As this hits your inbox I’ve hopefully caught a bus from Barcelona to meet my wife in the Catalan seaside town, Sant Feliu de Guixols. This historic fishing village doesn’t make it easy to curb excessive consumption, with its daily outside market of dozens of local farmers who have all the seasonal fruits and vegetables you could want, three fish markets brightened by the glass-clear eyes of the freshest fish and the famous local Palamós red prawns and the cheese purveyors inside the historic Mercat Municipal building and half a dozen butchers with an immense selection of beef cuts from all over Spain (including the famous Galician beef chuleton), Iberico pork (cured and every fresh cut you’d ever want), all only 150 meters from our door. With only a few days to run off the well-earned weight I’ve gained while in Piedmont and Southwest France, I won’t make a dent before I’m off to Sicily for producer visits and the Catanian restaurants responsible for some of my most memorable meals.

My last trip to Catania was five years ago. It was short and I missed my shot at attending the frenzied fish market down by the port. It’s been more than a decade since I savored the perfect and simply prepared fresh seafood in a cozy spot in the middle of the chaos—I think the place was called “mm! Tratoria.” It’s a touristy area, but if there’s one place to have extraordinary seafood in a touristy spot, it’s there. I’ve had a lot of noteworthy food experiences in my life, but Catania and its market have become part of my personal food and culture mythology.

We have a new producer from Etna that I’ve yet to meet in person. My usual modus operandi involves a visit to the cellar and vineyards before working together, but the Nerello Mascalese wines of micro-producer, Etna Barrus, were emotionally striking every time I drank them over a few months, so we skipped protocol. When I get to Sicily I’ll dig into the sands of Vittoria and turn over some more Etna tuff to see if there’s another Sicilian grower waiting for us.

This last wine-country sprint started in Milan and ended in Bordeaux two weeks later and put me on that bus to Sant Feliu de Guixols. Our close friend and longtime supporter Max Stefanelli joined me. Our first stop was with future legend (mark my words) Andrea Picchioni and his historical but esoteric, unapologetically juicy, and deeply complex Buttafuoco dell’Oltrepò Pavese wines. Fabio Zambolin and Davide Carlone were the next stops up in Alto Piemonte, and just to the south in Caluso we visited Eugenio Pastoris, an extremely intelligent and skillful young producer featured in our next newsletter this month. Monferrato was a quick stop to visit our four-pack of growers Spertino, Sette, La Casaccia, and Crotin, and finally the Langhe to visit Dave Fletcher and two new inspiring Barolo producers: Agricola Brandini, run by the young and ambitious sisters, Giovanna and Serena Bagnasco, whose wines we officially launch next month, as well as Mauro Marengo, run by an even younger talented wine wizard, Daniele Marengo.

A snow-capped, eye-candy alpine train ride from Turin to Chambéry kicked off my first French visits of 2023. The ride was beautiful but on the French side of the Alps the Savoie’s Arc River was concerningly low with little spring runoff. I had a stop with one of Savoie’s cutting-edge growers, then dashed across France through the Languedoc to another new addition, Le Vents des Jours, a former Parisian sommelier crafting wonderfully pure and expressive Cahors wines without any added sulfur. Jurançon had two stops, Imanol Garay, and another exciting new prospect who will remain a secret until our first wines are on the water. Finally in Bordeaux, I visited Mathieu Huguet and his Demeter and AB certified micro-Bordeaux project, Sadon-Huguet, with its full-of-life, pages-of-tasting-notes Merlot (60%) and Cabernet Franc (40%), Expression Calcaire—à la Saint-Emilion! I admit that I’ve always had a soft spot for the old right bank Bordeaux, particularly Pomerol, but, of course, when someone else is buying! Those I loved are well out of my range and older than I am.

California kicks off in May for my second 2023 trans-Atlantic jump. I’ll get two weeks with our team, my family, Giovanna Bagnasco, the newest Barolo revolutionary at the helm of Agricole Brandini, and attend the wedding of one of my lifer-friends (who’s also my literary editor). Upon my return to Costa Brava, I’ll crack a bottle or two of Champagne with my wife before bed, then jet lag will kick off the usual cycle: Death. Rebirth. Repeat.

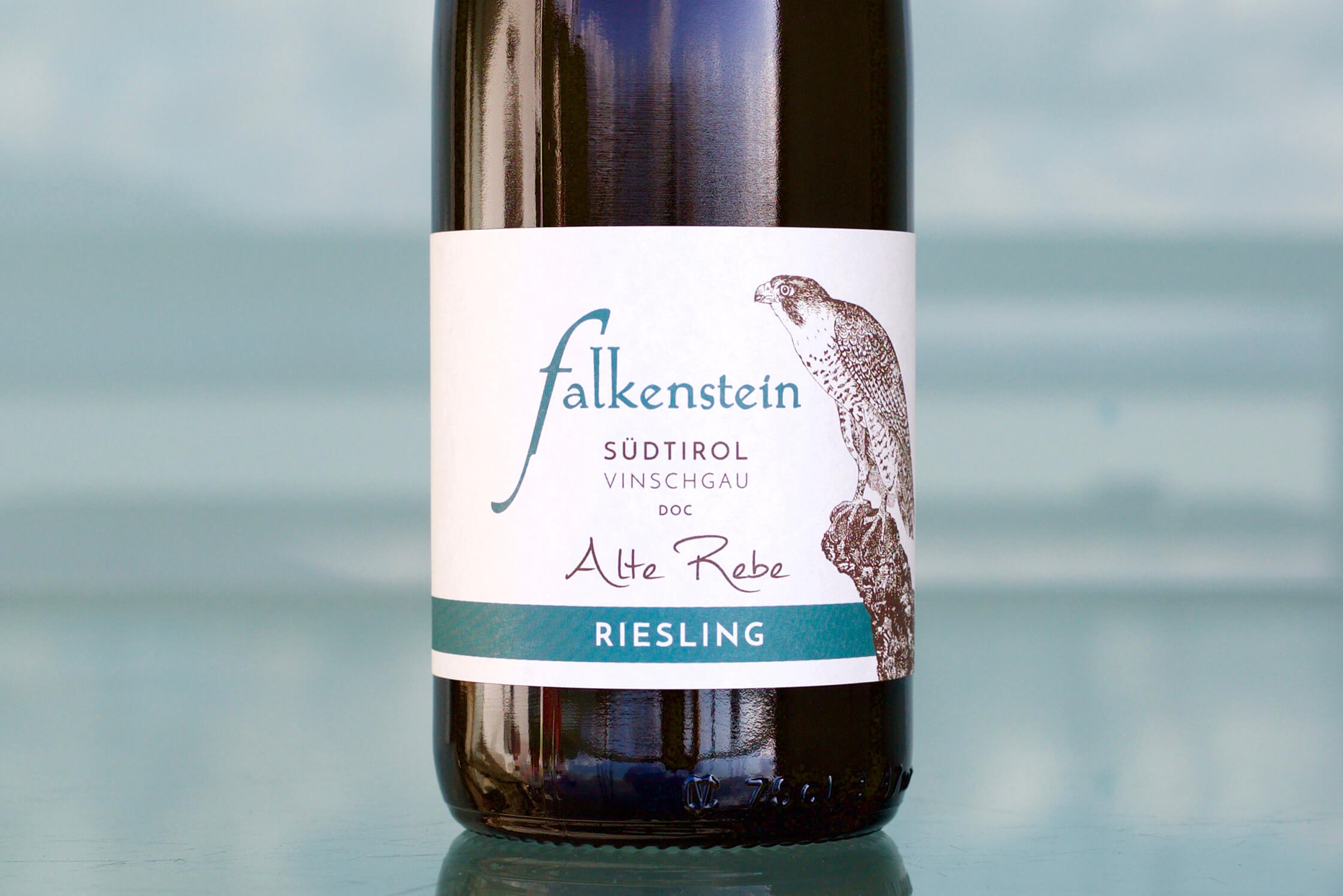

This month we have something from about almost every country we work in Europe, with our newest addition from Champagne’s Les Riceys area, Taisne Riocour, Beaujolais wines from Anthony Thevenet, Portugal’s preeminent Vinho Verde garagiste, Constantino Ramos, Spain’s Navarra renaissance men, Aseginolaza & Leunda, and Italy’s premier Riesling producer, Falkenstein.

Les Riceys, Champagne

I have this obsession now, this little addiction to Les Riceys, its bubbles and still, and Élise Dechannes is to blame. These Pinot Noir wines grown an hour east of Chablis are hallucinogenic, hypnotic, more fun and fantasy than reality, cherubs with love-poisoned arrows, irresistible enchantments of high-toned red fruit and fields of dainty but potent spring strawberries, hints of cranberry, and dry as a bone but with that inexplicable, irresistible limestoney, fairy dusty, powdered-sugary, stardust twinkle. After being open for days they run out of gas but never go entirely flat, often remaining charged, pure with pink and red fruit and fully expressive post pop they can be even better than their former bubbly selves. If there’s a Champagne as good, sans bulles, it might be from Les Riceys. This makes sense of the fame of its most historical wine, a rosé made entirely from Pinot Noir with its own appellation, Rosé des Riceys. Rosé des Riceys is a bit of a unicorn, hard to get your hands on more than a bottle at a time, and it’s expensive. After all, it’s part of Champagne’s Aube and right on the border of Burgundy’s Côte d’Or department—no chance for a bargain!

Our interest in Élise Dechannes was timely. With gorgeous new labels inspired by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry illustrations (Le Petit Prince), people were drawn in and discovered Élise’s soft touch and talent, and interest in her seemed to explode overnight. This forced us to search for more sources in Les Riceys, and one just happened to knock on our door when I was in Austrian wine country last summer.

Taisne Riocour is a new venture by the historic Les Riceys grape growing family, de Taisne. In 2014, the five boomer-aged de Taisne siblings decided to bottle their own wines for the first time since the maison was established in 1837, “not out of necessity, but more of a project to go deeper in the previous work of our parents in the vineyards,” Pierre de Taisne explained. “We also had the will to reveal one of the greatest terroirs of Champagne. Instead of selling all our grapes to be blended away into big house cuvées, we want to show the character of our vineyards.”

A visit to the de Taisne family and their vineyards is ecologically encouraging and rich in familial comfort. While all are parents, and some now grandparents, the three brothers and two sisters de Taisne are addressing the agricultural challenges and ethical necessities of our time. Since taking on this new project, they embraced biodynamic treatments (three of their 21 hectares were converted to biodynamics in 2020 as a trial with the advice of Jean-Pierre Fleury) and a plan for full organic conversion began in 2021. Open to other progressive ideas, they like wind-powered ocean freight liners and want to adapt payment agreements to facilitate this slower but more ecological transit. It’s a small contribution, but everything counts!

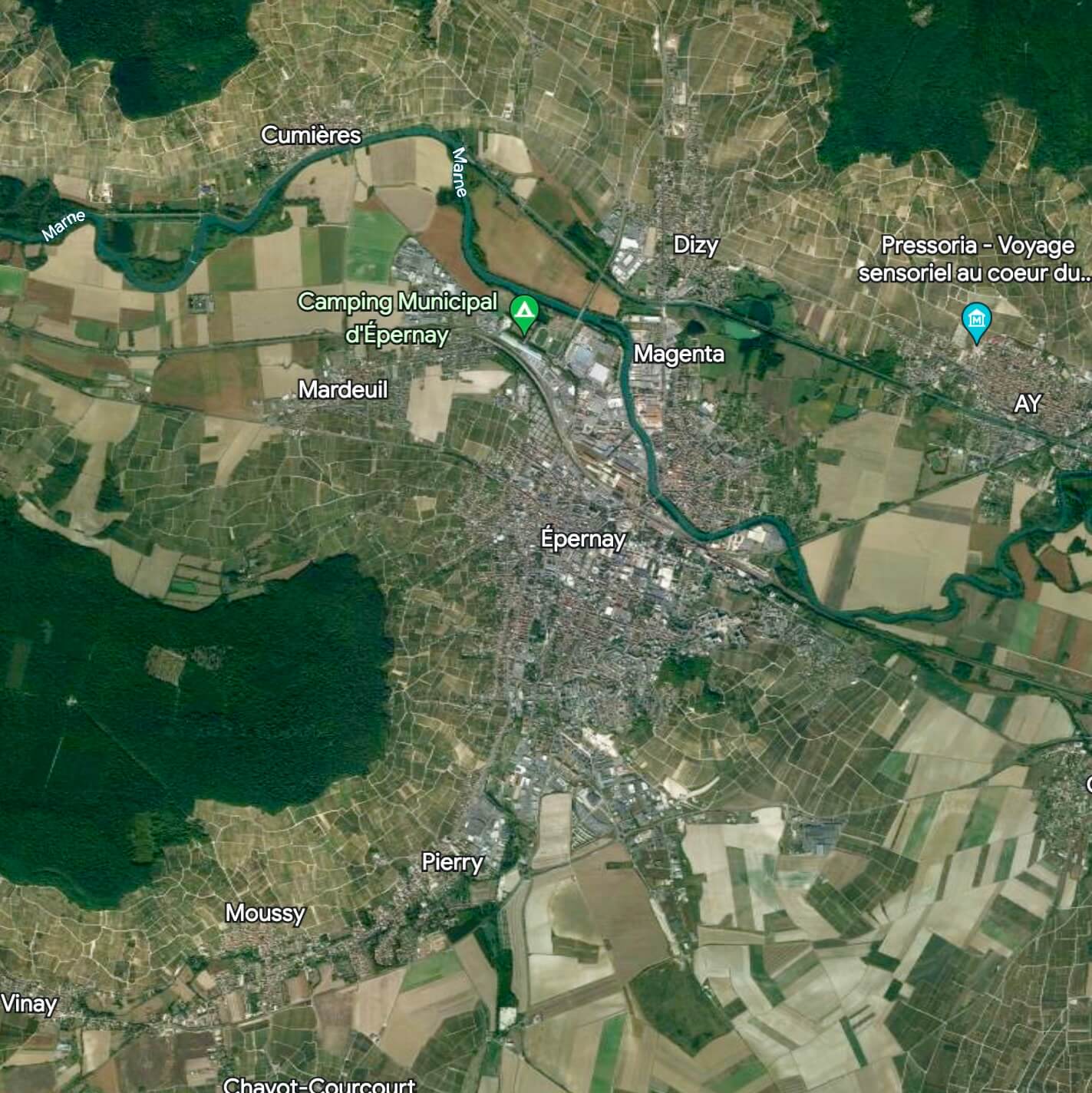

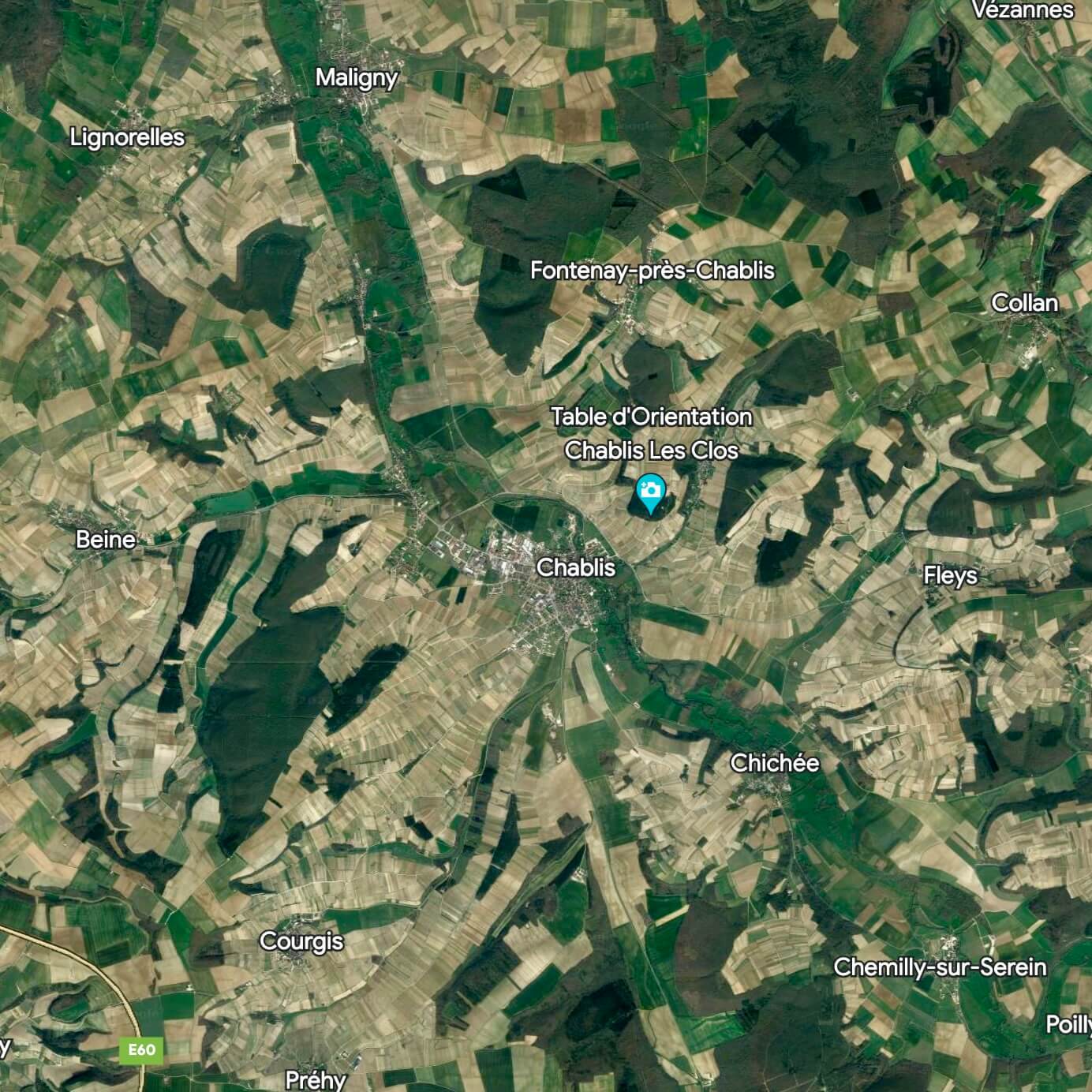

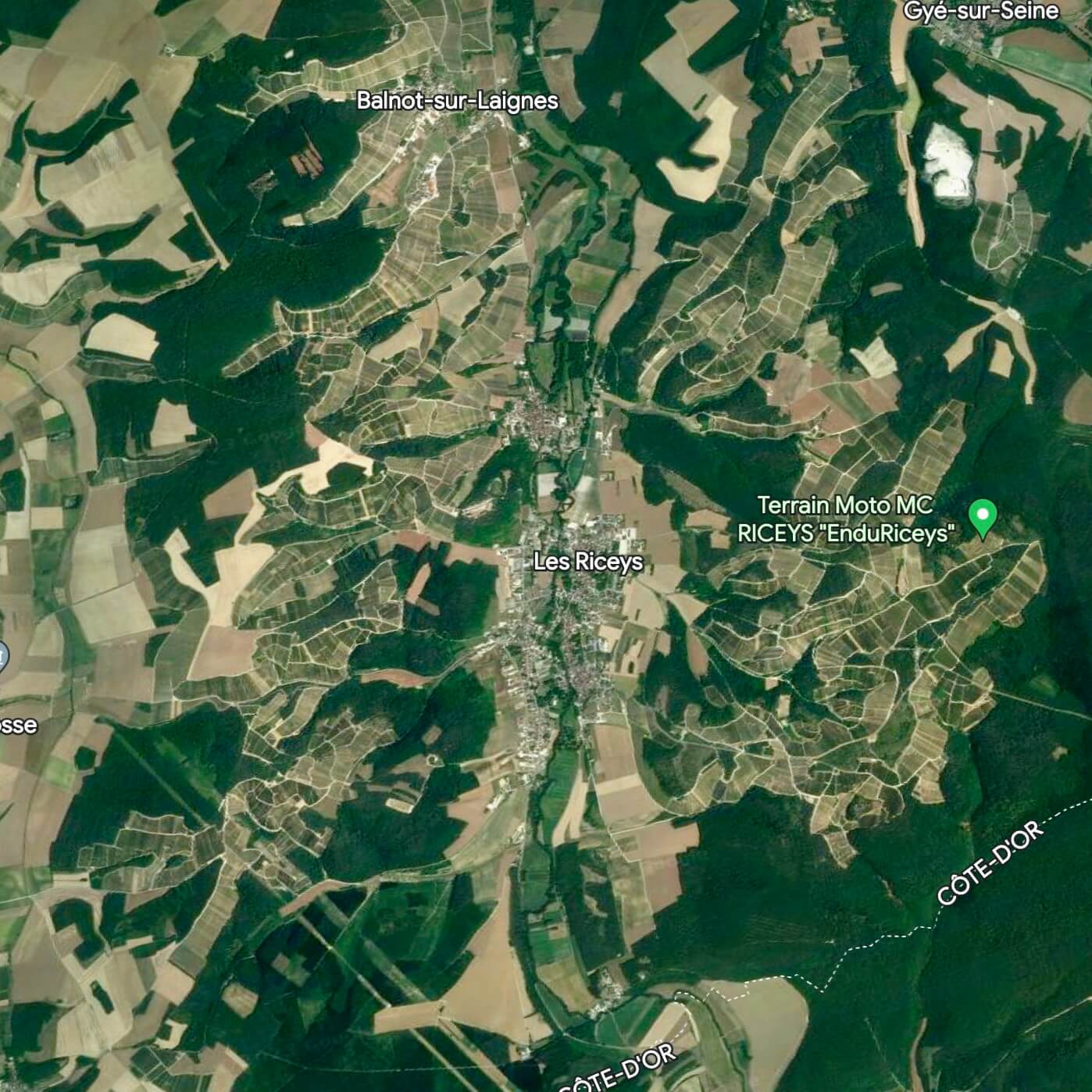

The de Taisnes speak of greater biodiversity objectives by incorporating more non-vinous plants into their land and between rows, though Les Riceys is more heavily forested than many French viticultural areas. Here, it’s not like other famous Champagne territories with vines on every hillside and a vast expanse of other single crop fields that begin where the vines end. Les Riceys and the surrounding vineyards bear some resemblance in topography and town positioning to the neighboring Auxerrois regions. Similar to Chablis and Irancy, the three hamlets of Les Riceys were individually fortified centers with their own churches less than a kilometer apart. Ricey-Haut, Ricey-Bas and Ricey Haute Rive sit in the center of the appellation with numerous hillsides on all sides of the villages, carved out by erosion. But unlike Chablis, where vines grow on all sides around the village with even more Chardonnay vines for Petit Chablis on the plateaus above, all surrounded by endless crops, Les Riceys has many more vineyards scrunched together between wild forests. Les Riceys has little in relation to the heartland of Champagne, and the Google Earth images below demonstrate the dark green forested areas (which are the greatest sources of biodiversity and soil life) in two Champagne areas, Chablis and Les Riceys. All are roughly the same scale on the Google Earth.

Les Riceys and the elusive Rosé des Riceys

When asked why Pinot Noir is preferential instead of Chardonnay, Pierre de Taisne says that though it’s geologically linked to Chablis with similar Kimméridgien marls, more Pinot Noir has been planted in Les Riceys since the 11th century.

Les Riceys is Champagne’s southernmost area, known as the Barséquanais, and borders the Côte d’Or with vines just next to the official lines. Les Riceys changed hands between Champagne and Côte d’Or many times, which helps explain its history of still wine production and Champagne, and the possibility for three different appellations of wine: Coteaux Champenois, Champagne and Rosé des Riceys. Initially the Aube, where Les Riceys is located, was not included in the greater Champagne appellation. Pinot Noir was most suitable in Les Riceys (the monks knew!), and this predates the adoption of bubbles in wine by more than five hundred years.

Les Riceys Pinot Noir first captured the attention of France’s royalty which led to greater European celebrity—particularly notable are the courts of Louis XIV and Louis XVI. The rosés of Riceys also gained widespread fame thanks to strong wine merchants, with the notable example of Jules Guyot, who published a study in the 1850s about French vineyards and noted the high quality of Les Riceys terroirs—pre-local Champagne production. But in 1927, after a strong revolt from growers who were able to sell their Les Riceys grapes to other Champagne regions for Champagne production but were not allowed to make their own Champagne until after 1911 (wineterroirs.com; 2009) and classified as Champagne Deuxième (second), the Aube was finally included in the Champagne appellation (albeit with second-class citizenship), and were now permitted to make their own bubbles. Since there was (and still is) more profit in Champagne than a dark-colored, full but taut, slightly tannic, sharp rosé (the opposite of Provence rosé in almost every way), Champagne production became the focus.

The Team

Because of their centuries of building relationships, the de Taisne family was able to move from grape growing cautiously and carefully to bottling their own with the help of friends. Cellar Master at Taittinger, Alexandre Ponnavoy, helped launch their new project with confidence by helping them define their core principles based on historic terriors that have richer soils than most of Champagne, a warmer climate, and strongly fruity Pinot Noir. The de Taisnes describe their wines as having “regional character with the richness of Pinot Noir aromas, freshness, and an elegant finish.”

Pierre and Charles de Taisne are the family members in charge of the vineyard work, and they’re supported by Enologists Jean-Philippe Trumet and Laurent Max in the vineyards and the daily cellar work. Taisne Riocour also has oversight and other advice from Enologist, Cécile Kraemer, and well-known French Sommelier and Champagne specialist, Philippe Jamesse. What a team!

The Vineyards

The geological bedrock classification of Les Riceys is Kimmeridgian, the same as Chablis, though not exactly the same dominance of the famous miniature oyster-like fossil limestone marls of Chablis. Les Riceys is more similar to Chablis and Côte d’Or than the north of Champagne where bedrock was formed during the Cretaceous and Tertiary and is most famous for chalk. Les Riceys is limestone marl and calcareous mudstones from the Jurassic age, with a more geometric rock appearance than the flaky, friable, fossil-rich Chablis Kimmeridgian limestone marls. Les Riceys’s topsoil is rocky with calcareous clay and silt and very little sand.

Taisne Riocour’s twenty-one hectares of mostly Pinot Noir have an average age of 35 years (the oldest around 65), are on different exposures throughout the appellation on slope gradients from Côte d’Or-gentle to Mosel-steep, range between 250-340m in altitude, and are on both sides of the northbound Laignes River. Tillage is done lightly to a maximum depth of 5-10cm, only to undercut grass roots and is done a few times each season—the same as most limestone-and-clay Burgundy areas. As mentioned, they work some parcels organically and biodynamically, with organic certification processes that began in 2021.

The Wines

Cellar practices are simple and direct, especially in the earlier years to better discover their terroirs and to adapt the direction for each parcel. Fermentation in steel lasts 10-15 days, with neutral Champagne yeasts, and all go through malolactic fermentation. Sulfites are added during the pressing, again at the end of malolactic fermentation, and at disgorgement, with a total that ranges between 40-60ppm (mg/L)—low for Champagne. Everything is aged for approximately five months in steel (25k-200k hectoliter vats) with the exception of about 1% in old oak barrels for the Grand Reserve. The wines are filtered and aged in bottle for three years, with riddling done one month prior to disgorgement.

Taisne Riocour’s Grand Reserve (NV), is composed of 15% vin de reserve, 85% vintage wine with 65% Pinot Noir and 35% Chardonnay—dosage 6.5g/L. These grapes originate mostly from a site known as Val Germain on the right bank of La Laignes (a tributary of the Seine, the same one that passes through Paris), southeast of the appellation, at the highest altitudes in the appellation of around 340m with a multitude of exposures on a medium slope. The topsoil is deeper (50-80cm) due to the flatter slope and the composition of more than half clay and one-third silt. The average age of the vines is fifty years and is usually the last of the appellation to be harvested. Other vineyards include La Fôrets (1ha), La Velue (0.4ha), and a little bit of the famous Tronchois (1.4ha).

Made entirely of Pinot Noir and with a dosage of 3.5g/L, the Blanc de Noirs comes predominantly from Tronchois, one of the most celebrated vineyards in the appellation known since the 11th century when under the direction of the Abbey of Molesme. Here is one of Les Riceys’ most exposed sites with a direct south face, capped by wild forest around 275m and met by forest at the bottom at 215m—perfect grand cru and premier cru altitude if one considers similarities to Côte d’Or. The slope is extremely steep and the topsoil is thin, with 40cm on average. It’s also one of the warmest sites in the appellation. The vines were mostly planted in 1970 (with 50 ares replanted in 2019), and the rest in 1973, 1982 and 2007.

Beaujolais, France

I’ve said it for years: Thevenet is one to watch. His first vintage, 2013, was wonderful but in very short supply. The following was fabulous for Beaujolais: great overall balance of yield and quality. While Anthony’s 2013s were very good, the 2014s were even better. 2015 was hot and he still delivered—they have punch, but are contained and fine. 2016 was hit or miss for everybody, but his hits were solid. Then it was back to the heat in 2017 and continued on through 2018, 2019, and 2020. 2021 was different with a cold season that led to big mildew pressure after a loss of half the production to frost. 2021 is hit or miss too, but Thevenet did not miss. We’ve been waiting for this.

The difference today between vintages teeters on a knife’s edge between too much or too little. With extreme changes in short periods, wines easily overshoot their mark in a day or two. 2021 is short in supply, but the results from Thevenet are absolutely wonderful.

Thevenet Cellar Notes

All the wines are vinified with a carbonic maceration without any sulfur added until just before bottling, and they ferment at temperatures no lower than 16°C. There are no added yeasts, and the fermentations are done in a gentle, infusion style, and can last between eight to thirty days, with the latter more rare and only employed for the top wines. There is no fining or filtration, and the total sulfite levels are under 15mg/L (15ppm). The purity and clarity of each wine’s terroir expression under Anthony’s supervision due to very spare sulfite inclusion are a testament to his laser-sharp attention to detail and instinct.

We were able to nab a few more boxes of the 2019 Chénas Village and 2019 Morgon Vieilles Vignes, so don’t sit on your hands here. This season created full and delicious wines and these are two highlights of the vintage (the reasons we asked for more!).

Like 2020, the 2021 Beaujolais-Villages presents an opportunity to see the merit of Thevenet’s lovely Beaujolais range and what a perfect year for a wine with streaky red fruit and tension. Thevenet’s 2021 Morgon appellation wine comes mostly from Douby, a zone on the north side of Morgon between the famous Côte du Py hill and Fleurie, and the lieu-dit, Courcelette, which is completely composed of soft, coarse beach-like granite sands. Many of these vineyards are on gently sloping aspects ranging from southeast to southwest. There are also rocky sections, but generally the vineyards are sandy, leading to wines of elegance and subtlety, also endowed with great length and complexity from their very old vines. The average vine age here is around 60 years, not too shabby for an appellation wine!

Once it’s in your glass it becomes obvious why Anthony bottled his newest cuvée, 2021 Morgon “Le Clos,” instead of blending it into other Morgon wines. Discrete and fine with a north-Chambolle-esque structure, body, color, and lifted perfume, its red fruits, citrus and a touch of stemy green lead the way for this young wine born from twenty-year-old vines on granitic bedrock, clay and sand. After ten days of carbonic fermentation, it spent six months in older (with just a hint of fresh-cut wood), fût de chêne (228l barrels). This effort by Anthony is his ninth vintage since he first started bottling his own wines in 2013, and his fifteenth or so vintage in all (including work with Georges Descombes and Jean-Marc Foillard over five or six years) demonstrates his mastery of craft and maturity as a winegrower.

Anthony makes the 2021 Morgon Vieilles Vignes Centenaire exclusively from the ancient vines in his Douby property just above the D68 on the north side of the hill across from the fields surrounding his family’s home and old cellar. This latest release is the continuation of wines from extraordinary survivors that date back to the American Civil War! What an opportunity to taste wines with such history, and what a vintage to do it. Like the Morgon Vieille Vignes, it’s aged in 600-liter demi-muids, but for around ten months. It’s spectacular and offers a different view into how vine age can truly influence a wine’s overall character. If wine critic Neal Martin says the 2017 version “would give many a Burgundy Grand Cru a run for its money,” then imagine the 2021… It’s off the charts. Elegant and profound. Bright to garnet red, great texture. With clear potential to last forever and improve with cellar aging. Once open it’s fresh for days and builds on its strengths. If Thevenet’s Le Clos is Chambolle-like, this is Ruchottes-Chambertin fruit, tension, and caliber. As one would expect, supply is very limited.

Vinho Verde, Portugal

Shortly after our first contact with Constantino Ramos, his wines exploded in Portugal; we clearly got in at the right time. At the beginning of last year, he left his post as Head Winemaker at Vinho Verde’s most famous and progressive producer, Anselmo Mendes, and these days he’s touring the country consulting for half a dozen growers in Dão, Bairrada, and Azores. He can also be found on television cooking shows, doing wine events, wining and dining with inspiring wine writers, winning new fans all over, including us and our customers in the States. Only twenty-five minutes away by car from our apartment, there is no person in Europe, other than my wife, that I spend more time with than Constantino. Cooking and wine tasting and drinking is an every other week event for us, at least when I’m home.

There are two new wines we’re importing from Constantino. Guided by the region, his former mentor and boss, and his passion for Spanish Albariños, particularly from Salnés, it was natural for him to start his winemaking project with Alvarinho (aka Albariño). His is called Afluente, which is in reference to a stream passing by, not because it’s made solely for affluent people, or because it’s expensive—it’s not. I’d tasted many vintages of this wine before and all were good, but the 2020 Alfuente Alvarinho turned a corner and we had to bring some to the States to further share his talent, despite the miniscule quantities available.

Constantino describes this season as balanced, with good sunlight and the right amount of much-needed rain at the very end of July, which helped a lot after a dry June and July. It’s harvested from a single vineyard situated 200m altitude in Melgaço’s Riba de Mouro hamlet, all part of the greater Monção y Melgaço subzone of Vinho Verde, and generally much higher in altitude than Monção. Constantino believes this to be his best effort to date, and while the others were also very good, I’m as convinced as he is. Once pressed, the juice is settled for a day then barreled down in 500l old French oak barrels with no added yeast. In the barrels the temperatures peak around 20-21°C, which develops wines focused more on mineral and savory characteristics than fruitiness. Because this is further inland than Albariño areas like Salnés in Rías Baixas, which is almost entirely within view of the Atlantic, the wines are more influenced by a continental climate, resulting in a full-bodied white with broader shoulders. In 2020, Constantino sculpted and trimmed these shoulders into a much more delicate wine for this famous Portuguese Alvarinho region. Sadly, we were only able to squeeze him for about nine cases this year because we were very late to the game on this wine.

Despite the amount of time we spend together, we don’t talk a lot about his wines or my import business, as there are so many other interesting things and other wines to talk about. When my staff visited with him this last spring (and became the newest members of the Constantino Ramos Fan Club), they pleaded with me to buy his new wine, 2021 Juca. Juca? Great name. Great label. Never heard of it… I thought, “Seriously, Constantino? Not even a mention over the last six months of dinners together?” (Obviously not acknowledging what I just mentioned about our usually not talking shop.)

Once I tasted it, I understood the plea from my reps: it’s delicious. It also comes from a surprisingly special source, and for the money, that makes it an even more ridiculous deal. In August 2021, one month before harvest kicked off on the white grapes, Constantino’s cousin told him about a vineyard high up around 400m (about as high as it goes in these parts to get ripeness, especially with red grapes) with what they believe has 100-year-old vines. Surrounded by forest and well away from any highway and accessible only by foot or small tractor, he bought the fruit; he simply had to. Instead of putting this intriguing new vineyard’s bounty into Zafirah, Juca, named after Constantino’s wife’s grandfather, was born. It’s a field blend of Caiño Longo (Borraçal in Portuguese), Brancellao (Brancelho/Alvarelhão), Espadeiro, and Sousón (Vinhão), and has one week of soft punchdowns by bare hand one time per day during one week before being pressed and followed by 7-8 months in 30% old barrels and 70% steel.

While Juca was harvested on October 8th, the grapes were collected for 2021 Zafirah from its five different parcels between 200m-250m also in Riba de Mouro, on October 5th. It spends a single day of skin maceration before being pressed, followed by seven to eight months in 30% old barrels and 70% steel. 2021 was a very cold and wet summer with a lot of cloud cover. Constantino describes the reds as more vertical in style, more savory and with balsamic notes—both typical of the red wines here. Zafirah is also roughly the same blend as Juca but expresses its terroir in a more discreet way than the nearly flamboyant and stronger flavored Juca. I guess in the vineyard parcels they had a formula long ago that worked well with these four varieties that are co-fermented with bits of other grapes.

Navarra, Spain

Environmental biologists and former winemaking hobbyists, Jon Aseginolaza and Pedro Leunda, have taken on the colossal task of trying to better the image of Navarra and bring back its former notoriety, when it was once considered the equal of Rioja, centuries ago. They are indeed making strides, but the Tempranillo tide that washed away most of the Garnacha in this part of Spain, and the ubiquity of Garnacha in Spain and France, makes it a tough fight.

Grenache seems to perform best in the market as either cheap and cheerful on one end, or serious wine in need of cellar time. In between seems like no man’s land, even if the wines are very good. Those made in a simple way with higher yields are fruity and sometimes have less alcohol. And those in search of cellar immortality from places like Gigondas and Châteauneuf-du-Pape can be simply mesmerizing with lengthy cellar aging, especially when alcohol levels are modest when compared to today’s alcohol monsters. It’s much easier to understand the true greatness of this noble grape after decades of cellaring when its youthful vigor and solar strength gives way to nuance and refined elegance; it’s no accident that Châteauneuf-du-Pape was France’s first official AOC. Most young Grenache wines between value and vin de garde seem lost in a sea of full-bodied, strong reds that lack compelling distinction.

Not an exception to these conditions, Jon and Pedro’s wines tend more toward the vin de garde category, though they’re approachable compared to many of today’s sun-soaked top wines of the Southern Rhône Valley. The fruit quality of their wines between 13.5%-14.5% alcohol is fresher and more savory than sweet, and still full in flavor—ideal for full-flavored fare.

Jon and Pedro approach their wines as a project of rediscovery more than one of brand-building to sell more and more boxes. Even though they hadn’t made wine prior to their project, their wines have been impressive from the start, and they continue to build on their early success.

Jon describes 2020 as a warmer vintage than the average year, but a wet spring gave much needed water reserves to the start of the season. June was cool and rainy, July was dry, and August returned to gentle rains and higher humidity, defining the 2020s as full yet fresh, with tense, energetic fruit. The 2020 alcohols range between 13.5%-14.5%, the same average found in Italy’s top Nebbiolo appellations, and even lower than many 2018-2020 Côte d’Or Pinot Noirs.

When I visit Navarra, Rioja, and Provence, I pick and fill my car with bags full of wild thyme to dry and separate later. Thyme here is more powerful and gamey compared to the wild thyme I’ve picked in Provence—like the full flavor of jamón Iberico compared to French saucisson—and it often smells as much of lavender as thyme. I love lavender but it’s hard to incorporate it into recipes because of the bitterness and texture of the buds. (That said, I suggest putting the stem, buds, flowers and all inside of a whole duck set to be roasted; it works for chicken too. The duck fat is infused with clean and intoxicating lavender scents, and lavender duck fat on roasted potatoes is the next level.) This thyme is so strongly scented with lavender that it’s a perfect, though subtler, stand-in. All of Jon and Pedro’s wines are marked with this gorgeously pungent and aromatic thyme/lavender and other wild aromatic bushes—French garrigue on steroids!

The first of the four is the 2020 Cuvée, made from 85% Garnacha and 15% Tempranillo from several vineyards at 445m-535m altitude, grown on clay, sandstone and limestone conglomerates. It’s fully destemmed for fermentation and afterward pressed and aged ten months in old French oak barrels. Jon notes that this wine’s general disposition is a mix of black and red fruits, garrigue, and good mineral drive. The 2020 Cuvée Las Santas is made from 100% old-vine Garnacha from several plots (445m-655m) on calcareous clays. 50% whole bunches are included for fermentation, followed by nine months in old French oak. It has lower alcohol than the others, at around 14% (the other three are 14.5%), and is dominated by red fruits (love that red-fruited Garnacha!), spices, aromatic herbs (you know the ones!), and it has a distinctly minerally character.

The two top wines come from very old single parcels. There are others too, but to have them side by side is interesting and perhaps more distinguished because they are led by different grape varieties in their blends. Camino de la Torraza (2020) is made of 70% Mazuelo (Carignan) and 30% Garnacha grown at 380m with vines planted in 1960. The soils are very poor (perfect for complex wines) and composed of clay, silt, gypsum, and conglomerates—similar to some top terroirs of Italy’s Nizza Monferrato. Whole clusters (25%) are incorporated and after pressing it’s aged for ten months in stainless steel. Jon notes that it always has Mazuelo’s classic purple flower aromas and slightly higher impression of saltiness, perfect for food matching. Because La Torraza is mostly Mazuelo, it’s quite different from all the other wines in this Garnacha-led bodega.

Last in the lineup but always first for me in the range is Camino de Santa Zita (2020). It’s 100% Garnacha grown at 545m from vines planted in 1926 on two calcareous clay terraces. It’s x-factor heavy and has the greatest depth with elegance in the lead role. It’s also the vineyard that started their project, and I can see why they would want to make wine if this vineyard was that genesis. If vortex energies tied to locations are real, Santa Zita surely would be one of those places. Its wine is aromatically lifted a touch with the 20% whole bunches in the fermentation followed by eight months in old French oak. Jon notes that it is usually filled with scents of aromatic herbs, balsamic hints, and is round, fruity and minerally. That’s a serious oversimplification, but a good start. This wine is deep.

Südtirol, Italy

An Italian cantina with Austrian heritage, Falkenstein is in Italy’s Südtirol/Alto Adige and produces many fantastic different wines (Weissburgunder, Sauvignon, Pinot Noir—all grapes that have been cultivated here for centuries) and many consider the Pratzner family the most compelling Riesling producer in Italy. The vineyard and winery are in one of the many glacial valleys in the north of Italy’s alpine country, with a typical relief of a flat valley floor surrounded by picturesque steep mountains, which creates starkly contrasting shades and colors throughout. Vineyards in these parts need full exposure on northern positions with southern exposure to achieve palatable ripeness. The vineyards here are some of the world’s most stunning, and it’s surprising how many are tucked into the valleys of Trentino (the bordering region to the south) and the Südtirol. We’re taking in two vintages at once of Riesling because of the small quantities allocated to us with both years. The 2019 & 2020 Rieslings show the skill of the Pratzners and how they manage in difficult and warmer years. Sauvignon from these parts can be intense with a strong and compact core encouraged by the strong diurnal swing from day to night during the fruit ripening periods of summer and fall, making for a 2020 Sauvignon with clean fruit lacking any off-putting pyrazine varietal notes and more focus on shades of lemon preserves and zest with aromatic and sweet white mountain flowers.