We all share the belt-tightening sensation of tax season, or at least most of us do, and I’ve made it a habit to be on the wine trail during this time to avoid the stress as much as possible. Without my team back home, spearheaded by my sister, Victoria, my escapades around European wine country would be impossible, and taxes usually make April our slowest sales month. We don’t expect that to change, so we ordered somewhat less a few months ago in hopes that we would time things just right (an almost impossible task with these months-long delays) in order to have only a few gems to show around while budgets are reduced. Somehow, the timing worked out, so we don’t have much arriving, though I’m very excited about the wines that are coming into port.

While I was tasting through Anthony’s range in his cellar last summer, I was caught off guard by how little bottled wine there was inside his new stockage, next to his new house in Villié-Morgon. Despite the pandemic, global interest in Anthony’s wines increased immensely in recent years and his cellar was nearly cleared out. There wasn’t a line out the door waiting to put in their reservation, or the phone ringing with others that would squeeze me out, but I couldn’t get through our tasting fast enough to jump into securing a sizable allocation on the spot. Some wines, like the 2020 Côte du Py, weren’t even released yet, but I pushed to get on the boat before it sailed. This resulted in us acquiring four different vintages at once, a good opportunity to explore some insight on his development, from four warm seasons in a row that experienced different circumstances. I’m not surprised by the increased demand for his wines. From our first meeting and tasting, his imminent rise to Beaujolais stardom seemed obvious. Anthony Thevenet started out on the right track; prior to his first vintage, he worked a few years in the cellar of the natural wine luminaries, George Descombes, followed by a half-decade in the cellar with Jean Foillard. While still working with Foillard, he made his first domaine wines from the 2013 vintage, a lovely year for those of us who adore fresh, taut and bright Beaujolais wines. Anthony’s gorgeously subtle 2013 Morgon Vieilles Vignes and the 2014 that followed were a fabulous omen for the future of this kid crazy about motorbike sports and wine. The 2014s seemed to be a shoo-in for everyone in Beaujolais due to its beautiful balance and clean and pure perfumes.

Thevenet’s third year, 2015 was filled with behemoth wines and this harvest tested the efficacy of picking teams to get the fruit off the vines as fast as possible. The fundamental challenge of logistics remains the difference in some years from good to very good, to great, even with top growers. Often, nuances that stick out from a wine today, like desiccation of fruit, discreet green notes, austere tannins, or a lack of acidity are the result of challenging logistics during grape harvesting by hand and the need to collect as much as possible before the problems are really exacerbated. When the grapes are ready to go, you better be ready with a committed team that knows what to do! 2015 was a big year for everybody, but for some, it was a banner year. With a higher-than-expected alcohol and ripeness level, the grapes inexplicably maintained balanced acidity with a good mixture of red and black fruits. While roaming the streets of Los Angeles, before the release of his 2015s, I pressed Jean-Louis Dutraive about his honest opinion on the vintage, and, to my surprise, he said that 2015 may be the greatest year of his lifetime. (If you’ve not spent time in Beaujolais with the growers, at least in Morgon and Fleurie, you should know that these guys like to drink, and many, even the top growers, often don’t seem to concern themselves about alcohol content as much as they do about balance in their wines with whatever the season dicatates.) Overall, in Beaujolais, it’s all about what you, the consumer, wants from the wine. Some vintages can produce monsters, while others are dainty and flutter. I have not yet tasted better 2015s than Anthony Thevenet’s, but I stopped tasting many of them once the 2016s came around.

2016 was hit or miss, and the hits were solid ones, at least for me. Then it was back to the heat with 2017, 2018, 2019, and 2020, with varying differences between these hotter years. The Northern Rhône, being just across Lyon and toward the south, shares great similarity to these years, as do the lands of Chardonnay and Pinot Noir further north. With climate change, the hot years, especially in continental Europe, are predictably similar to each other, as are some of the cold years, like 2021, where mildew pressure across the west of the continent was insanely high and had a severe effect on yields and quality potential. Today, the difference between vintages teeters on a knife’s edge between too much and too little of what’s desired. With extreme changes in very short periods, wines can easily overshoot their mark in just a matter of a day or two.

Quick Thevenet cellar notes: All the wines are vinified with a carbonic maceration without any sulfur added until just before bottling, and they ferment at temperatures no lower than 16°C. There are no added yeasts, and the fermentations are done in a gentle, infusion style, and can last between eight to thirty days, with the latter more rare and only employed for the top wines. There is no fining or filtration, and the total sulfite levels are under 15mg/L (15ppm). The purity and clarity of each wine’s terroir expression under Anthony’s supervision due to very spare sulfite inclusion are a testament to his laser-sharp attention to detail and instinct in the cellar.

The 2020 Beaujolais-Villages presents an opportunity to see the merit of Thevenet’s lovely Beaujolais range from a year that is often (at least with our producers there) more expressive of red than black fruits. 2020 is a great followup to 2019 in that it was similarly warm, but the wines are more delicate and less decadent and full than the 2019s. There’s everything to love about the 2019s too. They are full-figured and strong in concentrated red fruits compared to the previous years, 2018 and 2017, which both show greater sweet licorice and slight balsamic notes accompanying the mix of red and dark fruits. This Beaujolais is a small parcel grown just outside of Morgon with vines of an average age of fifty years, grown on granite sands and raised in concrete tanks, leading to lifted aromas, a gentle palate, and bright fruit.

In the next tier are the Morgon and Chénas appellation wines. Both wines are made the same in the cellar with 5-8 months (depending on the vintage) in 60hl concrete vats without sulfur until bottling. They also sit lower in the slope areas, which makes for a fun side-by-side comparison of these terroirs. Anthony and his father rent the Chénas vines and do all the work themselves. The slope is soft and slightly tilted toward the north, but still relatively flat. The soils are a combination of completely decomposed granite with different soil grains that either decomposed in place or are alluvial depositions. There are few rocks in this vineyard planted in 1970, except for some large, rounded ones. An interesting consideration between his Chénas and Morgon is that the Chénas granite is much pinker than the grayer granites of his Morgon vineyards. Thevenet’s Morgon appellation wine comes mostly from Douby, a zone on the north side of Morgon between the famous Côte du Py hill and Fleurie, and the lieu-dit, Courcelette, which is completely composed of soft, coarse beach-like granite sands. Much of these vineyards are on gently sloping aspects ranging from southeast to southwest. There are also rocky sections, but generally the vineyards are sandy, leading to wines of elegance and subtlety, also endowed with great length and complexity from their very old vines. The average vine age here is around sixty years, not too shabby for an appellation wine!

Jumping into the upper tier are the domaine’s two flagship wines, the 2020 Morgon Vieilles Vignes and 2020 Morgon Côte du Py “Cuvée Julia”. The general vinification method for these two is the same as the others but often for a longer maceration time, and the cellar aging is also different. Both are aged for seven months in old, 600-liter barrels, but sometimes 225-liter when the crop is too low to fill a full 600-liter barrel. The differences between these two wines are a result of their terroirs. Both have very old vines, with the Morgon Vieille Vignes being from 90–100+ years old, grown on granite bedrock with gravel and sand topsoil derived from the bedrock, while the Morgon Côte du Py “Cuvée Julia” (named after his daughter) is from 90-year-old vines grown on extremely hard metamorphic rock with a spare topsoil also derived from its underlying bedrock. 2020 is a special year for these wines where they return to a brighter style with a little more tension than the 2019s. Of special note is that the 2020 Côte du Py is the last vintage before these old vines were pulled out in preparation for a new plantation. It’s unfortunate, but the vineyard was difficult to farm and needed to be replanted because it was not tended to very well prior to Anthony taking over and converting it to organic farming.

In 2015, I asked Anthony if he would consider making a wine exclusively from the ancient vines in his Douby property just above the D68 on the north side of the hill across from the fields surrounding his family’s home and old cellar. With wide eyes he said, “why not?” And then he did it! The vines that make up the 2017 & 2018 Morgon Vieilles Vignes Centenaire date back to the American Civil War! What an opportunity to taste vines with such history! Like the Morgon VV and the Côte du Py, it’s also aged in 600-liter demi-muids, but for around ten months. It’s spectacular wine and offers a different view into how vine age can truly influence a wine’s overall character. Vinous wine critic, Neal Martin, says about the 2017 version that it “would give many a Burgundy Grand Cru a run for its money.” And there’s only one way for you to find out if this is true, and while the 2018 was not reviewed, it is just as good as the 2017. As one would expect, supply on these two legends-in-the making is very limited.

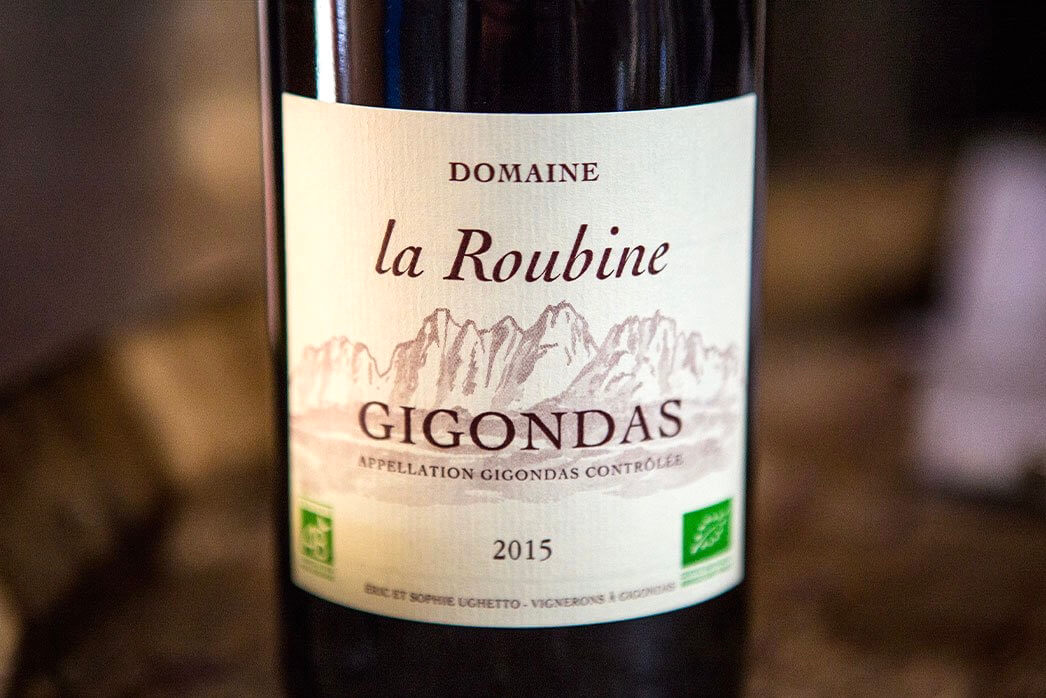

There are few southern French wines that have come in and then blown out of our inventory as quickly as those of Domaine la Roubine. Located in the famous wine village, Gigondas, Eric Ughetto and his wife, Sophie, moved back to their family’s region in 1990, where they took over the family domaine and converted it to organic farming.

Roubine’s style of wine represents the best of the rustic-but-clean vein of European wines. Each are fermented with their whole clusters (already quite different from most growers working with these varieties) for at least a month on the Séguret and Sablet, and for a month and a half for the Vacqueras and Gigondas, an even greater step into the rustic realm! One of the many interesting elements of their wines is that they’re exquisitely crafted, despite all opportunities for them to get too loose in their framework, with higher volatility among other possibilities with this kind of extended fermentation. The pH-increasing whole cluster inclusion with Grenache, a grape with an affinity for oxidation and higher alcohol levels, can often result in brettanomyces, a wine fault (at least in my book) that seems to be almost forgotten in the face of the new rodent in the cellar, mousiness, which is most often found in wines left to their own devices following the natural wine movement dogma.

Starting with the entry-level reds are the 2020 Sablet and 2020 Séguret, two very serious wines at not-so-serious prices raised only in concrete tanks. Sablet, named for its vineyard’s dominant soil type, sand, is a beautiful and quiet satellite village of Gigondas. Perched up on a small hill, its sands were principally brought in by the Ouvèze River coming from further east, through the hillsides at the base of Mont Ventoux. Roubine’s parcel is up off the river valley floor, tucked into a forested hillside on terraces, giving it its own unique personality, and, I would add, its own deeper complexity with its likely deeper connection to bedrock below instead of an endlessly deep sand bed. The grape blend is 70% Grenache, 25% Syrah and 5% Cinsault. The main difference between the neighboring vineyards, Sablet and Séguret, is that the latter has a greater mix of calcareous clays with the same sands of Sablet, resulting in a topsoil that has a yellowish hue and is notably chunkier and whiter with than Sablet’s canvas-brown sands. Both wines are a true bargain for those looking for a middleweight that punches a few classes up, and one would be hard-pressed to find wines from these appellations of such note as these. The Séguret appellation as a whole seems to have a greater possibility for more significant wines, but will likely always be overshadowed by Gigondas and Vacqueras, two powerhouses of the Southern Rhône Valley that can often match the complexity of Châteauneuf-du-Pape, without overpowering it. Roubine’s Séguret is composed of 70% Grenache and 30% Mourvedre, an alliance that imparts a slightly more exotic expression compared to Séguret’s more classically-nuanced savory characteristics. Indeed, both wines are rooted in the savory world, which makes them and Roubine’s upper division wines great for nights of grilling salty meats.

The 2020 Vacqueyras and 2020 Gigondas are, as mentioned, vinified in the same way in the cellar and aged in a mix of mostly neutral medium-sized oak barrels, which leaves their terroirs to do all the talking. Vacqueyras has a little diversity in topography with some vineyards perched on higher terraces on the western side of the Dentelles de Montmirail, with a gradual slope downward in a series of undulating alluvial terraces of reduced steepness. The Vacqueyras, like the Gigondas, is a mixture of terraced vineyards upslope and some in the middle terraces, and is usually the more rounded of the two wines. Often it can steal the show between the two because of its more upfront appeal, while the Gigondas showcases a more serious profile; it really depends on what you want from the moment! The Gigondas comes from two different areas, one up into the mountains on white and gray terraces of limestone, quartzite, clay and sand, and the other on a flatter terrace of iron-rich red clay mixed with galets roulés, the rounded quartzite river rocks most famously associated with Châteauneuf-du-Pape, and which is otherwise ubiquitous in the Southern Rhône Valley.

The result of this combination is a Gigondas of immense depth with all the things we hope for out of this historic appellation filled with many good vinous addresses. It has the freshness of the vineyard high up into the dentelles surrounded by all the herbs of Provence, wild lavender, thyme, rosemary, and many more wild, aromatic shrubs and trees, along with the ferrous-rich palate seemingly imparted by its red soils from the parcel further down above the river plains. If Southern Rhône wines are a part of your annual interests, don’t miss these. They’re truly a bargain for their pedigree and craft, and have their own unique expression from Eric’s choices in the cellar.

More Riesling Trocken from Wechsler is hitting our shores, as well as the Scheurebe trocken wine (a big hit despite a historic lack of interest in this unique grape variety, though we’re not surprised at all), and more of the Scheurebe Fehlfarbe, one of Katharina’s orange wine experiments that has gone very right!

The new wines for the market start with Wechsler’s 2020 Westhofener Riesling Trocken, a wine made entirely from her many parcels in Kirchspiel and mostly from the younger vines. This wine bridges the gap between the Estate Trocken and the Kirchspiel Trocken. It’s friendlier straight out of the gates than the Kirchspiel Trocken and a bit less intense than the Estate Trocken. Like others in this region who have a “Village Trocken” wine, it’s worthy of attention and may be the better for larger parties of people rather than Katharina’s bigger hitters, like the next wine, which simply need more time after opening to show everything they have. There’s more to be discovered about the setting of Kirchspiel in the next paragraph!

We have waited quite a while for the Katharina’s 2019 Kirchspiel Riesling Trocken to arrive. It’s a non-Grosses Gewächs (GG) classified though Grosses Gewächs-level wine from one of Germany’s most talented dry Riesling sites. For those familiar with the range of Klaus-Peter Keller’s GG wines, his Kirchspiel is often the most upfront and immediate compared to the rest of his big hitters. The same is true here with Katharina’s two top trocken wines, Kirchspiel and Morstein. Kirchspiel is a great vineyard and screams its grand cru quality (Grosses Gewächs) upon opening. Shaped like an amphitheater facing toward the Rhine River, which is roughly five miles away by air, its southeastern exposure has an average of around a thirty percent gradient, with bedrock and topsoil composed of clay marls, limestone, and loess. It’s a warmer site than Morstein because of its lower altitude (between 140m-180m), and the small topographical feature of the curved hillside helps shelter the vines from the cold westerly winds. Katharina has three different parcels in this large vineyard with reasonably good separation, giving the resulting wines a broader range of complexity and greater balance. After opening, the wine lasts for days with a constant evolution that develops more and more layers over a three-day period (if you can let it last that long). It seems relentless, the way a great Riesling should be! We will never have enough of this wine to satisfy everyone, but we will do our best. There are also micro quantities of the single-crus, Benn and Morstein, but both are in extremely limited quantities. However, next year we will have more of those two wines to satisfy the need!

Most growers in the northern hemisphere have finished pruning by now. There are exceptions, of course, with those who test the limits of late pruning before bud break in hopes of a later start to the vegetative cycle. This increases the chance of avoiding frost while potentially extending the vine’s growing season to pass the peak of summer heat and into a gradual cooling of autumnal weather—sometimes just two or three extra days can make a difference of a degree or two of alcohol, and slightly more balanced phenolics. Late pruning is mostly a theoretical practice and doesn’t always yield the desired result at the end of the year, but it seems to delay the start of the season. Here, in Northern Portugal and Galicia, just up the freeway from us, bud break began weeks ago with some varieties.

So far, it’s a strange year (what’s new?) with a big scare early on due to extremely dry weather in Europe. At the beginning of last month, I spoke with Tino Colla over in Piedmont’s Langhe wine regions (Barolo, Barbaresco, etc). He said that it was still bone dry over there and the topsoil in their vineyards was simply mounds of fine dust, which will lead to a lot of erosion when the rains finally arrive.

In northern Portugal and Galicia, some reservoirs have nearly dried up, an unusual and almost unimaginable occurrence in a place that usually has a lot of annual rainfall. Just as the panic set in across Green Spain and Northern Portugal, a deluge arrived and reset the course of the season, ameliorating the stress levels of the local growers, farmers and ranchers. They still need more water, but it appears to be on the way. It’s strange to think that where we are in the north of Portugal will probably closely resemble the climate of Lisbon in thirty years, or sooner.

In February, my wife and I followed the Lima River from Spain (Río Limia, in Galego) back home to Ponte de Lima, passing through the elevated countryside just before the start of the Peneda-Gerês National Park. Things began to take on an eerie apocalyptic feel. The sky was hazy and gray with the platinum shine of an indistinguishable sun straining to break through the thick web-like covering of clouds. We stopped for a little roadside break above a drying reservoir and in the distance saw that Aceredo, a Galician ghost village that had been submerged under a reservoir that was dammed up in 1992, had reappeared. (Two days later, there was a big story about it on the news.) Thanks to the recent drought, the entirety of the ruins emerged from the depths of the then shallow body of water, with recently dried crusts of concentric rings encircling it. Along the steep edges of the reservoir and on terraces were what looked like gnarled tombstones on hillsides but were actually vine stubs whose last harvest was three decades ago. Of course, being the sentimental wine lover that I am, my first thoughts were how tragic it was that I would never know the taste of the wines those vines produced, that the history and the future of the terroir is gone forever.

It’s around mid March as I write this in a hotel room in the center of Ourense, a small, former Roman settlement, famous for its thermal hot springs, which separate the Galician wine regions, Ribeira Sacra and Ribeiro. I was taking a moment after having just passed through Ribeira Sacra’s Sil River gorge with one of our producers, Pablo Soldavini, the winemaker at Saíñas, a bodega in Ribeira Sacra’s Riberas do Miño subregion. The forecast for the day of our journey was purely clear blue skies with a ten-degree (F) spike from the day before, but what we all woke up to was an air thick and dirty brown with an orange tint. It was a dust storm brought in all the way from the Sahara Desert that blew fiercely into southern Iberia and other parts of Europe, dropping orange/brown rain filled with clay particles in some parts of Spain. I was skeptical as Pablo explained the reason for the truly eerie and strange sky, until I checked a few news sources and they confirmed the tale.

After a slightly harrowing start, the road became bumpy but wide enough and far enough from the edge for me to loosen what had up until that point been a Kung Fu grip on the handle above my window. We were on the south hill, opposite the picturesque cliff-side vineyards in Amandi, Ribeira Sacra’s most famous subregion, with the Sil River (really a reservoir now because of the dam further downstream) sitting still below us. On the principal aspects of the south side are north, west and east faces, all officially part of Ribeira Sacra’s Riberas do Sil subregion and curiously, vineyards no longer exist on most of its slopes. We suspected that it may have to do with the easier access of the other side to the northern towns of Galicia, but that surely they will be good spots for future investment, considering the imminent scorching of the other side of the river due to climate change. The hillsides are completely covered in beautiful, dark forest, with a thick covering of oaks and naked, leafless, gray trees poking out from the thick bramble, waiting for their new foliage to emerge in the coming weeks. The hillsides would seem untouched by humans if it weren’t for the many nearly hidden rock terraces tucked inside the forest, abandoned generations ago during the vineyard pandemics, dictatorships, wars (and their aftermath), etc, of the first half of the twentieth century. As we drove along the recently reawakened road that meanders along a hillside made of a variety of metamorphic rocks, we were surrounded by at least a dozen kilometers of hillside running east to west, with a range of about four hundred meters of altitude (1300 feet) from hilltop to the Sil far below, with countless more hills in the distance. The scale of it all is hard to convey in words, another wonder of the world, especially when you’re in it.

The vinous history of Galicia and Northern Portugal is a dreamland for terroirists with a knack for Indiana Jones-style fantasy, but instead of golden statues and legendary things that possess supernatural power, it’s the wines from these sacred places we seek. I drift off in thought on how it used to be there and who brought to life what are today ruins, lost vineyards, remnants of ancient granite buildings and completely abandoned and clearly once thriving countryside homesteads. Even the churches are falling apart, and some are actually for sale. It’s overwhelming to imagine the scope of how much they used to produce there, even more, what the wines tasted like so long ago. The thing about Ribeira Sacra and the Sil River gorge that separates Amandi and Ribeiras do Sil is the overall emotional impact when inside of the region. Not just from the wines themselves, but also from the clear signs of a lost time, a lost people with a strong and what seems to have been a fanatical culture to even attempt to continue to work hillsides like those, let alone build them from nothing in such a treacherous landscape.

Over lunch in the middle of nowhere in Ribeira Sacra with Pablo, we crossed paths with a guy named Pepe. He’s either in his late 60s or 70s (hard to tell with winegrowers sometimes because they often look older than they are from their toils in the sun and vines), and he owns some land in the steep areas of Ribeira Sacra. After lunch, on our sometimes white-knuckle drive on the edge of cliffs in the Sil gorge, Pablo recounted to me some of Pepe’s stories about when he was a teenager, packing grapes out of the river gorge on a donkey. Pepe said he could make only one trip each day with as much as the beast could handle. But how much weight could they actually carry? Apparently a lot, and it occurred to me that that’s probably where the phrase, “an ass-load” comes from. His story seemed like something from ancient times, but he’s still getting around just fine and making time to regularly shoot the breeze and drink beer and wine at lunch time with his buddies. The people of Ribeira Sacra were not born into the same posh culture as those of Bordeaux or Burgundy. The people there were dirt poor for many generations and are only now making a few bucks with wines, a similar story to Piedmont’s Langhe, sixty or seventy years ago. It surely was a hard life that paid little to nothing, with commensurately impoverished living conditions. It’s these kinds of stories that energize my motivation and give greater meaning to my work as an importer. I want to not only bet on our industry’s most recognized champions, but also to fight for history’s underdogs.

Extraordinary terraces are hidden under nature’s impressive return everywhere in these parts, even along the Lima River where my wife and I walk on the river path on weekends and come upon countless abandoned terraces (presumably former vineyards) peeking through the greenery. I think the local Galician winegrowers (more so than the northern Portuguese, who always seem to be just a few years behind Galicia) have visions of rebuilding on their region’s past glories, similar to what’s happening in Piedmont’s Alto Piemonte wine areas (Ghemme, Lessona, Gattinara, Boca, Bramaterra, etc.). None of the Galicians I know have ever been to Alto Piemonte, but they have so much in common with their recent histories and even many aspects of their terroirs. The task is incredibly immense, and today, almost impossible because of the labor shortage: if you don’t own it and it’s not your dream, why would you want to work on these treacherous hills where one wrong move could lead to calamitous injury or even death? The massive financial investment needed and the quickly changing climate seem to make it a fool’s errand. Perhaps… But with a world distressed in so many ways at this moment, we continue to move forward.