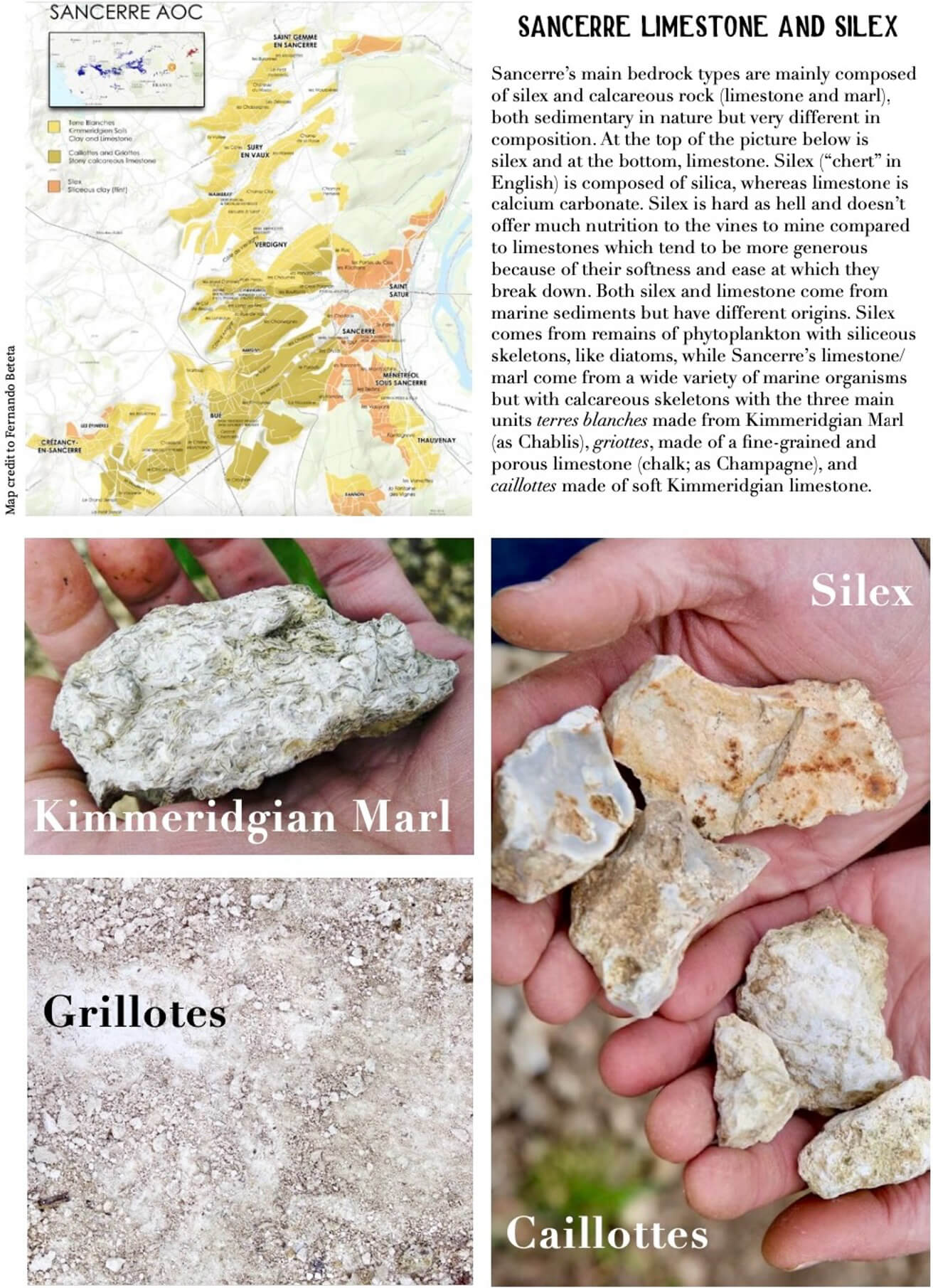

After enology studies and stints at many wineries (highlighted by Domaine Bruno Clair), François took over his father’s Sancerre winery in Bué. Approximately 11 hectares on 30 parcels display a range of aspects from flat to steep, and north to south. Most of the grapes are the lieux-dits Le Petit Chemarin, Le Grand Chemarin, Le Chêne Marchand and Les Exils. Certified organic and working with biodynamic methods, the terroirs range from Kimmeridgian limestone marls, silex, various other limestone formations, and iron-rich clay. He’s one of the first growers in the appellation to pick, and the whites are whole-cluster pressed, fermented, and aged in steel or old tronconic oak vats. François’ Sancerre Rosé is made entirely from Pinot Noir and undergoes a short maceration with the fermentation and aging in steel. While a master of white, his reds are also revered in his appellation and are fermented in stainless and aged in old tronconic oak vats. They’re unfined, lightly filtered, and contain added SO2.

Wines

What’s most interesting about François Crochet’s entry-level Sancerre Blanc is that it is an assemblage of dozens of small vineyards from every aspect (north, south, east and west), various geological formations, including the hard, silica-based sedimentary rock (silex, or chert/flint stone), limestone formations of soft, powdery chalk (referred to locally as grillot), medium-hard chalky limestone (caillottes), and other limestone marls. Aside from the mix of tiny parcels too small to have their own cuvée, most come from the vineyards that are bottled as single-site wines. Fermented and aged solely in stainless steel, Crochet crafts an energetic, mercurial style of Sancerre with fine lines and pointed complexities.

A compilation of different sites within Bué, a commune in the western area of Sancerre, Les Amoureuses is a blend of three parcels with heavier clay topsoil than any others within his collection. The name, Les Amoureuses, translates from French as “the lovers.” The clay-rich soil makes Les Amoureuses a freight train of Sauvignon Blanc, and the most powerful and generous wine in François’ range of white Sancerre—it’s a crowd pleaser.

Planted in 1976, Le Petit Chemarin showcases ethereal high-tones and strong mineral nuances. Its first vintage was 2014, and it quickly moved to the front of the pack then and every year thereafter. The bedrock here is limestone formed by a coral reef about 150 million years ago. This wine is made nearly the same as all the other crus in François’ range; it’s unique in its own way and stands apart from the entire range in polish and delicacy. Le Petit Chemarin was used for the basic Sancerre white, but after years of vinifying it separately in the cellar, François recognized its merit as a single-site bottling. We couldn’t agree more. It’s one of our favorites because of its unique display of x-factors, strikingly fine mineral textures and sleek profile.

New Grower for The Source

Mont de Marie

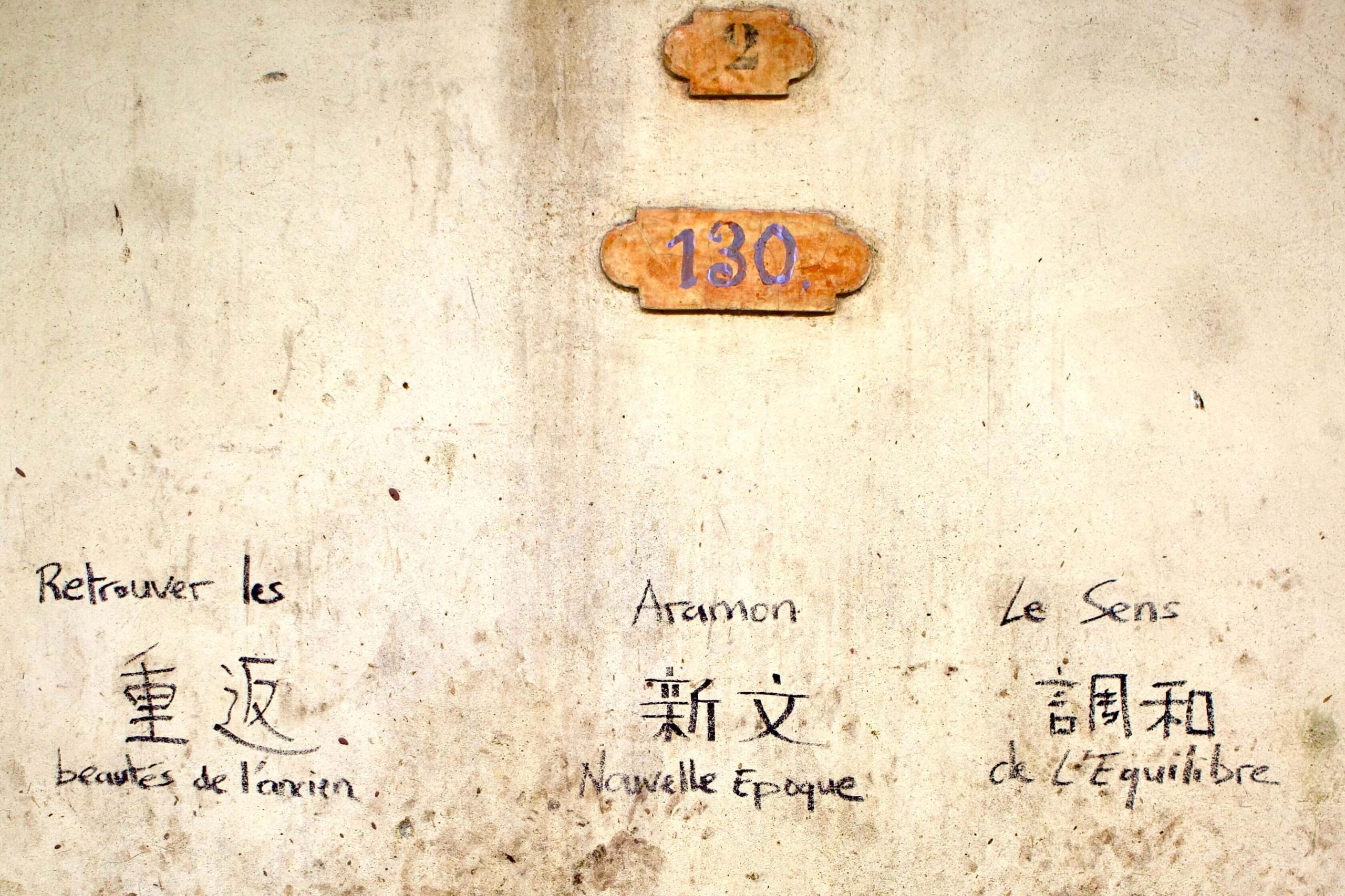

Languedoc – Gard | Southern French Recalibration

Available from The Source in California

Continuing into France, we’ve added another wine producer to our California roster that fits into the game-changer category. The south of France has a well-deserved reputation for powerhouse red wines and far less for subtlety—at least inside a more delicately framed wine. That’s not to say that powerhouse wines cannot be elegant, but I’ve long wondered why the sunniest places in mainland France strive for power to appease critical press when the local fare and climate themselves often ask for the opposite. When I’m there, which is at least a couple of weeks every year, I want an ethereal wine that matches the ambiance, not a hefty one, which is all too common. This is what draws me to Domaine Mont de Marie, where I’ve found an elegant portrayal of regional specificity in the south, in this case, the Gard, that strikes the resonant chord I’ve long been missing.

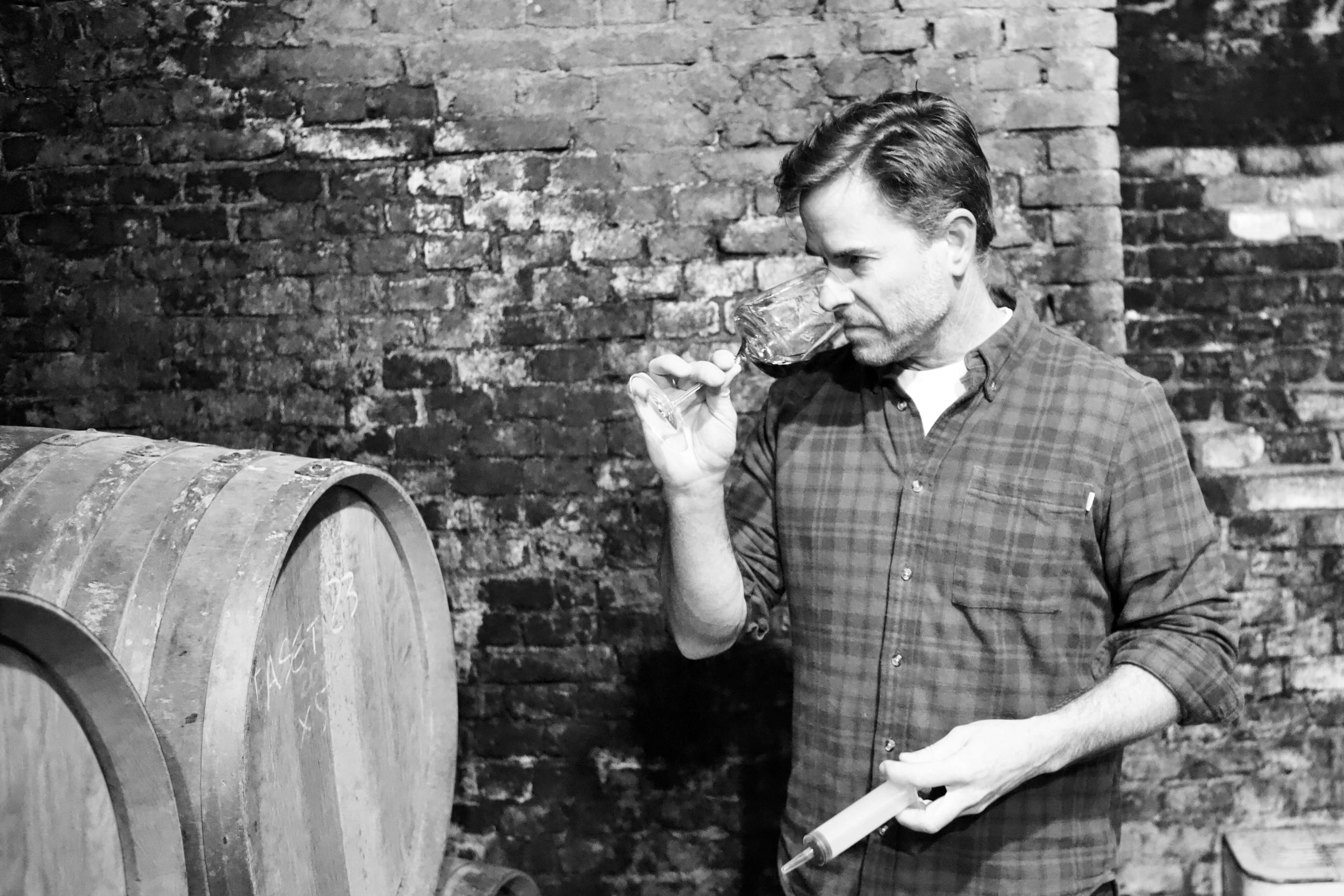

Thierry Forestier and his wife, Marie-Noëlle, and their Domaine Mont de Marie are a wonderful addition to our collection of growers. It was indeed happenstance that I first visited him a few years ago, while moving through the south toward a run of cellar visits in Jurançon, Cahors, Bordeaux and then up to the Loire Valley. As we tasted before lunch, the wines really surprised me. I thought it would be a quick in and out, nothing to say but thank you very much and best of luck to you. But while different in overall shape and expression than the domaines to follow in the next few days, these were as compelling as they were unique. At the time, Thierry was settled in his national agenda with his U.S. importer, and, with a wonderful taste in my mouth and some confidence in the region’s need to recalibrate toward more elevated, less burdensome wines, I bid him and Marie-Noëlle farewell. Then I was pleasantly surprised when I was welcomed back mid-year last year to talk about more than just the wines.

I love Thierry’s wines; they bring me so much pleasure and downright thrill me. They demonstrate what can be accomplished in the south of France when one consciously farms to pick the fruit at alcohol levels around 12%, with some a little lower and some a touch higher. Their range of natural wines, most without any added sulfites, is shaped as much by wild herbs and scrub as by fruit, with his entire range striking taut aromatic chords and channeling emotion as though the wines are alive themselves and happy to be part of the moment.

Located on the rocky landscape of Souvignargues, directly 20 minutes west of Nîmes, their twelve hectares of organically farmed Carignan, Cinsault, Grenache, Ugni Blanc, and the rare aromatic and fine red, Aramon, are surrounded by all those wonderful herbs that seem to infuse the wines rendered from them: lavender, thyme and rosemary and their gorgeously aromatic flowers in bloom in spring, laurel, chamomile, sage, and ciste. The ancient alluvial soils of sandy clay, red iron-rich earth, flint, and rolled “poudingues” stones, with deeper conglomerates, lend natural drainage, restraint, and pointed structure for these fine nuances and gentle but aromatic wines. Cooled at night by air descending from the Gard’s Aigoual massif, complementing the burning summer sun and the Mediterranean and African winds from the south, his stable of old vines (50-100 years old) produces small, balanced harvests of taut, early-picked fruit that retain their aromatic purity and delicacy.

Thierry’s love for nature shifted him from a career in tech to a life immersed in farming, foraging, and viticulture, where he observes, rarely touches, and finishes his wines with purposefully clean and precise craftsmanship. Across his cuvées raised in neutral vessels (concrete, old large foudre, well-seasoned barrels of many different sizes) the through-line is freshness and clarity, a conscious selection of fruit in its earliest ripening phase that flutters yet remains taut with bright lift and modest alcohols, especially for this southern French area known for intense summer heat, while still grounded by the wisdom of his old vines. His commitment to preserving the region’s heritage varieties, especially Aramon, underpins his production of intricate terroir wines sans artifice.

His best-known wine is Anathème, which he makes in both white and red, both of which we’ve imported in our first year with him. Calling a wine Anathème (anathema in English) is Thierry putting a name to his idea that once you stop trying to please everyone, the wine is finally allowed to tell the truth. It’s sure that neither Anathème wine is what one expects from this area that soaks up some of France’s hottest summer sun and warm winds.

The varieties behind these wines were largely discarded after WWII, but not because they lacked quality. Aramon and Ugni Blanc, for example, were not abandoned because they were difficult to grow or low yielding; in fact, both naturally ripen late and yield a lot. But they fell out of favor as markets shifted toward darker, richer, higher-alcohol wines, while perfume, acidity, nuance and finesse were deprioritized in favor of heavier impact.

Carignan, which makes up 90% of the Anathème red, followed a different path. Once widely planted across southern France, it was progressively pushed out as Grenache proved easier to manage, ripened more reliably, and could flex across multiple styles from rosé to powerful reds that aligned with the styles the market demanded. A similar consolidation unfolded just west in northern Spain, where broad plantings of indigenous varieties (like Garnacha/Grenache and Mazuelo/Cariñena/Carignan) gave way to Tempranillo, not because of inherent superiority, but because it adapted more cleanly to trellised systems and postwar mechanization. Across both regions, this was not a judgment of quality, but a narrowing driven by commercial alignment.

Thierry’s southern French wines are not corrections of a warm and sunny place, but a recalibration of what we’ve come to expect from it.

When I first tasted Thierry’s Anathème blanc, I thought, “Who in our supply chain wants a white wine from these parts?” But without it, the complete story of Thierry’s approach would fall short with only the reds in tow. It is indeed worth seeing what he accomplishes with white grapes, again, from one of France’s hottest regions during summer. It’s all about calibration and expectations on the overall profile. The gentle whole-cluster pressing and natural fermentation in 10-year-old, 400-hectoliter French oak keep the wine truer to form and terroir, without too much hand in the wine. Sulfites are added to this cuvée after malolactic, and there is no fining or filtration. Composed of 80% Ugni Blanc with Viognier and Grenache Gris from vines planted in the 1960s. The two bottles of 2023 I tasted had a broad range of nuances that unfolded over a few hours after opening. Everything from warm citrus to early-season stone fruits, light honey, solid minerally nuances with wet forest floor.

The Anathème rouge is Mont de Marie’s business card. 90% Carignan and 10% Aramon planted in the 1950s, this is jovial, well-balanced and very perfumed rouge—a capture of whole clusters and the built-in floral and herbal aromas that swirl in the scented winds of these parts. Over seven days of maceration, it’s untouched and maxes out at 24–25 °C. This limited-temperature and infusion approach lifts the finer floral and ethereal nuances and balances out its savory backdrop. It’s aged for nine months in very old 130-hectoliter concrete vats. There are no added sulfites, no fining and no filtration. This wine is best served on its first day to ensure that it stays in its jardin de fleurs et de fruits.

“Greetings to the field!” is a loose translation of the Latin in the name Salve Ager. It’s also used in Italian and French while saluting (salut). Ager means field in Latin, so the name is a slight (possibly unintentional?) homage to the Reynaud-like delicacy, save the monster alcohols of Château Rayas; of course, I do understand that I’m taking liberty with this reference to one of the world’s most singular and extraordinary growers, but I’m mostly just looking to describe its profile rather than its pedigree. Here, this 95% Grenache and 5% Cinsault is grown on ancient alluvial soils of sandy clay, red iron-rich earth, flint, and rolled “poudingues” stones, with deeper conglomerates, facing west on gentle slopes. The sand makes a big difference with this beautiful wine built on Grenache’s finest points—perhaps attributable to its Rayas lean. To build on this theme of grace and subtlety, it goes through a whole-cluster, seven-day natural infusion (no extractions) with fermentation at 24–25 °C maximum before pressing. Again, like Anathème, this medium temperature and aging in 80 hl concrete tanks for nine months allows this wine to retain brighter flowers and fruits that decorate its otherwise earthen and metal-gilded frame. Here, there are no added sulfites, no finings and no filtration. In the wine world, it’s much easier to make wines at this price that speak loudly and broadcast their high value, but Thierry has done the opposite: an elegant wine that floats well above its price. This is one of Thierry’s strongest positions: he doesn’t want to get on an airplane to sell it in person to get a higher price. He prices it right so they can sell easily on their own merit.

Coquin de Sort is a mild, old-fashioned French exclamation of slight annoyance, surprise, or exasperation, which is translated literally as “rascal of fate” and meaning “what the devil?”. It’s a polite, slightly theatrical way of reacting to bad luck or an unexpected turn. In this case, the first Coquin de Sort started as a surprisingly delicious vat some years ago, so he decided to bottle it, and then it became an annual occurrence. It comes from 60% Cinsault and 40% Grenache. Burned into memory, the bottles I had last year recall the wine’s aromatic draw of Persian mulberry-like exoticness intermingled with sweet greens, like lime, wheatgrass, and fresh bay plucked right from the plant and crumpled up in hand to release its aroma. On the palate, it was elegant and refined with a balance of petrichor, forest floor and wild berries, another wine impossible for us to ignore. In the cellar, it was whole-cluster fermented over seven days at maximum temperatures of 24–25 °C before pressing. To keep it tight and true to form, it was aged nine months in 25 hl concrete vats. No added sulfites, no fining and no filtration.

Like all no-added-sulfite and more hands-off wines, Thierry’s wines may need even a few more months after their transatlantic voyage to settle and find their magnificence. I’m sure they’re revealing many cards early on, but they will have even more to share in the next few months.

Italia

Brandini

Barolo | High Elevation

Available From the Source in all U.S. States, except TX

This month, the exciting new 2021 Barolo La Morra crafted by the hands and mind of Giovanna and Serena Bagnasco and their team has arrived. We’ve been waiting for this one since we started our collaboration at the beginning of 2022. They already nailed the 2019 and 2020 versions, but this one just might top them.

Gio’s Words | 2021 Barolo ‘La Morra’

“As most people know, 2021 was great. One of the most important factors was the winter of 2020 and 2021, which was the snowiest one I’ve ever experienced. We had a lot of snow and very cold temperatures, and after two consecutive years of fairly severe drought, this finally restored the water table. The vineyards went into hibernation, regained nourishment and energy, and entered spring in excellent condition.

Spring itself was not too warm. Toward the end of May and into June, there was some rainfall, which meant the flowering was not excessive in quantity. Summer, however, remained very balanced, with some rain and no extreme heat events. By the end of the growing season, we had what I consider a great contemporary vintage. It leaned more toward the warmer side than the colder, but it maintained its balance, and the vines were never significantly stressed from heat. The wines show remarkable aromatics and an approachable character, while still maintaining structure, backbone, and the complexity needed for aging.

Comparing 2021 to another year, I’d say 2019 is probably the closest. The 2023 vintage shares some aromatic similarities, but the weather conditions were very different, so it’s not truly comparable in terms of the season.

The 2021 Barolo La Morra is a blend of the four vineyards we have in La Morra, all located on what we define as the commune’s occidental side. They are all within less than a kilometer of the winery, near Brandini, and all face toward the Alps on the back side of La Morra. The sites differ in altitude and exposure. Sant’Anna sits much lower than the latter; then there is the lower portion of Brandini, followed by Marmo and San Bartolomeo. They are all adjacent to the property, but each faces slightly differently and sits at a distinct elevation.

As always, I harvested and vinified each vineyard separately, creating four individual tanks. After alcoholic fermentation, I combined them two by two, pairing the lots that were closest chronologically. I then submerged the cap for an additional ten to twelve days to complete maceration, followed by the final blend before aging. The wine spent twenty months in barrel before bottling.

I have to say that I truly love the 2021 as a vintage, especially for La Morra, because it is unmistakably La Morra. It expresses elegance, finesse, aromatics, lift, and brightness, along with a certain approachability. That is something I value greatly in our work. It’s rewarding to have a Barolo that is ready, open, and softer in character, while still clearly being Barolo.

Of course, it has nothing to do with the austerity and introverted nature of Barolos from colder vintages; instead, it reflects sunshine and climatic balance, while still delivering complexity, structure, and depth. All things considered, among the Barolos currently available, the 2021 is probably the one I am most proud of.”

Fletcher

Langhe & Barbaresco | Non-Nebbs

Available From the Source in all U.S. States, except NY & NJ

Five of Dave Fletcher’s non-Nebbiolo 2024 wines have landed. Below is a softly edited version of his take on the vintage without daring to touch his charming Aussie colloquialisms.

Dave’s Words | 2024 Vintage

“2024 is a bit of a mixed bag across producers, a lot like 2022, where there’s a heap of crap out there. I think the journalists are having a go at it because of the rainfall. If I tell you there was a lot of rain, cooler weather, and disease pressure, you can interpret that however you like. What matters is who worked hard in the vineyard. Clearing fruit, dropping it at the right time. I did it four times in some of the vineyards I was working with—opening canopies, treating properly. I still had disease, but that’s where sorting and selection come in. You work harder to get the best fruit. The 2024 Langhe Nebbiolo, 2024 Dolcetto, and 2024 Barbera are, for me, screaming examples of the vintage.

At the end of the day, yes, it rained, and yes, it was cool. You can see the hallmarks of a cooler vintage. So whatever gets written about rainfall or whether it mattered or not, I’d say just focus on the wines you’ve actually got in your hand. And the wines, honestly, are frigging great. This year’s Langhe Nebbiolo in particular is something special. I reckon it’s one of the best wines I’ve ever made. It’s bloody delicious. Just taste the wine.

Dave’s Words | The Wines

2024 Favorita: Very elegant on the nose, as always. Pear and citrus straight out, with some straw notes coming through from the nine months on lees in old wood. There’s a nice glycerol texture that gives it length, finishing with fine, clean phenolics.

2024 Chardonnay ‘C24’: This is bang on the style I’m chasing. The nose has a really broad spectrum, starting with citrus from the early-picked fruit and moving into that honeydew melon and peach zone. You get touches of honeysuckle and very delicate oak from the 30% new barrels, all low toast. Nine months on lees and a turbid fermentation give the wine real body, balancing the acidity and dragging the finish out for days.

2024 Dolcetto d’Alba: A ripping Dolcetto from a cooler vintage, and it really shows how adaptable this grape is. I haven’t tasted a Dolcetto this floral in a long time. Violets and rose petals jump straight out of the glass, instantly inviting. The palate has proper, age-worthy tannin, but it’s kept in check by the softer acidity, which also helps pull the length right through. You finish with the tongue coated in red berry fruit.

2024 Arcato: (A blend of 75% Arneis and 25% Moscato) This wine never stops keeping my interest piqued. It’s constantly shifting on both the nose and the palate, moving through all sorts of fruit spectrums. One minute it’s all fruits and flowers, the next it’s herbal notes and citrus peel. It’s hard to pin down, but that’s exactly what this wine is about. The low alcohol makes you think it’ll be light, but the three weeks on skins build texture and intensity, adding a phenolic lick on the back palate that gives it real presence.

2024 Barbera d’Alba: Violets, blackberries, and fresh-cut sweet herbs layered on the nose. The use of whole clusters is the perfect way to rein in Barbera at this level of ripeness. It stays pure and elegant, with just the lightest stem character adding intrigue. It’s not heavy on the palate at all, more delicate and poised, with subtle spice sitting quietly in the background.

España

Pablo Soldavini

Ribeira Sacra | Taming the Beast

Available From The Source in all U.s. States

Pablo Soldavini’s ethereal style of wine resonates deeply with us. Moving through a world of top-flight wines built on finesse, brighter red fruit, and an almost inexhaustible energy, his wines can feel startlingly alive when poured alongside other gorgeously crafted classical reds, wines sculpted in pursuit of deep complexity hidden behind layers of fruit, yet which can taste strangely exhausted by comparison.

An Argentine national with a delicate touch in the cellar, Pablo spent many years trying to convince the Ribeira Sacra growers he collaborated with of his direction, Saíñas, Terra Brava, and Fedellos among them. Now, finally on his own and hitting stride, it is all Pablo. His wines echo the flora and fauna of these treacherously rocky high hills, leaving the ruggedness of their steep gneiss terrain to the imagination as much as to the palate.

We are fortunate to work with many talented growers across Galicia. But when traveling with other wine professionals along the Iberian route, Pablo’s name almost always finds its way onto the podium when asked about the most compelling wines of the journey. Today, he has built a new winery that allows him to expand production enough to make a better living. Still, he’s made it clear that he will always remain small, choosing to work alone, readily admitting that he is difficult to collaborate with. From our experience, however, he has always been a pleasure to work for, and he deserves our full attention and our best effort as much as any grower in our portfolio.

Pablo’s Words | 2023 Vintage

“2022 was a very dry and warm year; however, in 2023, in addition to high temperatures, we experienced several episodes of extreme heat, with temperatures close to 45°C for several days. On top of this, there were strong winds that, in the vineyard, acted like hair dryers, dehydrating the leaves and causing the vines to suffer greatly. This caused the vegetative cycle to slow down, and therefore, in some parcels, we had to harvest earlier than usual.” The surprise, and the quiet triumph, arrived afterward. “Curiously, we still achieved optimal ripeness and perfect sanitary conditions.” That paradox, stress yielding clarity, shaped every decision that followed. “This latter point led me to carry out longer macerations, of up to 60 days.” – Pablo Soldavini

Details

All of Pablo’s ethereal-styled wines ferment naturally with 100% whole-cluster, infusion-style extraction, with macerations lasting 45–60 days, followed by 11 months of aging in 300 and 500-liter French oak barrels (hogsheads and demi-muids). They are unfiltered and unfined, with very low sulfite additions. All fruit is grown on gneiss with rocky, sandy, silty topsoil in the Ribeira Sacra subzone Ribeiras do Sil, at 400–500 meters altitude. Tanis comes from 70-year-old (2025) vines of 75% Mencía, 15% other red varieties (Garnacha Tintorera, Mouratón, and Merenzao), and 10% white varieties, primarily Palomino and Godello. Merenxiao is harvested from 40-year-old Merenzao (Trousseau) vines, while Sabela comes from vines planted in 1912, with 80% Mencía, 10% Mouratón, and 10% Gran Negro.

Ponte da Boga

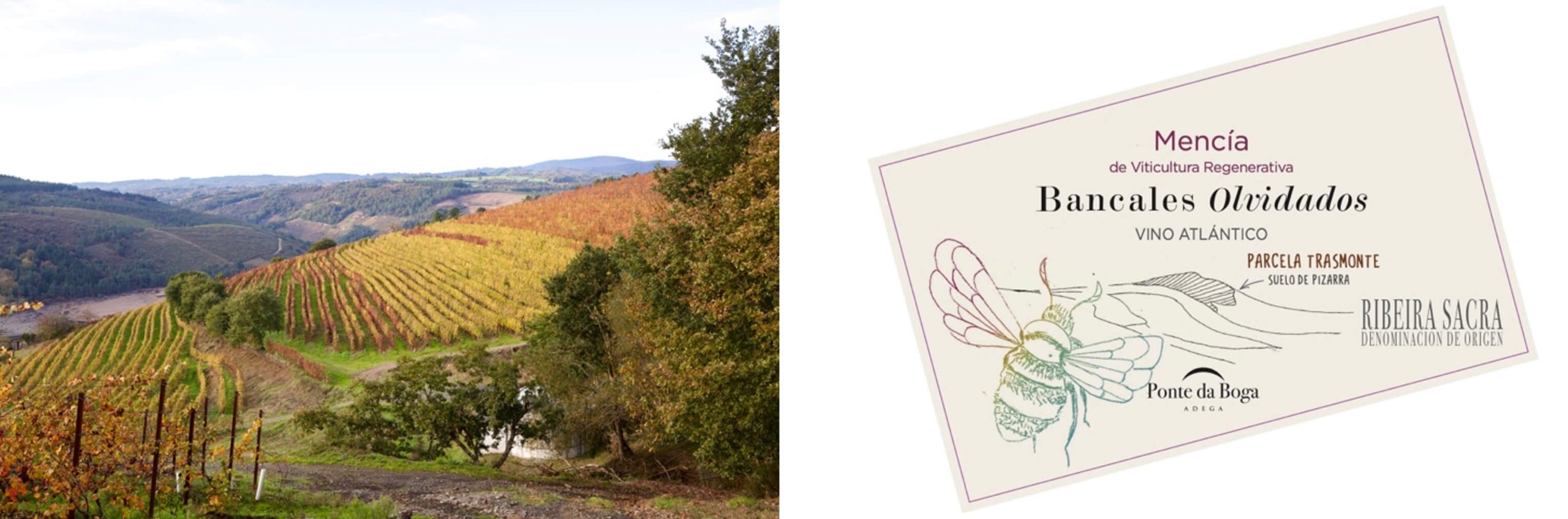

Ribeira Sacra | Change is in the air

Available From the Source in all U.S. States

I talked about this new personal success story quietly brewing in Ribeira Sacra about a year ago, and here we are finally able to get to this organically farmed Mencía from one of Ribeira Sacra’s most historic bodegas, Ponte da Boga. After nearly a year of discussions, and a handful of vineyard and winery visits at Ponte da Boga, I asked Javier Ordás de Villota, their export manager and now our friend, for a meeting with the big boss to discuss the future and a topic crucial to our ethos: true sustainability, ecological consciousness, and a word that, depending on the company, can quickly turn conversations sour: organic farming.

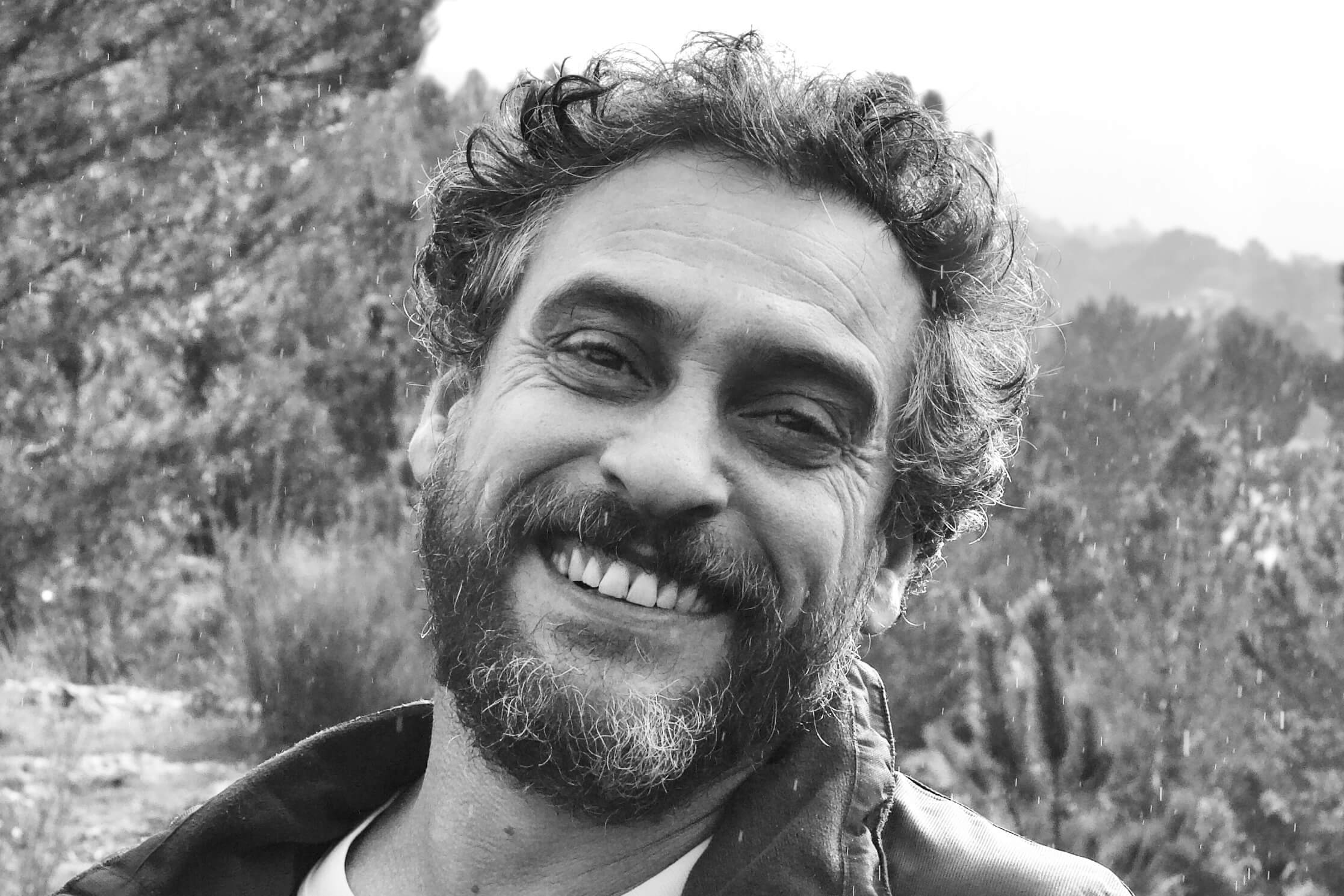

Francisco Alabart, a Catalan native, the Senior Director of Estrella Galicia’s wine and cider projects (including organic ciders), and of course, Javier’s boss, quietly listened to my pitch. I presented many ideas, but principally focused on how Ponte da Boga should take a strong position on organic farming in this region, so that they can become true industry leaders in Galician wine. And just like that, we walked out with a 2.5-hectare commitment from vines at one of Ponte da Boga’s Ribeira Sacra vineyard partners. The vineyards where the experiments will take place belong to the owning family’s son, José-Maria Rivera Aguirre (Jr.), known by all as Chema.

Born in 1991, the easygoing and extremely personable yet shy Chema explained that he’s always had a strong connection to nature and the outdoors. An avid surfer, he pivoted and turned his love of the outdoors toward the vineyards of Ponte da Boga, where he interned for a couple of years starting in 2017. After that, he decided to spend his time in Chantada to grow grapes on his mother’s 40 hectares of wild land, and organic farming was always on his mind. “I was convinced that organic viticulture was possible. And if it’s possible, it was mandatory to try,” Chema said.

It will be tough where he is, but he says that despite its much closer proximity to the Atlantic than Amandi, he doesn’t believe it has a greater mildew pressure, though that will still be his nemesis. He’s all in on 2.5 hectares of the 16 he planted, with five more on the way.

As importers, our role is not just to align, but to sometimes guide and give confidence when it’s needed.

Generously, the team at Ponte da Boga offered us priority for the first organic wines grown on those gorgeous terraces of shattering grayish-blue slate on the northern tip of the Chantada. The wine is the 2024 Mencia, Bancales Olvidados ‘Parcela Trasmonte’. As it’s the northernmost area of Ribeira Sacra, it’s subject to the Atlantic’s coldest whipping winds—exactly what the naturally low acid Mencía needs to preserve its freshness. Tasting various lots of Mencía with Ponte da Boga, the blend dominated by this vineyard was the runaway highlight.

The New Prádio

Ribeira Sacra | Familia Seoane Novelle

Available From the Source in all U.S. States

I do love him, but sometimes Xabi Seoane Novelle can be frustratingly stubborn. When forced with the threat of legal action to continue using the name Prádio, he could have chosen something comparably simple. Instead, he landed on a name with too many vowels in a row and a double L that’s almost phonetically impossible for Americans, unless already good with Spanish: Familia Seoane Novelle. That said, the name shouldn’t deter you.

Xavi has endured a brutal run of years. He began organic, moved into biodynamics, and then, after losing nearly three seasons’ worth of fruit in four years, faced a hard truth: ideology doesn’t pay the bills, and working for nothing but losing money sucks. On the verge of losing the business entirely, he chose to remain committed to organic farming while allowing himself the flexibility to intervene when mildew pressure threatened everything. He chose a good year to remain open, with 2022 being one of the best and easiest years in memory for both red and white wine across the region; indeed, the rest of Europe baked, but the Atlantic made a big assist here, and the varieties that need that extra sun—like those that make up his top wine, Pacio—were picture and palate perfect.

Galicia’s rainfall makes mildew pressure extreme—far higher than in much of Europe—and rigid purity can be a luxury few can afford here. Xavi isn’t compromising quality; he’s protecting it. Growers in Rías Baixas came to this realization earlier out of necessity, and those further inland are now learning from experience rather than theory. 2022 was an exception, and this shows in the balance of the beautiful wines.

Before wine, he spent years as a professional futbolista in Spain’s second division, which is still well paid, disciplined, and relentless. Every euro he earned went into this project, along with the rebuilding of his local culture. Xabi is a bit of a local hero, and he’s put his small-time fame to work by building a very cool hotel, buying the local restaurant, and fixing it up to serve not only wine to passersby but also the entire village, who get a great meal for a great price.

Failure for Xabi could no longer be an option, and stubbornness tied to ideology in Chantada, the furthest western subzone and perhaps the coldest of Ribeira Sacra, would have been irresponsible. Our support comes from an understanding of the man, the work, and what it actually takes to farm this place without illusions. He’s still farming organically, but he’s now a flexidealista—a new word. He’s still making excellent wines, and his livelihood is no longer threatened by mildew. But hail, drought and frost are another story.

2022 Mencía

After all these difficult years that tested his grit in the vineyard and sharpened his mind in the cellar, his 2022 vintage is a breakthrough. The 2022 Mencía is very good—woodsy at the start (like the smell of the surrounding wild forest rather than barrels), a pleasure to drink, complex and genuinely pretty, with a flawless throughline of sumptuous fruit inside a very minerally and metal frame imparted by his architectural contour model set on the convergence of granite and schist that cuts the vineyard in half—dead center. The nose opens with a touch of reduction that briefly holds it at bay, but quickly dissipates.

2022 Pacio Tinto

Still, the real story here with Xabi isn’t necessarily his Mencía—it’s his Pacio. He knows it. We know it. Xabi says his dad doesn’t always agree (a big Mencía guy), and neither do most people who think about Galician red wines. Mencía grows best on the ancient acidic soils derived from the Galician–Iberian Massif: 300-plus-million-year-old eroding rock of slate, schist, gneiss, and variations of granite-granodiorite, at high altitudes, to preserve some freshness.

The high-end red wines that most resonate with me in Galicia aren’t likely to come from Mencía; there are, of course, notable exceptions, including Envínate, Guímaro, Seoane Novelle, Pablo Soldavini, and a small handful of others. The most compelling wines come from its ancient varieties, which don’t just perform well but more fully define this place and its cultural heritage prior to Mencía’s arrival.

Because of its early malic acid respiration and tendency toward rising pH before full phenolic maturity, Mencía frequently requires acid adjustment, either through direct additions of tartaric acid or through blending with higher-acid indigenous varieties. While it’s reliable, productive, and capable of very good wine, it rarely carries the emotional currency I look for. Mencía can be complex, yes—but complexity alone isn’t always enough. It’s a fabulous by-the-glass wine, one of the best for price and quality, in fact; but beyond that (with a few exceptions, like our very own Pedro Méndez’s Viruxe at 11% alcohol grown just three miles from the Atlantic, or the ancient-vine wines made by the top Ribeira Sacra growers), I spend my Galician red wine budget elsewhere, given the alternative red expressions Galicia has to offer. I have deep respect for the growers committed to Mencía, even when the wines they produce, however well made, do not resonate with me in the same way as other Galician red varieties.

You may think I’m scoring an own goal here, or kneecapping Xabi and five other growers we work with who have Mencía in their range, but I’m not. I’m being honest about this. Their Mencías are fantastic, and Xabi’s 2022 version is impressive and by far the best one he’s ever made. Mencía’s game is strong here, but it’s Division Two. What matters most at Pradio is Pacio, a wine built from a blend of the four principal indigenous (if one can truly call them that) varieties of the area, Division One. These are all naturally high-acid varieties, all highly aromatic, and they represent the deeper historical and viticultural truth of this place. They’ve been here for centuries. Mencía functioned as a stand-in workhorse variety, valued for its reliability and approachability, and for offering access to a broader, volume-driven market; it can also be very elegant and easy to drink. When it first arrived in Galicia, it was a savior for a wine industry that had largely abandoned Ribeira Sacra altogether. But it’s not the queen or the king—it should be viewed as a steward awaiting the true return of these varieties, which were mostly abandoned because there was less of a guarantee for a crop from them in those days.

The ancient varieties I speak of are fine, definitive, world-class, and authentic, with a potential for emotional currency that feels effectively limitless. This is the currency that shapes my daily choices in the wines I drink. The challenge is that mildew, successive wars, industrialization, and the political regime that suppressed continuity for generations broke the line—information lost, destroyed, and mostly forgotten. Indeed, they’re not easy to grow; they’re like Burgundy and Jura varieties: fickle, sensitive, and easy to lose volume to medium-sized weather events. Yet here the high-end wine world remains overly fixated on Mencía.

Imagine Burgundy and Jura had the same broken line of passed-down knowledge and were replanted with Merlot, Syrah, and Sauvignon Blanc after the great wars because they were easier, more productive, and more profitable than Pinot Noir, Chardonnay, Trousseau, Poulsard, and Savagnin. Imagine if the world came to believe those varieties defined Burgundy and Jura, while the growers themselves quietly understood they were only caretakers, waiting for the market’s interest to return to the varieties capable of producing each region’s highest expressions.

First, there is Caíño (of which there are many bearing the name Longo, da Terra, Bravo, and others), a remarkably flexible lead that has not yet found the right voice to deliver this extraordinary character’s monologue. It’s extremely high in acidity, with medium to high tannin and relatively soft color, depending on harvest timing. It can be picked early and still taste phenologically ripe. It can also be picked later and become more rustic while remaining phenologically balanced and deeply complex. Among the varieties discussed here, I believe it holds the greatest potential.

Then there is the queen: Brancellao. Brancellao is very light and very pale—comparable to Poulsard or Premetta but with racier acidity. It has a very light phenolic profile and extremely pale color—almost rosé-like. Caíño Longo and Brancellao, in general, produce more red fruit, unless the Caíño is picked later, when it remains red but moves more toward earth and rusticity than toward fruits and flowers.

Next is Merenzao, also known as Trousseau. This brings a more purple tonal range and very exotic aromatics—violets, Persian mulberry, that spectrum. It’s aromatically charged and hard to ignore its prettiness. But I’ve often noted that Trousseau as a single variety in both Galicia and Jura often has strong high and low tones but a hollower center.

Once you arrive at Sousón, you’re dealing with a very dark grape—a black grape. After just a few hours of extraction, it develops massive color, and the further you go, the blacker and inkier it becomes. Sousón is a wolf that makes Syrah look like a house dog. Massive acidity, massive tannin, massive color—but it’s not innately corpulent; the regional igneous and metamorphic soils, well-drained and acidic, keep it lean and tight, like Daniel Day-Lewis’s sinewy but muscular frame as Daniel Plainview or Bill the Butcher. In Portugal, this grape is known as Vinhão, and it has historically played a foundational role in the wines of the northwest.

(Notably missing here is the variety Espadeiro, which, while one of Galicia’s most talented indigenous grapes, last I heard, it’s not permitted in wines under the Ribeira Sacra DO.)

Backstory Opportunity

In northern Portugal and Galicia, when Britain was cut off from French wine—most notably during the long cycles of Anglo-French conflict—drinkers didn’t wait politely for Bordeaux to return in its truest form. They drank what arrived. Many were supplemented with wines from northwestern Iberia: darker, firmer, higher in acid, and stable enough to travel, with freakishly low pH levels.

Export volumes of Portuguese wines (including from the northwest) increased when French supply was disrupted, especially during 17th- and 18th-century embargoes, and again when phylloxera decimated French vineyards in the 19th century.

Later, during the phylloxera outbreak, a convenient mythology emerged that regions like Cornas, Hermitage, and Côte-Rôtie propped up Bordeaux during its collapse. It’s likely true to some degree, but does the math work? Can the land in the area support such a claim? Does a rise in production there fit the timeline? It’s hard to tell.

Stability, firmness, and structural authority were desirable traits in wines, and northwestern Iberian varieties already spoke that language, especially Vinhão (PT)/Sousón (ES). Portuguese winegrowers with a knack for history will tell you that substantial volumes of wine were exported from Galicia and northern Portugal during these periods, not as replacements for Bordeaux, but to contribute to the demand when French supply faltered. Without solutions yet for phylloxera, Bordeaux at that time would’ve needed large volumes of structurally sound wine that could move cheaply and quickly, and northern Portugal already had the infrastructure to do exactly that: rivers feeding ports, and ports feeding the Atlantic straight into Bordeaux. By contrast, the northern Rhône was small in production and would be logistically awkward, requiring slow, expensive overland transport or southbound river routes that made large-scale diversion unrealistic.

And that demand rewarded certain grapes. Sousón, the same grape as Vinhão and by far the most dominant red variety in northern Vinho Verde just across the border from Galicia, rose to prominence. I have Vinhão at my home in Ponte de Lima, and the fifteen-minute drive from town to our front gates is like a canalized river held in place by vine-stitched rock walls and massive Vinhão and Loureiro canopies the whole way. Sousón/Vinhão is capable of delivering color, acid, and tensile strength along with big volumes in hostile conditions. Vineyards were replanted in northwest Iberia accordingly, not out of ideology, but out of survival and usefulness. Vinhão wasn’t invasive; it was propagated in its historical home.

If a maker wants it, this grape can carry the entire frame of a wine—the pelvis, the shoulders, the legs. Everything structural. That’s not an accident of history. That’s why Vinhão endured in northern Vinho Verde over all its redder siblings. The only things it seems to run short on are redness and gentleness.

Back to the Miño

That said, Pacio is not built on Sousón; there is only a small amount of this powerful wine in the blend. The majority is Merenzao, Caíño Longo, and Brancellao, with a touch of Mencía and Sousón. That choice shows clearly in the wine and results in something more regionally and historically authentic with respect to pre-World War times. I won’t deny that Mencía transmits terroir quite well; that’s not the problem. The issue is range. Even when it’s grown on great sites, it tends to tell the story in a fairly narrow register, and after a while, that sameness can feel limiting. That’s a misrepresentation of what this region is capable of expressing at its highest level.

Mencía was widely planted for its consistency. This wasn’t about garage winemaking or passion projects. It was about survival. Growers needed a grape that wouldn’t fail them after a full season of work. These ancient varieties are more sensitive and require much greater intuition and attention to farm successfully. And that is precisely what makes Pacio so special.

Is there any truly great wine that was meant to be sipped like a cocktail? Is there any truly great wine that doesn’t match well with food? And it makes me wonder that if a wine is really designed to be enjoyed on its own, how well does it actually work once food shows up?

Some wines demand to be served with a meal, and they have their place, an environment where they fit. They’re wines of ceremony, wines of context. And some wines are not meant to be tasted; they’re meant to be drunk, they’re meant to be enjoyed while complementing richly flavored food. This is what Pacio is all about.

Ribeira Sacra Pit Stop | Restaurante Valilongo

Restaurante Valilongo sits inside a long valley on a very straight road between Castro Caldelas and Ourense, which may seem unusual for these parts, but it’s outside of the gorge of all the various winding rivers. Inside, people stare like cows in a pasture as you pass by; strangers in a strange land. The place is rustic—a cowboy saloon merged with a pirate dwelling with a deceivingly dull exterior. The guy who runs the front seems to size you up like he’s ready to take you to the table and skin you, but he’s super nice; so is his service team.

The first time there, I could read my wife’s mind: “The places you bring me …” We were joining Pablo Soldavini for lunch, and he swore this is the best spot around. The air is thick with the smell and feel of collagen, and you can imagine huge cauldrons of stews in the back, animal parts cooking with garbanzos, tomato, and potatoes. Caldo galego is ever-present, a chunky green soup made mostly of grelos (turnip greens), potato, and almost certainly a bone broth of some sort. It doesn’t look appetizing for first timers, but it’s delicious and perfect for the bitter cold and wet that’s always around these parts. Then they present you with specials, on the spot, with everyone staring back and forth between the front man staring you down and you, seemingly everyone in the place waiting for your decision. I always choose the wrong thing. My wife is the smart one. She sticks with caldo galego and special orders bean or garbanzo stew with the parts, greased up with collagen.

That collagen in the air is likely from some form of Cocido Gallego, not quite like what’s in cassoulet, but more like a mirror of Emilia-Romagna’s boiled meat dish, bollito misto. There are all kinds of parts, and not just the meaty ones. Lick your lips, and they’re still coated with collagen, stuck to the surface, instead of how it’s injected in other parts of the world. My wife couldn’t believe the quality of their soup options. She is quite fond of the place, as am I. But I should always stick with the beans; they come with enough meat already, no need to order a plate of it afterward.

This is conceptually where these wines belong. Not in pirate bars and restaurants, but not necessarily with a Michelin-star tasting menu, either. For me, this wine really comes alive with grilled and braised meats and deeply savory food—that’s where it makes the most sense, and where it actually gets to be itself. Pacio will indeed suit up nicely for perfectly manicured plates designed to aesthetically wow with their architectural display. But it’s more comfortable and expressive with foods that could use a palate reset before the next mouthful of collagen-rich deliciousness.

And even still, without but a touch of Mencía, the older varieties that existed before Mencía’s invasion, Caíño Longo, Brancellao, Merenzao, and a touch of Sousón create a wine with incredibly intense but inviting natural acidity.

Metamorphic rock wall from the vineyard

A Pacio Experience

On January 22nd of this year, the wine started strong out of the gate. I remember tasting it last year at this time. It was brighter, the fruit was redder, the aromatics slightly more lifted. Now it has settled in. It’s deeper, and the color is still quite light for these parts—slightly tinted ruby. And for this blend of grape varieties, it’s just the right balance of taut freshness with a slight green note that works well.

I would still argue this is one of the very best Ribeira Sacra wines I’ve had. It’s incredibly pure. There’s a lot of joy here. It’s a breakthrough. That schisty, metallic strength you often find in wines like Côte-Rôtie is prominent, and it has Syrah-like greens but more bay leaf than thyme, more eucalyptus and wild forest than Rhône garrigue. This is not a pile of jewels overflowing off the top of a crown. It’s a massive metal crown with very finely etched jewels—pure, clean, sharply cut and elegantly set.

Sometimes, when I try to write tasting notes, it gets complicated because the wines are so fascinating that all the details get bottlenecked in my head. This is one of those times. It keeps pulling me back to the glass. It’s not really a wine to sit around and drink casually. It’s ceremonial and warrants occasion. As for how it compares to the previous years, the 2022 Pacio is on a different level. This is one of the coldest areas of Ribeira Sacra, farthest west before you pass through Ourense and into Ribeiro, and unlike other producers in the warmer zones (like those stunningly picturesque vistas of Amandi) where the fruit smell seems partially baked out, this wine retains fresh, wild fruit shaped by wind and cold influence. The vineyard sits on a very active stretch of river by comparison to Amandi, for example. You feel the mist, the forest air, the depth, the cold, the wet rocks, the hustling river. You feel this current moving past the vines every day, even on the hottest days.