Last month we introduced some new producers, including the young Tuscan winegrower specializing in single-site Sangioveses and compelling experimental white wines, Giacomo Baraldo, followed by Forteresse de Berrye, a Saumur producer who bought a historical domaine (former military base) with a decorated vinous history who converted it to organic and now biodynamic culture, and finally, one of Portugal’s most promising talents, Luis Candido da Silva, who crafts a set of unique and gorgeously refined wines in the Douro with his father’s family estate, Quinta da Carolina.

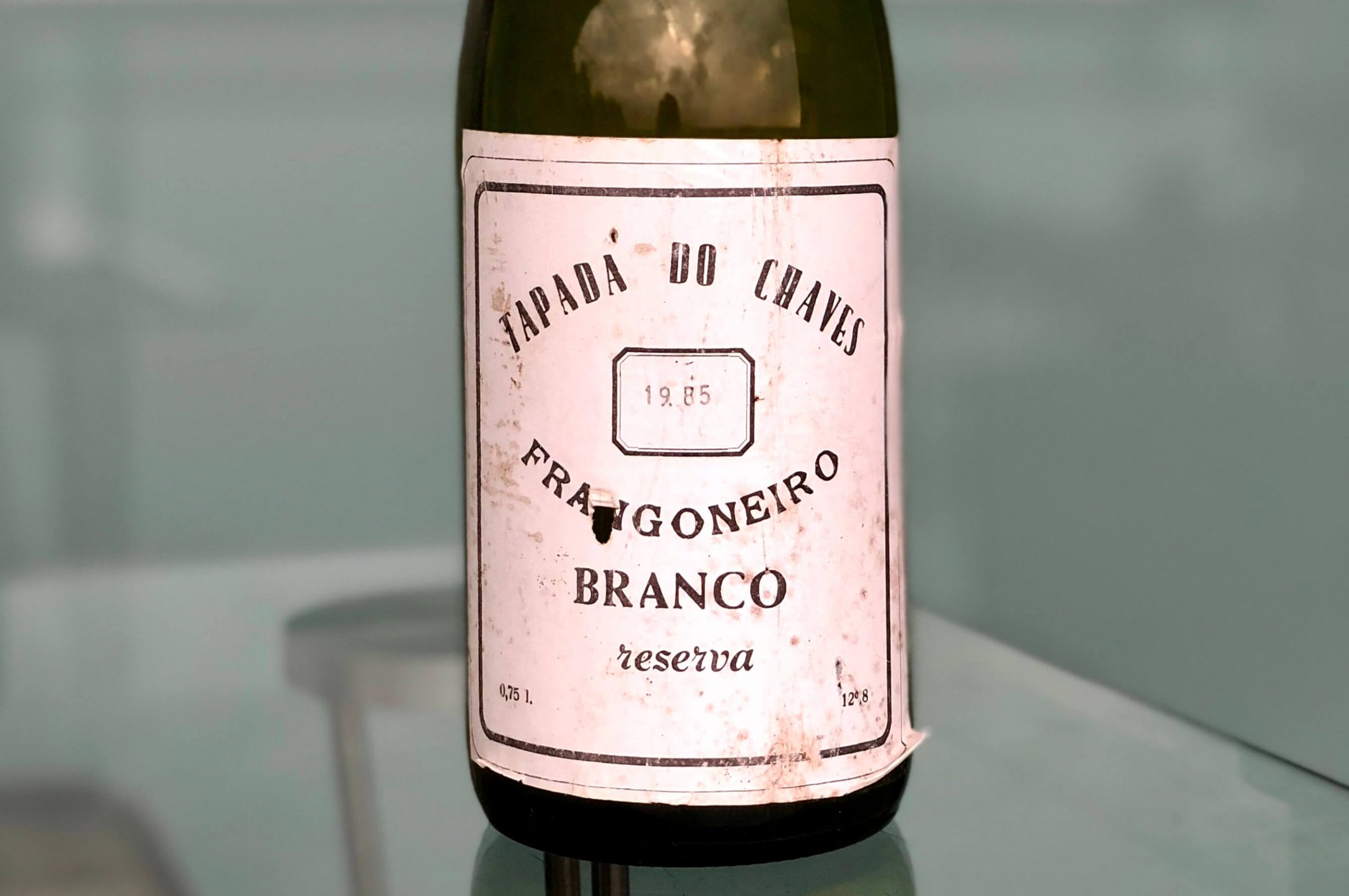

Now we have three more newbies represented exclusively in the US by The Source slated to be introduced this month, including wine coming from a historical Alentejo winery undergoing a complete renaissance, Tapada do Chaves. Often described by Portuguese winegrowers as one of the country’s most “mythical” producers of old wines; if you’re lucky enough to taste one from before the mid-1990s, it may surpass all your expectations for aged Portuguese white and red wines. Two more new arrivals are coming in from good friends in the Loire Valley’s Montlouis-sur-Loire appellation whose organic wines offer a beautiful juxtaposition of this underrated appellation where only the right minds are able to crack its code. Vincent Bergeron crafts ethereal wines, both Chenin Blanc and Pinot Noir, while Hervé Grenier, from Vallée Moray, produces Chenin Blanc of deep, controlled power, and a very limited supply of red wines from Gamay, Pinot Noir and Côt.

Next week we’ll put on more sit-down trade tasting events showcasing wines that are already allocated, some that have limited quantities, as well as those from new producers. Please ask your salesperson to book your seat as they will be limited. We plan to schedule quarterly tastings because there’s so much to show and because we’ve had a great response to them. On the billing: Wechsler’s 2020 Riesling crus, Veyder-Malberg’s 2021 Rieslings and Grüner Veltliners, 2020 Artuke Rioja single-site wines, 2020 Collet Chablis grand crus, and some of our new producers, Vallée Moray (Montlouis), Vincent Bergeron (Montlouis), Tapada do Chaves (Alentejo), and José Gil (Rioja). I’ll be in attendance for each of these events, so I hope to see you there.

February 7th: San Francisco at DecantSF from 11am – 3pm

February 8th: West Hollywood at Terroni from 11am – 3pm

February 9th: San Diego at Vino Carta from 11am – 2pm

February 13th: Moss Landing (Monterey) at The Power Plant from 1pm – 4pm

At the end of the month, Katharina Wechsler will be making the rounds in California showcasing her top Rieslings.

A few 2021s from Tegernseerhof have arrived. As mentioned last month in the short on Veyder-Malberg’s 2021 releases, this vintage is truly one of the greats where everything on all levels of Grüner Veltliner and Riesling are absolutely top tier: full-on in complexity and range, but light on their feet—a perfect balance. Arriving is the 2021 Grüner Veltliner Federspiel “Durnstein,” a collection of different vineyards around Loiben, principally from Frauenweingarten, the former name of this bottling. Also are the big hits, 2021 Bergdistel Smaragd Grüner Veltliner and 2021 Berdistel Smaragd Riesling. These two wines are a blend of the many different micro-parcels they own, mostly further west of Loiben and into the central part of the Wachau, Weissenkirchen. They’re both showoffs, youthful, and energetic, complex but juicy and delicious. 2021 is the year, so grab what you can and know they’ll age as beautifully as how well they’re drinking young.

Fuentes del Silencio’s new releases of the 2019 Las Jaras and 2019 Las Quintas are two wines we’ve been waiting a long time to arrive. 2019 was a special year and showcases the depth of talent in these ancient vineyards revitalized by Miguel Ángel Alonso and his team of passionate winegrowers. Miguel and María, his wife, are doctors (with María still an active surgeon) who set out to bring back the history of Miguel’s birthplace at the east end of Iberia’s Galician Massif. The altitude is high, with the vineyards starting at 800m and Las Quintas reaching above 1000m. This is believed to be the original location for Mencía in its most natural setting, where there’s no need for the acidification that’s done in most other regions that grow this grape prone to lose its acidity in too warm a climate with little temperature extremes. Here, in Jamuz, the harvest is late, usually in mid-October, and the wines speak of this place with its slate-derived soils, the occasional slate outcropping, wild lavender and thyme bushes growing everywhere in this high desert setting, as well as the many pre-phylloxera vines dug deep into the soil that they’re nursing back to health. They started the project in 2014 and now with the 2019s, the sixth harvest under their belt, the wines are finding the extra gears that were clearly imminent with their organic approach in the vineyard and cellar.

Arribas Wine Company has a few new (but late) arrivals. From their stockpile of extraordinary old vines scattered throughout Portugal’s Trás-os-Montes wine region on the border of Spain to the northeast and Douro to the southwest, they have some of the greatest bargain wines in the entire world. Imagine these ancient terroirs along the Douro/Duero River grown on gnarly slopes and rocks identical to those of Côte-Rôtie and Cornas, though they go for only a fifth of the price for even the cheapest of these French appellations. That’s what you get, but with over forty different varietals blended into some wines, and 10.5-12% alcohol… It all seems like a dream, but it’s as real as it gets. Arriving are the 2021 Saroto Branco and 2021 Saroto Rosé.

“The 2021 growing season was nearly perfect as we witnessed very moderate conditions during maturation. In fact, because summer was not hot and nights were unusually cold, maturation was slow and gradual, contributing to excellent acidity in the wines. The grapes for the Saroto White 2021 (which is really like an orange wine) were harvest by hand on September 8th and were foot-trodden in a traditional lagar, totaling three days of skin maceration.” They were then aged in old French oak barrels for seven months. The vine age for this blend of different white varieties comes from 51-year-old vines on granite and clay at 650-700m. The 2021 Saroto Rosé is unfortunately in very low quantities. It comes from a blend of 50% white and 50% red varieties, mostly from the same vineyards as the white and drinks more like an extremely light red, like a Spanish Clarete—a wine somewhere between rosé and red without stinging acidity while being refreshing and in the full red-fruit spectrum.

I’ve had my eye on Tapado do Chaves for a few years prior to signing with them. We were introduced to the wines by one of my great friends and winegrowers in Portugal, Constantino Ramos. When asked about what old wines in Portugal I should get to know his first suggestion was Tapada do Chaves. Constantino helped find some old wines from the 1980s and early 1990s that were being sold by a Portuguese retailer, and my first experience with them was shocking. Though more famous for their historic red wines, the whites were just as good. Everything aged well, even though the bottles looked like they’d been on top of some Portuguese guy’s countryside fireplace for a couple decades and had low fills and corks barely clinging to the insides of the bottles. I bought another mixed three cases of old wines and shared them with friends from Galicia. Soon, the source of the old bottles dried up but I was convinced that I should investigate, even though I was told the most recent wines were not the same. It was true that they weren’t, but a visit to the vineyards showed what was coming.

Tapada do Chaves’s legacy in Portugal’s Alentejo is legendary, though there were many speed bumps along the way, such as the Portuguese dictatorship (1933-1974) and the sale of the estate in the late 1990s to a sparkling wine company that faltered on quality of the Tapada do Chaves wines for decades. In 2017, with the purchase by Fundação Eugénio de Almeida, led by one of Portugal’s most celebrated oenologists, Pedro Baptista (known for the highly coveted Pera Manca wines), it began to regain its footing. Biodynamic farming was immediately incorporated on this unique granite massif on the side of Serra de São Mamade, which towers over the flatter lands more typical of the Alentejo. The whites grown in vineyards planted in 1903 and massale selections replanted some forty years ago are a blend of Arinto, Assario, Fernão Pires, Tamarez and Roupeiro (among others), and fermented and aged in stainless steel and old French oak barrels. The reds, from vines planted by Senhor Chaves in 1901 are a blend of Trincadeira, Grand Noir, Aragonez and Alicante Bouschet. All are aged in older French oak barrels, then bottled and released around seven years after the vintage date.

Today, Tapada do Chaves is selling their new releases of white wines from when they first took over, but the reds still have some years to go before the change of direction into biodynamic culture and a fresh new take from Pedro Baptista. During a meeting with Pedro, he told me of the history of the winery and about how, when he was a little boy, his father used to take him to Tapada do Chaves to collect their yearly allocation. Though he’s new to Tapada do Chaves, it’s not new to him. This famous estate weathered the dictatorship and continued to work independently while few in Alentejo (and all of Portugal) did.

Portuguese white wines may be the most underrated white wines in the world. Since moving to Portugal in 2019, I’ve had many examples of aged white and red wines for such a low price that have truly been astonishing, though the most interesting for me have been the whites. Tapada do Chaves is no exception. The old whites that didn’t fail due to bad corks were incredibly good—fresh, slightly honeyed, minty and medicinally herbal, salty, deeply textured like a very old Loire Valley Sancerre without the varietal nuances of Sauvignon Blanc.

My first interaction with the 2018 Tapada do Chaves Branco was extremely encouraging. In a blind tasting with some other trade professionals along with some other wine samples from Portugal, it stole the show. It stands as another strong example of the talent of Portuguese white wines made from a blend of many grapes. Despite the wide variety of fruit, the terroir elements are always there, along with the high quality of the replanted vines from massale selections taken from the unique biotypes grown inside of Tapada do Chaves’ walled and gently sloping vineyard on granite rock atop the massif. After the tasting, I put what was left in the refrigerator for more than a month, uncorked. I forgot about it after tasting it once the day after the first tasting. Then I started to taste it again over the coming weeks to check in, a little here and a little there; it was bulletproof. I remain shocked at the resilience of this wine and its inability to be fatigued. Based on this and my experiences with the old wines from this estate, I believe that it has the potential to age very well—not only to be sustained, but to improve tremendously over time as so many Portuguese white wines do.

The 2018 Tapada do Chaves Branco Vinhas Velhas comes from the ungrafted 120-year-old vines first planted by Senhor Chaves in 1901. This wine is profound but will greatly benefit from time in the cellar—a long time. It carries many similarities to the first white in the range, except that it’s denser and more concentrated. One could simply retaste this wine for a month and add, brick by brick, a new tasting note with each soft turn of its evolution. To drink it quickly would be to miss witnessing its splendor. There are few cases imported because there are few made from these historic, nationally-treasured vines. It is indeed a little expensive, but in twenty or thirty years you’ll be happy to have captured a few bottles to share with your kids or grandkids.

Timid and cautious yet gently charismatic, middle-aged (born in ‘78) but youthful and spirited, with a heart of gold and a deft touch with his craft, the gracious Vincent Bergeron discovered his calling to the vigneron life while walking the streets for la poste, trading in antiquities, and periodically working construction. These were simple trades, though perfect for young ponderers like Vincent, at least for the moment.

He received degrees in Art History, Literature, and Agriculture, had many different work experiences that were capped by the viticultural mentorship of Jean-Daniel Kloeckle, Hervé Villemade, and Frantz Saumon. The latter gifted him with a tractor, a small Pinot Noir vineyard and part-time cellar job, and Vincent commercialized his first wine in 2016 (though he’d tinkered with various bottlings since 2013)—500 bottles of bubbles that all went to a Japanese importer. When he talks about his project, he always starts with his great appreciation for Frantz’s generosity, the man who gave him such a jumpstart.

He and I were introduced by Montlouis-sur-Loire local, Gauthier Mazet, also a new vigneron (practicing since 2020) and wine industry connector, who lives by the river in the epicenter of Montlouis’ bloom of amazing producers. They’re all making deeply inspiring wines from an underdog appellation in minuscule quantities, most of whom sell almost everything to Japan and very little in France. This includes Vincent Bergeron, as well as two others who’ve also trusted us to be their US importing partner: Hervé Grenier, owner of Domaine Vallée Moray, a craftsman of densely mineral and emotional wines that embody the focus of a scientist maker in his second career as a vigneron, and Nicolas Renard, a forcefully independent and elusive natural wine wizard, a virtual ghost whose wines are nearly impossible to acquire. He transcends style and mode with no-sulfur wines, both white and red, that are simply in their own stratosphere, easily holding court with the best examples of x-factor-filled, dense, moving whites in the world, and reds that captures the essence of the earth and human in a bottle.

I first saw Vincent on a cool and sunny spring morning in one of his vineyard parcels close to downtown Montlouis. With his thick mane of lightly salted pepper flowing in every direction, he wore casual well-worn clothes stained by hard work, and he shied away from the camera as I stole a few shots before our official greeting. His hands are those of a true vigneron; they were strong from a life of labor, dirty from the vines and caked with earth, swollen, scratched, scraped, gouged and bloodied. He seemed a little self-conscious to be shaking my hand, and I instantly knew I’d like him: it was impossible not to.

Vincent is rare in today’s world of self-aggrandizing young vigneron talents—sometimes appointed by the wine community and often by the self, as “rock stars.” Many of them seek celebrity and membership in idealist tribes rather than going for truth and an honest view into this métier, this art, and above all, this craft, a marriage of homosapiens and nature. Vincent is a vigneron’s vigneron, a human’s human, an uncontrived example of how to live and simply let be, spiritually, without trying to be “someone.” He only tries in earnest to be himself—not for the world to see and celebrate, but for his family, his comrades, for himself and his humble yet idealistic relationship to wine and connection to nature. Though not an active provocateur, to simply be in his presence you might, like I do, contemplate life choices and motivations, what’s important to you and why it’s important, along with, “What the hell am I doing with my few short years on this planet?” Without effort or intent, he enriches others with his homage to his environment, a spirituality and open self-reflection in casual settings, drinking wine outside on a cold and sunny day in front of a tiny, wobbly table packed with cheeses, cured meats and oysters (also a favorite of his extremely young kids—only the French…), a perfect match for his bubbles and white wine. The talks are fresh and lively, more about life than wine, though in this context wine is life. His wines speak for themselves, and gently, as do his organic and biodynamic vineyards that are teeming with life. Sometimes he appears lost, even surrounded by his people, as he gazes into the world, into nothing, thinking, reflecting, wondering about his path. Perhaps he’s thinking less than it appears that he is, but it’s doubtful.

Emotionally piercing, Vincent’s mineral-spring, salty-tear, petrichor-scented Chenin wines flutter and revitalize; a baptism of stardust in his bubbles and stills—a little Bowie, a lot of Bach. His Pinot Noir is earthen en bouche, and aromatically atmospheric, bursting with a fire of bright, forest-foraged berries and wild flowers, and cool, savory herbs rarely found in today’s often overworked, oak-soaked, and now sun-punished Pinot Noirs, the wines that were the heroes of the past millennium, but today are a flower wilting under the relentless sun. Advances in the spiritual heartland of Pinot Noir have been made, though I sure miss the flavors of the Côte d’Or from my earlier years among wine.

Vintage is important with Vincent’s wines. With his concession to nature and commitment to honor the season, sans maquillage, ni compromise, he sets his wines on a direct course, showcasing each season’s gifts and its challenges, allowing his wines to freely express the mark of their birth year. Warm vintages (2020) taste of a season’s richer fruits and a softer palate while still being delicate and complex. Cold years (such as 2021) are brighter, fresher, more tense and rapier sharp with a gentle and welcome stab.

The Vineyards

On the east side of the fabulous but small and modern Loire city, Tours, across the Loire River from the historic splendor of Vouvray on a series of undulating hills with some dramatic slopes mixed with mellower hilltops, sits Montlouis. It’s a long stretch of vineyards between the rivers Loire and Cher to the south, on floodplains shaped by torrential flows over the eons.

Vincent explains that between Vouvray and Montlouis there have always been differences in soil structure, topography, and social hierarchy. While Vouvray maintains a more celebrated vinous history (as illustrated by the bougie houses across the river, so different from Montlouis’ more rural and less ornate neighborhoods), some of its historical relevance seems to stifle creativity and growth—as happens so frequently in many historically celebrated regions in the wine world. Why change what already works so well? Furthermore, historic families often prefer to preserve their position instead of rocking the boat of a viticultural system that, after many generations in place, continues to provide wealth for those next in line.

In contrast to Vouvray, Montlouis-sur-Loire is filled with young and finely aged winegrowers with open minds and a strong desire and capacity for kinship and the sharing of ideas. Many had widely varied experiences prior to choosing the vigneron life and together they’ve created a tribal environment where they help each other to push that rock further up the hill. Organics have become a way of life for many in this circle and the influence of this free-thinking community is expanding. Montlouis is exciting and there are so many talents emerging from this extremely praise-worthy appellation that’s up to now been an underdog. Always the bridesmaid and never the bride? No longer. Some earlier trailblazers opened the path, the most famous, perhaps Jacky Blot and François Chidaine, and others more quietly developing their names and furthering the reputation of the appellation, like Frantz Saumon, Thomas Lagelle, Julien Prevel, Ludovic Chansson and Hervé Grenier, all of whom Vincent admires and calls friends.

Montlouis is mentioned in every wine book as being sandier in general than Vouvray, which is true, though there’s often great depth of clay (lighter on average than Vouvray’s) further below the surface of the topsoil, before the roots intersect with the famous whitish/yellow limestone bedrock of much of the Loire Valley’s best Chenin Blanc areas, and a slew of other elemental contributors have a say in the wine’s subtleties. Vincent has various plots in a few different zones of Montlouis, close to the bluffs that overlook the Loire River and others further away and closer to the Cher, both on classic limestone bedrock, with variations of perruche (fossils, lithified clay, flint/silex), sandstone, clay, and limestone. These structures are not independent of others but rather form a conglomeration and vary from one to the next and within the plots as well. To see the diversity, go to eterroir-techniloire.com

Though the land was already worked organically prior to Vincent’s last fifteen years of ownership, it was certified as such in 2018, and biodynamic principles are practiced during the season’s life cycle, though they’re not followed closely in the cellar. Plowing is done mostly by horse every third year, or by Egretier plow, a fitting pulled by tractor. The harvest begins with alcoholic and phenolic maturity in line with the chemistry of the grapes—pH, TA—and of course, the taste of the grapes. Pinot Noir is the first to be picked, followed by Chenin Blanc for sparkling, then the still Chenin.

The Wines

Vincent’s bubbles, Certains l’aiment Sec “Vin de France,” is gloriously ethereal and fun to drink. Like all his wines, the vintage has a big voice in the overall expression, though the spirit is the same: serious but playful and easy to gulp down. It’s made with a simple method using early pickings from the Chenin Blanc parcels. (Here, in this part of the Loire Valley’s Chenin Blanc region, many growers make numerous picks on their vineyards rather than just the one—a smart and utilitarian method to maximize quality with what yield nature provides, without being too forced.) Spontaneous fermentation takes place in fiberglass vats. Following malolactic fermentation, the wines are hit with their first sulfite addition of 20mg/L for its eighteen-month bottle aging. No fining, filtration, or dosage.

“Morning, Noon and Night,” is a perfect name for this exquisite, fine, platinum-hued wine labeled Matin Midi et Soir – Chenin Blanc “Vin de France.” This is Vincent’s inspiring still white wine, (especially the 2021), where the vintage seems tailored for his style: helium-lifted, minerally charged, cold, wet rock and taut yet delicate white fruit. All the elements from each vineyard parcel in his 3.4-hectare stable of 40-plus year-old massale selections (and .60ha of clonal selections) give it breadth and complexity while maintaining Vincent’s head-in-the-clouds Chenin Blanc. It’s hard to pick a favorite in the lineup, but this low sulfite dose Chenin (30mg/L) raised twelve months in oak barrels (with some new to replace older barrels, which aren’t noticeable) is truly singular for this variety in the Loire Valley, so much so that it doesn’t even seem to be of this earth, but rather plucked from the heavens, pure, untainted, downright angelic.

The first taste of Pinot Noir out of the barrel, Un Rouge Chez Les Blancs, was jaw-dropping, a burlesque walk from glass to nose and mouth. In recent years, I’ve greatly missed Pinot Noirs that carry this grape’s nobility and naturally bright, energetic, straight flush (hearts and diamonds) of red fruits and healthy forest with wet underbrush. I was tempted to be impolite and drink down my entire barrel sample from this mere one acre of vines (0.4ha) instead of returning it (2021 vintage) to whence it came; I could’ve nursed that first 500-liter barrel to completion. By the end of my first visit, I wanted everything in his cellar just so my friends back home could bear witness to it. Given to him—yes, given—by Frantz Saumon, the land was organically farmed long before Vincent took the reins of the plow horse. Optimal for this young vinous artist to explore his direction with epic, terroir-precise and living fruit, he nailed it. It’s true Pinot Noir perfection: egoless, a balance of nature and nurture, sensual, honest, captivating, pristine, delicious. There’s no sulfite added to this wine, so the future of each bottle will be in the hands of the handler, though with its naturally low pH, high acidity, and low alcohol, and, most importantly, its balance, it should manage well over time. One pump-over per day in the beginning, two later on in the fermentation, a year aged in 75% old oak barrel, 25% in fiberglass tank, and it’s not fined or filtered. The 2020, tasted blind by our staff in January, blew them away—an Allemand-like Pinot Noir. There’s not enough of the 2020 to go around, so we’ll have to wait for the taut, red-fruited 2021 to come!

Endless curiosity and self-reflection are characteristics of the most compelling vignerons. Some are born into the métier, many of whom are children of the greats, and a select few reach for new heights never before attained in the family line. Then there are the industry’s most enlightened freethinkers who come from the outside, drawn in by revelation, romance, and occasionally, a healthy mid-life crisis. At forty-six, Hervé Grenier abandoned the life of a scientist and began anew when, in 2014, he had an epiphany that brought him to an old ramshackle cellar with beautiful, healthy, organically farmed vineyards, in the quiet countryside of the Loire Valley appellation, Montlouis-sur-Loire.

Hervé explained, “During a visit with a winemaker I used to frequent, I suddenly thought, ‘I’d like to do that!’” Inspired by the excitement of a significant life change, Hervé left a career in academic meteorology research and underwriting, focused on agricultural climate risk in the States, then moved back to France with his American wife, Emmy. They started their new adventure, only a couple of solid golf swings away from and to the south of the Loire River, on the first significant left-bank alluvial terrace that runs in parallel to them, but 30-35m above the river. Over time they bought more parcels further south and closer to the river, Cher, as they reshaped and converted the land to organic farming. As of 2023, they maintain roughly 4.5 hectares, 3.2 of which are Chenin Blanc with an average of 60-70 years of age, a single hectare of Pinot Noir, and 30 ares (.75 acres) of Gamay.

Tasting with Hervé in his long, dark, damp, and cold underground concrete tunnel lined with mold and wine-stained old French oak barrels, is thrilling. Impressive from the first sample, Hervé shares his perception of each wine’s strength and weakness observed through its journey from budbreak, to grape, to wine. Organoleptic vibrational overload builds with each thieved sip, sips that gush with vinous lifeblood along with the gifts extracted from unique soils that have been bolstered by the microflora and microfauna and minerals mined from the rock and soil. His dry Chenin Blanc wines are vinous with the sweet green chlorophyll captured from the sun, the alchemy of slow fermentation—very slow, never forced—and the stamp of healthy lees from happy plants that render his wines digestible and revitalizing. The truth-seeking Hervé seems in deep reflection with each taste, contemplating the wine, his own nature, his choices. Vacillations between bursts of joyous laughter and doubt and self-reflection are interrupted when he hits the mark. Inspired and utterly serious, he slowly chants, “Ça c’est bon. Ça c’est bon. Ça c’est bon.”

On Terroir

Montlouis has a different quality of soils from those of Vouvray, across the Loire River. Vouvray vine roots typically have closer contact with tuffeau limestone bedrock and more clay in the topsoil than most of vineyards in Montlouis-sur-Loire. Hervé believes that the wines on this side of the Loire River are typically less marked by minerality than Vouvray, he says, “So there’s room for other stuff!” The composition of Montlouis-sur-Loire soils from a general point of view (though each site is different) is a mix of perruches (fossils, lithified clay, flint/silex), sand, and clay, atop bedrock of tuffeau limestone with varying levels of topsoil depth. ‘Montlouis is sandier than Vouvray,’ is the usual summary in textbooks, but this depends on each parcel, because it’s much more complicated than that.

With a manifesto (adopted by artists like him) that espouses ‘terroir expression over all things,’ Hervé says, “I would not like that my wines mainly express terroir, even if it’s a beautiful terroir.” But what is interesting and even slightly contradictory to Hervé’s notion of Vouvray and Montlouis and the terroir influence is that his wines are wrought with a sense of place; perhaps not only in the perception of mineral nuance, texture, structure, and ripeness imposed by the site’s soils, exposure and grape, but his full commitment to the preservation of his full-of-life, organically farmed old vines, the quality of the soils, and, of course, his skill in capturing their essence. His whites are strongly mineral in impression, thickly textured and weighted on the palate and the nose; his Aubépin Chenin Blanc is like a magnum squashed into a half bottle. Early on in his newfound life as a vigneron he demonstrated (through his 2017 and 2018 Aubépin, the fourth and fifth vintages of his life) a precocious and keen understanding, maybe even a certain level of mastery, in his sculpting of wines with clean and fine reductive elements—no doubt an intended consequence of protecting and preserving his sulfite-free, naked wines until bottling. The body is fuller though the wines remain finely balanced between the earth and the sky. The deep clay underneath the sandy topsoils, the quality of farming and his personal calibration of fruit maturity is marked through his entire line of wines. Terroir aside, Hervé’s wines reflect his intuition, curiosity, and measured hand.

White Wines (and Orange)

Hervé says he wants his wines to deliver, “The quality of the raw material produced from my vineyards; that they should feel good when you drink them. Satisfying. Pleasurable.” And he goes well beyond his aim. The Chenin Blanc are spectacular, singular, emotional, honest, and heavy on x-factor. For this taster, they stand tall among everything from the Loire Valley; sometimes they even tower over well-known and celebrated wines overwrought by cellar technique and experimentation. Hervé’s simple and confident approach is to let his wines find their own way, which they do. His objective for them to “be satisfying and pleasurable” is easily achieved, even for the everyday drinker. One doesn’t need to be an expert, or a wine lover with a penchant for the esoteric to fall for them, though a wine insider may be needed to help people find a bottle. They’re also profound, brainy, finely etched, and swoon-worthy for wine experts in search of a new frontrunner in the world of natural wine. Though they indeed fall into this genre, they are sterling examples of sulfite-free reds and whites, void of fault and without explanation or excuses. The whites don’t usually have any sulfur added at any point of the process, though if a wine is in peril he has no reservations when it comes to giving some assistance. This leaves his wines unclipped, robust and true in expression, free flowing yet harnessed and directed.

Hervé describes his approach in the cellar as “The simplest and most natural way to make wine. The only intervention is the topping up of the barrels until I prepare them for bottling.” Like the superficial tillage of his vineyards (light scraping in Hervé’s case), his winemaking hand is gentle and patient. The fermentation of the classically styled whites, Cailloutis and Aubépine, takes place in old oak barrels with the total lees from the press—no débourbage (wherein the lees are settled before the wine is racked off them). There are no finings and filtrations, nor additions of sulfites—though, as already mentioned, necessary exceptions can be made. Fermentations can last months, or more than a year before dry. The two Chenin Blanc wines are made in the same way, with Cailloutis a blend of many different parcels and Aubépine a specific site of old vines closer to the Cher than the Loire.

Hervé also makes an orange wine from Chenin Blanc (80%) and Sauvignon (20%), called, A Mi Chemin. This wine usually undergoes a two-month maceration on skins (fully destemmed) and is sparingly punched down, pressed, then aged in old oak barrels. Though the Chenin Blanc wines are glorious, Hervé claims with a smile, “A Mi Chemin is my wine.” It’s more gourmand than the other wines, with floating tea notes, dried citrus, stone fruit skin and dried flowers as opposed to fleshy fruit notes—which is to be expected with orange wines. It, like many other orange wines, is a wine for all occasions, with great versatility when it comes to chosen fare.

Red Wines

Hervé’s reds sing a bright and merry aromatic song. They’re fun, and they achieve Hervé’s objective of pleasure-led, feel-good, crunchy reds. Pinot Noirs grown in Montlouis and made by the right grower are a fabulous surprise, as are the Gamay. He doesn’t commit the reds solely to single-varietal bottlings but likes to make blends, too. There is the Pinot-led blend with Gamay, Arcadienne, and the solo Pinot Noir bottling is Les Figurines—neither are imported yet as they are produced in very small quantities. Côt Libri is made entirely of Malbec from very old vines on extremely calcareous soils in Montlouis-sur-Loire. It was fully destemmed and after fermentation ages in 400l-800l old barrels. As expected with this variety, it leads with more purple fruits than red, and after quite a few years of cellar aging in bottle it shows a broad range of earthy, savory qualities.