We have a new member on the team in the form of a high-flying piece of technological plastic with intricate circuitry and a nice camera. The most difficult part of the drone is realizing long after I’ve left a location only to see how poorly I may have filmed, and by then, having no time to go back to redo it! Nonetheless, despite my bad but slowly improving piloting skills, I managed to take a lot of nice footage along my most recent European trip. Of course, I plan to share it all, but I move at a glacier’s pace with the editing. Filming is the easier part, but it’s also stressful losing focus for just an instant, leading to disaster by ruining a take, or the machine itself. Flying is fun (and the producers love it!) despite the difficulty of trying to capture images while peering into a small iPhone screen with the sun’s glare while testing the dexterity and soft touch of my frozen and often twitching thumbs on the Nintendo-like controller. Piloting the drone is the only moment I regret not spending a little more time playing video games (not something I ever thought I’d say), and I haven’t touched them for three decades.

I hope to share some decently edited drone footage with narration sooner than later, but most will have only music and written commentary. They’re not going to be perfect, but hopefully at least they’ll be effective learning tools; After all, I’m not a film guy, I’m a wine, food and travel guy that wants to share everything with everyone. The purpose of the drone films is merely to offer an unusual point of view with useful information, not just eye candy.

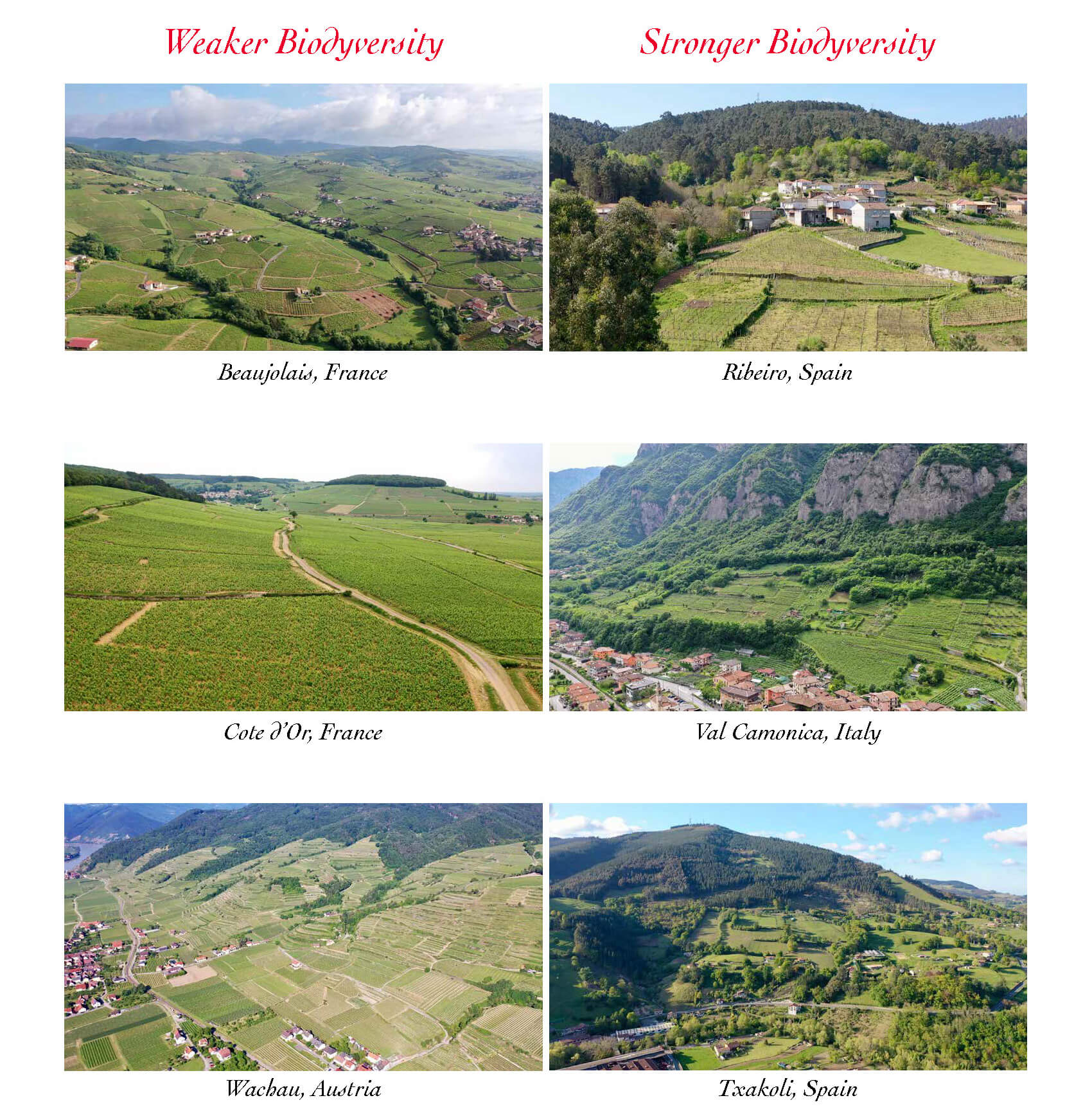

It seems patently obvious to state that the drone brings a vastly different perspective. While standing in vineyards there’s too much to take in and it’s impossible to capture the bigger picture the way a drone can. Another possibly obvious statement: a wine’s characteristics are not solely a microcosmic reflection of its particular vineyard plot with its vine material, dirt and bedrock, and the winegrower’s choices; it’s a reflection of an entire ecosystem with many influencing factors. Each system can be virtually dead, or rich with life in a wild, natural setting, or somewhere in between. Ecosystems don’t flourish and function properly within monoculture environments, and unfortunately, most of the world’s most famous regions tend to be more monocultural than polycultural. The drone reveals this with startling clarity; and by the way, just a few olive or hazelnut trees in the vicinity doesn’t qualify as balanced biodiversity.

When a vineyard’s surrounding environment is treated respectfully and the landscape is truly diverse, or even better, completely wild across most of the land, there seems to be a greater level of x-factor in its products beyond the predictable nuts and bolts. Are those x-factors microbiologically and macro-biologically influenced, or are they just a result of the grape variety, vine material, topsoil composition, bedrock, and the vigneron’s cellar and vineyard philosophical practices combined with the alchemy of fermentation? Are wines with more fruit characteristics than savory ones a potential result of a stronger monocultural influence or because it’s grown in a naturally barren environment, such as the desert-like conditions in some parts of California, Chile, or Australia? Is Nebbiolo from Barolo or Barbaresco more fruit forward than that of Alto Piemonte, partly because most of the prized areas are blanketed by vines and little else, while much of Alto Piemonte is still surrounded by wild forests? Is this a factor when the top regions of Chianti Classico lose critical and popular favor because they can be more savory on the average when compared to many Brunellos surrounded by little else than more vineyards? What about the Côte d’Or’s main slope appellations surrounded by vines on all sides (other than a bordering road or possibly a forest on the very top of the hill), compared to those to the west up into the Hautes-Côtes areas of Burgundy in more forested areas? And Champagne’s Côte des Blancs (whose vineyards look like a nuclear testing site where only the vines and buildings survived) compared to the backwater polycultural zones of much of the Vallée de la Marne?

Biodiversity seems to accentuate complexity, breaking it from a squarer mold and into one more rounded and intricate. I can’t remember if I read it or someone said it to me, but the comment was, “Fruit in wine is like disco in music.” I’m not particularly a music guy, but the analogy is effective, and quite apropos for the current fashion. I also love fruit in my wines, but in any great performance, whether it’s film, literature, art, music, or wine, there is always nuance that brings the actual depth to the performance, even if you don’t recognize it at the time. Without nuance, it is not long before things become dulled and boring.

So what constitutes the difference in taste, shape, and the particular tangent of nuance? Perhaps the overall health of an area’s entire ecosystem should be credited as much as the vineyard itself? Of course, there are many organic or biodynamically farmed vineyards inside of these monocultural regions, but given they may be surrounded by death on all sides, there seems to still be something missing. I doubt I’d get much pushback on that comment from any biodynamic winegrower. They understand the most effective biodynamic environment extends well beyond the confines of their vineyard parcel. After all, this is one of the cornerstones of biodynamic philosophy.

It’s not only a whole new world four hundred feet above ground (the legal altitude limit from drones), but even at only twenty feet. Just as I found it difficult to travel without a geologist in tow after my first tour with the now famous Burgundy geologist, Françoise Vannier, leaving the drone home seems to be a missed opportunity to highlight yet another view into the bigger picture.■