The French leg of my December trip with Remy would start with cassoulet, and it would end with cassoulet. At Sonya’s Provençal farmhouse, Mas la Fabrique, where I have for decades taken refuge during my European gallivants, I began writing this newsletter mid-February as she and I started our three-day cassoulet marathon. Sonya specializes in rustic French classics, sometimes with a Turkish twist—her family moved from Istanbul to Lyon when she was two, and her mother was dangerously good in the kitchen.

She and I struck a deal in December at the end of my two-week French tour with Remy as I pulled a well-seasoned traditional clay cassoulet pot from my car. Remy and I were about to boomerang through northwest Italy and I needed room to bring back wine. “It’s beautiful,” she said. “Leave it. But come back soon and we’ll use it to make the real cassoulet.” I’d planned to return soon anyway, but this would quicken the process.

I’ve dreamed of making cassoulet. That’s to say, I do make it regularly, and I’ve had actual dreams about making it—or something like it. I adore anything with white beans—stews, soups, ragouts, salads. Duck products? Addictive. Foie gras, rillette, dry salted and roasted whole duck, pan-fried breast with its epic fatty, salty crispy skin contrasting with the cool, sushi-like texture and gamey but clean flavor of the meat; the rich skin a fair trade-off for another five minutes of running.

Confit? Soul food. I enter meditation mode with salted and seasoned duck legs and wings in front of me ready to undergo the confit process. The salty, fatty, collagen-infused air harmonized with thyme and garlic energizes me. Yet, I struggle with most French versions. Often salted to the marrow, like the chef expects to be six months under siege (as one story goes), they’re often dry and fibrous, like overcooked corned beef, or a rushed Portuguese bacalhão. I need to secure a large carafe d’eau in advance.

Not a minute past eight and two weeks before our arrival to La Fabrique and Remy and I blistered out of Catalonia for our ambitious twelve-thirty rendezvous north to Cahors with Le Vent des Jours’ biodynamic winegrower, Laurent Maure. The low mountain pass of Le Perthus between Catalonia and France, with the 17th-century military fortification, Fort de Bellegarde, overlooking the goings-on below, seemed a perfectly suitable imaginary line from one nation to another. When I cross borders, I sometimes get a hollow, sinking feeling, like I’m guilty of something (indeed, always of something) and they will nab me somewhere down the road, and this was the first time in years since heavily armed guards were nowhere to be found at the first péage. But two months later, upon returning to the same gate in February on my way back to La Fabrique, I found that that new way of doing things had reverted. A full shakedown from machinegun-wielding but polite children in police uniforms, which included a rummage through my cooler of fresh Tuesday morning Costa Brava mackerel, castaña-fed Galego chuletones de cerdo, and a bottle of Stéphane Othéguy Côte-Rôtie. Sonya is crazy about Côte-Rôtie but prefers them rustic, minerally, sans barrique neuve—a journey to her Lyonnaise roots.

At Narbonne Remy and I took a left on the endlessly long tease of the A61. It seems like the highway design engineers intentionally hid all the best parts along the road: the majestic snow-packed north face of the Alpine-era Pyrenees, the Haut-Languedoc National Park, and a clear view of Disney-like Carcassonne, with everyone nearly swerving off into oblivion as they try to steal a glance. But I’ll take this side over the Spanish side on the highway from Catalonia to Portugal any day, and the long drives on either side of the Pyrenees provide lots of time to talk. When you have a travel companion with a shared love of cooking and food culture and an equally weak resistance to the wine trail’s many once-in-a-lifetime dishes, time passes quickly and the conversations always build the appetite.

Just east of Carcassonne, the historical argument starts. Remy and I were headed into the hallowed ground of cassoulet, where an ancient and hotly contested debate continues about which is the birthplace of the real version: Carcassonne, Castelnaudary, and Toulouse, each claim ownership of the medieval prototype, though I’ve seen Castelnaudary cited the most frequently.

Two months later, before Sonya and I would begin our cassoulet, I would ask, “So which of the three makes the best cassoulet?” “Toulouse,” she quipped. To prompt more explanation, I asked, “What about Castelnaudary?”

“Have you ever had a cassoulet in Castelnaudary?”

“No.”

“They’re awful …”

The cassoulet controversy mirrors Spain’s paella dispute. Where does paella come from? Valencia? Catalonia? Andalusia? It seems universally known to have originated in Valencia. But like cassoulet, paella is more about what you want it to be. Though cassoulet needs the beans, and paella needs the rice, the basic ingredients and technique are the most crucial elements. In cassoulet, some use lamb, some don’t; some use breadcrumbs, while others are offended by the very concept. For paella, it depends on regional production—there are more from shells and fins by the sea and the once feathered and furry in the mountains. The texture of the rice? Another argument altogether …

Cassoulet is one of the world’s great communal feasts. If I want my wife to join me for my cassoulet experience, it must be skimmed of fat (sacrilegious to the French). I wouldn’t dare sneak in pigs’ feet or skin, and leave to chance anything slightly firm and gelatinous; any ambiguous floating piece is met with subtle indignation on her part, skeptical inquisition as to my judgment, and an inevitable transfer of it from her plate onto mine.

While standing in line for a sandwich at one of those French roadside feed lots, attractive single-portion-sized cassoulets in traditional clay pots caught our eyes. We were tired and hungry, and it was cold—around 2°C. We wondered if either of us would go for it. In the rainy and cold weather, cassoulet would be epic and would undoubtedly warm our spirits and prime us for our first visit. But a question on the other side of the Pyrenees would be if we saw a paella in a roadside stop that looked worthy of consideration would we have gone for it? We ordered sandwiches …

Before the center of Cahors and the wildly meandering Lot, we took a left and began our gradual ascent toward Villesèque to Laurent (Lolo) Maure and his biodynamic domaine, Le Vent des Jours. Winding through untamed forest and carved limestone passages with layered lithified sea creatures immortalized 150 million years ago, the sky was gray, the cold wind biting and the drizzle stinging, the limestone also ashen, wet, and uninviting, we arrived two minutes early after our four-and-a-half hour drive. Inside, their party hall was filled with duck products, countless hanging glasses, cigarette smoke (expected), wood smoke, the sound of Bowie on vinyl, and that salty, fatty, and familiar collagen-infused air, we were warmly greeted at the door by Pollux, a wiry-haired black and tan mutt with the same tight frame and graying beard as his manager, who followed with a smile.

Cold and ready for our blood to circulate again, Lolo ushered us to the woodburning stove to unveil his days-long work: piping hot cassoulet (f… yeah!), bubbling in a porcelain-lined cast iron pot. Overjoyed for this perfect lunch, we were quickly led like bulls, pulled to the cellar by the nose as he lamented that he hadn’t prepared the cassoulet for us in a traditional clay pot.

“How does it cook differently?” I asked. Without answering, he deflected with, “You don’t have one?” And I thought, I do mine in porcelain-lined cast iron pots too … (I learned later that aside from the cultural experience, clay pots better distribute the heat more consistently than cast iron.) Lolo walked me to an empty backroom hallway under renovation. He rummaged and pulled out a beautiful rustic clay pot, glazed inside, raw baked clay on the outside, and held it out. “For me?” I asked. “Yes!”

Few objects could mean as much to me as an authentic traditional cassoulet pot with scars of experience, especially a gift from a winemaker I admire. I can only imagine the magic produced in that pot, and I marched straight it to the car to make sure I wouldn’t forget it. This pot was about to leave its cozy comfort zone, travel all over France, and wait with Sonya for my imminent baptism in her version of real cassoulet.

Too wet and cold to fool around in the vineyards, we stayed in the cellar to taste the promising 2024s. We started with C’Juste, a 90% Gros Manseng and 10% Ugni Blanc grown in amphora, destined to be without a milligram of added sulfites. It’s a testament to what can be achieved with no added sulfites in white wines; in fact, no sulfites are added to any wines at this domaine. Some in the natural wine world seem to have figured it out on whites, and they can be raw, charged, and clean. We ran through the various plots of Malbec for the fabulously balanced and charming Les Calades, and finally to Les Moutons, only made in the best years from the top of the hill on the rockiest parcel, groomed and fertilized by a group of miniature pudgy sheep with stringy black and white hair.

Once again closer to the prize, we sat and tasted a series of Cahors vintages dating back to 2018, the first year after he bought the vineyards from celebrated naturalist and biodynamist, Fabien Jouves. Each year was distinct, and because of Laurent’s soft hand with the use of barrels ten years old or older, along with Tava amphoras, concrete and steel, each with varying degrees of micro-oxygenation (or none at all), the wines perfectly reflect each season’s particularities.

Laurent describes it as a “shit year.” I take this to mean, “Everything was hard.” On the horizon for the States is the 2021 Les Calades, a wine that shows its wet and cold season and the extensive care it took to preserve the good health of its few grapes. He’s quite proud of the result, and rightfully so; surrounded by fuller, riper wines, it’s an outlier. 2021 is for those who want less embellishment of this exuberant variety from the sunny years and more sting and verticality. It’s a direct extension of the high altitude, rocky terrain and spare topsoil without the concentrating and sweetening effect of the sun. 2020 and 2022 are fuller, juicier, and easier for anyone to love, and while they’re no-brainers, 2021 is a brainer. We know the difficult years separate the true talents from the fair-weathered geniuses. It’s the toil of the 2021 that made it a success.

Laurent builds on each year’s strengths rather than overcompensating for its weaknesses. The only difficulty during the tasting was the distracting and inviting smell of the cassoulet behind us on the stove. When we finally dug in, it was so tasty and collagen-rich that my lips got chapped from so much licking off the rich and starchy glycerol broth between bites. Any of the world’s greatest wines could’ve been in front of me and it would’ve been just as hard to focus until my plate was clean and I was stuffed. I wanted to finish off the whole pot and Pollux it clean.

A solid food coma set in as we began our westward journey. Remy drifted in and out of consciousness, and I was charged with keeping us alive for the three-hour country drive in the dark. We finally arrived in Bordeaux and were stuck in traffic in the rain and the chaos of the city’s seemingly endless, non-stop road construction. We were an hour late for our dinner with Matthieu and Bénédicte, the makers of our no-added-sulfite, organic and biodynamic certified, non-AOC Bordeaux, Sadon-Huguet. This husband-and-wife team responsible for overseeing production at nearly twenty châteaux under organic and biodynamic practices started their own project in 2018, their red a blend of 60% Cabernet Franc from the limestone-heavy section of Saint-Émilion with the remainder Merlot. It’s an hour’s drive to the northwest in Blaye, on what they describe as an identical geological setting to their parcel in Saint-Émilion. Because they are both firsts in their family in the wine business, buying established vineyard land in Bordeaux isn’t a realistic option, so the parcels are rented from two of their biodynamic growers.

“It wasn’t always about the quality of the terroir,” Bénédicte said when asked about why a good vineyard parcel such as the one they’ve isolated in Blaye has the same guts as Saint-Émilion but just across the river from Saint-Julien and Margaux is without a higher classification. It’s a familiar story commonly heard in Europe’s new generation of growers scouring the lost, forgotten, or perhaps never-explored areas.

Blaye is massive compared to the appellations across the river. It wasn’t necessarily that Blaye (and even Pomerol, a historically a small-grower appellation without much of a tie to aristocracy, and Saint-Émilion, which was spurred into greater production by monastic orders to produce for local consumption rather than global commerce) was incapable of producing high-quality wine back then. It was the historical class division, the trade advantages and the focus of the aristocracy whose economic power developed the left bank. This shaped Bordeaux’s reputation and ultimately a series of classifications that began a centuries-long self-reinforcing cycle of success, much like that of New York’s financial infrastructure, Silicon Valley tech, and Hollywood’s film industry.

Mathieu and Bénédicte followed the vein of limestone and created one red wine from Bordeaux called “Expression Calcaire.” Like many of the world’s great reds, it walks a calculated line on volatility, bringing up the x-factor and highlighting the tucked-in fruit of this fully formed, broadly and deeply complex, no-sulfite-added Bordeaux. Their interpretation through biodynamics, organics and no additions is singular and exciting. It’s full of life and expression with a tightness they attribute to the limestone.

With some fabulously unique and noble qualities, I can’t ever remember tasting before, Remy and I were treated to an impromptu cellar blending trial for their new white made from Semillon. It was recently bottled and will hopefully make it to our shores in 2025. This wine needs to go straight to the Michelin tasting menus.

Yet another long haul ahead, we left our morning vineyard visit and cellar tasting with Mathieu and Bénédicte, for Muscadet. Our stop was in Mouzillon-Tillières with Alexandre Déramé, the nearly one-man show at Domaine de la Morandière. Morandière is a special site on the extremely hard igneous rock, gabbro, with varying depths of topsoil. Usually released six years after its vintage date, the old-vine bottling, Les Roches Gaudinières, grown on gabbro, is structured and expansive but tight and impenetrable when young. He also runs another domaine in Saint-Fiacre-sur-Maine on granite, called Domaine du Moulin. The wines from each domaine are made in the same way (usually in underground glass-lined concrete vats) and they support the argument for the influence bedrock has on wine. Those on granite are much gentler than those grown on gabbro, which are more robust and sturdy.

Alexandre has been with us since we started our company and has been nudged into organic conversion with some of his top parcels. He began to test it out a few years ago, and you couldn’t pick a series of more difficult years than 2021 through 2024 to keep a new convert’s confidence in the organic process. Though still on board, 2024’s destructive mildew pressure tested his faith, as with almost every non-conventional grower in France. It was an extremely difficult year and many of our longtime organic growers lost nearly all their crops. 2025 needs to be fruitful (no pun intended), otherwise we may see the collapse of some of organic farming’s most faithful.

When we extended our reach beyond the California border, it seemed that every tuffeau fragment of Loire Valley had already been overturned. It wasn’t only picked over by other importers, but sommeliers were also posting unknown growers on social media long before they found representation in the US. This prompted many importers to follow those with wide reach and sprint to nab the grower. After the growers in Brézé attracted more interest in Saumur’s dry Chenin game, a mad dash of importers to the area was in full swing. We were once at the front of the line, but by the time we branched out, we found ourselves holding up the rear.

The beginning of Chenin’s most recent dry wine renaissance took shape a decade and a half ago in Brézé. In 2011, Arnaud Lambert’s Brézé wines were on our company’s first container. Buyers couldn’t reconcile the electrical charge of Arnaud’s entry-level Saumur white under the Château de Brézé label, which was composed entirely of the historic Clos du Midi fruit at the time but not noted on the label. We had a hard time selling them, but two years later, with Guiberteau’s wines on one of our boats to California, people took another look at Arnaud’s wines, and we were off to the races. Even if our relationship remains good, our collaboration with Romain ended a few years ago. But Arnaud, the quiet and largely uncredited spark that contributed to the explosion of Brézé, remains a cornerstone of our California identity. So, where to go after Brézé?

If terroir is one’s guide, Puy-Notre-Dame could be one of the next hot spots. Further south of Brézé, there are a lot of different hills just like it: tuffeau limestone outcrops that survived flood erosion and are spread apart by vast lowlands used for other crops along with vineyards. The areas of Puy-Notre-Dame are visually unimpressive, but so is Brézé and Saumur-Champigny.

At the risk of sounding naïve, my original notion of being an importer was to seek out these nearly forgotten terroirs, and the quiet, hidden talents tucked away in corners. Success stories like Arnaud Lambert can also be found in what may seem like unlikely places; places that, in truth, may be the most capable and thrilling of all. That spark may be hidden within an imperfect, seemingly mundane wine that leads you in an unexpected direction. What first appears average may hold just a glimmer of brilliance, or the faint, familiar scent of a gifted terroir, of something remarkable, that’s somehow and miraculously been overlooked.

There is no greater satisfaction for me as an importer than contributing to the success of humble and curious people. Sometimes their open minds only need a well-timed nudge. For better or worse, I’m a nudger. Most average bottles lead to a dead end, but occasionally I find some sparks too bright to ignore. Excellent cellar skills and how to farm well can be learned, but if humility and curiosity aren’t ingrained in one’s youth? A lifetime of therapy is in the cards …

Four new growers around Saumur signed on with us in the last two years and each holds promise in their unique way. Our first visit during this trip to Saumur was the historic Puy-Notre-Dame domaine, Forteresse de Berrye. Purchased in 2019 by Gilles Collinet, a botanist who owned several organic nurseries, it was immediately converted to organic viticulture. After I saw the potential in the vineyards and Gilles’ seriousness in elevating his new property to a world-class level, I suggested he connect with Arnaud Lambert’s consulting enologist, Olivier Barbou. Olivier joined him immediately, and the following year Gilles also signed Loïc Yven as their new Chef du Culture (vineyards manager), who was at the time with the Nady Foucault consulted project, Domaine des Closier. Gilles lucked out with this historic property, whose ancient military base and vineyards are perched above the expansive territory and have a great view of the surroundings. While the lower areas are a mix of unsorted alluvium and capable of rendering good wines, their complexity has limits. The key to all the exceptional wines in the region is that magic sandy tuffeau limestone rock preserved above these ancient flood plains and in contact with the vine roots.

Their new 2022s (with new labels) have just arrived, the first season under the gentle guidance of Olivier. After more than fifteen years of exploration with Arnaud, Olivier’s experience and touch is evident. He also understands Gilles’ predilection for wine, which is aligned with mine: pure, raw and focused without artifice and over-stylizing. With lesser terroirs this approach is perhaps less interesting, but like the highest quality fish in the hands of a sushi master, wines from fabulous terroirs need to be let alone and served unadorned to highlight their quality. Gilles cleverly explores his vineyard’s potential through this more naked state to better understand where the most promising plots are and how to bring out their best.

The racy, chalky, citrusy 2022 Crémant, made entirely from Chenin Blanc with a dosage of 5g/L is the first in line for the newly arrived wines; the first batch of bubbles from the domaine blistered out of stock and into the market in a heartbeat. The 2022 Saumur Blanc “Les Bourgeres” is classic Chenin Blanc that echoes many celebrated white wine regions of northern Europe. It comes from vines planted in 1993 on tuffeau limestone bedrock with relatively thin topsoil of calcareous silt, sand and clay. It’s raised in only concrete and old barrels of 225-400 liters, and is deeply green, like exotic moss, chlorophyll, reposado tequila, lime and salt with a light honeyed finish. I’ve said since my first tastes of earlier wines even before Gilles took over, they reminded me much more of Vouvray than Saumur, or Riesling with the softness of Sonnenuhr, or Domprobst, with the limestone force of a Keller Von Der Fels. Their 2022 Saumur Rouge “Clos de Berrie” comes from vines planted in 2012. It’s vigorous, high-energy Cabernet Franc with a sturdy and wiry frame, perhaps credited to its tuffeau bedrock below a shallow loamy topsoil rich in calcareous sands. This year is also dark-fruited (perhaps because of the warm summer) and shows some nice curves, though it’s still tightly framed. Tannins are fine but sharp, with balanced green characteristics to compliment the cool and refreshing limestone tension.

The red and white wines showed even better on the second day they were open than on the first. I was going to give them a few tastes and then open other samples on my list to taste, but I couldn’t quite break away. They ceaselessly continued to rise and fascinate even more, especially the white, which, even in this very simple and straightforward crafting, already shows the pedigree of this hill and these historic vineyards.

Another smaller-scale head turner in Puy-Notre-Dame is Frédéric Haus and his Domaine Les Infiltrés. All his vineyards are in the village of Puy-Notre-Dame and are under organic culture. “I left a comfortable situation as a senior technician in the cinema in Lille, a city of heart, to take care of a piece of land with organic farming, and for 20 years I was a committed and enraged social and environmental activist. To speak from agriculture and out of phenomenological concern and to save the environment, I decided, like many, to occupy it …”

Fred’s initial wines were unusually successful initial endeavors. It was 2021, also his first year involved in any viticultural activity. It was also the first year of Chenin Blanc and Cabernet Franc I tried from him before we signed on, eventually importing his 2022s. Fred’s background in craftsmanship and art is felt in his wines. But more than the aesthetic of craft, he’s looking for emotion, and his wines find it. On our day with him, his new wines had just been bottled and were hard to read. But with the bottles shipped to me in Spain in January and tasted in February, I’m even more convinced of this guy’s talent. The 2022s have just made their way to New York for their first showing. Heads will turn, even in markets that have heard every pitch under the sun: some things are still uniquely beautiful enough to grab our attention.

Hiding in Brézé under everyone’s nose was Fabrice Esnault’s Domaine la Giraudiere. Most of Fabrice’s viticultural life was spent building business for the negociants by selling from his production of twenty hectares and only a little in-house production to sell at his tasting room. All that was needed was a label change and a little nudging from us (and our mutual friend, Arnaud Lambert), and he would walk through the door with us.

Our visit with Fabrice was another moment of confidence for us and this investment on both sides. The new 2023 wines out of vat were promising in the spring, and when I tasted them with Remy in December they had found solid footing. What I like most about his wines is their directness and simplicity in the way they’re styled. The whites taste as much Brézé as any from the hill because the grower hasn’t overthought or overwrought them in the cellar. During our cellar tasting, Remy asked about a mostly spent unlabeled green bottle with a white wax top. It was a Chenin from Brézé made by his father in the 1990s. Remy asked if we could try it, and Fabrice grabbed another one. It had a perfect platinum hue like it hadn’t aged more than a few years and still had a full tank of gas, simply spectacular. The taste in that bottle was what everyone should be pursuing: unadulterated purity!

My spring nudging (the second or third attempt, I’ve forgotten) about conversion to organic farming with Fabrice took root. He already has a parcel under organic generically bottled as “Brézé,” but there will now be many more to come in time with Ardillon the headliner. His stable of reds comes from Saumur-Champigny in the communes of Montsoreau and Turquant. Like the whites, they are also crafted to express their distinct terroirs rather than bamboozle with the sleight of hand in the cellar. For a classic style approach, Fabrice is one to watch.

The scene was set early on in Portugal. It would be my second visit to Carole Kohler, and Remy’s first. I pulled her 2022s out for dinner before we flew from Porto to Barcelona. It was as convincing as I’d hoped, and Remy was excited to see this place and this person I’d already mythologized before a single drop of her wine had ever been poured in the US.

Sometimes you know instantly when you’ve gotten lucky, again. Like my first Lambert Chenin from Brézé in 2010. Thierry Richoux’s 2006 Irancy with the Collet family over dinner in Chablis. Veyder-Malberg’s first Wachau wines at his house in 2010. My first Dutraive Fleurie in New York, in 2013, poured blind by my friend–a true sommelier, Eduardo Porto Carreiro. Cume do Avia’s 2017 Ribeiro reds over lunch in Sanxenxo. My drop-in visit with the unknown Daniele Marengo was at his family’s cantina in Barolo. My first two wines from Carole are part of this list.

When I first tasted her enchanted forest, biodynamic, baby-vine 2022 “Source” Chenin Blanc and 2022 “Jardin” Cabernet Franc, I thought, “These are too good.” I yelled to my wife from the kitchen while preparing dinner, “It’s impossible that no one works with her in the US … You won’t believe them. They’re crazy!”

My tasting notes were filled with exhausted references to the great producers in every other sentence. I’ll spare you what would seem like hyperbole and all-to-often exaggerated comparisons to the world’s elite everyone uses as context to sell their new wines these days, but let’s just say that Carole’s are aligned with the world’s best raw wines—no direct references needed.

After drinking her wine for the first time, I tried to maintain a poker face for our call. I distracted her with inquiries of how she made them, about the vineyards (“schist, silex and limestone all in three different plots only hundreds of meters away from one another? Really?), and finished with, “How much sulfur did you add?” “None,” she responded without explanation. Then she asked what I thought. I let her have it. “They’re just incredible … How are importers not swooning by the dozen? Have you never sent your wines to a US importer before? No sulfites, at all?” (In 2023 with a few of her wines, she added a mere 10 mg/L to mitigate some risks for what she describes as a challenging vintage. None of the 2022s have added sulfites.)

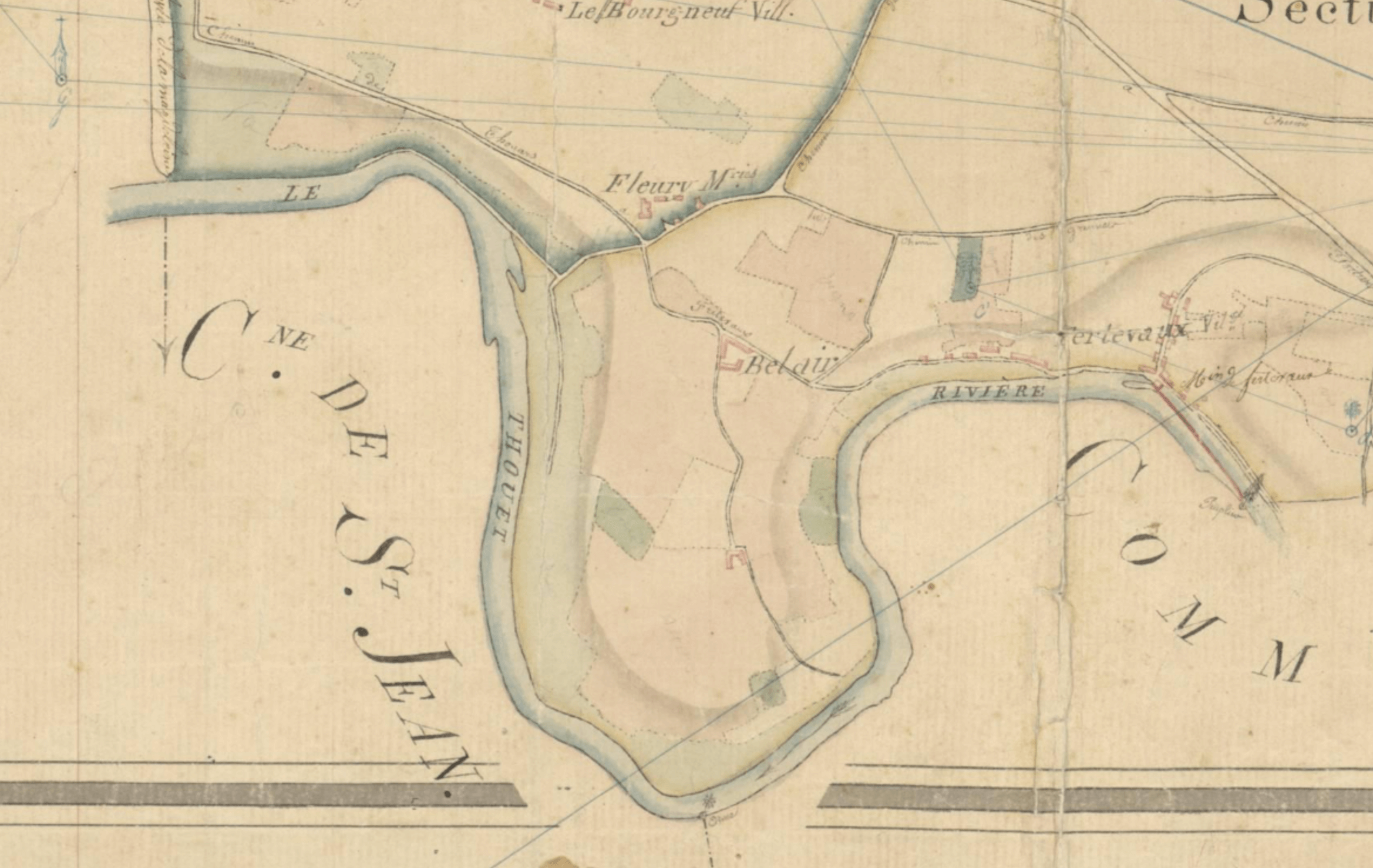

So why hasn’t anyone snatched the place? First, it’s new—well, kinda. Fleury does have history, though it might’ve been forgotten for a while. Carole’s viticultural renaissance of Fleury, an estate documented back to 1458, and then again in 1753 as a fiefdom (land grant from a lord) of the Dukes of Trémouille, began in 2016 with its first vines rooted since at least the 1960s. Registers kept in the Municipal Archives of Thouars demonstrate that vines were cultivated in Fleury long ago, with the oldest registered in 1930. But many European registers for various things were only started sometime in the 1900s, to make sure people planted with American rootstock, and to fall in line with incoming appellation laws, among other things, but most importantly the desire to have a greater tax regulation on wine. We’ve seen this a time or two with old vines in certain areas, like Spain’s Jimenez de Jamuz, whose register says that all the old vines there were planted in 1930, but the locals know they’re much older—some pre-phylloxera.

Secondly, it’s located in the greater Anjou AOC and almost nobody is poking around on the edges away from the most celebrated areas of Anjou, like Coteaux du Layon, or Savennières. This generations-long family home of her husband, Brice Kohler, is a dull 35 minutes south of Saumur center, 30 from Brézé, and 22 minutes from Puy-Notre-Dame. It seems to be the last area to discover on the frontier of the appellation for quality wine. The vineyards are in the former Vins de Pays Thouarsais, an appellation discarded decades ago during the EU’s consolidation of appellation regulations, along with most of the interest in this once-important wine region before phylloxera. Today, it’s lumped into the generic “Anjou” appellation, and the Kohlers forgo the appellation altogether in favor of an even more generic Val de Loire appellation, to be even a little more self-exiled. Many vineyards in Thouars were destroyed in 1964-65. The government paid owners to uproot because they were at the gates of an expanding city, with many pre-empted to build the city’s bypass and large commercial and residential areas. This all seems like such a blasphemous offense to Dionysus, and they were surely punished for it as the wine trade basically disappeared. The financial incentives of the time were too low, the same as in most of Saumur’s generic appellation until the last ten years. If you hadn’t recovered twenty years after WWII ended, maybe it’s time to move on. History shouldn’t be forgotten, and at Fleury, it wasn’t; it was recorded quite well. It only needed the right people to dig up the records.

Fleury was established in the 15th Century around its constantly flowing spring between the front gate and the house. Joined at its western hip to the ancient city of Thouars, the 16th Century house is quaint, well-kept, remodeled timelessly and full of artifacts, and beautiful art that hardly leaves an open space on the walls of this idyllic storybook countryside manor in France’s north. There’s a maze of cellar underneath, a small, freestanding winery installed in one of their old storerooms and animal shelters, a beautiful, long greenhouse dating back to 1870-1900, 19th Century gardens and a sizeable amount of ancient indigenous forest (suggested by Carole as perfect for Shinrin Yoku—Japanese “forest bathing” to clean the mind). Some exotic trees were planted through Brice’s family of five resident generations (including a sequoia in 1877), an untamed and undeveloped riverfront property, and an extensive horse pasture where Finley and Léon spend their days grazing. It’s almost too perfect with its separation from all other agricultural fields by trees, and without another vineyard even close. Its four separate vineyards gain a unique and lively biodiversity without neighborly intrusions from possible conventional farming activities disrupting her organic and biodynamic practices. It’s hard to imagine that when people figure out how good her wines are some of them won’t also consider planting around Thouars.

Perhaps a third reason she was overlooked was that 2018 was Carole’s first year, ever. The 2020 and 2021 wines they opened to taste along with the 2022s and 2023s were well beyond just that “glimmer of misdirected brilliance and the faint, familiar scent of a gifted terroir somehow overlooked” that was mentioned above. But I didn’t find the same level of clarity as the 2022 Jardin and 2022 Source. Something else clicked in 2022, perhaps they just needed five years to find that line.

And then there is Carole Kohler, the subject of a Klimt painting who slipped her frame. In constant reflection of light in motion, seemingly unaware of the energy with which she fills every room and every vineyard she enters, she leans in, listens like it matters, and smiles easily. There’s no distance with her, no pretense, no guarded elegance. She cooks with inspiration. There’s so much art and sculpture in their house that everything seems to be alive and moving. She’s an avid reader, skier, runner, swimmer, and yogi. “I also like meditation, sewing, decorating my house, and taking care of my flowers and my family.”

After her university studies where she attained a Master’s degree in Chemistry followed by fifteen years in the agri-food industry, Carole felt it was time to “Reconnect with the living and give meaning to life … to live with the rhythm of the seasons, immerse myself in nature, produce a local and shared wine and work to guarantee the sustainability of the Domaine de Fleury, owned by my husband’s family for five generations.” She added, “I can’t really explain why it was like a little voice telling me that I will be happy doing that…” Committed to her newfound idea (and giving in to the voices in her head), she went back to school, attaining a diploma in Viticulture at Montreuil Bellay, just twenty minutes north on the way to Saumur. During this time, they also had their selected plots analyzed through pits and generated detailed geological maps and bedrock and topsoil compositions of what they stood on before they began to plant.

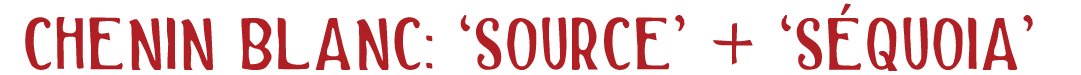

A working architect by trade, Brice met Carole through his sister when they were teenagers and is the other half of the dream to revitalize cet endroit extraordinaire. His desk overflows with a collection of ancient, illustrated maps and today’s geological research of the area that supports its rich heritage as a transitional center of the Massif Armorican and the Paris Basin, copies of vineyard registers, documents of Fleury’s history as a fiefdom and declarations of harvest from the 1930s. Together, they shared the same curiosity and belief that this was indeed a place!

A walk inside Fleury’s vineyards is a walk in what seems like virgin green land flowing uninhibited with yellow, purple, pink, and red indigenous flowers and a multitude of competing grasses that make it hard to walk through the fields before their annual plowing. These flowers are usually only around during the months one would expect, but as mentioned in last month’s newsletter where we covered the portion of our trip in Spain, there were also spring flowers in bloom in the Loire Valley mid-December! Carole notes that when the vines are young, they need more plowing to ensure the root systems head downward instead of sideways. Tree groves abut each plot, bringing an orchestra of fresh wind and foresty smells with the constant rustling of leaves and the buzz of bees and bugs.

After Jardin was planted in 2016, Source was planted in 2017 entirely to Chenin Blanc on a single 0.7-hectare parcel at 70 meters altitude. It sits across the little one-car road, Rue de la Mare aux Canards (Duck Pond Street), which marks a clear separation of the acidic rock of the ancient, Pangean-era Massif Armorican from the alkaline limestone rocks of the Paris Basin. On the south side is the 570-million-year-old Precambrian quartz-rich schist and micaschist outcrop above the Thouet River, and on the other side, the white limestone. This is evident on the road’s walls, cleverly distinguished by its builders, who built the southwest wall with the dark gray and green schist from that side and white limestone (an occasional dark blue schist for accenting) on the northeast wall.

Named after the spring that led generations to inhabit the space around it now known as Fleury, Source is dynamic and quite distinguished from the other Chenin Blanc on the property, Séquoia. Its topsoil is rich in quartz and grey schist with clay on a green and black schist bedrock. This is an explosive white with more muscular, mineral-heavy lines. The 2022 was fully matured to 13% potential alcohol before picking and is a must-try from this domaine as it represents what is possible with this extremely talented site. By contrast, the 2023 was picked very early because of vineyard challenges from botrytis in September. Carole explained that with its proximity to the river, only 50 meters away, and the thick forest in between, she couldn’t wait another day for fear of losing too much crop to rot. It was picked, not chaptalized (as so many would do without a second thought), and bottled with 10.5% alcohol. Even with this low degree of alcohol, it offers extremely fine lines but without the same explosive solar-powered energy of the 2022 version.

Just a hundred meters east of Source are the two parcels planted in 2019 that constitute the 1.5-hectare plot of Chenin Blanc for Séquoia. Once again, we are in the Pangean remnants of the Massif Armorican with a topsoil of clay and decomposed schist and quartz on very hard green mica schist bedrock. With only a few vintages to draw from, Séquoia appears to be more linear and finer than Source, in general. It’s not as explosive but offers a distinct contrast, indeed worthy of bottling separately.

The 2022 Source was whole-cluster pressed and naturally fermented in 30-hectoliter steel tanks for four days at a maximum of 23°C and completed malolactic fermentation. It was bottled with no added sulfites and was not fined nor filtered. The 2023 Source and 2023 Séquoia went through the same processes as the 2022 Source, except that they were aged in 12-hectoliter clay Vin et Terre amphora and old 225 L French oak for eight months before bottling with 10 mg/L of total added sulfites. Neither were fined or filtered.

As good as Carole’s Chenin Blanc wines are, her Cabernet Franc hooks you immediately. Incredibly alive and full of energy, its red and black fruit profile has a lean fleshiness snugged up and narrowed by a garrigue-like floral bouquet of lavender and flowering wild thyme and a core of deep earth and virility. It’s complex and hard to square that it comes from a half-hectare of baby vines planted in 2016. This is the fruit for Jardin, whose vines sit on a mild slope facing west on the Paris Basin side of this geological convergence. While there are both Jurassic and Cretaceous limestones in the greater Anjou area, the bedrock here is what geologists call, Toarcian (named after Thouars!), from the Early Jurassic dating to around 180-million-years ago. This hard clayey limestone doesn’t share much in common beyond its dense calcareous materials with the Loire Valley’s much softer sandy tuffeau limestone, though it does have some sandstone interbedding. It’s less pure in calcium carbonate, and more relatable to the limestones of the Côte d’Or, though it predates the Côte d’Or’s predominant limestones by around ten million years. It’s like Bathonian, Bajocian, and Oxfordian, among others, though Toarcian limestone may be found in some appellations—and Chablis’ Kimmeridgian marls are about thirty million years younger, while Portlandian limestones predate it by about forty million years.

The upper section of Jardin sits at 90 meters with shallower rocky topsoil of silex, limestone, clay and sand before striking a hard and fairly siliceous limestone bedrock (in this case, with black flint/chert) at 30 cm below. The topsoil deepens lower on the slope reaching down to below 80 cm where some influence of the river is apparent with deeper alluvial topsoil, making it a longer but easier journey in search of limestone bedrock. All this is to say that Jardin is complex, and some of that complexity could be attributed to its geological diversity inside this small parcel.

Jardin is destemmed and naturally fermented in 50hl stainless steel tanks for 15 days with no extraction movements (infusion method) at 25°C maximum. It’s then aged eight months in old 225 L French oak and concrete eggs and bottled with no added sulfites and without fining or filtration.

“You don’t want to taste my rosé?” Carole asked. My first thought was: The world needs Cabernet Franc rosé like a vigneron needs late spring frost. When the 2023s were finally in bottle, I asked her to send me samples of the 2023 Source, Séquoia and Jardin. The bottles of Source were missing from the box. In its place were two clear glass bottles filled with a hazy, faintly rusty, warm, amber-colored wine inside, with labels of a cartoon Carole, red-headed and her face pastel shades of golden yellow, soft coral pink, deep orange and red, with one big eye peering through a marigold wine glass. “Carole, you sent me the rosé.” “Well, lucky for you. I’ll send Source next week.”

I didn’t want to spoil my impression of Carole’s great range of wines with a Cabernet Franc rosé, so the bottles sat unattended for three months before Remy arrived. “What’s this?” He asked, emerging from the parking garage after rummaging through my wine storage there. “Cabernet Franc rosé.” “Oh …” We pulled the cork anyway. Before I took my first sniff and sip, I saw a light go on in Remy after he’d tasted his and I knew I’d made yet another incorrect assumption.

Carole’s rosé is bottled summer sun. I never thought a Cabernet Franc could render such a dainty, attractive beauty. It’s soft and pretty, lifted with pink rose petal and taut stone fruit skin, just the right touch of amare from the light extraction and thrust from Cabernet and Chenin picked just a touch earlier than grapes for her other wines—an equal mix of both varieties.

Whole-cluster pressed, naturally fermented at a maximum of 18°C for a good balanced fruit and savory notes, and aged for six months in 12-hectoliter fiberglass. It undergoes full malolactic and has no added sulfites, finings or filtration. The Cabernet Franc portion comes from a single 0.3-hectare parcel planted in 2020 at 75-80 meters altitude, just across the Rue de la Mare aux Canards and slightly uphill from Source (where it takes the Chenin Blanc of the blend) it’s on a mild slope facing southwest. Across this one-car street, from the first Chenin vine to the first Cabernet vine, the mica schist soil of Source changes to Toarcian limestone bedrock and clay topsoil—Precambrian Massif Armorican to Jurassic Paris Basin, a 360-million-year geological swing in less than ten meters.