The Source was always about dreams. I grew up in northwest Montana—not exactly a wine mecca—and I didn’t touch alcohol until I was nineteen. It was a Guinness, illegally poured for me in a restaurant with fellow waiters from work. I’d just moved to Arizona and interviewed well enough for a job waiting tables that I wasn’t qualified for, but Theresa, my future boss, was from Montana, too. I know that played a big part. But maybe the dreamer she saw inside me nudged her just enough to take a chance. Little did either of us know that the interview would lead to the pivot of a lifetime—my north star was locked in.

My beginnings were humble, but they were safe. We grew up in a strongly religious family, and we were mostly outsiders in school—not Witnesses or Seventh Day, but not far from them. In the same way I’ve manically studied wine for decades, I used to study The Book like crazy to understand why I should believe what I was told to believe. Then, I hit high school and began, as they might say, to stray from the flock. A new religion fell into my lap when Theresa hired me, and I found a new deity and mythology, a new camino, a new source.

I used to dream of having dreams, but my direction was all over the place–other than when I was playing sports. I was a decent student at best; partly to blame were my ADD tendencies, vacillating between extreme focus and complete attention chaos. I was solid in Math, Science, Art, History, and, miraculously, English. Like the first orthotic insert at twelve that straightened my slightly crooked spine, wine did the same for my meandering goals of getting out into the world—falling in love with life, and the idea of travel, adventure, and deeply different cultural experiences. I didn’t know where I was going, but I knew my eternal travel companions would be my dreams.

But I never even dreamed of being where I sit right now in Spain overlooking the narrow crossroads of the carrers of Sant Pere and Estret below, bleeding my thoughts and self-discovery while in Catalonia into a newsletter centered on the growers themselves as much as their wines, published for all to read—to criticize, to write off, or, hopefully, to appreciate and encourage me to continue sharing the strange and beautiful rollercoaster I got on and have kept riding all these years.

Never a Jack Kerouac, always more of a Lewis and Clark type: Alone we go faster, together we go further. I played team sports—basketball, volleyball and playground football. When we weren’t playing games together, my older brothers ran off into the forest to build forts to fend off neighboring invaders and dig holes toward China, leaving me with my younger sister, Victoria, whom many of you know as the superglue of our company and one of the two people with feet firmly planted on the ground, holding the strings attached to the kite that is me; the other being my wife.

“If I have seen further, it is by standing on the shoulders of giants.”

– Isaac Newton

In that sense, I’ve been very lucky in life, but as my late Provençal friend Pierre Castel said while giving me a tour of the low and rocky limestone Alpilles just south of his home near Saint-Rémy de Provence, “La chance est un cheval au galop, il faut courir pour l’attraper.” (“Luck is like a galloping horse; you have to run to catch it.”)

This is why I love what The Source stands for. We don’t always pursue those who sit at the tasting table and ask what we can do for them, though on a rare occasion, we may. We prefer to sit at the table of fellow kites who need some extra string held by people whose boots are on the ground. What are their dreams? Where do they want to go? What do they want out of this? Do we fit for the full haul of a life’s journey in wine together?

If this were about money, I would’ve forsaken so many growers that made mistakes on my dime and walked away at the first sign of trouble. No—that’s a wine merchant, not my view of what it is to be an importer. The best wine importers are messengers, couriers for their clients and their growers. Involved importers can effect true change, not only by taste-making but by making believers out of the skeptical or uninformed.

Dionisis bless ‘em, so many have taken a chance on me, and without those people, I wouldn’t have stood a chance on my faith alone. (There were far more detractors than believers—believe me, and there are still surely plenty.) We are believers and supporters of the dream—measured risk takers, a company that uses its hard-earned platform to bring the unknown and humble heroes to light, the dreamers who need a believer to take a chance on them, those who need a louder voice to prop up their ideas for them—sometimes to push them from the tree they nest in, viewing the world below but not ready to take the leap on their own.

Christopher Nolan’s movie, Inception, inspires me and even emboldens my narrative when it comes to igniting the fires. In life, we cannot change people by directly telling them how to change. But we can plant seeds. Dreams can’t be forced, but maybe someone can be reminded that the world invites them; they only have to walk through the door. That’s what was needed for the first of the two growers in the upcoming sections of this piece. Not direction. Not correction. Just belief in them at the right moment, planted carefully and methodically enough to take root.

Belief is not always a grand act, but it can scale psychological mountains. It’s also transferable, and sometimes all it takes is one thought. Suddenly, something clicks, a flicker reigniting the inner child, the forgotten dreamer. My wife warns me to be more careful when filling people’s heads with dreams: “But are they your dreams for them, or theirs?” When my enthusiasm for the company rises, I sometimes feel her psychological reins tightening to keep me in check. The spark that lights my fire for the person across from me is never premeditated. It’s natural, not an attempt to persuade or direct, but to remind. This is how my mind moves. I think of A.D.D. as Attentional Divergence Dynamic, not a deficit disorder; it’s now understood that for some, it’s a different kind of advantage. It’s my calling—not to lead, but to suggest that the dream can be more than just a dream.

Fabrice Esnault | Domaine la Giraudière

Brézé & Saumur-Champigny

Available From the Source in all U.S. states

Sometime in 2021, Arnaud Lambert gave me a name. I wanted, needed, a new grower in Brézé to work with across the US. Brézé hadn’t yet begun its renaissance when we first imported Arnaud’s Château de Brézé wines from the 2010, nearly two years before Romain Guiberteau’s wines shocked the wine world. I knew Brézé was special from the starter wines I tasted from Arnaud and his late father, Yves, from the hill in their first years there in 2009 and 2010 after signing a 25-year lease on the house and property. Masterpieces? No, not yet. But their straightforward handling (and in a much smaller part at the time, organic conversion) allowed the breed of this decades-long chemically abused world-class terroir to rise despite their birthplace, with the only living thing, the vines themselves. It was obvious that there was something unusual about the wines—something that evoked the same feeling of discovery I felt in my first years, only this time I was much more experienced and better equipped to know the difference between clever cellar manipulation and the innate architecture of a great terroir waiting for the right smithy.

The Source has been heavily associated with Brézé since the beginning of our company. When we decided to cast our net from California across the country to New York, covering many states in between, it was strange to be missing wines from Brézé, perhaps the greatest cornerstone of our earliest identity as an importer. That’s when Arnaud suggested that I meet Fabrice Esnault. “If you can help him believe like you helped me believe even more in myself when we first met …” There is no greater pleasure in my life, no fuller satisfaction I get than to contribute inspiration when someone just needs that little push … Inception.

Nostalgia—that’s the best way to describe my first tastes of Fabrice’s Chenin Blanc from Brézé. With Arnaud standing next to me and Fabrice in Fabrice’s Van Gogh-like, cramped and dimly lit former public tasting room—shiners, label rolls, old bottles forever on display and never meant to be opened perched on a shelf above his reflective head and darting blue eyes, it was indeed déjà vu: 2010 all over again, Brézé, Arnaud—the thrill.

In Plain View

For nearly two decades after Brézé rose to become the wine world’s newest darling of Loire Valley Chenin, Fabrice’s family domaine name sat in plain sight: a hundred meters north of Château de Brézé’s south gate, written in large Burgundy-red apothecary script pasted over pale yellowish-gray and the white tuffeau limestone blocks of their tasting room: Domaine la Giraudière. Above, to the right, in small font: Saumur Champigny, and below, Vins de Brézé—the latter seemingly positioned deferentially, still second fiddle to the greater public; a distant fourth to the celebrated reds of Saumur-Champigny and the sticky and dry Chenin Blanc of Anjou. The arrangement of hierarchy? A misunderstanding? Well, perhaps a lapse of historical amnesia.

While the sign was impossible for any importer to miss, names like Clos Rougeard, Collier, Guiberteau, and Lambert tend to cloud the vision. Everyone missed it, including us. But in 2022, after an inquiry the prior year about other potential growers on the hill, having passed the sign countless times while jogging off the foie gras, bread, and cheese from Arnaud’s, or meandering through the commune seemingly empty of any other promising growers that could rival the “big four,” Arnaud walked me into Fabrice’s cellar.

On this hill, which I once called the greatest forgotten hill—the Château de Brézé, long before the arrival of widespread chemical farming after World War II, recorded exchanges of its Chenin Blanc from its tuffeau limestone-rich soil with those of the world’s most celebrated domaines and châteaux, including the inimitable Château d’Yquem. Fabrice is yet another newcomer of sorts to the now internationally acclaimed Brézé. This commune sparked a makeover of dry-style Loire Valley Chenin Blanc and brought global attention to the expansive Saumur appellation.

Better Late Than Next Gen

Some importers like to zero in on well-established growers, or those prematurely anointed as “the next rising star” by social media wine ideologues, too early on in their process. To contribute to the rise of an unknown who quietly shows greater promise—and with quality terroirs to match—than what’s been put to bottle brings great meaning to this importer, also a greater sense of accomplishment and camaraderie.

Before our first visit with Fabrice, Arnaud described him as a hard-working vigneron with a special level of skill and intuition in the vines. But the first tastes of his young 2021 Chenin revealed that we were just on the first page of what will be a long and rewarding tale of a late bloomer in one of the great terroirs in France.

Fabrice is a third-generation grower, built for the trade (and like a former rugby player), who looks like he could shoulder-press a mule or handle himself just fine in a lumberyard rumble. Following in his father’s footsteps, he spent most of his working life doing the hard things first: farming, fixing, lifting, and pruning in freezing temperatures—then sending the bulk of his fruit to négociants and a modest share saved for his tasting room. But appearances can be deceiving. Behind the strong physical presence, he’s timid yet open. He even appears surprised by compliments to his wines. But once he opens up, he’s warm, and his eyes twinkle as he smiles and speaks of his work.

It was one of those cold spring mornings in the completely exposed and windy Saumur landscape, the vineyard’s thawing frost condensing inside my boots, moving up through my body and out of my skin, keeping me cold to the bone. After we visited one of his vineyards, we had a cellar tasting out of barrels, vats and bottles, and it became crystal clear that Fabrice had more than just a talent for the vineyards.

Though his talent in the vines is obvious to his colleagues, his potential in the cellar may have been hidden even from himself.

The style has always been simple, clean, unadorned—a perfect test of whether a terroir has the mettle to elbow to the top of the podium. But it was a foregone conclusion. Given his vineyards inside Brézé and Saumur-Champigny, all that was needed was to taste one hit on his humble eight-track to be sure that Fabrice had more in the tank than easy price point layups from vintage to vintage for tourists on their way to the château next door. There was more than a single hit, but one of the group would be an obvious win for anyone familiar with the magic of Brézé.

The standout was a wine that will soon carry the label, Chenin Terrage, which perfectly reflected its terroir in crystalline clarity. It was also much more accessible than the typical zippy and forceful style of a Brézé wine. It also came with a price tag that seemed to have been carried over from his father’s days before Brézé even became a “thing.” It was Fabrice’s first organic cuvée, harvested from a parcel just 200 meters northwest of the cellar. Most revealing was that, even if the wines weren’t yet at the level to compete with the big four and the other great Chenin of the region, the whites showed clarity and promise. Chenin Terrage (labeled simply Saumur Chenin) demonstrated that Fabrice would indeed find his own path with the entire range, and one day, likely stand tall next to the big four and maybe even move up those ranks.

The reds were solid enough, if not solid values, at the start. He was a little deep on vintages, so most of the wines initially tasted were from about two or three vintages older than what was typically on the market at the time for short élevage wines. They still showed promise and are from areas of Saumur-Champigny that highlight elegance over power. Like the whites, they were crafted directly and simply—no new wood in the way, and no funk either. Aromatic lift and palate tension lead the way.

Both Saumur-Champigny cuvées were a step up from the younger vintages I tasted a few years earlier. As he continues to refine his cellar work, perhaps simply by having enough market interest to bottle earlier and all at once, the uptick is inevitable. His two vineyards of Saumur-Champigny are adjacent but different, with Les Meuniers, on shallow limestone-clay soils atop tuffeau bedrock, and Les Chauvelière, on sand and gravel with less direct tuffeau contact—only meters apart but seemingly a world away by Loire Cabernet Franc standards.

The potential? No limit. Though his talent and know-how in the vines are obvious to his colleagues, his potential in the cellar may have been hidden even from himself. His most promising aspect is his practicality, which diminishes the possibility that he’ll get in his own way during his rise. All that was needed was that nudge, some confidence, encouragement, and a commitment: a guarantee to buy should he produce more for us to export to the US. And, Arnaud and I were there to give it.

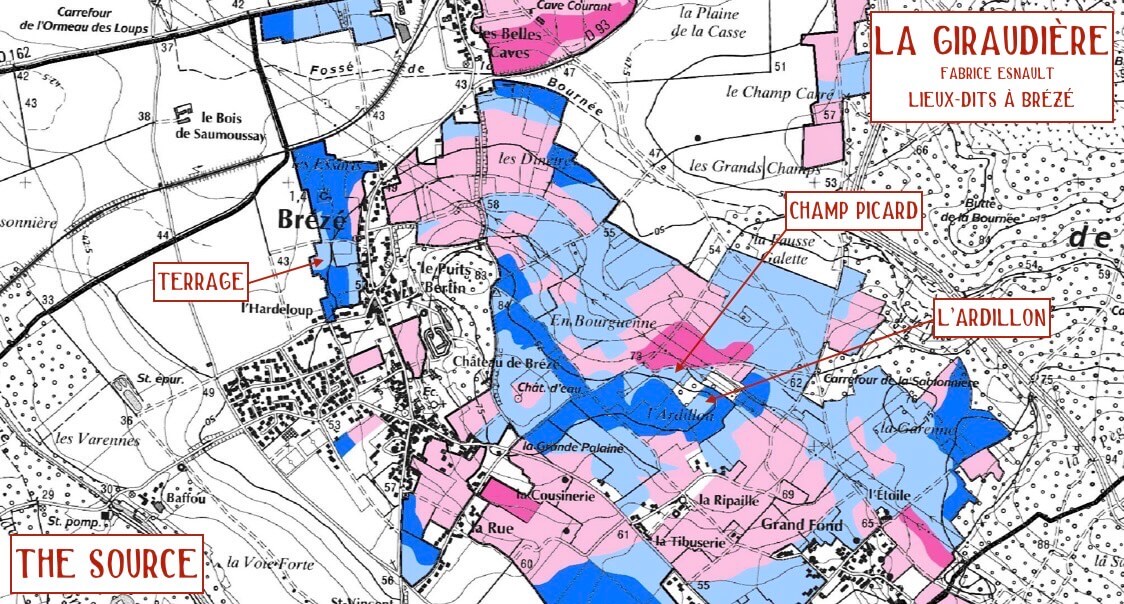

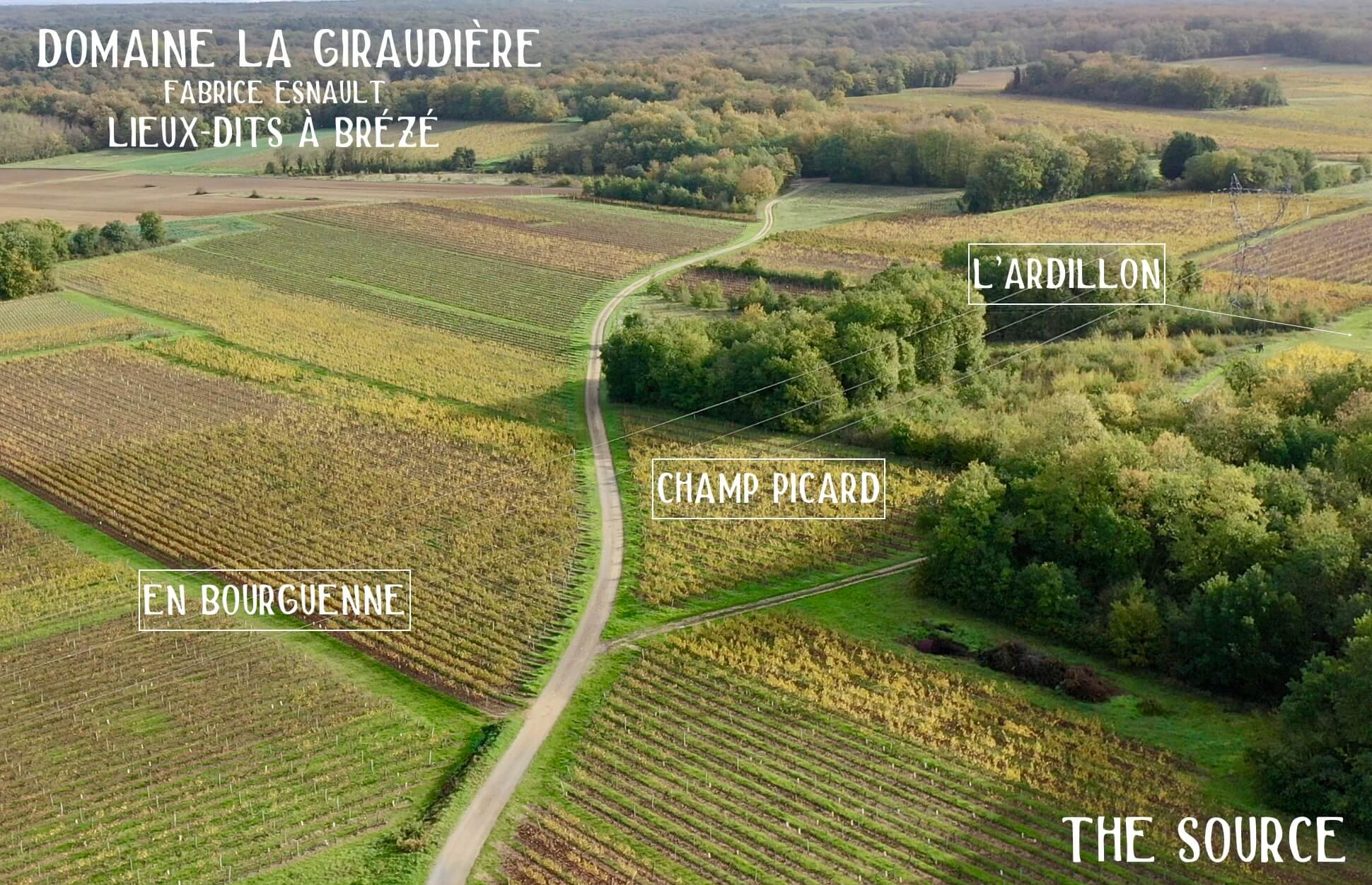

A Solid Stable

Fabrice farms more than twenty hectares across Saumur-Champigny’s Montsoreau and Turquant and the vast Saumur appellation’s crown, Brézé. His farming technique is careful, sustainable, and trending toward organic across key parcels first. L’Ardillon, a relatively large lieu-dit just above another expansive lieu-dit, en Bourguenne (home to some old-vine parcels of Clos Rougeard and Guiberteau, and Lambert’s unicorn cuvée, “Brézé”), is set to lead Fabrice’s charge. A notable difference between these two lieux-dits has as much to do with temperature as soil. Both are richer in clay—shouldery wines—with Bourguenne warmer and fully exposed to the environment, while l’Ardillon (and another of Fabrice’s parcellaire wines inside of l’Ardillon, Champ Picard) abuts tree groves on two sides, and the temperatures are notably fresher. L’Ardillon’s vines average thirty-five years old, and the elders are around seventy-five.

The cellar logic mirrors that of his vineyards: preserve fruit and place, sculpt when needed, and avoid the trickery that turns terroir into house style. The more clay-rich sites, such as l’Ardillon, are crafted in wood, while others in sandier, loamier soils are in larger neutral vats.

Small, unexpected moments often say a lot. One such moment was in the cellar in November 2024. There was an unlabeled emerald-green bottle—a personal favorite color of mine for bottles—with a crusty, aged cream-colored wax top, and its old cork forced partially back in and a third of the liquid remaining. A Chenin from Brézé made by Fabrice’s father in the 1990s, it poured the color of platinum, moved like a wine a tenth of its age, and tasted like it was worth two hundred times its likely release price—the first tastes seemed otherworldly. The dregs of that bottle were gorgeous, but Fabrice insisted on opening another. It was another capture of the sublime—a timeless wine; a wine of place that could’ve been from any of Europe’s great growers. It was as thrilling as a perfectly aged Vatan Sancerre, Müller Kabinett or Alzinger Federspiel Riesling, a hint of a Meursault only kissed by the vigneron in the cellar, and not much more. Perhaps it was the most stunning two-bottle showing of any white wine I’ve had from Brézé. Unadulterated purity—that’s the target: work well in the vineyard and let the terroir (if it’s a formidable one!) do the heavy lifting. This is what I love about Fabrice’s style. He’s already in that line—relatively tinker-free. That’s why I’m as drawn to him as much as any Chenin grower’s wines from Brézé—or any other hill growing high-quality Chenin, for that matter.

What seems clear about white wines from this tuffeau-rich hill and similar ones farther south in Saumur (in my opinion) is that those who harvest from vines grown on sandier soils and with more direct contact to the tuffeau bedrock express greater fluidity in more neutral vessels, like old oak barrels, concrete, or fiberglass. With a richer clay topsoil, like those in Bourguenne and l’Ardillon, they need a little help sculpting their muscular frame—old wood is the right medium, though not for spice rack flavors of new oak that some view as increased complexity, but solely for the micro-oxygenation effect; to massage and unfurl the wine and allow its geological genetics to bloom. Perhaps it was a function of costs from his limited ability to commercialize his wine on a greater scale, but when you have such magnificent talent as this noble grape on this noble bedrock, less is indeed more. Those two old bottles from the 90s made by his father would blow anyone’s mind; it was an unforgettable experience—a testament to Brézé, simple and direct vineyard and cellar work—a capture of a wine’s truth!

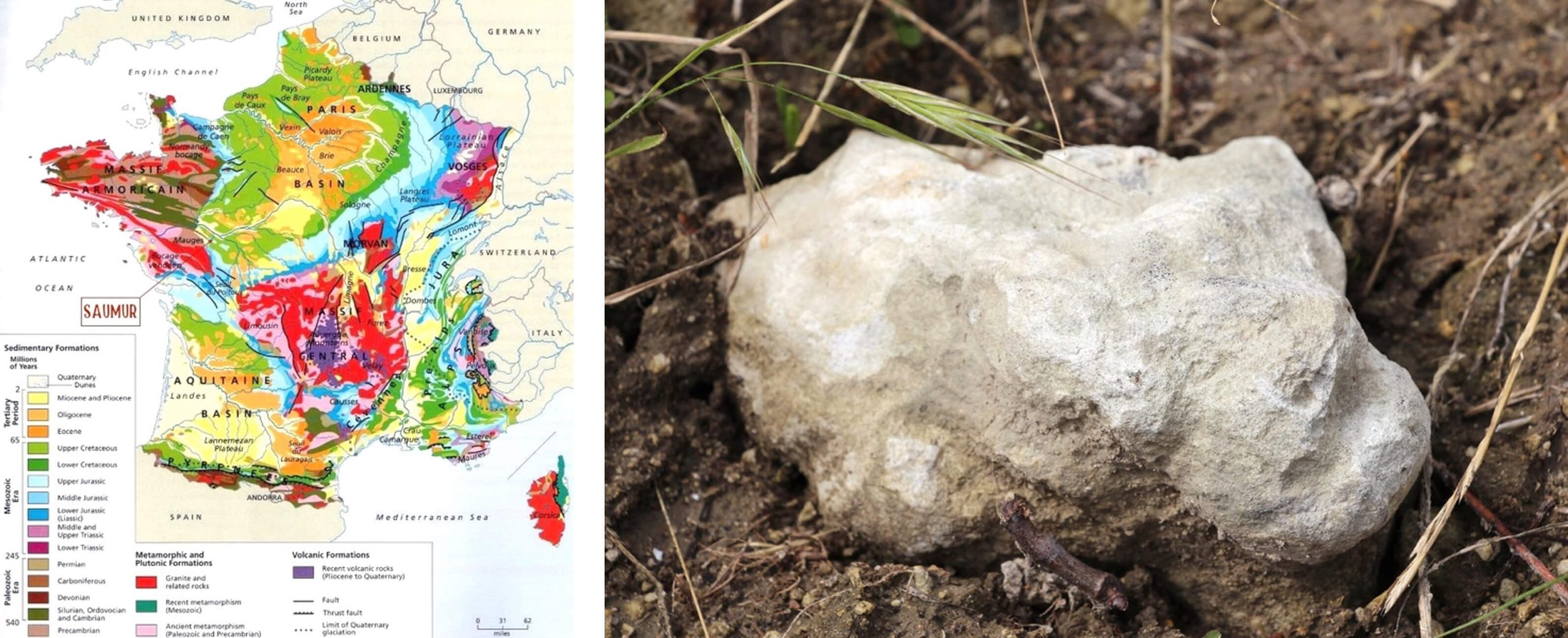

Macro | Micro

Saumur sits on the southwestern rim of the Paris Basin, a broad, saucer-shaped, calcium-carbonate-rich sedimentary bowl with concentric rings: older Jurassic strata below, younger Cretaceous strata above, and on and on. Saumur’s signature bedrock, tuffeau, arrived in the Upper Cretaceous (Turonian), when a warm, shallow, tropical sea thrived in this flank of the basin. For millions of years, the water teemed with hundreds of trillions of tiny creatures whose carbonate-rich micro-skeletons settled into lime-rich muds while fine sands washed in from the weathered heights of the Massif Armoricain to the west, and in later ages, from the Loire River’s origin in the acidic soils of the Massif Central that deposited much of the lower areas of the region.

Tuffeau is pale, fine-grained, and unusually porous for a rock often used for building (in all the white castles, churches, and residences of the Loire Valley!), usually composed of around 80% calcium carbonate with a notable fraction of micaceous sands (muscovite) that glint in the light and are easily visible with a geologist’s handheld loupe. Low cementation renders it lightweight in the hand—and that lightness translates in the glass: Chenin that’s lifted and tensile; Cabernet Franc that’s vivid and clear rather than burly and chewy.

Saumur also has a unique climate among other viticultural areas of the Loire Valley. It lives in the rain shadow (the lee side) of the Massif Armoricain to the west. Westerlies off the Atlantic shed much of their water over Brittany’s uplands, and by the time they slide into this area of the Loire trench, they’re drier and steadier.

Fabrice’s Saumur-Champigny vineyards

Fabrice’s Saumur-Champigny vineyards in Montsoreau and Turquant are in the far northeast of the appellation, up on the plateau above the Loire. Set farther away from most of the river and near the dense forests to the south, Brézé’s elevated exposures of east/west and north/south slopes, open to moving air, fend off rot and keep nights cool. The Loire itself is a long, shallow radiator, but about a twenty-minute drive north from the hill. Maritime influence without the deluge, a longer runway into autumn, and enough diurnal range to lock in acidity, it’s no mystery why Brézé’s whites have been prized for centuries: the hill is built for them.

Contextual Sidetrack | The Brézé-Rougeard Effect

It is worth pausing here to touch on the irony of Saumur-Champigny’s most famous estate and the rise of Brézé. For years, Clos Rougeard occupied a perfectly ordinary corner of top U.S. wine shops—always there, seemingly by categorical obligation, usually slow to move, rarely spoken of with awe—more often criticized for its variability and perceived meanness when young. Then, almost overnight, the market turned. Rougeard was no longer the steady stalwart of the Saumur section but Saumur-Champigny’s lightning rod of global collector desire. The shift was as abrupt as it was total. Bottles once stacked quietly in retailers’ back rooms or out in the open on the floor (the same could be said for the Rhône Valley’s Allemand and Jamet around the same time) were suddenly being traded like securities, both financially and as the perception of credibility on social media platforms, accompanied by a mystique that rewrote the narrative of the entire appellation.

The problem, of course, was the inevitable narrowing of vision. The gravitational pull of Rougeard nearly collapsed the diversity of the appellation into a single identity dedicated to the wine-centric restaurant world. Some buyers seemed satisfied to let this one domaine stand for the whole, while dozens of excellent growers worked in relative obscurity, or were relegated to great by-the-glass options. There are exceptions today—Fosse-Sèche, La Porte Saint Jean, to name only a few that frequent lists and shelves—of course, but fewer than there should be.

At the same time, Brézé was mounting its conquest—not of red, but of Chenin Blanc; its leading domaines: Guiberteau, Collier, Arnaud Lambert, and Clos Rougeard through Saumur Blanc in addition to their Saumur red from Brézé. And while Chenin was the spearhead, the reds of these growers also found their way onto lists. They were scarce, yes, but scarcity was part of the draw, and soon many serious wine programs had them. The effect was real: Brézé’s rise, even in red, wedged out opportunities for other Saumur-Champigny growers, whose production volumes and overall presence far exceeded Brézé’s before but whose visibility largely became eclipsed.

Overlay this with a broader cultural shift in taste. For many decades, Chinon seemed to be the central appellation of Loire Cabernet Franc, its stature elevated by Pierre Breton and Charles Joguet and the narrative eloquently spun through Kermit Lynch’s pen—they were, at the time, among the most prolific Loire Valley Cabernet Franc growers included among the top wine programs in the US. But as we entered the 2010s, the spotlight began to shift west, toward Saumur-Champigny, where the domination of tuffeau bedrock with deeper clay-rich topsoil along the same river, but higher up on bluffs, whose air made wines that seemed already tailored for the modern palate: brighter, higher-toned, and with the chalky figure of tuffeau that seems to translate through to the palate, staining it with a strong minerally sensation more than a tannic residue.

This is the paradox. At the very moment the broader style of Saumur-Champigny began to tailor itself to the market’s ideal of lighter, perfumed, and precise wines, the appellation’s visibility was all but closed off from view, at least in many parts of the US; there didn’t seem to be any Saumur-Champigny worth posting on social media if the label didn’t read Clos Rougeard. The result was a distorted map of the Loire: a few exalted producers and sites glowing brightly, while the wider, richer field of growers and terroirs remained more on the sidelines. There’s too much talent in the Loire Valley’s main Cabernet Franc areas—Saumur-Champigny, Saumur, Bourgueil, and Chinon—to have them largely typecast as value wines beyond Rougeard’s cult and Brézé’s rise. Isn’t it time for this to change?

One of the main challenges, though, is that those made thoughtfully need more time in the bottle to demonstrate the depth of their merit and to show that they are indeed worthy of the highest praise. Rougeard has already done this for more than half a century, which means that any new contenders will have to do a lot of catching up to prove the theory.

What’s missing, aside from this time for the potentially great wines to develop in bottle, is also the incentive for growers in Saumur-Champigny to make better wines overall and to help the world learn about their appellation. Saumur-Champigny is ripe for the picking, and this is one of France’s behemoths waiting to be truly awakened. For a moment, it seemed to get into about third gear, but troubling times have turned back the clock, and most have regressed into value-oriented utility rather than a new and exciting headliner. The same is happening in other regions of decorated history, like Italy’s Alto Piemonte wines—at least at the time of this writing. To this wine lover, there isn’t a more promising category that offers widespread accessibility for lovers of French terroir than Loire Valley Cabernet Franc and Chenin Blanc. There isn’t a larger category of wine in the country that even remotely competes on price, quality and volume, and if they win in that category, there’s no reason their best terroirs won’t climb to the top of France’s podium.

Back to Fabrice

If the Brézé–Rougeard Effect compressed Saumur-Champigny and Saumur into a narrow club, the many growers like Fabrice Esnault may offer a way out of that cul-de-sac. In his case, he has vineyards in Montsoreau and Turquant—two communes on the edge of the Loire that were never terroirs that yesteryears’ critics lionized. For decades, reds from these villages were perceived as too sleek, too fine-boned to stand beside more muscular benchmarks of the western side of the appellation. Clos Rougeard, with its uncanny Grand Cru-like equilibrium, indeed stood apart.

But Rougeard notwithstanding, the hierarchy was clear: in a world judged by tastings more than drinking, power won. Elegance was relegated to by-the-glass placements or case-stacks. In Saumur-Champigny, Cabernet Franc has yet to find its Musigny beside its Clos de Béze-type (Clos Rougeard), but the possibility is there.

What’s more, Cabernet Franc, as its main red variety and the Loire’s location directly north of Bordeaux, was always subject to greater influence by Bordeaux’s inner workings and hierarchy, much more so than Burgundy. And the noise of power was always amplified by the use of newer oak and longer élevage times, which, in retrospect, seems to have relegated Loire Valley Cabernet Franc to always be the bridesmaid to the Bordeaux bride.

But perhaps that script is flipping. Even before 2010, many of the Côte d’Or’s most celebrated growers were still working hard to make their sales goals. Until around 2016 or 2017, we had a lot of inventory from top growers (Pierre Morey, Bruno Clair, Georges Noellat, Duband, and even Lamy before 2014) that was slow to move out the door. Even when in direct sales myself, running routes all over California, I had to put growers like Hubert Lamy and his 2011 vintage in the bag to show around Los Angeles. My business partner did the same in San Francisco, to engage people and prove that his humble center of Saint-Aubin was more than competitive and well worth the money. Then, that same switch that changed direction for Rougeard seems to have changed the entire Côte d’Or. Things began to sell feverishly, and various importers across the US were taking whatever Côte d’Or wines were around, no matter the quality.

Today, the measure of power in red wine is no longer extracted density or tannic wallop but the ability to hold intensity within a lighter frame. The greater Saumur-Champigny was slow to follow and is still further behind the cart than in front of it. The most celebrated wines now are more about finesse-led power than power-led finesse. Fabrice’s Cabernet Francs follow this line, and it’s his terroirs that lead his hand in the cellar. The tuffeau sand and river gravel of his Turquant parcel give his Saumur-Champigny “La Chauvelière” a soaring, perfumed register: violets, redcurrant, the chalk-dust, acidic snap and cool rock sensation on the palate driven by limestone. His Montsoreau Saumur-Champigny “Les Meuniers” with its greater share of clay limestone, adds weight without heaviness: black cherry and graphite carried on a taut, mineral spine. The result is a dialogue between lightness and drive, perfume and persistence, wines that feel full of flavor yet never burdened with too much weight or unnecessary matiére. Fabrice’s wines are nowhere near those of Rougeard and the region’s top domaines, but great terroirs speak just as loudly in inexpensive wines when respected and handled gently as they do with expensive ones.

Yet this is not the Loire Cabernet Franc of yesteryear but that of the now, and the elegance once seen as a limitation is suddenly the definition of strength. Fabrice’s reds do not need to compete with the cult bottlings of Brézé or the mystique of Rougeard; they succeed because they already express what many modern palates seek: tension, clarity, lift. And unlike the bottlings that became so rarefied they ceased to represent their appellation, Fabrice’s wines feel grounded in their place, generous without pretense, immediate and joyful, yet relatively age-worthy.

In short, Saumur-Champigny has been waiting for growers who can realign the conversation, who can show that the communes at the river’s edge—long overlooked in the search of a Bordeaux-like impact—are the natural bearers of a style the many should now prize. Fabrice Esnault will likely rise to be among those voices, and his wines are not simply part of Saumur-Champigny’s present; they are signposts for its future.

Back to Earth

Fabrice took his first step into organics before 2020 with what will soon be called Chenin “Terrage,” though labeled today as Saumur Blanc, or Chenin de Brézé. In 2024, after some proposals about how the wines could manage a slight increase in price with the potential of greater losses in the vineyards from organic farming and the extra labor without losing the market share that we were building, he made a bigger move to convert many of the parcels that constitute the wines that go through his tasting room as well as to the export market. With 20 hectares of vineyards, the majority still destined for the co-op, it doesn’t make financial sense to convert everything to organic until he builds a bigger market for the wines he bottles. What he receives from selling to the co-op is nickels on the dollar by comparison. But once he starts to pick up steam as the wines continue to improve, the confidence builds—not only for Fabrice, but also for the market. It looks like it’ll snowball.

His whites already express their origins with clarity and bring familiarity—salt, chalk, and a vibrating line carried by tuffeau’s porosity and Brézé’s long, cool glide into fall. The reds are honest to their terroirs: Turquant’s sand and gravel bring lift with juicy, earthy wines; Montsoreau’s clay topsoil and tuffeau bedrock provide spine, deeper mineral textures, tighter fruit; old vines used in Fabrice’s Marquisat Cabernet Franc on Brézé, bringing freshness, authority, and cool-climate depth compared to his Saumur-Champigny wines grown in slightly warmer areas. The label has changed; the cellar work has sharpened; the hill is doing what it has always done. It’s happening, but it will take time.

Cellar Notes | Chenin Blanc

Sparing in ornament and enological artifice, Fabrice’s latest renditions are pure expressions of some of the world’s most talented terroirs: Chenin Blanc from Brézé, and Saumur-Champigny of Montsoreau and Turquant.

The Chenin Blanc wines are pressed gently, kept cool, and fermented either in tank to preserve primary tension, or in old barrels to broaden texture without adding overt oak—few barrels in the cellar are younger than ten years. The split between tank and barrel is guided by site character: tanks to underline mineral line and snap, and old barrels where the clay-rich topsoil needs a little sculpting. The maximum fermentation temperature hovers around 17°C. No malolactic is preferred across the board, but if a barrel develops, it’s accepted rather than prevented. Sulfur is first added after vinification and again at bottling. All his whites are lightly filtered for clarity.

Fabrice’s Saumur-Brézé Blanc “Chenin Terrage,” currently with the 2022 and 2023 vintages arriving, is labeled a Chenin de Brézé or Saumur Blanc, was planted in 2018 at 48 meters altitude on a gentle east–west slope on the northwest side of the hill on deep rocky limestone and clay topsoil on tuffeau bedrock. Saumur-Brézé Blanc “Champ Picard,” which will hopefully arrive stateside just before summer, comes from Chenin Blanc planted in 1983 at 75 meters altitude on a gentle east–west slope inside the l’Ardillon lieu-dit, with deep clay, limestone and flint over tuffeau bedrock. This vineyard has a unique rock type that differs from any other vineyard Fabrice knows in the area, which has yet to be identified. And finally, the Saumur-Brézé “L’Ardillon de Brézé” was planted in 1985, 2003, and 2009, at an altitude of 75 meters, on gentle north–south and east–west exposures with deep clay, limestone and silex over tuffeau bedrock.

Terrage is the most elegant of the three with a strongly crystalline mouthfeel and aromatic purity—lines, angles, and as the French would say, aérien, meaning light, ethereal, literally “of the air.” Both l’Ardillon and Champ Picard are more muscular than Terrage and take longer to develop their aromatic profile upon opening. Fabrice considers Champ Picard to be his top site, and this is reflected in its price. These two tend toward a compact core and broad shoulders. The time in old wood loosens them up and rounds out their edging.

Cellar Notes | Cabernet Franc

All of Fabrice’s Cabernet Franc is destemmed and fermented in tank at a maximum temperature of around 21°C with gentle pumpovers (more frequent early, then tapering) to favor freshness over brawn. Élevage is in neutral large vats or old French oak, depending on the cuvée, so tannin feels fine-grained, and the soils do the talking. Sulfur additions are kept modest: post-fermentation and again at bottling. Filtration and/or fining only when the wine asks for it.

Saumur-Champigny “La Chauvelière” is in Turquant and was planted in 2005 at an altitude of 74 meters on a gentle north–south slope of deep sand and gravel over clay. Though Saumur-Champigny “Les Meuniers” is in Montsoreau right beside La Chauvelière, its topsoil is quite different. It was planted in 2001 at 72 meters on an east–west slope with a topsoil composed of about one-third fragmented tuffeau rock and two-thirds clay on tuffeau bedrock. Saumur-Brézé “Marquisat de Brézé” is harvested from 65-year-old vines at 80 meters in altitude on an east–west slope of deep calcareous clay on tuffeau bedrock.

Chauvelière reads as sand and gravel should: silky, perfumed, quick on its feet. Meuniers’ clay-limestone mix renders it more centered and classical. Marquisat, from old Brézé vines with extended maceration and old oak, shows the most depth and cadence without tipping into heaviness.

Arriving are the 2023 & 2024 Saumur Blanc, 2023 L’Ardillon & 2024 Saumur-Champigny “Les Meuniers.”

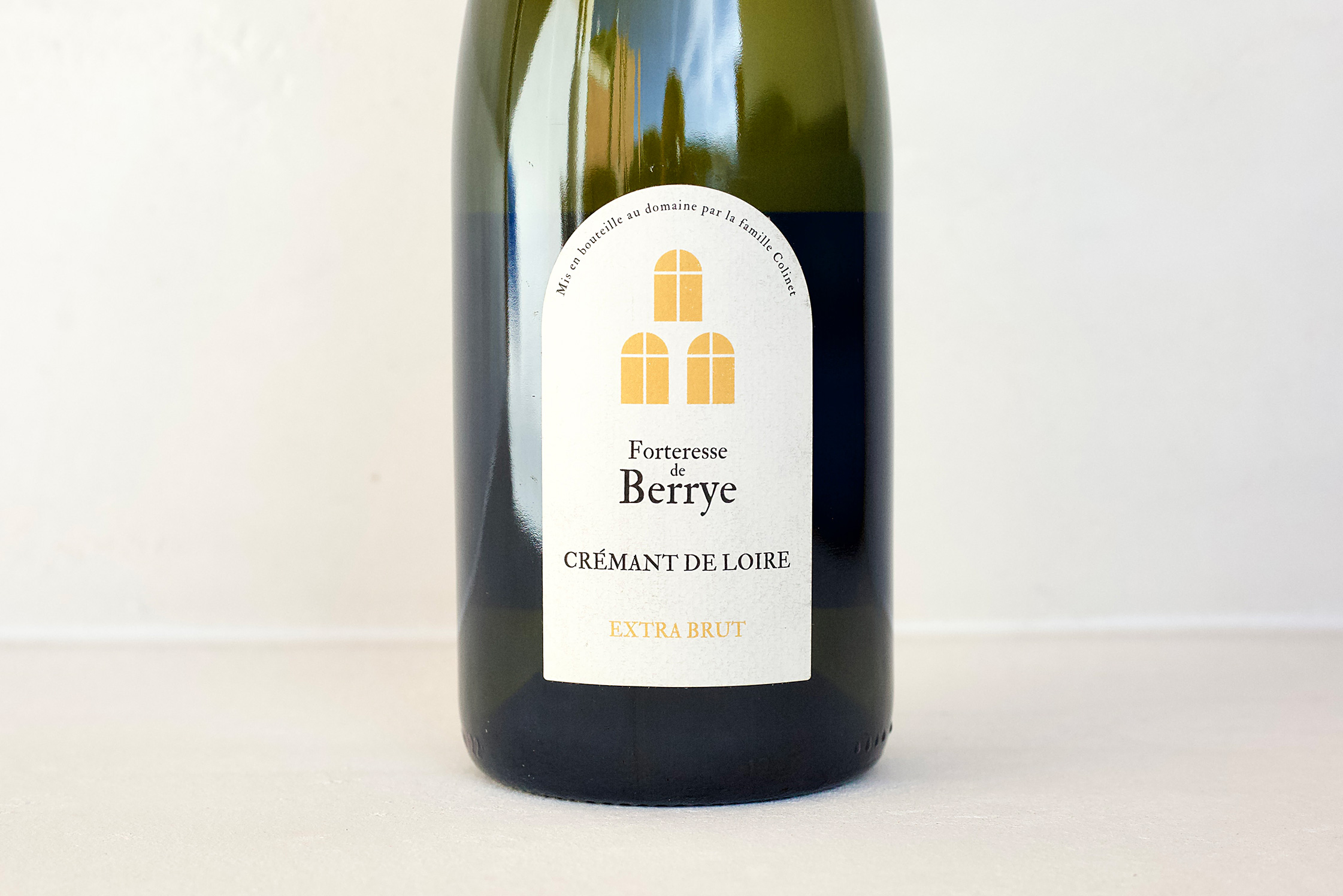

Gilles Colinet | Forteresse de Berrye

Saumur Puy-Notre-Dame

Available From the Source in all U.S. states

Fifteen minutes south of Fabrice, Forteresse de Berrye was also a leap of faith—a belief in terroir over all things, and an encouraging first contact with its new owner at the time in 2020, Gilles Colinet. The story was a simple one for me: Saumur is the next whale of discovery in the dry Chenin world. Brézé already sounded the alarm, but it cannot stop there.

The beginning of Chenin’s most recent dry wine renaissance took shape a decade and a half ago in Brézé. In 2011, Arnaud Lambert’s Brézé wines were on our company’s first container. Buyers couldn’t reconcile the electrical charge of his entry-level Saumur white under the Château de Brézé label, which was composed entirely of the historic Clos du Midi fruit at the time but not noted on the label. We had a hard time selling them, but nearly two years later, with Guiberteau’s wines in our bag for the first time anywhere in the US aside from his long-time Illinois importer, people took another look at those numerous pallets of Arnaud’s 2010s sitting in inventory, and we were off to the races. Even if our relationship remains good, our collaboration with Romain ended a few years ago due to our intermediary. But Arnaud, the quiet and largely uncredited spark that ignited the explosion of Brézé, remains a cornerstone of our California identity. So, where to go after Brézé?

When we extended our reach beyond the California border, it seemed that every tuffeau fragment of the Loire Valley had already been overturned. It wasn’t only picked over by other importers; sommeliers were also posting unknown growers on social media before they found representation in the US. This prompted many importers to follow those influencers with a wide reach and sprint to nab the grower. After the growers in Brézé attracted more interest in Saumur’s dry Chenin game, a mad dash of importers to the area was in full swing. We were once at the front of the line, but by the time we branched out, we found ourselves holding up the rear.

My original notion of being an importer was to seek out these nearly forgotten terroirs and the quiet, hidden talents tucked away in corners. If terroir is one’s guide, Puy-Notre-Dame and the tuffeau hills around are likely the next hot spot. Further south of Brézé, there are many hills just like it: tuffeau limestone outcrops that survived flood erosion and are separated by vast lowlands. That spark may be hidden within an imperfect, seemingly mundane wine that leads you in an unexpected direction.

That Guy Again

Our first lead on the area of Berrie (though the domaine name is spelled Berrye) came from none other than one of our Saumur heroes and most inspiring success stories, Arnaud Lambert, an unknown himself just fifteen years ago, who’s now world famous. Always interested in knowing if there was another area of Saumur with potential like Brézé before its inevitable rise to global fame, Arnaud responded to our inquiry by saying that Berrie could be the equal of Brézé, if not even more compelling. This nugget was on the back burner until we received an unexpected email from Gilles’ daughter, Céléste, a young Parisian who was at the time braving life in New York City. In her message and during a subsequent phone call, she told us about her family, who had taken over a property in Berrie and immediately converted to organic farming, and it was the word Berrie/Berrye that caught my attention.

Gilles Colinet

With a sparkle in his eyes, the theatrical Gilles is infatuated with the mystery of his new and much-beloved castle. Rarely have I met a more gleeful and excited man in his sixties with such an overwhelming project that appears to need another lifetime to finish. It’s scheduled for completion in five years (so it’ll probably happen in ten).

In the last two years, five new growers around Saumur have signed on with our national program in the US, and each holds promise in their unique way. Our first visit during this trip to Saumur was the historic Puy-Notre-Dame domaine, Forteresse de Berrye. After I saw the potential in the vineyards and Gilles’ serious approach to elevating his new property to a world-class level, I suggested he connect with Arnaud Lambert’s consulting enologist, Olivier Barbou. Olivier joined him immediately, and the following year Gilles signed Loïc Yven as their new Chef du Culture (vineyard manager), who was at the time with the Nady Foucault consulted project, Domaine des Closier.

The Vineyards

Gilles lucked out with this historic property, whose ancient military base and vineyards are perched above the expansive territory, with a great view of the surroundings. While the lower areas are a mix of unsorted alluvium and capable of rendering good wines, their complexity has limits. The key to all the exceptional wines in the region is that magic sandy tuffeau limestone rock preserved above these ancient flood plains and in contact with the vine roots.

Twenty miles south of Saumur city center and ten miles south of Brézé lies Berrie, where Gilles lives in his childhood dream castle—man, if he had it when he was a kid playing “fort”, he would’ve definitely been the king among his friends! As with all ancient military outposts, FdB was strategically placed atop one of the higher hills in Saumur—the key to its spectacular terroirs with vine roots digging deep into the limestone-capped hill after relatively thin topsoil. (For comparison, the vineyards are about 30-50 meters higher on average than those of Brézé and much of Saumur-Champigny.) The texture and quality hierarchy of topsoil and underlying soil here and in many adjacent parcels on the hillside have yet to be clearly defined. We’ll know more in the future. How exciting!

The entire property is 26 hectares, though 12.5 are under vine, with 2.5 of those recent replantings. The rest is forest and grain plantations below the vines, with six hectares now working with agroforestry principles, including almond, walnut, and other indigenous trees. The vines average around thirty years old, and most are clonal selections rather than massale, as in most of Saumur. Every region with a recent history of low-priced wines, like Saumur, opted for clonal selections when replanting because certain clones are much more productive. This history of quantity over quality is a challenge for the area. However, little by little, more quality-oriented genetic material will be planted in the region as Saumur growers aim for quality over quantity and will fetch prices to cover those costs. That said, the material of FdB demonstrates quality in the few examples thus far. There is depth to the wines, especially the Chenin Blanc.

The bedrock in the area dates to the Turonian of the Upper Cretaceous geological epoch, which developed between 94 and 90 million years ago. The bedrock exposed around the fortress is mostly yellowish tuffeau limestone—à la Clos des Carmes, the monopole cru of Romain Guiberteau that sits at the precipice of Brézé. Yellow tuffeau (note the yellowish tint on the rocks and walls of a cave there) is known to be of marine origin. The grayish-white tuffeau is usually lacustrine, similar to calcareous materials but from freshwater. Yellow tuffeau takes its color from a greater iron content, thus hypothetically endowing the wines with a little more oomph. The topsoil is a mixture of silt, sand and clay, depending on the parcel, all deposited during periods of flooding and mixed with what was unearthed from the underlying bedrock. Floods did a lot, even depositing a lot of orange and purple silex (chert) on much of the flooded areas (though they likely have little to no influence on the wines’ taste because they’re only a superficial topsoil element brought in from elsewhere). But human intervention has greatly influenced the topsoil composition through machine ripping. Regular plowing breaks up tuffeau bedrock, bringing it into the topsoil matrix, making it more easily erodible while clearing a path for roots to more easily find the highly-calcareous bedrock.

The Wines

Gilles hopes that his wines will be seen as authentic and with a pure voice of their terroir. He likes those that are “as light as clouds,” and wants them to be delicious and filled with pleasure. He mostly prefers wines with some age, especially reds where the tannins have “melted” away. This Bretagne native, with an inherent (as well as acquired) green thumb, maintains his boyish romantic perception of wine and wants what he makes to be fine and thoughtful, more melodic than thunderous. In this land of lightning and density, in the glass, I’m happy he’s taking that position.

There are three main wines in Gilles’ initial range. In the future, after much exploration with Olivier, there will likely be a series of different parcel selections because of the variability of each plot. There are many around the castle, and not contiguous in ownership.

The Chenin Blancs, “Les Bourgères” and “Promesses,” with the latter’s label designed by a local Saumur artist, both carry a little bit of that Montlouis/Vouvray sweet and exotic grapey green and waterlogged, clean forest-floor dampness, two qualities in Chenin that, when done well, are utterly alluring. The Cabernet Franc, when on its own, is like smelling and tasting black earth, wet green forest, wet gravel, and wild berries—classic in every way.

The Crémant de Loire already feels like a “parcelaire” selection as a sparkling wine entirely from their Chenin Blanc plots rather than a mix of different communes, as many others in the region are. This monovarietal crémant ferments in concrete for almost two weeks and is then aged further in concrete before bottling. The dosage depends on the year, with 4g/L in the 2020. In the future, some base wine will be held back to supplement subsequent vintages for added depth and texture.

Their new 2023s have just arrived, the second season under the gentle guidance of Olivier. After more than fifteen years of exploration with Arnaud and more with dozens of other growers, Olivier’s experience and touch are evident. He also understands Gilles’ predilection for wine, which aligns with mine: pure, raw and focused, without artifice and over-stylizing. With inferior terroirs, this approach is perhaps less interesting, but like the highest-quality fish in the hands of a sushi master, wines from fabulous terroirs need to be let alone and served unadorned to highlight their quality. Gilles cleverly explores his vineyard’s potential through this more naked state to better understand which plots are the most promising and how to bring out their best.

The racy, chalky, citrusy 2023 Crémant, made entirely from Chenin Blanc, with a dosage of 5g/L, is the first in line for the newly arrived wines; the first batch of bubbles from the domaine blistered out of stock and into the market in a heartbeat. The 2023 is a fabulous follow up. Since our first visit to this domaine, whether under the previous owner or under Gilles, it is sure that this property has a talent for bubbles.

The 2023 Saumur Blanc “Les Bourgeres” is a classic Chenin Blanc that echoes many celebrated white wine regions of northern Europe. It comes from vines planted in 1993 on tuffeau limestone bedrock with relatively thin topsoil of calcareous silt, sand and clay. It’s raised in concrete and old barrels of 225-400 liters, and is deeply green, like exotic moss, chlorophyll, reposado tequila, lime and salt with a light honeyed finish. I’ve said since my first tastes of earlier wines, even before Gilles took over, they reminded me much more of Vouvray than Saumur, or Riesling with the softness of Sonnenuhr, or Domprobst, with the limestone force of a Keller Von Der Fels. Despite the warm season, the 2023 finds great lift without jarring tension. It’s elegant, refined and yet another preview of the potential of this property with Chenin Blanc.

The 2023 Saumur Blanc “Promesses” will arrive later this spring.

Their 2023 Saumur Rouge “Clos de Berrie” comes from vines planted in 2012. It’s vigorous, high-energy Cabernet Franc with a sturdy and wiry frame, perhaps due to its tuffeau bedrock under a shallow loamy topsoil rich in calcareous sands. This year is a lighter than the 2022 and shows nice gentle curves with a looser frame. Tannins are fine but sharp, with balanced green characteristics to complement the cool and refreshing limestone tension.