I went down to the kitchen on the morning at La Fabrique and there was a huge pile of baguettes that Sonya had brought from the baker’s long before I woke. It was a heaven of the best bread in the world and I wanted to just hug all the loaves to my chest like a cluster of little friends. Half of them were the thinner version known as ficelles, and she said these were her favorite; the smaller diameter changes the ratio of crust to inner bread flesh, for a chewier, crispier bite.

I took large samples of each and ate them with a pile of scrambled eggs. Again I was met with quizzical looks from the locals and razzing from Ted, as I continued this morning ritual throughout my trip. Ever the gracious hostess, Sonya made sure I always had enough eggs for every breakfast and even showed me to a distant third kitchenette where she had a stockpile in the fridge. I ate alone in a small second dining room full of dark wood and family heirlooms. It was right next to the second kitchenette with the Nespresso machine, from which I took four or five shots, and it was clear of smokers, who preferred the sitting room across the hall or the big table outside.

The patio was crowded with the same people who were at dinner the night before, in the same seats, as if they had never gone to bed. Cigarettes smoldered in fingers and in the ashtrays clipped to the table edges, as bottomless cups of Nespresso were emptied and refilled again and again. The smoking never stopped and took a little getting used to; I laughed when I went into the bathroom the first day and saw an ashtray on a small table beside the toilet, two bent white butts protruding from its center, under a window with a view of a green field where pranced three beautiful horses.

Everyone was busy at work prepping for dinner. I took a seat beside Pierre and he showed me how to cut the stems off small violet artichokes then pull off the outside leaves so that only the hearts remained. Three of us did this for about half an hour, dropping each one into a huge bowl of lemon water. I was glad to be part of the process, even though Pierre kept gently admonishing me for cutting off too much of the vegetable until I finally got the hang of it.

Roman unloaded ten boxes of white asparagus and Sonya and Nicole set to prepping them and after which they started peeling the husks from the long artichoke stems we had cut off (nothing was to be wasted). The French folk rock group Louise Attaque blared through a Bluetooth speaker, and I picked up snippets, including a chorus that sounded something like “do you love me?” We were a quiet, efficient team in a meditative zone, with some of whom wer clearly a little more hung over than the others, though I don’t think anyone would admit it.

I went to retrieve Ted in the guesthouse and found him and Andrea resting after another run. They were discussing some sort of snafu with business back home and she was at the breakfast bar typing frantically into her laptop. As I joined Ted over by a wardrobe where he was absently looking for a sock, he started a diatribe on something that was bothering him: the need for self-promotion that is necessary in his business but requires a level of vanity and intrusion into his personal time that he just doesn’t feel capable of or drawn to.

Some of his peers love to post selfies all over social media, spouting empty aphorisms with piles of hashtags. These are the guys who get the most attention with all of their self-aggrandizing, when what Ted most wants to focus on is the promotions of his producers. His company now works with well over one-hundred domaines between France, Italy, Spain, Austria, German and Portugal, and he goes far and wide to taste wines made by vignerons that nobody in the states has heard of. He shouts their attributes from the rooftops and sometimes it takes a while, but almost all of his bets have paid off.

The wine industry is filled with some pretty big egos, and a lot of these people are afraid to take risks to protect their reputations. Ted regularly goes out on a limb and is often dismissed outright, like when he started to focus on dry Riesling from Germany in California and pitched them to a restaurant in Beverly Hills, the wine director laughed at the prospect like he was crazy. The following year the same buyer began to ask for allocations of a bunch of the same wines.

One of Ted’s favorite finds so far is the Beaujolais producer Jean-Louis Dutraive, which happened when Ted visited his friend Eduardo Porto Carriera, a sommelier who left Los Angeles for another opportunity and a newfound love in New York City. Eduardo blind tasted him on a bottle of Dutraive’s wines that had just been imported to New York by one of his role models in the importing business, Doug Polaner. Ted went nuts and at 1:30 in the morning after that night of eating a drinking, he impulsively sent a drunken email in French to Dutraive, a cold-call in his still broken but improving French, and said he’d buy everything that Dutraive would be willing to send him. He said he woke up six hours later with a response from Jean-Louis Dutraive that said he didn’t have much, but he’d be happy to sell him something. Ted has since gone to visit him numerous times each year and they’ve become good friends. His work is harder than it looks most of the time, “but,” he added, “it’s sometimes just that easy.”

Ted, Andrea and I went out to the communal table and everyone had moved on from coffee to pre-lunch aperitifs: pastis and water, scotch and water and scotch and coke (mainly for Roman). I sat back and listened to the wind through the trees and the sonorous French. It was cool and sunny and the air was filled with the sweet smell of camphor the nearby Eucalyptus and the cigarette smoke that I had begun to find more comforting than toxic for reasons I couldn’t explain.

Lunch came and it was as delicious and rich as dinner the night before; there was a salad of walnuts and crisp endive in balsamic, lasagna with veal and lamb, and the much anticipated white asparagus, lightly steamed and chilled with three types of Mousseline sauce (like Hollandaise with whipped cream folded in): tarragon, fennel and garlic. The last one was incredible, like eating an entire garlic clove in creamed form. There was some talk that it got more garlicky each time, spurred on by a challenge issued by someone or another.

Then Sonya brought out a huge tray of tiramisu, this time Roman’s favorite. It was fluffy cream, Madeleine cookies, rum, coffee and cocoa perfection. The chocolate mousse came out as well, the huge bowl still plenty full. I, for one, was about to explode, but I watched in amazement as Ted put away a big pile of it after finishing a healthy portion of tiramisu.

After lunch we were off to do some sightseeing. We left the party refreshing their cocktails under a low hanging cloud of smoke and drove toward Avignon. As we passed through the city, I marveled at the wide expanse of stone buildings surrounding a massive palace, once home to popes needing a break from the Vatican. Only a few miles away was Châteauneuf-du-Pape, the commune where Pope Jean Paul XXII had another palace built during the schism of the fourteenth century.

We continued on toward Les Baux-de-Provence, a tiny commune in the Alpilles mountains. “Mountains” seemed generous; they would be hills in Colorado, where I come from. The narrow road wound through scraggly trees and fields of tall light green grass bending in the wind, with stone blocks like castle battlements standing in for guard rails along the shoulder.

We pulled over at a crest and surveyed a small valley known as Val d’Enfer (the Valley of Hell), pocked by countless square caves carved into the rocky cliffs across the way. There was a pile of stone structures on another tall hill far off to our right, topped with the crumbling ruins of a fortress: the tiny township of Les Baux, a tourist destination that was once home to four thousand and has a current population of twenty-two.

It took us a while to find a parking spot beside the road, now packed with tourists in cars (okay, tourists like us—funny how sometimes only others are silly tourists, while we belong there). Once we got up into the little town, we were swept into a river of gawking families and couples buying trinkets, candy, ice cream, crepes and every other manner of sightseer money magnet. We took in the dusty paths and buildings, all a monotonous, dusty wash of the same yellow beige sandstone, like the whole place was carved right into the mountain—and much of it actually was. The remains of the fort were out of sight, but Ted and Andrea had been there many times before and I felt no need to fight more crowds to see some ruins.

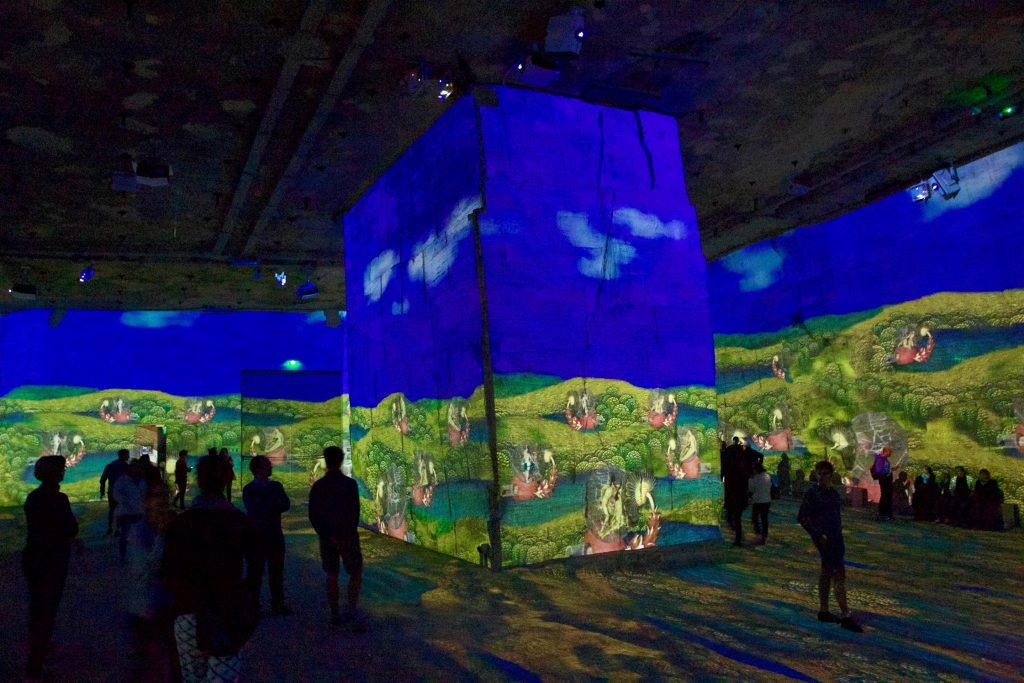

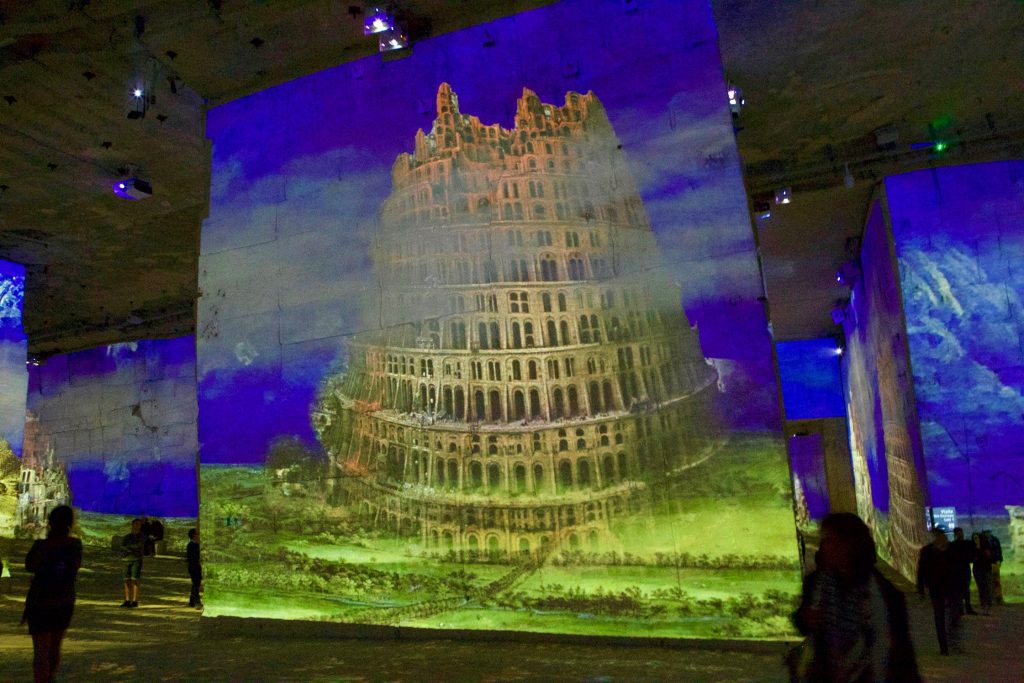

At the bottom of the hill, we found something that I had never seen or heard of: the giant caverns in the cliffs known as Les Carrières de Lumières, or The Quarries of Light—some of the caves we had seen from across the Valley of Hell. Once bauxite quarries from the 1800s, the scale of the place was hard to process. Huge overlapping rectangles had been carved into the solid stone face and the ceiling above the entrance reached to fifty feet. Inside, we were dwarfed by spaces hundreds of feet long and wide, with forty-five-foot tall walls. Every surface from top to bottom acted as a screen that displayed over 2,000 colorful and dizzying images and animation cleverly constructed from stills, thrown there by countless digital projectors. Everything moved in time to sweeping classical music that then built to a crescendo of a French cover of Led Zeppelin’s Stairway to Heaven at the end of the half hour show.

The exhibition for 2017 was titled, The Fantastic and Marvelous World of Bosch, Brueghel and Arcimboldo, and was a retrospective of fifteenth and sixteenth century Dutch painters. It was all the title promised, with a huge dose of surrealism, and apocalyptic enough at times—with piles of the dead and dying and mounds of skeletons—that I worried the many children around us might be traumatized by the experience. The whole situation was one of the most unusual and impressive things I’ve ever seen.

Afterward, we hopped in the white wagon and rolled over the other side of the mountains and through the vineyards of Les Baux, picturesque fields but for the dead and dry soil between the green rows—clear signs of chemical farming. Ted said there was nothing produced in the region that he’d want to import that wasn’t imported already, but it was lovely landscape nonetheless.

A little further on we came to signs for the St. Paul Asylum where Van Gogh stayed for extended periods, and where he produced some of his most famous works, including The Starry Night, known for its spiraling skies, so we pulled off and walked around the grounds. The facility was closed for the holiday weekend, but the property was enough; it was an incredible sea of tall grasses rolling in waves like ocean water under gnarled and bent olive trees that we wanted to believe were the same ones Vincent painted almost a hundred and thirty years ago.

The way the grass moved in the wind under the swirling clouds above evoked so many pieces I’ve seen, the reversal of the experience of seeing the work evoke a place. I don’t think I was alone in feeling like I had walked into a picture of history, and it all brought to mind some recent research I had come across that suggests that Van Gogh’s illness somehow let him see the spiral patterns that occur in nature, was actually able to observe the way the wind moves and light in a night sky swirls, things that are there and we may sense, but are invisible to the rest of us. As with so many other disciplines, it is these masters who are put here to show us everything the vast majority cannot access on our own.

Our plan for the next stop was to visit the nearby town of St. Remy-de-Provence, but we ran out of time; we had to get back to La Fabrique for dinner and we rushed to make it. La Fabrique, however, works on its own schedule, and by seven, dinner was nowhere in sight. I grazed in the fridge and worked out with my TRX tied to an olive tree, garnering yet more quizzical looks from those on their seventh cocktail of the day. It was Easter weekend; what was this crazy American (so different from Ted, who could easily pass for French) doing? I went to lie down and doze in my room as the sky turned pink outside my window and a horse whinnied in the field across the way.