Pruning in Les Damodes, December 2025

Here I am once again with a kind of perverse optimism at the start of a new year, even as things feel dire—especially when the feeds read like Mad Magazine comic strips playing out in real-life U.S. governance. I must be one of the most optimistic U.S. wine importers going into 2026. The truth is, the alternative to optimism is way too cumbersome, and I’m fed up with being fed up. No más, por favor. There are many New Year’s resolutions on my list. Still, the most crucial one stumbled out of my mouth while walking with my wife (now written in stone): no matter what hardship comes, thou shalt not trouble thy wife with foolish irritations, nor grant them dominion over the day (no more Chernobyl in thy head for hours—a New Testament–level expectation). And if I fall short of my own expectations, I’m going to sleep with a clear mind and a clear conscience and lean into the far end of my forties. 2026 is going to be different.

“Everything can be taken from a man but one thing: the last of the human freedoms—to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances, to choose one’s own way.”

— Viktor E. Frankl

With that in mind, we’ve got a lot to cover this month. We’re keeping the deep dives to five main headliners: the very successful 2023 Burgs from David Duband and Christophe et Fils, the Wasenhaus 2023s, and from Italy’s acetabulum to its plantar arch, Castello di Castellengo’s dazzling Alto Nebbiolos and Sergio Arcuri’s profound Ciròs.

Outside of those, we have a pile of 2024s: Manaterra’s salted-lemon sun Vermentino, Paglianetto’s Ride the Lightning Verdicchios, Manuel Moldes Albariño Afelio, the exciting old-vine bright red and gorgeous 12.5% Navarra Garnacha “Birak” from Aseginolaza y Leunda, La Battagliola and their lighter-than-ever Lambrusco, Tuo Pinot Grigio (a monster success beyond expectations), the finely tuned 2021 Quercia al Poggio’s Chianti Classico—and, Cartaux-Bougaud’s Crémant du Jura with its adorable new label.

Now let’s dig in.

Christophe et Fils

2023 Chablis 1er Crus

(Available in all U.S. from The Source)

We had a great visit with Sébastien Christophe during our end-of-the-year dash in December, where we covered ground all over Burgundy, Beaujolais, Jura and the Northern Rhône. Speaking of traveling, Séb has traveled a great distance since vinifying his first half hectare of Petit Chablis in 1999. He has methodically acquired a multitude of parcels he both owns and rents, began organic conversion in 2021 (though he’d already used only organic certified vineyard treatments long before that), and he’s found a good method of managing the new annual heat that seems to be ever-present when the vines aren’t being attacked at the other end of the spectrum by mildew. A warmer year, his 2023s follow suit with much of mainland France: bountiful, balanced, convivial and persistent. They will provide solid short to medium-term delivery, and we’ll see what happens in the long game.

Sébastien Christophe, December 2025

Cellar Quickie

All of Sébastien’s vines are located on the Serein River’s right bank (the grand cru side), and all grapes are hand-harvested, spontaneously fermented, and go through malolactic fermentation. His Petit Chablis and Chablis are aged entirely in steel, while his Vieilles Vignes and the premier crus are principally aged 80-85% in steel with 15-20% in oak barrels equally split between new, 1-, 2-, and 3-years-old, and 10% for the Vieilles Vignes. All are filtered before bottling. The style is classically spare and mineral-driven, resulting in precise and vertical Chablis closer in style to the nearby Loire Valley whites than those of the Côte d’Or.

THE WINES

Between the premier crus and the Christophe starter range sits the lonely Chablis Vieilles Vignes—too substantial to be grouped with other Chablis appellation wines and yet outside the premier cru club. Sourced from two parcels in Fontenay-près-Chablis (one above the premier cru lieu-dit Côte de Fontenay and the other southeast of the village), these vines were planted in 1959 by Sébastien’s grandfather at roughly 150 meters of altitude. They render a wine that enters rich and broad, then tightens with aeration (the opposite of many wines), shedding superficial weight and concentrating power. Minerally and deep, it often rivals one or another of Sébastien’s premier crus in any given year. Were these west- and north-facing parcels set in a more southerly exposition and outside the small valley they inhabit, they would certainly carry premier cru status. Alive with textural grit and dimension, the acidity remains fresh, the savory fruit impressions seem hardly touched by sunshine, and the wine narrows into a dense, mineral-driven core. It shows, with clarity and authority, the outer limits of what a Chablis “village” wine can achieve.

Similar to Christophe’s Petit Chablis and Chablis, it’s hard to predict which Premier Crus will show the best out of the gates; it’s anyone’s game upon arrival, no matter the pedigree of the cru. What remains somewhat consistent, at least in my experience, is the way they behave in general.

Fourchaume is the most muscular wine in the range of Sebastien’s premier cru Chablis. Deeply textured in the nose and the palate, the wine shows grit and dense, mineral impressions. This is one of the great premier crus on the right bank of the Serein River. Planted in 1981 at 120-130 meters altitude and just north of the grand cru vineyards, Fourchaume nearly picks up where they left off. It comes from the lieu-dit, Côte de Fontenay, situated on a perfect south-face, which is advantageous for achieving full ripeness in colder years.

New label design coming for the 2024 vintage

Located south of the grand cru slope and Montée de Tonnerre, Christophe’s Mont de Milieu parcel was planted between 1980 and 1990 on a south-facing, medium-steep slope at 190m on shallow marne and marl-rich topsoil. It’s the opposite of the muscular Fourchaume and closer to Montée de Tonnerre in style and location, Mont de Milieu is sleek, fluid and versatile, resting more on subtlety than force than both its compatriot premier crus in the range. It often shows a distinctly left-bank balance with its ethereal minerality and more vertical frame.

While Montée de Tonnerre takes pole position in what many Chablis followers consider to be Chablis’ super-second premier crus, it doesn’t always finish in first place chez Christophe et fils. The title of best premier cru here is up for grabs each vintage, and all have the potential to top the podium. Each taster’s preference and calibration on balance varies, and the moment the wine is tasted—influenced by the mood of the taster, the environment, what they ate or are eating, anything they tasted beforehand, the order in which the wines are tasted, the cork, the moon, the barometric pressure, etc.—will decide their frontrunner. Indeed, most compelling wines aren’t static, and neither are we. The wine we prefer today may not be what we prefer tomorrow. This makes the evaluation of wine fun and challenging, but sometimes maddeningly elusive, especially in moments when trying to recapture the experience of an extraordinary bottle and the follow-up turns out to be inexplicably off and deflating. With too many variables, a firm conclusion based on a single taste, bottle or moment in time, is shaky ground. Sébastien’s parcel, planted between 1980 and 1990 at an altitude of 200 meters is entirely located within the well-protected (from wind and hail) lieu-dit, Côte de Bréchains, within Fyé Valley. Its western aspect and deep marne topsoil (calcium-rich clay) mixed with Portlandian scree and Kimmeridgian marlstones contribute to this wine’s broad range of complexity and appealing characteristics.

David Duband

2023 Côte de Nuits & Hautes-Côtes de Nuits

(Available from The Source in select states)

Monsieur Duband

Côte d’Or 2023: What They Said

“The 2023 Burgundy vintage delivered an abundance of approachable, fruity red wines as well as lush, round whites for early drinking.”

“If one characteristic defines the 2023 vintage in Burgundy, it’s abundance. For Pinot Noir, this was a year of abundant yields; for Chardonnay, 2023 is a year of abundant flesh…”

“Best year since 2015 in the Côte de Beaune, with ripe, focused black fruit flavors, fine structure and freshness.”

“The early view that whites might stand above the reds in 2023 was justified because Chardonnay performs better than Pinot Noir at higher yields.”

“Overall, 2023 Burgundy is an engaging vintage for white wines, which are ripe, supple, juicy, and medium-full. Over the course of ten days in early September, the aromatics and fruit flavors evolved from citrus, through white peach and golden, to tropical.”

“Expect delicious and juicy white wines, without evident dilution, but probably not destined for the very long haul… By the time I finished the tasting program, I had become more enthusiastic–in some cellars, this clearly really is a great vintage.”

“The 2023 Burgundy whites are not unlike the 2022s, but with a little less acidity, depth, and structure … Alternatively, they are somewhat like 2017, with more alcohol and body but less acidity … The wines that feel sweet on the finish remind me of 2019, but with less acidity and less concentration.”

My Limited Take

2023 Burgundy surprises me. Throughout the region, from Chablis down through to Beaujolais, this bumper crop of balanced fruit delivered a much-needed cellar restock in time for the tiny quantity produced in 2024, where losses across much of Burgundy were catastrophic. For growers like David Duband, who lost around 90% of their 2024 crop, the generosity of 2023 isn’t just a gift; it stands as a bridge over the collapse of his next vintage to the seemingly strong medium-sized crop in 2025. After tasting the 2025s out of barrel in several cellars in December, I’m optimistic about them. It continues the winning streak of the ‘5s, where ‘85, ‘95, ‘05, ‘15, and now 2025 delivered some seriously good wines.

According to Burgundy journalists, Chardonnay and other white Côte d’Or varieties are the most consistent across the greater region in 2023, showing freshness, precision, and a faithful expression of terroir. After ten days in Burgundy in December, this aligns with my experience so far in the Côte d’Or and throughout many regions in France, even outside of Burgundy. The 2023 whites are easy to drink, and even if lower average acidity is a criticism, the overall balance is good. The acidity matches the elegant and subtly complex profile, and I’ve often found a recurring nuance, contrasting sweet green and very subtle gold fruit and herbal notes.

The warming trend continues to pull today’s wines further away from the past—away from that combination of natural core density, internal snap, and the measured austerity of cooler eras. Still, some producers manage remarkably well. I continue to enjoy Côte d’Or whites and Chablis from certain growers (even in warm years), but many, particularly of the former, fall short of the promise implied by their prices, while Chablis remains a bargain. Chardonnay in the greater Burgundy area remains compelling and complex, but more often now new releases feel like an aging iconic musician settled into a long Vegas residency; the taste and complexity are still there, just not the same charge.

Nowadays, when I peruse a list rich in Côte d’Or wines, there are too many average growers at exceptionally high prices. I get it, the appellations command certain prices, and no grower is going to be the one who’s not cashing in on that. But I ask myself, who are the suckers who still throw hundreds down on average wines that don’t deliver on the promise of price and pedigreed appellation? Once wine crosses a certain price threshold, ho-hum won’t pass muster. No single ounce of wine should really cost $25, so a $25 sip of a $400 bottle better be absolutely mind-blowing.

The disconnect between price and performance has widened to the point where expectation outpaces delivery, often leaving even committed Burgundy drinkers unsure of what, exactly, they’re paying for anymore. Many top-shelf Côte d’Or wines seem to be graded—and accepted as though—on a curve within the context of their season and recent vintages. They’re more skinny-fat, underdeveloped versions of the core compaction of the not-too-distant past. What once felt like wines built from the ground up with tension, depth, and a kind of internal discipline are recognizable but often underwhelm. Prices are simply too high now for most wine lovers with modest budgets, and I wonder how many of the smaller growers even justify drinking their own wines these days when they can get so much for them. (Don’t get high on your own supply!) I stopped drinking most of my cellared wines and have begun to sell them because, even if I paid twenty or thirty bucks two decades ago and they’re now worth hundreds, I still don’t like to drink beyond my daily budget. I’ve always had an overpowering bargain shopper in me, and I don’t like, as I often say, “to drink money.”

Price is one of the many reasons why I appreciate our two main Côte d’Or growers. Rodolphe Demougeot and David Duband both perform at a high level with great value compared to other top domaines. They scratch my itch without breaking the skin.

2023 was also a wonderful surprise in many of the white wine-producing appellations in northern Europe. Even the hot 2022 delivered, seemingly propped up in many regions by the reserves rebuilt through the cold and rainy previous season. I admit that I have an easier time with warmer Burgundy years with Chardonnay than Pinot Noir: the knife’s edge that Pinot Noir teeters on is often too unforgiving in overall profile, for me. If the fruit is even just a little overripe and the flowers lightly wilted, it’s so contrary to what compels me to drink Pinot Noir-based wines that it’s hard to power through a bottle. A lack of vibrant tension of fruit and the lift of flower strongly present in its youth is, to me, a misfire. Red wines from the world’s greatest terroirs often have floral elements not only present but often in the forefront when they’re young, and continue to pleasantly haunt decades after their birth. When the flower fades, my passion for the wine fades with it.

Where high yields often signal dilution, the 2023s I’ve had so far have held their shape remarkably well, showing sound concentration, brighter fruit and better fluidity at this moment than 2022, along with better integrated tannins. In some ways, the vintage for reds seem to echo 1999, another high-volume year with extremely solid quality that a few reviewers initially overlooked due to the perception that the high yield would dilute the wines too much, yet I don’t think the same mistake is being made with the critics in 2023. Grading on the curve, perhaps? Not entirely. The stuffing’s mostly there, but who really knows if the season will yield a mass of vin de garde, yet balance is known to carry wines well beyond expectation. Yields are a useful reference point, but not a predictor of quality. The conditions of the year, the reserves from the previous year (maybe 2021 didn’t only prop up 2022 but also 2023!), and the strength of each vine matter more than a tidy hectoliters-per-hectare figure. When decisions are made plant by plant, rather than by tractor passes or uniform vineyard recipes, generous crops can still produce balanced, age-worthy wines, and this is where the divide becomes clear: growers who work in their own vineyards will make those micro adjustments rather than run the same play no matter what the vines show them. David’s wines are so reliable now from one year to the next, it’s apparent that he’s adapting (even if he gives the same generic answer each season when asked about whole cluster percentage, new wood, etc.). For growers like David, that adjustment appears in subtle ways rather than dramatic stylistic swings from season to season.

2023: What Duband’s Wines Say

Across both colors, the wines show a straightforward and proportionate sense of alcohol, acidity, fruit, and tannin, all falling into place without any forced adjustments. This is not a vintage that presses its claim to greatness; it offers the early pleasure of wines already speaking in complete sentences, yet likely with enough guts to reward those in search of the complexities developed years down the road. And while many regions benefit from newfound consistency in the fully ripe flavors where they once occurred only every four years, Burgundy is facing a harrowing climate change dilemma—it’s particularly existential (at least for the new generation) in the prime historical spots. Aside from the challenge of frost and hail almost every year, the solar beatdown on what makes it to harvest day is, on average, may be off balance if one uses the past as the measure. But somehow, 2023 is a little different. (So is 2025.) Those high yields, which were often seen as harbingers of diminished quality to come, work well in warmer years to buffer concentration and alcohol with slow ripening. This is apparent in David’s 2023 range.

While the bandwidth of David’s wines is intentionally narrower than that of other growers, I love the idea of near radically different but similarly compelling wines from the same grower working the same ground each year. The intuitive part is to allow the voice of the season to shine brightly early, or remain quiet but with a smile, or even turn inward if that’s where they’re going for a period, revealing itself in its own time. A closer look at David’s gentle craftwork reveals his true artistic symbiosis with nature’s path: to do little more than place his signature where it can’t be ignored.

2023 was a hot year that followed another hot year that came after a frigid and wet year. Although it has a very different profile than 2017, a year that started with a cooler growing season, then went nuclear in the summer (the inverse of 2025), 2022 and 2023 are surprisingly resilient and fresh given the extreme heat. While 2022 theoretically had more water reserves after the 2021 rains, 2023 probably didn’t have as much. But somehow, like many red wines across continental Europe, Duband’s and Demougeot’s ‘23 reds seem finer than the 2022s: equally more open but more reddish, lifted and ethereal. The 2023s from Duband have a similar, slightly roasted bright Nebbiolo-like red and orange fruit and flower component that shows a little more like 2019 without the slightly roasted notes. 2023 was indeed hot and plentiful, but so were many years that produced fabulous wines. Duband’s range is full of generous wines with enough nuance to remind you of the breed of this region, even in the face of difficult weather for such a sensitive bunch of grapes.

Cellar Quickie

Stems are included in all Duband red wines (average: 30–40% for Hautes-Côtes and Bourgogne, 70–80% for Village/1er Cru, 80–100% for Grand Cru). Fermentation is assisted with a pied de cuve developed from the first batches of grapes harvested. Pigeage (punchdowns) is done by foot to avoid breaking stems and begins after fermentation starts, with 5 to 7 total over the full 17–18-day maceration period. Remontage (pump overs) is used only when reductive elements appear, which is more common in organic wines. After pressing, the wines settle in tanks for 2–3 weeks to allow whole-cluster ferments to clarify more fully (destemmed ferments clarify more quickly). The wines are racked for the first time before the end of the year and moved to barrel (20–25% new oak for Hautes-Côtes and Bourgogne, 25–30% for Village and Premier Cru, 30–40% for Grand Cru—all a little lower than in recent years). Since the 2022 vintage, sulfites are added for the first time only in December and January after malolactic fermentation, and a small 7 mg/L dose was added at crush. No filtration or fining.

Hautes-Côtes

David’s style of Chardonnay resonates with us. They’re clear, clean, free of technique, toying to push up reductive elements to get the wines to zoom in more on minerally impressions than fruit. They are direct and classic wines, and will resonate with historical Burgundy drinkers and even the California palate. His Chardonnay Hautes-Côtes de Nuits comes from 40-year-old vines (2024) in the Hautes-Côtes de Nuits, planted on medium-steep slopes with a southwest exposition on limestone bedrock and clay topsoil.

Surely the absolute best deal in Duband’s price-sensitive range is the Coteaux Bourguignons Rouge. It’s a total darling. So easy to drink. So pure Pinot fruit. So pure Burgundy without any pretense. After having it in the cellar this December, I went home to open the single bottle I had at my house. It was just like the tastes we shared with David at the cellar, only a full bottle to see if it veered off course, which it didn’t even after a few days of observation. Too good, in fact. The only challenge with this kind of wine for those of us who enjoy a long night of slow wine appreciation is how easily it can go down. It comes from 30-year-old vines (2024), planted to 70% Pinot Noir and 30% Gamay, on a northeast exposition on limestone bedrock and clay topsoil.

Hautes-Côtes de Nuits principal location for ‘Louis Auguste’ bottling

In 2023, the aromatic appeal of the Hautes-Côtes de Nuits ‘Louis Auguste’ is more pure and elevated earlier on than in any other year I remember. In many years past, it had to jump the hurdle of reduction, but this year, that’s nowhere to be found in the nose for more than a short moment. Perhaps this is the most upfront and elegant version of this wine I’ve had since the 2008 vintage we first imported. It comes from parcels in Chevannes, planted in 1995 on very steep slopes with south and southwest exposition, at 335–455 meters, on limestone bedrock and shallow, rocky clay topsoil.

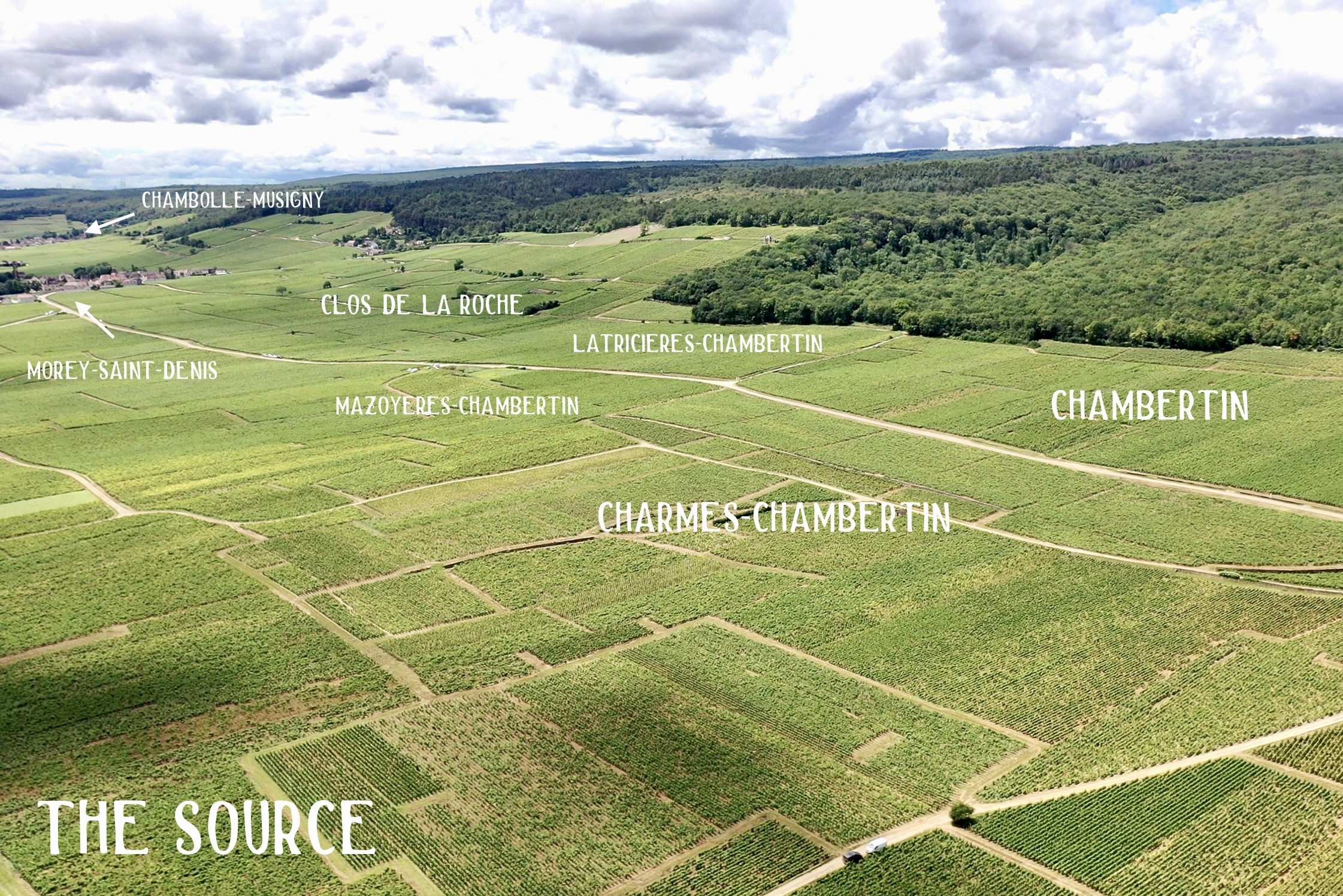

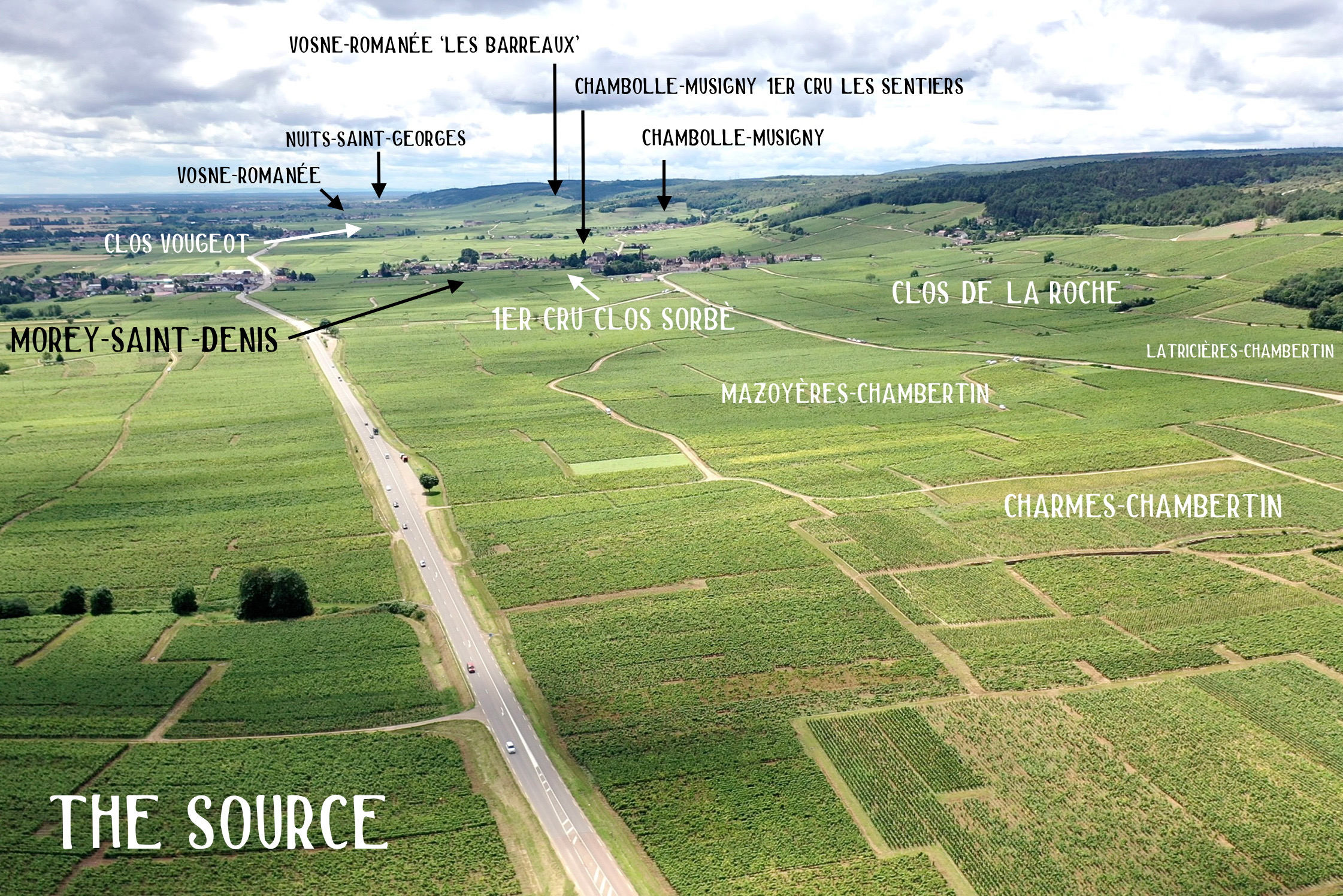

Côte de Nuits | North to South

Now we’ll take a tour of the côte, starting in the north and working our way south. The appellation classifications will vary, but it will better serve the identity of each wine and the changes in elevation and exposition along the côte rather than focusing on classification as the guide.

The wines that are often overlooked but rarely underdeliver are the Côtes de Nuits-Villages that come from Brochon; think Denis Bachelet. A substantial wine with a rare label is this Côte de Nuits-Village planted in 1995 entirely in Brochon (the sliver of land between Gevrey-Chambertin and Fixin) on gentle slopes with east and southeast expositions at 220–250 meters on limestone bedrock and shallow clay topsoil.

A commune of many faces, Duband’s Gevrey-Chambertin comes mostly from the area most known to produce elegant wines: again, Brochon—think Denis Bachelet’s and Jean-Marie Fourrier’s Vieilles Vignes wines, and this will give you an understanding of the quality of this area inside the commune. Because of the dominance of fruit from Brochon, this wine is notably more lifted and elegant than the typical Gevrey-Chambertin appellation wine. Duband’s parcels come from Les Journaux, Les Gueulepines, Les Croisettes, Pince-Vin, as well as a small dose at the southern end, Les Seuvrées (a village lieu-dit just below Mazoyères/Charmes Grand Cru and on the border of Morey-Saint-Denis) and nearby Reniard. The vines were planted in the 1970s on gentle slopes with east and southeast expositions at ~250 meters on limestone bedrock and red/brown clay topsoil.

There isn’t a more profound wine in Duband’s range than his Chambertin. Going north to south leads to his top grand cru before all other grand crus are explained. And while it seems that occasionally one grand cru in the range could squeeze in there and oust it, I’ve never had that experience in fifteen years of tasting the range at his cellar. Even within a one-ounce taste after working through the range, it always stands alone, not only in profundity but in style. His whole range is lifted, and while this is too, it’s a hammer when it strikes the palate, exploding, expanding, and resting on it like an emperor on his throne. Long known to perform its best in warmer years compared to cooler ones because of its slightly flatter surface, and the cooling Combe de Grisard, Chambertin’s Siamese twin to the north and outside of the combe, Clos de Bèze, can sometimes perform a little better in the cooler ones. Chambertin may have the edge between the two with today’s climate change. David has two parcels of about 60 years old that add up to 0.22 hectares: one up high at around 300-310 meters, and another one that runs from the top of the slope to the bottom, dead center at 280-300 meters, both on limestone bedrock and shallow (20–25 cm) red and white clay topsoil. Yes, it’s pricey, but unlike many grand cru experiences, this won’t leave you wondering why it’s considered to be one of the greatest vineyards in the world.

How to follow Chambertin … Perhaps the wine to do it inside of David’s range is the Latricières-Chambertin, Chambertin’s southern bookend, his parcel located approximately thirty vine rows south of the Chambertin border. This has long been one of David’s rarest and hardest-to-get grand crus. It’s more charming with more upfront fruit and elegance than Chambertin, but not as galactic in breadth. We got our first minuscule allocation around the 2016 vintage and would take every bottle offered. It’s the wine in the range I know the least (due to price and scarcity), but each year I’ve had a taste at the cellar just before Chambertin finishes the flight. It’s sometimes easy to forget once Chambertin has colonized every bit of surface area in the glass, wiping away the memory of almost all that came before it. But if it were the last wine tasted, it could still take the throne and resonate even more. It comes from vines that were 65 years old as of 2023, on a gentle slope just inside the Combe Grisard with an east exposition at 280–300 meters on limestone bedrock and shallow (10–20 cm), rocky brown clay topsoil.

While perhaps more compact and reserved than other charmers from this grand cru, the old vines in David’s Charmes-Chambertin, planted in the 1920s at 270-280 meters on shallow (10-20 cm) rocky brown and red clay topsoil, give the wine tremendous depth, and historically it has been a slow reveal. That dynamic is beginning to shift. A small but meaningful replanting in 2016 has introduced younger vines into the blend, bringing a new immediacy and aromatic lift that wasn’t always present in recent vintages. Even so, with an average vine age still quite old, this remains one of the most physically imposing wines in the range—built for distance, not for speed. The parcels lie in Mazoyères-Chambertin, a climat labeled as Charmes-Chambertin, though the distinction matters. (Wines made from the Charmes-Chambertin climat cannot be called Mazoyères.) The imprint on wines from Mazoyères differs from most Charmes: cooler air, deeper and rockier soils, and a longer line of tension, thanks to its position in the path of the Combe Grisard, which formed the terrain in the past and now dictates to some degree the air currents and temperature. This wine has behemoth tendencies, often backward in its youth, but the sun also rises here without obstruction now. With it comes a renewed sense of charm, perhaps at only a modest cost to extreme long-term aging; it’s a wine that carries its strength calmly and without bravado.

Few other wines than Clos de la Roche represent my strongest emotional center in the Côte d’Or. Perhaps others follow—Clos Saint-Jacques, Ruchottes-Chambertin, Musigny. One could posit that our entire portfolio’s red wine style is based on the general character of the wines from these specific vineyards: high tension, expansive, a slight tilt toward bone rather than flesh, a solid opening, a slow but intense burn, and always a forcefully dynamic second half. In my earlier years, I could afford to splurge on a bottle here and there—an expense shared with friends, of course. In fact, a bottle of 1985 Dujac represented a turning point in my wine life—a decisive pivot toward Burgundy. Like his Echezeaux parcel, David has great fortune with the position of his Clos de la Roche. It comes from the center of the cru, in the original Clos de la Roche lieu-dit, before the later expansions. The vines, planted in 1960, grow on a gentle to medium slope with an east exposition at 285–295 meters, rooted in hard limestone bedrock with shallow (10–20 cm), rocky brown clay topsoil. Like his 1er Cru Clos Sorbè, the equilibrium of this wine—on a slightly bonier frame for a grand cru, reminiscent of Ruchottes-Chambertin—is of the highest order, where restraint, depth, and authority endure. David’s rendition of Clos de la Roche springs quickly from the glass, but it asks restraint in return; only with patience does its full measure reveal itself. Like most great wines, this should be shared between two people, three at most. Any more than that, and the full wingspan and depth of this beauty are cut too short.

Perhaps the wines that carry the deepest emotional value with me are those from his Morey-Saint-Denis holdings. All are wonderful, charming, beautifully choreographed, and capture the “completeness” of this fabulously tiny commune stacked with as much talent in the cellar as any other on the côte. As I write about this collection of vineyards from north to south, I know well where my preferences unintentionally land. Like his Nuits-Saint-Georges village wine, this wine is often overlooked but delivers on all fronts. It’s hard to pick a favorite among his village appellation wines because all deliver beyond at least what’s expected, and three rise well above the expectation. While the Gevrey-Chambertin’s defining characteristic is that it primarily comes from the area that produces the most elegant wines in the commune, perhaps it’s the solid patchwork of many different parcels from different spots in the commune that make this MSD so well rounded: Les Porroux (bordering Chambolle-Musigny below 1er Cru La Bussières; planted in the 1980s), Clos des Ormes (bordering the 1er Cru of the same name; planted 1970–1980), Aux Cheseaux (planted 2011), Les Cognées (planted in the 1950s), and Les Brâs (east of RN74), on gentle slopes with mostly east expositions at 220–230 meters on limestone bedrock and clay topsoil.

There has only been one other premier cru for me that rivals the Morey-Saint-Denis 1er Cru Clos Sorbè within David’s range of premier crus, and, sadly, that’s no longer part of the range: Les Gruenchers. For this taster, this wine is the full embodiment of Duband’s work from across the entire côte, taking a chapter from all classifications, from Coteaux Bourguignons to Clos de la Roche and Chambertin. Nothing here strikes in an extreme tone of high or low; it’s a wine of resolute balance, containment, intellectual currency and class. It comes from vines planted between the 1950s and 1990s on a gentle slope with an east exposition at 260 meters on limestone bedrock and shallow red/orange clay and rocky topsoil. In my mind, this, along with Clos de la Roche, is the heart of David’s production.

Similar to his village appellation, the Morey-Saint-Denis 1er Cru Les Broc comes from a collection of micro-parcel top vineyards, only this time all premier crus, so it’s a serious upping of the ante. While Clos Sorbè is more individual due to its parcel singularity, the mix of superstar premier crus that go into Les BROC sit around it and below the grand cru slope; they are Blanchards, Rouchots, Ormes, and Chezeaux, and they forge a robust wine with a little more stuffing and breadth, with the average vine age of 55 years. Another grower in the appellation, Virgile Lignier put it succinctly: the slopes here are gentle but deceiving in position. In the middle of this row of premier crus between the village and Gevrey-Chambertin, a reverse fault uplifted some bedrock below, creating a shallower topsoil bed than what one would expect. This shallower soil on gentle, east-southeast-facing slopes reads, in body, a little finer like a higher-altitude premier cru than one at this altitude, but with a slightly riper and fuller fruit profile. So many special wines come from this premier cru section of this commune, and this, even if it’s a blend of four, isn’t one to miss—a unique singularity of this strip of the Côte d’Or comes through.

David’s Bourgogne Rouge has always been a reliable profile that, like the Coteaux Bourguignon, delivers on immediate appeal and doesn’t let up for days. It mostly comes from vines in Morey-Saint-Denis and Chambolle-Musigny, balanced with tension brought from a touch of his Hautes-Côtes de Nuits parcel. The vines were planted between the 1960s and 1990s on gentle to steep slopes with east, south, and west expositions at an altitude of 250–450 meters on limestone bedrock and clay topsoil.

Like David’s Vosne-Romanée that delivers on all levels expected from this “pearl of the côte,” his Chambolle-Musigny appellation wine delivers on the promise known for finesse and restrained power. It’s primarily sourced from Les Chardannes and Les Herbues (below a series of top premier crus and beneath Bonnes Mares) from vines planted in the 1970s on gentle slopes with a southeast exposition at 250 meters on limestone bedrock and clay topsoil.

Located on the north border of the appellation, next to Morey-Saint-Denis 1er Cru Les Ruchots, and just below Bonnes Mares and above “Les Bussières,” the Chambolle-Musigny 1er Cru Les Sentiers is a stouter wine than others inside this commune, further from Morey-Saint-Denis; this has to be taken into account that David’s wines are indeed always on the more elegant side despite the appellation. It comes from vines planted in the 1960s–1970s on a gentle slope with a southeast exposition at 250 meters on limestone bedrock and heavy red clay topsoil.

On April 1st, 2016, I accompanied Raj and Jordan during their vineyard tour with David for their book “Sommelier’s Atlas of Taste.” It was drizzling and freezing, and David brought us down into the muddy and flat Clos Vougeot where Raj and Jordan almost got their car stuck. I’ll never forget sitting with David in his 4X4, giggling as they slid and spun the wheels of their ill-equipped rental like they were on ice. That’s David’s Clos Vougeot: a 60-year-old plot in the center, relatively flat, 245 meters altitude, and deep brown clay topsoil. It works well in hot years, but in rainy years, it’s not ideal. With a slightly darker robe of red compared to much of the range, this powerful wine still charms with its typically smooth, velvety texture anchored in grand cru poise.

In Burgundy, it’s all location, location, location, then craft. In expansive grand crus like Echezeaux, location is paramount to understanding the potential quality and how the wine may present itself independent of the grower’s hand. David is a lucky one; much of this grand cru is greatly influenced by the Combe d’Orveaux on the north side and La Combe de Concoeur on the south side. His parcel sits right between these two combes but high enough up on the hill to place it in a more classical strata that many of the great grand crus have. It’s the lieu-dit Les Rouges du Bas, higher on the slope and from vines planted in the 1930s at 280–300 meters (the upper end of the sweet spot; e.g. La Tache runs about 250-290m; Musigny 280-300m; Clos de Tart 270-300m; Clos de la Roche 270-310) on limestone bedrock and shallow, rocky red clay topsoil. I’ve always found this to be one of his most underrated, over-deliverers one could buy in the grand cru world: 100-year-old vines, prime position away from the combes, same altitude as some of the greats, and in Vosne-Romanée? That should pique interest.

With the first sip of David’s Vosne-Romanée, one can only throw up their hands and say, “Well, that’s Vosne-Romanée for ya …” followed by a battle for restraint from pounding this charming, even voluptuous—by Duband standards—Vosne. It comes from 90% Les Barreaux, planted at an altitude of 300-340 in the 1950s on a medium-steep slope next to/north of Les Petits Monts, above Richebourg and Cros Parantoux (not a shabby hood) at 300–340 meters, tipping just inside the combe. The remaining 10% comes from Aux Ormes, planted in 1990 on a gentle slope east of the village center at 235 meters. While that 10% of Aux Ormes brings this Romanée rocket ship a little closer to earth, it’s hard to compete with the pedigree of this fabulous “village” wine, especially in the face of climate change. With vines running south to north instead of the typical west to east, the upper position of Les Barreaux tips to the north with an eastern tilt into the windy combe, facing off with Beaux Monts. This should offer more relief from today’s blistering sun compared to many other parcels in the commune. What was once a potential liability is now an asset.

It’s hard for any appellation wine to follow a Vosne-Romanée. And this is what drives growers like Duband to vigilantly pursue the key to unlock Nuits-Saint-Georges and its long-standing typecasting as a hard Burgundy with too much austere texture. A continuation of Vosne-Romanée to the south, the north end of Nuits-Saint-Georges naturally shares kinship with the wines made next door. But probably like many Burgundy pilgrims, I’ve long blistered past both hills of Nuits-Saint-Georges on my way to somewhere else on the côte—in the car and on wine lists. I can’t do that anymore. NSG has begun to heat up and shine for me. Perhaps it’s climate change. Maybe there’s been a commune-wide stylistic makeover? Or I might simply love minerally wines (obviously). Few red wine appellations express mineral and metal textures as clearly as Nuits-Saint-Georges, and now that their tableside manners have improved, they’re far more accessible. Now, if you blend roughly 20% Les Plateaux (planted in the 1950s) from the north end of the mineral and metal-heavy south hill with the Vosne side’s natural charm via 80% La Charmotte (planted 1960–2000) and Aux Saints-Juliens (planted in the 1950s) on the north hill, just downhill from the premier cru Aux Thorey, you may begin to understand Duband’s Nuits-Saint-Georges. Anyone who gives it a fair shake quickly realizes that he has, in fact, unlocked this appellation while not overplaying it. More soprano than baritone, more starlet than stalwart, it’s not a supporting role but a quiet lead inside a strong cast. I’ve tasted in David’s cellar every year for the last fifteen years, and every time I conclude that people should know this wine: a fresh and cool mineral-armored but refined texture and the right amount of fruit to charm without betraying its roots. It’s not what you might expect, unless you’ve had it before: a triumphant parry to any preconceived notion of what it “should be,” because it’s far better.

Toward the tail end of Nuits-Saint-Georges’ north hill, Duband’s Nuits-Saint-Georges 1er Cru Aux Thorey comes from vines planted between 1950 and 1980 on a gentle, medium-steep slope with a southeast exposition on shallow, rocky, orange clay topsoil. This is a transition wine with similar but more restrained generosity of the Vosne-Romanée side, with a textural profile that only whispers its connection to the south hill—think a slightly more Ironman build than NFL running back. Aux Thorey has always been solid from David, and in way, a Côte de Nuits wine that uniquely carries orange fruit and flower notes, refined minerally textures, rusty iron, and a refinement that one may see as a common thread to a young but already secondary orange-infused Giacosa Barbaresco or Le Ragnaie Brunello while still obviously Côte d’Or Burgundy. Of all in the range, Aux Thorey and its brothers on the NSG south hill, Les Pruliers and Les Procès, not only thrive with food, they’re made for it.

The neighboring plots, Nuits-Saint-Georges 1er Cru Les Pruliers and 1er Cru Les Procès are on the north end of the premier cru line on the south hill—the hill best known for its ferrous-inflicted wines. In a line of three, one could say that well-dressed beast of the range, Les Pruliers, is a firstborn filled with expectations and strength, Aux Thorey the middle, the quieter intellectual, the listener, finer lines, and the third, Les Procès, a little bit of both but naturally closer to Les Pruliers. Pruliers and Procès from vines with an average age of about 60 years on a gentle slope with a southeast exposition. The difference, as explained by David, is that Les Pruliers receives a little more sun than its brother, who’s tilted slightly toward the north. Les Pruliers also has deeper topsoil, making Les Procès a little more minerally with a touch less muscle—indeed, right in between these NSG premier crus.

Sergio Arcuri

Riserva Cirò | 2021 Aris & 2021 Più Vite

(Available from The Source in select states)

Sergio Arcuri is a madman, in all the right ways. Aside from being one of the highest-maintenance growers we work with (constant flurries of texts, photos, gifs, ideas, needs), he’s also one of the most inspiring. He’s the man leading the charge of Ciró, one of the most compelling and least understood truly great appellations in Italy. Under his hand, the reds from Gaglioppo are marvelous—pure, clean, cultural, historical, singular.

We just received two of his newest iterations of extended concrete-aged Ciró Riserva wines, but before we get to those, a little refresher, or, for those who aren’t yet familiar with this secret stash of southern Italian dynamite, an introduction to Cirò. For this taster, lover-of-wine, obsesser, Gaglioppo is one of Italy’s finest varieties and belongs on the list of the country’s top red grapes.

Cirò Refresher

Cirò is one of Italy’s oldest wine regions, once known as Enotria, “land of wine,” and viticulture has existed in Calabria for thousands of years. Although the Cirò DOC was born in 1969—one of the first in Italy alongside Barolo and Brunello—its deeper history stretches back to the Romans, when wines traveled from Cirò to Rome two thousand years ago. Despite this lineage, Cirò fell into decline after the 1970s as many producers chose quantity over quality, nearly destroying the name. Over the last decade, a group now known as the Cirò Revolution began restoring vigor and interest by bottling true Cirò made entirely from Gaglioppo.

Gaglioppo is pale in color, high in natural acidity, and capable of producing big tannins if not managed well, with a durability that can match history’s great wines. Sergio Arcuri considers it one of Italy’s longest-standing, unshakable pillars of red wine, uniquely suited to Cirò’s dry and hot Ionian seaside conditions. Its thin skins make it extremely susceptible to mildew, which is why it has thrived for millennia only in this arid coastal corridor. Thanks to Sirocco winds from the Sahara, Tramontane winds from the north, and the Sila Massif to the west, there are years when no treatments are needed at all.

Cirò’s vineyards grow on geological depositions from the Miocene, Pliocene, and Quaternary, with soils composed primarily of calcareous clay. According to Sergio, clay—not slope or visual drama—is the principal ingredient for high-quality Gaglioppo, especially in the flatter areas near the sea, such as the Lipuda River delta (see pedological map). Most of Arcuri’s six hectares lie beside the sea, with the highest reaching just 70 meters in altitude.

The Arcuri family has made wine in Cirò since 1880. Sergio was born in Cirò Marina in 1971 and grew up making traditional Cirò with his father, never missing a harvest even while working elsewhere. He bottled his first vintage in 2009, commercialized his first rosato in 2010 and rosso in 2011, and today leads the family’s vineyards with his brother and nephew.

The Wines

The first and more upfront of the two Gaglioppo reds, the Cirò Rosso Riserva ‘Aris’ is picked toward the end of September (usually a week or more before “Più Vite,”) and is produced with 40% of its grapes originating from the Piane di Franze vineyard replanted forty years ago at an altitude of 70m and in full view of the sea. Its soil is red clay, red sand, and silt, and the remaining 60% of grapes come from the Piciara vineyard with vines planted seventy years ago on calcareous clay just next to the sea at a few meters in altitude. In the cellar, the wine is fermented naturally under a submerged cap with no movements/extractions of the must. After three to four days of fermentation, the wine is drawn from the tank, and the grapes are very lightly pressed (with the stronger press juice/wine sold to bulk wine production). Aris is aged in concrete for twenty months before bottling, with its first sulfite addition made after malolactic fermentation and then again before bottling. Aris is then aged in bottle for one year before going to market. The total SO2 depends on the vintage and ranges between 30-50 mg/L (ppm).

On January 4th of this month, I opened a well-rested bottle of 2021 Cirò Riserva ‘Aris’ waiting in my cellar since July. These wines, destined for California, arrived at our warehouse mid-December, and I hope they will show as brilliantly as the bottle I opened on the last day of the winter holiday stretch. It was stunning. And outside of the company of Più Vite, it could alone carry the burden of proof for Cirò’s deserving place in the conversation of the greats. No doppelganger of Barolo here, only pure southern Italian nuances: a deeper and sweeter version of anise and tar with bright sunshine red and dark fruits, beautiful sappy red fruit heavy on cherry nuances with sun-dried red rose, dried sweet orange peel, persimmon, and guava, and loads of iron-led metal/mineral notes—much more relatable to its further south vinous brothers and sisters, Nerello Mascalese and Frappato, rather than Sangiovese and Aglianico—to all of which Gaglioppo is genetically related. It’s the fuller and punchier of the two Cirò wines and an easier mouthful for newcomers to this historic region. This 2021 is a stunner, and I want (need!) a lot more of it.

The Cirò Riserva ‘Più Vite’ is produced only in select years from the Piciara vineyard on the sea, on land with clayey soil and 70-year-old vines. Usually picked in the first week of October, it spends 9-15 days of maceration and spontaneous fermentation under a fully submerged cap with no movements of the must. Like Aris, the wine is then lightly pressed, with the harder-pressed wine sold in bulk. As one would expect, this wine has a greater phenolic and tannin ripeness, which leads Sergio to age it for four years in concrete with no movements until bottling. The first sulfite addition is made after malolactic fermentation, with an additional one during the first year of aging (if warranted), and rarely more for the following 2.5 years before bottling. The total SO2 depends on the vintage and ranges between 30-50 mg/L (ppm).

The 2019 Più Vite’s four years in concrete softens the fruit compared to Aris’ shorter affinamento. It’s rustic and savory, and young versions often lead with earthy notes of kiln-dried red clay, fall leaves on wet soil, chestnut, saffron, leather, iron, animal, braised meat, and rose water. Fruit is present but delicate, and it emits notes of ripe persimmon, shriveled golden apple, dried orange peel, and wild cherry. More tannic than Aris, the 2019 Più Vite balances firmness and delicacy but with a more solar-fruited profile than the epic 2016. Hours after opening (even the next day), it rises and can be deceptive, indeed sometimes a doppelganger of a top-tier, traditionally made Barolo—tar, plush red rose, sun-touched cherry, and anise. It’s versatile and may be best served with a small group in an intimate setting with both heart-warming food (ossobuco, cassoulet, ratatouille) and finely crafted, Michelin-style cuisine. Epic as usual. Più Vite is one of my soul wines. Never to be missed, but never enough made.

Castello di Castellengo

2023 Rosso Della Motta & 2019 Il Centovigne

(Available in all U.S. from The Source)

Italy has been a slow burn for us since we started to import them directly for ourselves in 2018. Before that, we worked in California with several different Italian importers, so we had an idea what we were in for when we began to blaze our own trail. What’s happened over these long seven years has generated a strong lineup of relatively unknown growers before our work with them that I’m extremely proud to represent. Castello di Castellengo is yet another one that makes me beam when I think about them, and each night when one of their top wines is opened, it’s very similar to when I open a Ciró wine from Sergio Arcuri, it marks a special moment for me. These special wines simply overdeliver on expectations for both appellation and price. And, like our refresher with Arcuri and Ciró, let’s do the same here.

Refresher

Located east of the once wealthy Alto Piemonte town of Biella, and south of the prestigious Lessona appellation–whose Nebbiolo wines were once considered Italy’s finest–a unique hill stands above the eastern plain below, spared from the full erosion caused by Alpine runoff and glacial movements. This special terroir of Castello di Castellengo, featuring volcanic marine sands similar to those in Lessona and the eastern side of the Bramaterra appellation, is home to the organically farmed Centovigne Nebbiolo and Erbaluce vineyards, owned by Magda and Alessandro Ciccioni. Raised on the grounds outside their 18th-century castle, Castello di Castellengo, Magda (who is both the mind and hands behind the delicate yet flavorful wines) matures their organically farmed wines in concrete tanks and large oak barrels, blending tradition with modern sensibility.

It’s only a matter of time before the generic D.O.C. appellations of Coste Della Sesia (established in 1996) and Colline Novaresi (in 1994) need to be updated. Their D.O.C.s were established when almost nothing so serious was happening in Alto Piemonte to grab the attention of journalists and buyers. Today, several hectares (give or take 100) planted can only be classified as Coste Della Sesia D.O.C., but where it starts to get hairy is when grapes grown in other D.O.C.s that don’t adhere to the D.O.C./D.O.C.G. regulations can also be labeled Coste Della Sesia D.O.C. or Colline Novaresi D.O.C.

Viewing this appellation through terroir lenses such as geology and climate, which, of course, both affect the choice of what varieties are optimal to plant, makes them especially hard to generalize, except that they’re far too general. There’s too much quality wine made on very different terroirs all over these widespread appellations, and while some are average sites, others are spectacular and picturesque. However, dizzying eye-candy vineyards don’t immediately guarantee the highest quality, and it’s often those that are unassuming and even boring to look at that can deliver a spiritual awakening in vinous form. Take many top vineyards of the Côte d’Or, like Chambertin and its satellite Grand Crus, or the unassuming vineyards of Brézé that electrified the wine world only just a little over ten years ago.

The Wines

Before we get to the main event at Castello di Castellengo, we have to acknowledge the arrival of the 2023 Coste Della Sesia Nebbiolo ‘Rosso della Motta.’ This wine has a shocking price, in the best possible way, inexpensive, but it’s also very serious. It’s now labeled for what it is: pure Nebbiolo! What it’s best at is how much joy it unfurls compared to so many other Alto Piemontese reds that have forgotten wine is also to be enjoyed; to be fruity and merry. It’s made entirely from Nebbiolo grapes harvested from 70 to 80-year-old vines planted between 300 and 350 meters on the rolling hills of marine sand and clay. To maintain the fruit profile upfront during its two-week natural fermentation in steel, Magda keeps the temperatures maxed out at 22° C. It’s then aged on lees for 24 to 30 months in concrete without racking before a light filtration at bottling. With only 40 mg/L of total sulfur, added only at bottling, its years of refinement under the natural bacteria, yeast and microorganisms that survived and even grew during fermentation make this a truly authentic wine, at a great price. This is truly one of Italy’s best serious red wines for the price—maybe even the best for those in search of classical Nebbiolo with purity, restraint, and generosity.

The main event today with Castellengo: 2019 Coste della Sesia Nebbiolo ‘Il Centovigne.’ (Of course, the usual main event is Castellengo, but the 2017 will come later this winter!) When I first came into contact with the pure Nebbiolo labeled as Il Centovigne, it was sandwiched between Rosso della Motta (RdM) and their flagship wine, a wine that I truly adore and admire, Castellengo. Like many wines in the middle (average and even sometimes great), it was easy to overlook it, especially considering the first vintage I tasted, 2017, which was less precise and with a small but surprising dollop of newer wood that made it stand further out from the others that don’t even have a splinter. And then along came the 2019.

At first taste, similar to the 2017, it started as lost in the middle and even short by comparison to the RdM, and seemingly no match for the 2017 Castellengo that shot out in a brilliant explosion straight away next to it. The nose was indeed immediately finer that RdM, but it seemed stunted by comparison to Castellengo. But no longer than the time it took to record that sensation in my tasting diary and sniff again, like wildfire, the 2019 roared uphill and began to expand in the glass. On the second pour, the nose was quiet but only for a moment, and then the floral spice and sappy red fruit began to sing. Slowly it built and built, wearing away any will to resist. It started to march with great lift, regal aromatics and fine palate textures. A truly great wine in itself, just like my first encounter with this grower a few years ago, I was left with no choice but to import this wine and introduce it to our US market. Magda continues to find such charm in her Alto Piemonte Nebbiolo wines without overpowering technique and too much of an ode to the old-school style of half-smiles and furrowed brows, and little early joy allowed in their youth. Like the Rosso della Motta, Il Centovigne will surely be yet another one of the greatest value “great wines” of Italy. Another complete win from top to bottom for Magda and her reds.

Wasenhaus

2023 Vintage

(Available from The Source in select states)

Refresher

Christoph Wolber (on the right) and Alexander (Alex) Götze met in Burgundy while getting their enology education at the local school in Beaune. At the same time, they both worked full time jobs between some of Burgundy’s top biodynamic estates: Alex has spent nearly a decade between Pierre Morey (where we first met) and De Montille, where he is currently the chef de culture (the vineyard manager), and Christoph had some years at Leflaive, Bernhard van Berg, Domaine de la Vougeraie and Comte Armand. Shortly after they became roommates, they hatched a plan to return to Germany and start a new project in Baden, a wine region on the east side of the Rhine Graben, across from and within sight of the Alsatian wine region, all in a valley that separates Germany’s Black Forest from France’s Vosges mountains.

Burgundian monks were the first to bring the grapevines to the area, but they’ve adapted to their climate and soil types, which make them quite different from those in Burgundy, despite how surprisingly similar the Wasenhaus wines are to some from the Côte d’Or. However, one challenge to the grape selection in this highly industrialized area is that many of the ancient clones were replaced in the 1960s and 70s by easy-to-manage clonal selections that produce good yields and are more easily worked by machines. One of the tasks (and adventures) of Wasenhaus is to (re)discover vineyards within Baden with good clonal material and recoup a resemblance to the historic voice of Pinot Noir in Baden.

While Alsace has a myriad of small geological units, Baden has tremendous diversity on a much larger scale; it has granite, volcanic, limestone and every other rock and soil in between. One unique and strongly defining geological feature in Baden that affects the shape and characteristics of their wines is the amount of löess topsoil that covers many of the hillsides with the western exposure, and more so than those facing south or east. Löess is a fine-grained and mineral-rich sandy soil (often rich in calcium and alkaline in pH levels) derived in this case mostly from rock ground down by glaciers. This fine silt-like soil is then carried far away and deposited by the wind, where it has created a surprisingly structured soil; this is due to a crystalline structure that allows it to lock into place with other loess crystalline particles. Löess soils seem to round out the edges of a wine and bring a sort of soft richness to its body.

The weather in Baden is closely related to its French wine-producing neighbor to the west, Alsace, and is Germany’s warmest wine-producing region. During the winter and spring, there is a plentiful supply of precipitation. But the weather takes a significant turn during the summer and fall, and vineyards with some distance from the Black Forest become some of the driest zones in all of Germany.

2023 According to Alex Götze

The 2023 season at Wasenhaus unfolded under the long shadow of 2022, a year that remains the driest vintage we have ever experienced, defined by the least amount of rainfall on record. That drought did not end with the harvest. Winter 2022/23 followed in the same register as one of the driest winters we have ever seen, with almost no rain and no meaningful snowfall. Spring arrived equally dry, and there was real fear in those early months that the disaster of 2022 would simply repeat itself, or worse: if no rain came, the season would be even drier than before. Then May shifted the narrative. A drizzle began, gradually at first, then with enough consistency that, while never generous, rainfall continued through the growing season. It was hot, and the water was quickly consumed, offering little lasting recharge to the soil, but it proved just sufficient to keep the vines and trees green, and the landscape alive. There was no visible hydric stress during growth, no obvious shutdown in the vines.

Harvest, however, arrived with quite a bit of rain at precisely the wrong time and didn’t truly stop again until the end of 2024, or even the beginning of 2025. Despite this, fermentation told a different, deeper story. The wines still had drought characteristics: very slow fermentations, low nitrogen in both white and red musts, and constant vigilance to keep volatile acidity low and sugars moving. These are clear markers of drought vintages. Still, 2023 wasn’t rife with the pain or disaster of 2022, when nearly a thousand liters had to be distilled due to volatility, and some wines were only able to finish fermenting the following September. In 2023, everything eventually went through fermentation without problems—it simply took time. Interestingly, after harvest, a hole was dug in the vineyard following what appeared to be significant rainfall. The first five centimeters of soil were wet; beneath that, it was desert—super dry, untouched by moisture. The deeper soils had received none of the rain because it couldn’t penetrate through the grass.

What moisture existed was enough only for the superficial roots, sustained by repeated but shallow rainfall. The wines themselves reflect this tension: it’s a fruity year, bright and expressive. The whites were initially very tight and closed, especially around bottling, but they have opened over the summer and continue to shine, fresh and luminous with good tension. Across the board, 2023 finds a strong balance between quantity and ripeness. In the reds, some parcels had to be picked urgently because of rain pressure and the persistent threat of sour rot from Drosophila suzukii, a familiar battle, while other parcels reached fantastic ripeness. The result is a vintage that’s fresh, bright, and fruit-driven, yet substantial, with fine, well-shaped tannin structures in the reds and freshness and tension in the whites. Not bad at all—especially given where it began.

Whites

All white wine bunches are whole bunch pressed with a screw press for the textural effect without the need for skin contact, which brings a lot of solids. The grape must is settled overnight and barreled down with finer gross lees. The gross lees make the wines quite reductive during natural fermentation in old, 228 to 600-liter barrels, which helps to protect the wines and keeps sulfites to a minimum. They spend 12 months in barrels, then are racked into stainless steel tanks where they receive their first sulfite addition. The gross lees are also racked into the tank, where everything ages six months to settle. Before bottling, they’re racked clean from the lees, and the final sulfite addition is made.

The Chardonnay comes from a collection of vineyards from different areas between 250-300m on flat to medium step-slopes with many varying aspects. The soil is predominantly calcareous loess.

The Chardonnay “Filzen” comes from a single parcel of vines planted in 2000, 2004 and 2006, facing west on a steep slope at 300-350m. The soil is limestone and clay. From 2021 on, we have two more plots for the Filzen, with the same exposition and soil.

The Weissburgunder “Bellen” comes from Pinot Blanc massale selections planted in the 1960s on a steep slope facing west at 300m on limestone, clay and sand.

The Weissburguner “Möhlin” comes from Pinot Blanc vines planted in the 1950s on a very steep slope facing south-southeast at 350m on limestone and clay.

The Weissburgunder comes from a collection of vineyards in different areas between 250-300m on flat to medium-steep slopes with many varying aspects. The soil is predominantly calcareous loess.

Möhlin to the far left a little downslope

Reds

They are soft on extraction with very few punch downs during fermentation, only the occasional movement of the cap, mostly by hand, to ensure a healthy beginning. Sulfur is used judiciously (no more than 30-50 parts per million in total) and not applied until after malolactic fermentation. Their theory on the timing of the first sulfur addition is that the tannins would be more smoothly integrated than with additions beforehand, especially when there are whole-cluster fermentations involved. (When it’s added during the vinification period—including primary and malolactic fermentation—the wine has more time to clearly define itself; while those that have earlier additions before fermentation potentially maintain harder tannins that could take much longer to evolve in the bottle, it leaves some of the best potential moments of the wine’s life subordinate to a potentially overbearing tannic structure.) The wines are all aged in oak barrels, but it’s too early to say what their practice will be from one vintage to the next concerning the amount of new oak—they are still discovering what works.

Bellen

The Spätburgunder “Grand Ordinaire” comes from parcels planted between 1989 and 2010 at 200-300m on gentle slopes facing all directions. The bedrock and topsoil consist of limestone, loess and sand.

The Spätburgunder comes from parcels planted between 1989 and 2019 at 200-300m on gentle slopes facing all directions. The bedrock and topsoil consist of limestone, loess and sand.

The Spätburgunder “Kalk” comes from multiple plots of 40-year-old parcels (2024) at 200-300m on gentle slopes facing west-northwest. The bedrock and topsoil consist of limestone, loess and sand.

The Spätburgunder “Vulkan” (volcano in German) comes from Pinot Noir vines with an average age of 20 years (2023) planted on medium-sloping hills between 250-350m facing south on shallow black volcanic soils.

The Spätburgunder “Kanzel” comes from half 40-year-old German vines and half French Pinot Noir massale selections planted in 1999 on a very steep slope facing south-southeast at 350m on limestone and clay.

The Spätburgunder “Bellen” comes from German and French Pinot Noir clones planted in 1990 and 2000 on a steep slope that faces west at 300-350m on limestone, clay, and sand.

The Spätburgunder “Möhlin” comes from mostly German Pinot Noir clones and some massale selections planted in the 1970s and 2010s on a very steep slope facing south-southeast at 300-380 m on limestone and clay.