Newsletter April 2025

Diego Collarte, Cume do Avia, Ribeiro

Is there anything but strange happenings lately? The last decade produced some memorable moments for all of us as the wine import business, restaurants and retailers have constantly teetered between epic meltdowns and nearly irreparable disasters. Nothing has been easy and current events keep throwing more wrenches into the works.

So then, what do you get when you cross a warm winter, a warm spring, and a hot summer with numerous heat waves recording the hottest year in Europe on record? Indeed, not only the sweaty Catalan gasp of Insuportable!, but also great white wines. Yeah, that happened–some good news.

I posed the question everywhere on my warp-speed winter wine tour with Remy, our New York captain, across six countries where makers were selling their 2022s. As I suspected, most of them credited the 2021 season for providing the vines with greater resistance to 2022’s solar beatdown. And after a series of hot summers, Mother Nature struck back in 2021, shut out the sun, and replenished the well. It was also a month-long never-ending feast for mildew, to the point where growers actually began to miss the relentless summer sun. But the pump was primed, and 2022 delivered—not only on quantity but also with quality.

I love exfoliating, tenderizing, vibrating and borderline abusive acidity and I expected many 2022 European white wines to be a little flat, which is typical in hot years. Instead, there’s thrust and energy alongside a sun-kissed fruit profile and many aren’t just good, they’re excellent. For a lot of growers, the crop was bigger, which helped reduce the high concentration most common in balmy vintages and also made up for the losses of 2021.

As I write this segment, I’m sipping on Vincent Bergeron’s 2022 ‘Matin, Midi, et Soir’ Chenin Blanc from Montlouis-sur-Loire, which will hopefully arrive at the end of April without a 200% tax. Each new pour picks up momentum and tension, increments of cooler and cooler freshness. While tasting his 2022s out of barrel, I couldn’t read them well—maybe I was too in my head about what I expected from the hot season. But across our Northern European white wine territory, from Austria to Galicia, makers were met with success—with few exceptions. Because of their deeply embedded location inside Europe’s continental climate influence, our Austrian and German growers were the true test. Of all grapes, dry Riesling is most prone to fall flat when the vines are overheated. They remain complex, at least by definition, but their libido goes … well, a little limp.

The 2022 Rieslings of Wechsler, Malat, Tegernseerhof, Veyder-Malberg, and Muthenthaler? Energy-filled, with surprising torque. So are the Austrians’ Grüner Veltliners. Our two Chablis growers, Christophe and Collet pulled it off. Few anywhere are salty shredders like the Val do Salnés 2022 Albariños, which many growers there consider their best vintage in years. So far, I’m enjoying these longboarding 2022s, soul surfing in the diffused rays of a low winter sun.

There are some great reds, too. In continental areas, the balance is still intact, but the fruit is juicier and the wines stouter. But growers who’ve recently moved from power toward a gentler approach played well in 2022. It’s a vintage with the potential to create bruisers, but so far with our growers, it’s loads of purity and the unmistakable echo of their terroirs.

Dave Fletcher, our Barbaresco grower (available in select markets), described the 2022 fruit as the most immaculate of his career. It’s not that they’re necessarily perfect in profile (perhaps missing some floral and brighter red tones), but the clusters in hand were without imperfection. And, like the top-quality 2022 Val do Salnés Albariños, the reds of Galicia hit their highest notes. They are ideal examples to represent this region’s potential for reds. The fruit and charm are more on display than the typically pronounced angles, squares, and jolts of metal and mineral from their rock-and-roll terroirs.

Unofficial port authority, Salerno 2018

I hope you’re not like me—weaned on Côte d’Or, which carved my preferences in stone and sometimes led to my donning a pair of blinders. Enmeshed nostalgia for our past influences is a strong default, especially when challenged by the enormity of the constant and rapidly accelerating variations in the wine world’s evolution. It captured my primitive wine mind early, narrowed my focus, and became the benchmark to which I compare every other wine on the planet. It hit the bullseye, and everything else landed in the outer rings. And I remain as guilty at times of regressing as anyone, though I tell myself that at least Côte d’Or wasn’t a bad place to backslide into.

“Burgundy has the advantage of a clear, direct appeal, immediately pleasing and easy to comprehend on a primary level.”

-A.J. Liebling, Between Meals: An Appetite for Paris, 1959.

My Côte d’Or-influenced bias leaned more toward red than white. New oak notes in the forefront have never been my inclination, but the older more structured Côte d’Or reds seemed to digest it well. Now, gargantuanly fruity reds in hot years still have the same levels of new oak and taste like either a slightly sloppy smash-burgundy or a material display of wealth rather than of cultural and intellectual value—a surface allure of riches, to be paraded to a table of those who often lack appreciation for a wine’s relevance–the art of the thing.

Malat cellar, Kremstal

Few whites in the world, if any, wear woody bling better than Chardonnay from the Côte d’Or, but my preference for neutral aging vessels (mostly older wood barrels or concrete rather than steel) was yet another product of my wine youth. In the late 90s Austrian wines (for me, more Riesling than Grüner Veltliner) became the next thing and influenced me greatly. More neutral aging vessels on whites illuminates their directness and highlights their terroir. Between the two early influencers of red and white, that of the more neutral vessel with white wines remains closest.

Below in the section, “France Part Two: North Central,” you will find more information about two of our most important new arrivals this month from two organically certified farmers and growers. First are Jean Collet’s 2022 Chablis Premier Crus and Grand Crus. In my experience, Collet is one of the most reliable domaines in Chablis for warmer seasons. The wines migrate from cooler years that are unmistakably classic, and in the warmer years, they’re like a marriage of Chablis’ nuances with Côte d’Or’ and Mâconnais’ sunnier fruit qualities. While in warm years Chardonnay can be a bore, Collet’s ‘22s still express their origins and will be quite crowd-pleasing for a typical restaurant guest, more than those who love a Chablis with a sharper edge.

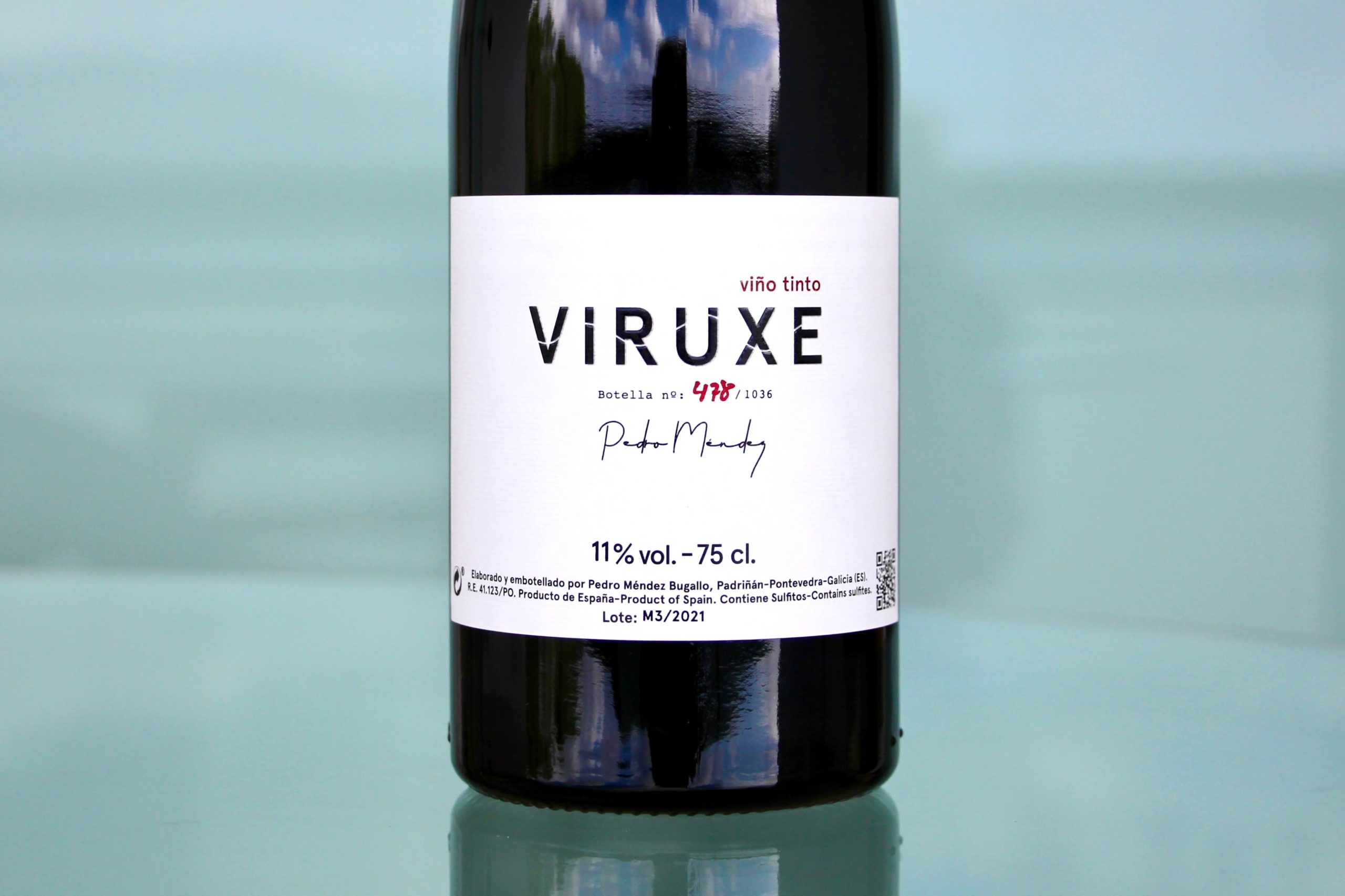

The most successful regions of 2022 inside our collection of whites are those of Galicia, specifically Rías Baixas and Ribeiro. The 2022 Val do Salnés Albariños of Manuel Moldes and Pedro Méndez are undoubtedly the best we’ve experienced from them. Manuel (Chicho) describes it as his best year ever, and those who enjoyed his 2022 Albariño ‘Afelio’ and Pedro’s 2022 starter Albariño already know what’s coming with the imminent arrival of their parcela selections.

Manuel Moldes and an ancient Albariño vine in “Peai”

The 2022 Albariños arriving from Manuel Moldes are A Capela de Aios, a wine made from 70-80-year-old vines on severely decomposed ancient, Pangean-era schist with a rich topsoil, Peai, another Albariño on schist but harder bedrock than A Capela de Aios and similar topsoil, and As Dunas from schist-derived beach sand. Each is raised in old 500-600 L French oak and they’re quite different. As Dunas finds a unique set of aromatic characteristics unlike any other Albariños in the region (except those of Rodrigo Méndez and Raul Pérez, who bottle two different wines, one under Forjas del Salnés and Rodrigo Mendez’s eponymous label) and remarkably powerful for a wine from beach-like sand. Peai, pronounced P.I., like Magnum P.I., might be the most structured of the bunch, a powerhouse puncher with a dense nucleus and an intensely salty mineral orbit.

A Capela de Aios is the foundational wine of the bodega—the first of his Albariños from schist, and one of the first in the region to acknowledge its geological difference—a true anomaly in this granite-dominated region. In the years past, it was heavier and richer; a gilded but deeply complex and slightly baroque wine. But in 2021, there was a change, a finer line drawn in its sandy-loam schist soil. The 2021 lit the way, but the 2022 walked the path up to this vineyard’s zenith, like a star at the peak of its nuclear fusion—harmony is now in perfect equilibrium. While As Dunas and Peai have opposing qualities, Chicho’s ‘22 A Capela de Aios combines their best qualities and finds its newest level. It may be the most compelling young wine I’ve had from him, which also makes it perhaps the most compelling and complete young Albariño I’ve ever had.

Also arriving from Moldes is his 2023 Albariño ‘Afelio.’ 2023 was another successful year with a slower growing season. Each year after the new wines are buttoned up for aging, my wife and I meet up with Chicho and his wife, Silvia, and he says the same thing no matter the season: “A really difficult vintage but I am very happy with the results.” Afelio is Chicho’s wine grown almost entirely on granite soils. It’s highly mineral but more fluid compared to his three parcela wines on schist that often pack a tighter punch. Most of this wine comes from further north of the schist outcrop just north of Sanxenxo. In 2018, he and I discussed raising more wine in older barrels, and he’s now incorporating new large foudres.

2022 was a great year for Galician reds, too. There’s nothing more that Rías Baixas needs than a consistent season with some sun, warm daytime temperatures and the ocean-cold nights to ripen their reds to beyond a bearable pitch. A 50-50 blend of Caíño Tinto and Espadeiro from old vines (some pre-phylloxera), the 2022 Acios Mouro’s summer and fall red fruit profile is as bright as usual but softer and more generously juicy to balance its light balsamic notes and high acidity—a natural characteristic not only spurred by the cooler climate but the extremely high acid of these two varieties. Acios Mouros has become a cult favorite for those who know it, but it might be better served by leaving it for professionals and adventurers who like an intense experience. If you’re looking for a simply relaxing moment with a glass of red, this probably won’t be your copa de vino.

Chicho’s wines move out of our warehouse like we’re having a fire sale, so if you are interested, please let us know soon.

Pedro Méndez and an ancient Albariño vine for ‘Tresvellas’

Dancing around the 2022s are two new arrivals from Pedro Méndez. Both are unofficial non-D.O. wines made entirely from Albariño in the Rías Baixas Val do Salnés area of Meaño, the historical viticultural center of Val do Salnés.

The 2023 Pedro Méndez ‘Viño Branco do Val’ eponymous label is a fabulous follow-up to the double-take inducing ‘22 that took everyone by force and charm. 2023 is tighter in some respects and narrows more quickly to a more minerally point. (But don’t forget that if you’ve recently had the 2022, this 2023 with a year less in bottle will be more piercing until it settles in a bit further.) It’s harvested from a broad collection of small parcels in Meaño, from young to ancient vines, giving it a wide range of complexities. It sneaks in just under the limit for by-the-glass programs but will deliver on expectations for that upper-tier price.

Liquid gold and platinum Albariño is bottled up in the 2021 Tresvellas ‘Viño Branco de Viñedos Historicos.’ Continuing its winning streak after the ‘19 and ‘20 versions from these ancient vines that look more like trees, each of these 100-year-old-plus vines (with a few estimated to be around 200 years old) were able to maintain their root systems free of the aphid due to their silty and finely sandy soil grain. Many for this wine are next to a small creek at the bottom of the hill on super fine silt, and are used as budwood for all new plantings in that area—they are not only the Tresvellas (Three Old Ladies), they’re the mothers of almost every young Albariño vine around them. Another borrow from a previous newsletter, as this wine doesn’t miss a beat from the earlier versions: “With concentration, depth, and restraint, the warm and well-worked Tresvellas fills the glass. All the varietal’s classic high-toned lemony notes went to full preserves: sweet, salty, acidic, zest oil and the right amount of bitter pith. The color is between straw and gold leaf and it tastes expensive.” This is one of Rías Baixas’ most triumphant bottlings, and one not to be missed. Though stout to the core, it’s also generous and filled with the joy of its ancient mothers surrounded by their thriving babies.

Iago Garrido, Augalevada

From serious to the most serious of our Galician growers, former professional Spanish futboller turned virtual modern-day Cistercian cellar monk, Augalevada’s Iago Garrido recentered his athletic discipline from the highest level of sport to natural viticulture and precision cellar work.

Established by Benedictine monks in 889 A.D., the Monasterio de San Claudio de Ribeiro is perhaps Galicia’s most historic viticultural center from the Middle Ages. Iago’s proprietary vines are a few kilometers to the east on a sliver of granitic land carved out into an amphitheater facing the sun where vines were first probably planted more than a thousand years ago. Today, those vines “replanted” again between 2008 and 2010, and grafted over a few times to varieties that he gravitated toward as his ideas for the kind of wines he wanted to make, crystallized. Fully committed to biodynamic farming since the first plantation, he wed himself to Treixadura, a variety that produces soft and agreeable white-fruited and herbaceous wines, but eventually left her for a much racier pair, Lado and Agudelo—the latter also known as Chenin Blanc (first identified by a Spanish ampelographer exactly a hundred years ago this year, though it’s believed to have been brought in centuries earlier). This duo comprises the new 50-50 blend of his 2022 ‘Ollos de Roque,’ (Eyes of Roque, Iago’s son). But first, we have to introduce you to the 2021 ‘Ollos de Roque,’ a blend of the gently structured Treixadura balanced with the extremely high acid, minerally-dense varieties, Lado and Agudelo. This flor-influenced, old oak and amphora wine is Iago’s flagship.

His other white from Ribeiro, 2022 ‘Ollos Branco,’ is a blend of 15-50-year-old Treixadura, Albariño and Godello from organically farmed vineyard of Manolo de Traveso and other parcels in the three unofficial Ribeiro subzones Arnoia, Avia, and Miño. This is the right introduction to Iago’s Neil Gaiman-like wine universe where everything is fascinating and far from typical. All his wines up to this release are under the influence of flor, which was naturally discovered on his property when he buried an amphora with wine out in his granite terraces. It’s a striking wine filled with moments of almost unbearable tension, liberation and euphoria. One needs a meditative journey to uncover all its secrets that evolve from one sip to the next. It’s a brilliant wine, though perhaps too Lynch and Kandinsky for the common drinker.

Out of Ribeiro and into Monterrei, one of Galicia’s D.O.s furthest to the southeast and perhaps its warmest, is Iago’s 2022 ‘Areas de Rei.’ A play on words, it means “king’s areas,” but also “areas” in Gallego means sand (in this case, sand from granite), and Rei, as in Monter-Rei. It’s sourced from 80-year-old vines on granite at altitudes exceeding 450m. A strange name for a grape, Dona Branca can almost always produce innocuous, perfumy white wine with low acidity. But put her in the hands of a wild man with a brain that works overtime outside the box, and something altogether different arrives. It’s hard to describe such wines, but let’s say it’s mildly floral, spare in fruit but white fruited, salty for days, earthy, spicy and utterly savory. It’s a wine that mystifies me—not for the first time with Iago’s wines—and there is certainly a place for it on the right menus.

The most electrically charged in his high-voltage range is yet another Albariño in our collection of five growers who make the stuff. 2022 Val do Salnés Albariño “Parcela Eiravedra” comes from 60-year-old Albariño vines just three kilometers from the ocean in the Val do Salnés. This is Luke’s Return of the Jedi green lightsaber in liquid form, a bottle of aurora borealis; it’s mean to some and absolute glory to others–and I’m one of those others. Older vintages are denser and almost offensive to some who don’t appreciate the high voltage. In recent years, he found a way to calm the current and make it play nice. It’s a beauty, and one of the great representations of salty, minerally and high-strung Albariños, though it’s made in a cellar far far away from its roots.

I love Iago’s whites, but I am a bigger sucker for his reds. He’s never as proud of them as he is for his whites, and I don’t understand this. I’m not sure what he’s searching for, but I keep finding what I want. They’re so fresh and vibrant, clean yet character-filled, more analog than the usual digital waveform Galician reds, with thin frames but a solid smack of affection. The 2022 ‘Ollos’ Tinto and 2022 ‘Ollos de Maia’ (named after his daughter, Maia) have found a new level. The differences aren’t so great, but Ollos Tinto is a blend of young and old vines of Caiño Longo, Brancellao, Espadeiro and Sousón from organic and sustainably farmed vineyards on granite and gneiss, and Ollos de Maia is a blend of 15-year-old, biodynamically farmed vines of 45% Caiño Longo, 45% Brancellao, and 10% Caíño da Terra, from the unofficial Miño subzone on granite.

The whole-cluster management may have been the biggest factor, at least outside of learning how to do things better each year—this guy’s a fast learner. It went from fully destemmed in 2018 (which I also adored, as I drank at least three cases, maybe four over a few months—no exaggeration), to 2019 partial whole cluster, then to 100% whole cluster in 2020, and now to about one-third in 2022. During those 100% whole-cluster years, the wines needed more time once open to find their footing. We spoke about this subject at length in 2021 on our first visit after the borders reopened as we tasted the 2020s. I explained that I was worried about clipping the fruit with too much whole bunch; in this part of the world, fruit is a needed asset that doesn’t always come easily with these indigenous red varieties (not including Mencía) that tend to overload on metal, mineral, earth and flower. They are naturally intense channelers of the region’s hardcore acid bedrock and topsoil that often seem to overdose their wines with minerally and metallic angles. But this year he nailed it. Everything is in place: fruit, freshness, authenticity, and the coming together of the seventeen years of the Camino de Iago. For someone who rarely seems satisfied with his work, even when it’s extraordinary, the question is, where will he go next?

We arrive at the last of this month’s 2022 white wine act. And what a way to finish the story of the white wines with the arrival of Katharina Wechsler’s 2022 Westhofen Riesling Grand Crus, Kirchspiel, and Morstein, as well as Katharina’s monopole cru in between, Benn, among others.

I hoped Europe’s hottest year on record would be as gentle to the vines here in the Rheinhessen as it was elsewhere. Same story: 2021 filled the well and helped the vines maintain their resilience through a scorcher, yielding a collection of superb dry Rieslings with unexpectedly strong punching power. Even Katharina’s 2022 Riesling Trocken, the starter in her range, is an especially powerful wine. Of course, many of the areas with limestone, a rock with good water retention, and clay, were well advantaged over those regions with sandier soils that had a harder time fending off the heat and protecting the grapes.

Benn, the family’s tiny monopole vineyard site, has perhaps the most diverse plantations of all her vineyard parcels. The warmest of Katharina’s three important crus, it’s composed mostly of loess topsoil in the lower sections that sit as low as 120m, and limestone in the upper part, peaking around 160m. Quality Riesling thrives with suffering vines, which is why much of the non-Riesling vines are planted in the lower sections. Its 50-year-old Riesling vines, particularly those used for Wechsler’s top-flight trocken bottling, are planted in limestone bedrock and limestone and loess topsoil toward the top, not too far away from the bottom of Morstein. Benn produces a substantial Riesling that expresses impressive moments, especially with more time in the glass. When the others shine so brightly in their specific ways, Benn has been upfront but is somehow still a slower burn.

Katharina Wechsler, photo credit to her husband, Manu

Kirchspiel is a great vineyard and screams its grand cru status as soon as it’s opened, especially the 2022. It’s always readier out of the gates—often in the range of other growers—and for many reasons. Shaped like an amphitheater facing the Rhine River (though still roughly five miles away) with its southeastern exposure an average of around a thirty percent gradient, its bedrock and topsoil is composed of clay marls, limestone and loess. It’s a warmer site than Morstein because of its lower altitude (between 140m-180m) along with the curvature of the hillside that allows it to maintain greater warmth inside this small but sheltering topographical feature from cold westerly winds. Katharina has three different parcels in this large vineyard with reasonably good separation, giving the resulting wines a broader range of complexity and greater balance.

Morstein, Rheinhessen’s juggernaut limestone-based dry Riesling vineyard is—even with vines only replanted in 2012—the undisputed big boy in Katharina’s dry Riesling range. Katharina’s Morstein vines are massale selections from the Mosel and have smaller, looser clusters with naturally low yields, even from the young vines. A mere pup by the standard of vine age, Katharina’s Morstein is formidable. And while it’s not usually as flashy out of the gates as Kirchspiel, it picks up serious power and expansive complexities that know no end. Like many of the world’s great wines, Morstein is no rapid takeoff F-15 fighter jet with instant supersonic speeds, it’s a rocket ship with a slow initial takeoff and a steady climb that reaches 17,000 mph before entering orbit. The topsoil is known as terra fusca (black earth), a soil matrix of heavy brown clay. Its low to medium topsoil depth (by vinous standards), combined with limestone fragments from the underlying bedrock makes its ability for water storage more limited than Katharina’s other main sites.

Other 2022 wines arriving from Katharina start with her mid-tier dry Riesling, Kalk (formerly labeled Westhofen Trocken), a wine entirely composed of the younger vines of Kirchspiel, making it a fabulous deal! And the greatest deal in the bunch, the Riesling Trocken is about to arrive, which also benefits from a large percentage of Kirchspiel fruit. And finally, in the range of dry white wines, her Scheurebe Trocken, made in a classic way, and the Scheurebe Fehlfarbe, an orange wine. Lastly, but often first in my summer wine line, the Kirchspiel Kabinett, one I begged her to make and with which I’m now completely obsessed. It’s a wealth of riches from Wechsler at unbelievably fair prices for such talented terroirs.

Remy Giannico and Jean Delunay, an old master of Bourgueil, Domaine de la Lande

Only thirty kilometers east of Saumur, Bourgueil feels so much farther away. Maybe going into flat lands after Saumur’s limestone perches over the river with troglodyte dwellings and limestone mansions, ornate pasty white tuffeau châteaux surrounded by residences built with the same white stone, and the absurdly beautiful, overindulgent churches (like the hemispherical-domed Notre Dame des Ardilliers, scrunched between the bluffs and river) with their glistening gray slate roofs hued green-gold with the same lichen found on the region’s vines. The majesty of Saumur’s inspired buildings seems to descend into Bourgueil’s more serviceable and industrial buildings on the north side of the Loire.

But once inside its vineyards, Bourgueil’s are just as exciting as Saumur. That is to say, they don’t look like they would render wines that would send a shiver of excitement down your spine or make your hair stand on end. But if the wines couldn’t, those 12th-century Cistercian monks would’ve split faster than it took them to plant and wait a few years to taste their first few harvests. But like many of the world’s unassuming vineyard sites that generate life-changing wines, you gotta go to where the root meets the rock. Those clever monks knew the magic of Bourgueil started mid-slope and continued farther up into the clay-rich rocky topsoil and limestone bedrock not too far underneath.

Bourgueil has long been overshadowed by its neighbor, Chinon (at least in the US market). Maybe because it’s easier to pronounce? The word is more guttural than Chinon, which somehow sounds more noble, even if its name originates from the word, Canetum, which means swampy area. Maybe Bourgueil would be more accessible if they left it to its Latin origin, Burgus, or even when that evolved to Burgolium before Bourgueil. They got the Bourg part right, that’s easy. But the last syllable with all those vowels is tough for the back of the throat of English speakers. Maybe it’s Chinon’s dark yet romantic connection to Jeanne d’Arc? The Saumur-esque reemergence of magnificent ancient buildings overlooking a river, like the Château de Chinon, with even more charming residences than in Saumur? Maybe it’s the wine? Perhaps Bourgueil is viewed as more rustic than the typical Chinon, but this doesn’t seem plausible to me …

On a mostly contiguous slope on the north side of the Loire River, the landscape of Bourgueil and Saint-Nicolas-de-Bourgueil (SNdB) is shaped much like parts of the Côte d’Or, or high quality Champagne spots. Chinon is more topographically diverse and mostly former marshland sandwiched between the Loire and Vienne like Montlouis-sur-Loire’s vineyards are between the Loire and Cher. Perhaps it’s a matter of more gravelly and sandy sites in Chinon? I don’t know, but Bourgueil’s wines have great potential and deliver on the authenticity of terroir as strongly as anywhere in France. And perhaps more growers here are committed to a more classical style, which seems to be coming around again.

After an evening tasting and dinner that included his spectacular new release of Arnaud Lambert’s 2023 Saumur “Midi” (formerly known as Clos du Midi) arriving in California this April, Remy and I left Arnaud’s, we headed east toward Touraine and into Bourgueil to Domaine de la Lande. There we met with François Delaunay and his kids, Pauline and Thomas, and his father, Jean, a charming well-aged vigneron responsible for crafting some of the greatest old Cabernet Franc I’ve ever had the pleasure to drink.

François Delunay, a young master of Bourgueil

Because we were so tight on time, and I didn’t expect that Remy could sell the wines in New York, we had a quick tasting of their precisely crafted and wonderfully expressive new releases. We then went straight to their organically farmed vineyards (certified since 2013 under François’ direction) and, despite running late, were enticed into their limestone lair for my third round of extraordinary old bottles that dated back to the 60s.

In a past newsletter, I wrote about my experience with their old wines and how I managed to procure four cases back to the earliest part of the 1980s, when Jean made all the wines. There wasn’t even close to a single dud in the entire bunch and it was by far the greatest batch of old wines I’ve ever purchased from any domaine, the prices ranging between that of a good sandwich and a three-course lunch menu at a decent bistro while they all delivered a long-drawn-out Michelin experience of constantly evolving vinous courses.

2 pm is already too late for lunch in France. But we had skipped breakfast, and I couldn’t drag Remy to the next appointment hangry. We had no choice but to grab a grocery store sandwich, even though I knew being late for lunch in France was a bad idea. Those stale and tuffeu-white sandwiches with a paper-thin, salty, reddish cross-section of animal lacked nourishment. They only served to bloat and balance us out a little after our undeserved and illuminating rarities cellar tasting with the Delaunay family.

The Delaunay’s unexpectedly offered us the opportunity to represent their work in the entirety of the United States, and I knew everyone needed to be introduced to these wines. Their wines are as honest and pure as any found in all “wines of place” inside France. And most of the time, in the middle of your wine discoveries, don’t you want at the very least an honest wine? Brutally honest, or even just brutal? So long as it’s true? It’s easy to feel cheated with wines that lost their identity through too much tinkering. Like they’ve cheated you, cheated themselves, cheated their terroir. You won’t find that in anything coming from the Delaunay family.

Was ‘sur-Loire’ really necessary? Montlouis alone sounds noteworthy; regal, even Royal: Mountain of Louis! Now that carries weight! But Mount Louis on the Loire? No. Would Volnay-sur-Saône sound like a glorious terroir? A name says it’s only as good as a secondary appellation … Paulliac-sur-Gironde? Unclassified swill … Cornas-sur-Rhône? Cheap! Montlouis’ hyphens and dead-weight words hold it back! Vouvray? Two syllables. Clean—like a sword unsheathing from a metal scabbard. Or, a challenge to a duel, “Tu as insulté mon honneur! Je demande un Vouvray !!” Well, it turns out that this was actually said in a celebrated French restaurant by a nobleman after they had sold out of Vouvray, and Montlouis-sur-Loire was offered in its place …

With or without Sur-Loire, Montlouis is indeed old but these days it’s a newish frontier with a second generational wave of boutique growers rising in the ranks of quality for Chenin Blanc. The natural wine movement sparked it, and what better appellation to spawn a group of rebels to challenge the establishment across the river in Vouvray. It may be Touraine’s mirror of Saumur as an overlooked appellation creating unexpected waves. Interestingly, I recently received a message from Arnaud Lambert asking for me to write a letter—which I did—in support of the Saumur growers application for a new Dénominations Géographiques Communales (DGCs) that includes the six names: La Côte (some areas inside of Saumur-Champigny), Brézé, Berrie, Brossay, Puy-Notre-Dame, and Courchamps. However, Saumur has nearly ten times the surface area of vineyards than Montlouis’ 400 hectares. This warrants some delineation.

The first of our three Source underground Montlouis luminaries (one of whom is still withholding our US allocation because Trump got elected) is Vincent Bergeron, a man whose humility and generosity continues to inspire me to better myself. He’s a gem of a human being. It was easy for Remy, our Los Angeles tastemaker JD, and me (the first time I met him in 2022), to want to do everything possible to support such a person and bring him the recognition he deserves. Borrowing from the website profile I wrote a few years ago, “Vincent is rare in today’s world of self-aggrandizing young vigneron talents—sometimes appointed by the wine community and often by the self, as “rock stars.” Many seek celebrity and membership in idealist tribes rather than going for truth and an honest view into this métier, this artistic pursuit, this craft–a marriage between homo-sapiens and nature. Vincent is a vigneron’s vigneron, a human’s human, an uncontrived example of how to live and simply let be, spiritually, without trying to be someone.”

Soul-filled? Angelic? These are two impressions that come to mind with Vincent’s wines. He crafts some quite serious but inviting organic, and, most of the time, no-added-sulfites Montlouis wines. Again, as I put it years ago: “Emotionally piercing, Vincent’s mineral-spring, salty-tear, petrichor Chenin wines flutter and revitalize; a baptism of stardust in his bubbles and stills—a little Bowie, a lot of Bach. His Pinot Noir is earthen en bouche, and aromatically atmospheric, bursting with a fire of bright, forest-foraged berries and wildflowers, and cool, savory herbs rarely found in today’s often overworked, oak-soaked, and now sun-punished Pinot Noirs, the wines that were the heroes of the past millennium, but today are a flower wilting under the relentless sun. Advances in the spiritual heartland of Pinot Noir have been made, though I sure miss the flavors of the Côte d’Or from my earlier years among wine.” Vincent’s Pinot Noir takes me back to the beginning of my love affair with this grape’s propensity to produce the world’s most beguiling and slightly austere red wines.

Vincent’s range of 2022 Chenin Blanc is arriving in May (we hope without 200% tariffs!) with the vineyard blended, ‘Matin, Midi et Soir’ and the lieu-dit, “Maison Marchandelle,” two of the most convincing 2022s I’ve had, and his Pet-nat, “Certains l’Aiment Sec” is about to land as well. Vincent’s 2022 still whites are some of the initial ones that helped me begin to recognize the quality of white wine from this vintage across Northern Europe. As mentioned in the introduction to this month’s newsletter, they’ve got legs and unexpected thrust for a year with such hot weather. And once I tasted 2022s from other makers, as mentioned early in this text, I was sure that the vintage has merit, a wine worthy of those who want and need a white wine with snap.

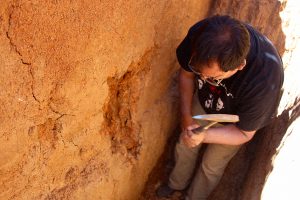

Vincent Bergeron in Maison Marchandelle, December 2024

Vincent’s Maison Marchandelle plots outlined in black—the green sections!

While standing in Maison Marchandelle, a 0.87-ha plot planted in 1970, Vincent lamented that this was the only vineyard he harvested grapes from this year. Outside of this small parcel, the rest of his 2.6 hectares of crop were destroyed by the constant mildew pressure of the season. He’s made it clear that if 2025 isn’t fruitful, he might have to hang up his vineyard boots, a personal tragedy. And if you know the wines and even more the man, it becomes a tragedy for us all. Fingers crossed. In the meantime, enjoy the masterful wines that we have on hand!

In 2024, Vincent managed to buy some fruit from one of last year’s new Source growers, Thomas Frissant. The morning after we visited Vincent we would stick our nose into the cellar of this young, well-trained, and technical cellar swashbuckler. His organic vineyards are located near Amboise, the final resting place of Leonardo da Vinci. We braved a walk through his vines (and he braved a drive with his truck through some pretty wet, slippery clay roads) for probably the coldest vineyard exploration of our trip. We thought it would be quick, but Thomas took us on the long route! I mean, how much silex does one need to see when it’s all over the place? It was bitingly wet and windy but glimmers of sun shone through that would’ve surely inspired Leo to paint, had he lived to 572 years old. Against my better judgment, I flew the drone. I could’ve easily lost it as I did its twin in Wachau’s Spitzer Graben seven months earlier. But this flat terrain presented no obstacles other than the fierce wind, so it returned and touched down with no problem.

Thomas’ wines are fabulous and mostly come from older vines and all are under organic certification. He has higher-end wines too, but the starter range is restaurant-program gold for the price, quality and vineyard culture. Their silex soils seem to endow them with that similar Pouilly-Fumé and east Sancerre hard-punching mineral quality. Sometimes it’s hard to break the market of such addictions when they deliver at these prices, but it’s perfectly fine with Thomas that we’re addicted and even particular regarding the selection we import from him. We blistered through the first batch we received in October, and the second one just landed a month ago and is on the move again with the two main features, 2023 Sauvignon Blanc, “Le Chapeau Comte” and 2023 Chardonnay, ‘Tout En Canon.’

Thomas Frissant

Nicolas Renard’s cellar

We won’t spend too much time on Nicolas Renard given the minuscule quantity of wines we’re allocated every other year, but we would finish our day tasting with him in his pharaoh-like tomb of a cellar. While we receive so little from Nico (pictured above), his wines are of the most substantive whites in our entire portfolio from seven countries. Nico is a magician with Chenin, Sauvignon, and Chardonnay. They’re epically singular (like the guy) and flirt with x-factor perfection. I can’t get enough of them, and once they’re open they’re unbreakable, and they have not a molecule of added sulfites. I asked Nico during my first visit in 2022 if some of the wines had had any sulfite additions at some point. It was the only time I ever felt like I had crossed a line with him. After his brow unfurled, his usually ever-present sheepish smile returned. His wines ferment for years (the last two whites we received, the 2017 Sauvignon and 2018 Chardonnay, finished fermenting in 2023) and I’ve not tasted many more intriguing wines out of barrel in the Loire Valley, though I could say the same for all the cellars I’ve visited in France. If there’s any Loire Valley grower whose wines should fetch massive second-market prices, it’s Nico’s. But good luck finding them, though I have faith they’ll come around again. The three restaurants in France that get a few bottles don’t even put them on the list, saving them for a rainy day, I guess. The rest that we don’t get are in Japan.

Le Berlot has become the communal restaurant of the growers most preoccupied with nature, in the area. It’s a tradition for me to meet up with everyone I know when I’m in town (again, now minus the guy who withdrew our allocation because of Trump), and I was most happy that our young Thomas joined us for dinner there with Nico and Vincent. Thomas already has the skills but a little of the magic dust that falls off Nico and Vincent wouldn’t be lost on him. Le Berlot has a good kitchen with only slight tweaks to more French classics, and a good selection of natural wines. There are so many names on it I don’t know that I need a virtual wine shaman to guide me through it. And if you’ve had too much to drink to get behind the wheel (so less than two glasses with France’s tolerance of 5g/L of blood alcohol level), they have dorm-style private rooms upstairs, but with shared bathrooms. The legend of after-hours here is quickly gaining a reputation, though I’ve been lucky enough to avoid any unwelcome long nights and space shared with strangers.

Domaine Jean Collet and Christophe et Fils amplified my perception of northern Europe’s unexpectedly successful 2022 white wines. (Perhaps southern Europe was also successful, but that’s not where we have a strong position with white wine.) And I mean unexpected only because I thought they would be shorter on energy. But they’re not. They have plenty but are even maybe less corpulent and rich than I expected. They go down easy, but they don’t have the premature notes I associate with struggling vines and sun-tested clusters in other warm seasons in Chablis.

We tasted Christophe’s 2022s for context with his recently bottled 2023s. The 2023s were sparer in body at the time because of their recent sulfite addition at bottling just some weeks before. 2023 was yet another sunny year, and we’ll see how it will compare to the 22s. In any case, the 22s showed very well. Maybe this vintage won’t live forever in the context of age-worthy Chablis seasons, but who cares? I suppose that in the three years after their release, 95% of every bottle of 2022 will already be down the hatch, and that seems like a good time for them.

Curious to see what others thought of the year, I checked out a critic’s website and how they tasted and scored the Chablis growers of 2022. A lot was tasted blind at BIVB, the Bureau Interprofessionnel des Vins de Bourgogne gathering. Of course, no critic would dare blind taste and score certain domaines for fear of giving accidental poor marks, which they might be tempted to alter once revealed for fear of dismissal from their readers, or a cold welcome from the celebrated winegrower on the next visit to the domaine. While so many well-made wines are analyzed in minutes, or seconds, in a snapshot with no personalized fluffing and far too early in the wine’s development, others have them isolated for the pitch—pharmaceutical sales 101. I’m fortunate to still drink the two elites from Chablis here and there because of my regular visits to the appellation, where restaurants are forced to sell them at fair markups from the cellar pricing or risk losing allocations; no grower wants to see their 15€ ex-cellar premier cru sold for 200€ on a wine list in their hometown. There are also a few hidden restaurants in France, or close to it, with relatively fair prices on the Big Two. In the past, wine pros would say, “I love Chablis!” But when you’d peruse their list, they only had the Big Two on the bottle list and something else on their glass-pour program. Is that a true love for Chablis? Or, at the time, just a love for the cheapest ticket to extraordinary white Burgundy?

Sometimes blind tasting is useful. Sometimes it’s not. Five minutes of excessive swirling, exhausting the wine and your palate as you try to discover its clues … The best outcome? When we are wrong … especially after we were so certain, it’s humbling. It’s always a test of what we think we know—a harmless learning experience, though maybe not so great for the ego. Sometimes we look like a boss. Other times, a World Market wine department specialist—no offense: ya gotta start somewhere! And sometimes we’re not humble enough in spirit and develop an immediate negative bias that, sadly, can stick around when we’re wrong. “No, not me,” you say. Never … “Oh! I should’ve said that … I was going to say that!” Or, “I can’t believe that’s that. It doesn’t have X, Y, and Z (otherwise I’d have nailed it). The post-mortem play-by-plays are often best left unsaid.

Blind tasting doesn’t work well with Chablis. Especially within only five minutes of opening it … Chablis is a journey, and the best may seem spare at first, sometimes even awkward. If it outshines others in a blind tasting within the first ten minutes, maybe there’s something more off than on. Most compelling Chablis start and remain snug, withholding, and can even be Willy Wonka quirky. And in an instant after waiting, almost pressuring it to perform, they strike deep into its Kimmeridgian limestone marl, the salty brine now rising to ocean’s spray, the phenolic blob now cutting minerally textures and acidic flare. No worthy Chablis is as quick a read as an Instagram post.

By the very nature of this region’s wines, its best traits can be slow to get out of first gear. Like with any serious wine, depth takes time to discover. Analysis in a minute, six months after bottling for a few minutes of swirling it to death? Folly. So many Chablis just won’t give their all so quickly—whether just uncorked, or within the first two years after bottling. It ain’t Côte d’Or nowadays, where an immediate blast fizzles quickly or grows into a sixth-gear, high-rpm hum but rarely goes to the salty clouds of the taut Chablis. If there’s any blind-tasting category with the greatest probability of missing the wine entirely, it’s Chablis. So, congrats to Sébastien and Romain for scoring some solid 80s with their AOC Village wines when tasted blind at a BIVB events by critics.

Sébastien Christophe

Romain Collet

We tasted with Romain Collet out of the various vats they employ to highlight each cru’s qualities: Montmains in steel to memorialize the edges of its rocky terroir; Vaillons, with its brown but light textured clay and rocky topsoil, aged equally in 20-year-old 85-hl and 228-liter French oak, a great balance of vat choices to gently “sculpt the clay” and preserve the strong minerally compaction of Vaillons, the wine of their range that helps me best understand each vintage; the exotic Fôrets nestled up in its furthest western part inside a small heat-trap amphitheater raised in an egg-shaped concrete; the remaining 1er Crus—Butteaux, MdM, MdT, and grand crus, Valmur and Clos, all in more marne-rich (calcareous clay) topsoil—in variations of two-to-seven-year-old 228-liter French oak barrels (none new) to sculpt the clay once again. No matter what Romain employs in the cellar, each wine speaks its truth.

There’s some new excitement from Collet labeled ‘Vallée de Valvan,’ but it hasn’t arrived yet. If you look at a map of Chablis, there is a “village” section of the backside of Montmains facing northeast, mirroring Vaillons and most of Vaillons is inside Valvan. I asked Romain since my first visit with them in 2010 about this long stretch of vines they have that makes up a good chunk of their AOC Chablis. It seemed obvious and still does, that it has the same geology as its neighbors. When they classified the area the southerly exposure needed for premier cru classification was missing eighty years ago, but the soil was premier cru. But things have changed, and these “less favorable” expositions can now chalk that up as an asset, and that’s clear in this minerally fresh new bottling. Collet’s Vallée de Valvan represents Chablis’ future.

We finished our day at the Richoux’s cellar in Irancy. We work with the Richoux family only in California and a few other states, but Remy needed to meet them and their wines as they’re one of the central pillars of our company’s French portfolio. Our first imported vintage from them was the 2005 Veaupessiot and 2007 Irancy. Since Gabin and Félix were given more input into the production, things have changed a bit from a more rustic, classic, striking and clean style raised in 55-85-hl old French oak foudres to something more in line with a Côte d’Or style, smaller barrels with some a little newer than the past. The first moment for their cellar filled with 500-600 L barrels was with Thierry’s “Ode à Odette,” a unique wine made in honor of his grandmother who used to work a certain parcel of ancient vines. Seemingly on a whim, they bought a massive batch of new barrels and aged it for three years in them. Well, then they had to do something with all these leftover barrels! The Richoux boys also experimented with softer extractions and withheld sulfite additions until the bottling. These changes resulted in much more fruity wines but it was harder to understand all the changes at the time because the seasons were going haywire and particularly impacted Irancy.

Fast forward to 2019 and 2021, two of their finest vintages demonstrating the balance of those changes. 2019 is richer, as the season was warmer, but balanced with denser fruit and well-managed alcohol levels still around 13.5%. While the 2019s may be the crowd-pleaser between these two vintages, the extremely low-yielding 2021s are nearly perfect wines for my preference: elegant, lifted, red-fruited, finely structured, fresh, floral, and without any impression that the sun abused a single berry. After the cellar tasting and the open bottles of 2019 and 2021, we tasted and tasted and tasted, Remy became a deep believer in the mythology of Richoux. Our first shipment of the 2021 Richoux Irancy wines will arrive in California this month.