Climate change is relentless. June was a scorcher in Europe while at the same time just a month ago France was hit by yet more major hailstorms in many areas. European countries are playing a high-stakes game of dodgeball, with the climate playing an unrelenting offense. If it’s not hail, it’s mildew pressure and/or rain at the wrong time, hot winters followed by Jack Frost in the Spring and summertime sharknadoes. Nowhere seems immune, except maybe places producing sun-drenched boozy wines along the Mediterranean coast. Who in the fine wine world wants those, anyway? A lot of people, actually. But like me, perhaps you might be living on the fringe of the wine world, where you don’t want to be punched in the face by the alcohol in a glass of wine, but rather by a nice, fresh, acidic and minerally love tap, or maybe the occasional electrocution by these latter elements. Well, 2022 is off to a good start for many, but so much can happen between now and harvest. Gino Della Porta, from the new Monferrato project in Nizza, Sette, says that the churches in Piemonte fill up with praying vignaioli before harvest and return to emptiness once the grapes are picked. We wish the best of luck to all winegrowers out there, not only those who make our preferred elixirs.

We have two new website features that should (hopefully) add to the joy of perusal. Mobile devices will always fall short of laptops or desktops when it comes to more fluid navigation, so they’re where you will see the biggest improvements. The first redesign is our Producers menu. We’ve customized new country maps with more precise region selections and an easier view of each producer from next to their map without the need for excessive scrolling. The second improvement is a producer profile sidebar on our producer profile pages that displays more related content. The wines are also easier to get to with a quick dropdown (I know the profiles can be long, which required a lot of scrolling to finally reach the wines), as are related materials like terroir maps, videos, newsletters that update information that may not be found on profile pages or wine descriptions, and lastly, the ability to download the profile content into a printable format. Please don’t hesitate to send suggestions directly to me at ted@thesourceimports.com. We’re always looking for ways to improve your experience and much of the time we can’t see obvious things right in front of our faces.

Following the New Arrivals, I’ve posted some highlights to drop you a little tease to get your wheels turning for the future. There are so many spectacular wines to talk about, but I trimmed it down to a select few during my forty-day Europe trip this Spring.

The logjam at ports continues and while some countries are getting better, France remains solidly in last place with improving their turnaround time from the moment we submit orders for a container to the time it arrives at our warehouse. Why France more than anyone else? No idea. We don’t know what will hit for sure in July, but we think this new batch of French wines just might do so.

The last release from Chevreaux-Bournazel stirred up a frenzy the moment we published last year’s June Newsletter. The small amount of wines allocated to us were out of stock by the end of the day—an unexpected result for this quite unknown but likely-to-turn-cult Champagne producer. We have a little more wine with the 2018 vintage than last year, but not much more.

Decanter magazine describes the 2018 vintage as “truly exceptional,” and “destined to be remembered for producing both quality and quantity.” According to Bollinger’s Cellar Master (via drinkmaster.com), Gilles Descôtes, described it as the “best of his life,” and that there is a resemblance to both 2002 and 2004. 2018 is indeed a year with a good yield and also very good quality despite the warmer year. One key was that the bountiful crop helped maintain balance for the wines than a smaller crop would, leaving a greater amount of acidity for the level of ripeness.

Three Pinot Meunier-based wines will arrive from this micro-producer, surely the smallest from any producer in our portfolio other than our Txakoli revolutionary, Alfredo Egia, and a new organic and biodynamic-certified Bordeaux producer, Sadon-Huguet, that will hopefully arrive before the end of the year. Two cuvées imported before are Connigis, grown on a very steep slope (think Mosel-steep) with hard limestone bedrock, and clay and chalk topsoil, and La Capella, grown on an even steeper vineyard (like the steepest, terraceless vineyards in the Mosel) with a thinner layer of clay topsoil, chalk bedrock on the lower portion, and silex (chert), chalk, and marne (calcium carbonate-rich clay topsoil) in the upper section. The new cuvée, Le Bouc, is their first blend of different vintages and the two plots for La Capella and Connigis.

Chevreux-Bournazel’s Champagnes are all biodynamically farmed, unchaptalized, naturally fermented with indigenous yeast, unfiltered, zero dosage, and with all cellar movements made in sync with the rhythm of the lunar calendar. Their range is led by dried herbs and grasses, tea, honey, dried flowers of all sorts from yellow, orange, violet and red, and a multitude of savory nuances. More than anything, I find that Stéphanie and Julien’s wines separate themselves from much of the typical Champagne style due to their strong polycultural setting, different from other more famous Champagne areas. Here, there are large expanses of separation between vineyards in the backcountry of the Vallée de la Marne, and the wines are a notable departure from fruit-led, bony Champagne with fewer layers of greater complexity. Massive forest-capped slopes covered in an endless sea of vines with no other crops in sight than the swathes of grain fields in the flatter areas below don’t lend themselves to such a broad array of nuances. Chevreux-Bournazel’s wines are alive and their forcefully savory nature is almost overwhelming, which makes them gastronomically suitable for a greater mix of cuisines.

The 2020 season was not as hot as 2018 and 2019. While 2019 may have jumped a little further away from being described as “classic” Chablis due to its riper fruit notes (but with a surprisingly high level of acidity for this warm year), some hail 2020 as “classic,” “early but classic,” and “a great vintage.”

I don’t even know what “classic” means anymore with Chablis or anywhere else, do you? I know what “great” means to me, personally (with emotional value topping the list), but my “great” may not be yours. Our current frame of reference and experience sculpts all of our preferences, and formative years are always present too. People who’ve been in the wine business for decades have a different reference for wine than those recently seduced by Dionysus. Classic Chablis? I haven’t had a young Chablis that vibrates with tense citrus and flint, a green hue in color, shimmering acidity, and coarse mineral texture all in the same sip for a long time—so long that I don’t even remember the last vintage I had those sensations with newly bottled Chablis. (Of course, a recently bottled wine still high strung with sulfites can give that appearance but the wine will bear its truer nature a few years after its bottling date.) Chablis is different now. Burgundy is different. Everywhere is different than a decade ago and even more so than two decades ago. With the composition of today’s wine lists and their one or two pages of quickly-changing inventory compared to extensive cellars of restaurant antiquity, most of us developed different expectations—if not a completely different perspective—for wine now than what “classic” used to imply. (The idea of “classic” from more than twenty-five years ago when I first became obsessed with wine now conjures images of chemically farmed vineyards and their spare wines.) 2020 may be fresher and brighter than the last two years in some ways but maybe with less stuffing than the similarly calibrated 2017s, a vintage I loved the second I tasted the first example out of barrel at Domaine Jean Collet. Maybe we can call 2020 “classic,” but if picking started at the end of August would that be “classic” graded on a curve?

Sébastien Christophe’s wines are classic in their own way. Like older-school Chablis, they’re usually in no hurry to reveal their cards upon arrival, especially the top crus and his Chablis Vieilles Vignes. Sometimes they perplexingly arrive with a blank stare, but after a proper rest they liven up; some take a month, some three, others a year or more. The usual exception is one or the other of his two entry-level wines, the Petit Chablis and Chablis. Some years the Chablis comes out slinging miniature oyster shells at your face while the Petit Chablis plays tortoise. Other years, the Petit Chablis springs off the boat with a big smile and sticks you with rapier mineral nuances, blowing away expectations for the appellation with its wider frame and rounder palate than most wines from this appellation. One of them is almost always notably stronger than the other when they arrive, but a year later the script can flip with the same vintage of wines. Let’s see what 2020 bolts from the starting block first.

Between the premier crus and the Christophe starter range is the lonely Chablis Vieilles Vignes—too big to play with other Chablis appellation wines and not part of the premier cru club. Sourced from two parcels in Fontenay-près-Chablis, one above the premier cru lieu-dit, Côte de Fontenay, and the other southeast of the village, they were planted in 1959 by Sébastien’s grandfather. These vines render a richer wine out of the gates that tightens up with more aeration (the opposite of many wines), shedding superficial weight and concentrating power. Minerally and deep, it often rivals one or another of Sébastien’s premier crus from each year. Were these west and north-facing parcels in a more southerly exposition and outside of the small valley they sit, they surely would be classified as premier cru sites.

Similar to the Petit Chablis and Chablis, it’s hard to predict which Premier Crus will show the best out of the gates; it’s anyone’s game upon arrival, no matter the pedigree of the cru. What remains somewhat consistent, at least in my experience, is the way they behave in a general sense. Fourchaume is the most muscular, offering a stiff mineral jab and a stone-cold smile with a set of nice pearly shells. Opposite of Fourchaume, Mont de Milieu is sleek, fluid and versatile, resting more on subtlety than force. It often shows as much left bank nuances with its ethereal minerality and more vertical frame. Montée de Tonnerre borrows from the best of each of the other two premier crus and turns the dial down a touch in pursuit of sublime balance. Usually the most regal, sometimes it takes a while to show its fine trim and breed, while on another day it shows up straight away.

While Montée de Tonnerre takes pole position in Chablis’ super-second premier crus for many Chablis followers, it doesn’t always finish in first place chez Christophe et fils. The title of best premier cru here is up for grabs each vintage and all have the potential to top the podium. Each individual taster’s preference and calibration on balance, and the moment the wine is tasted—influenced by the mood of the taster, the environment, what they ate or are eating, anything they tasted beforehand, the order in which the wines are tasted, the cork, the moon, the barometric pressure, etc—will decide their frontrunner. It’s true that most compelling wines aren’t static, and neither are we. The wine we prefer today may not be what we prefer tomorrow. This makes wine fun but sometimes maddeningly elusive, especially in moments when in pursuit to relive an extraordinary bottle and the follow up is inexplicably off and deflating. With too many variables, firm conclusions based on a single taste or bottle, or moment in time, is shaky ground. The most solid advice in wine is to consistently buy from a producer you love. It’s the most reliable way to keep the average quality of your wines high.

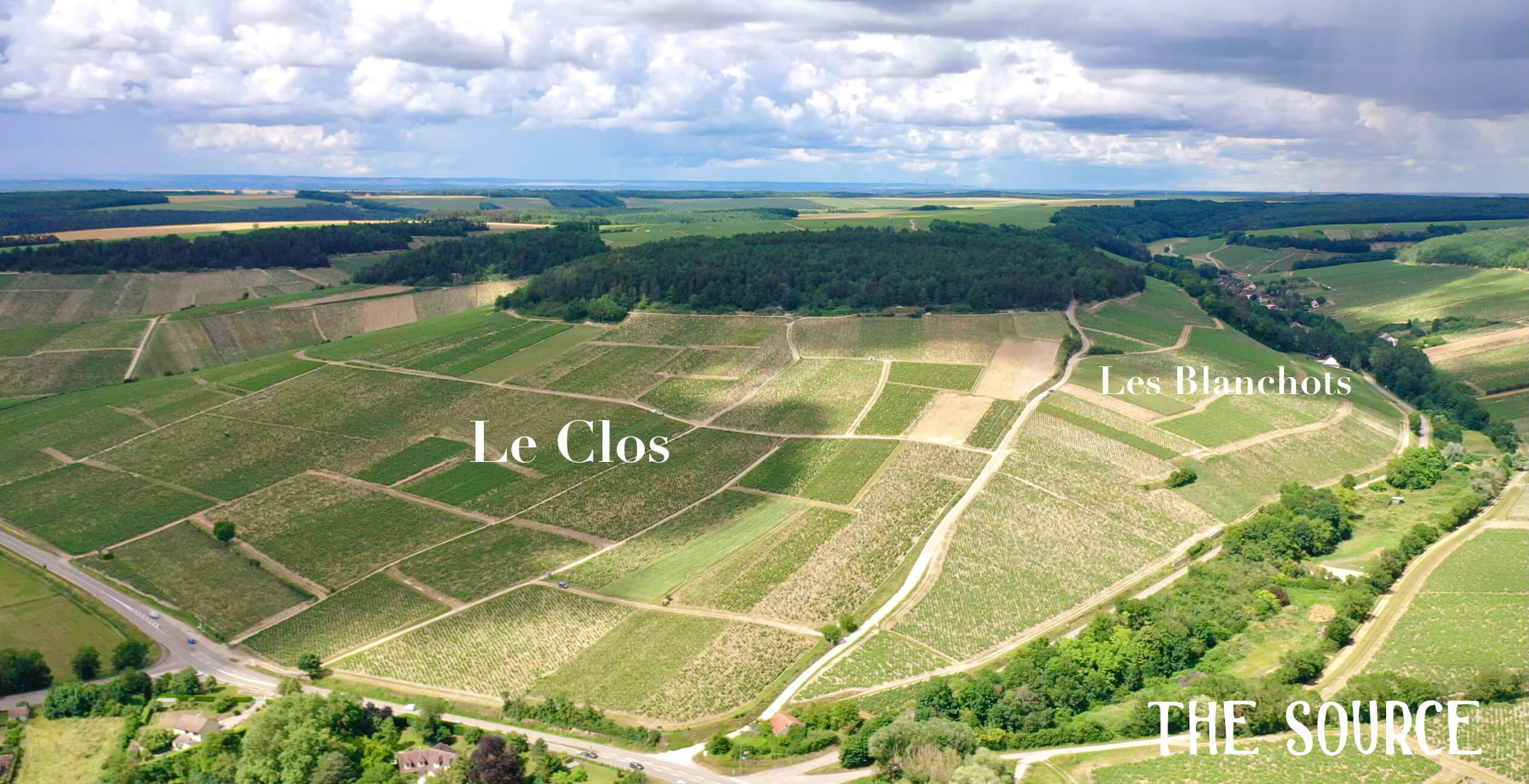

Christophe’s first vintage of Blanchots was 2015. This grand cru faces directly south on a sharply angled, wedge-shaped hillside. Those familiar enough with this grand cru know it typically generates expansive wines, often with more blunt force than sting; nevertheless, still entirely grand cru material. In Blanchots’ defense, needlepoint texture and electricity are commonly stronger attributes for the left bank. Christophe’s Blanchots comes from conventionally farmed vines of more than forty years on white topsoil on the famous Kimmerigdian marl bedrock of the area. The wine is aged in 60% inox and 40% oak (with roughly one-third of the oak new) for eighteen months. Sébastien doesn’t employ cellar tricks, so one tastes the cru and quality of the farming. He purchases his Blanchots fruit, as he does his newest grand cru, Les Preuses.

The Les Preuses grapes are organically farmed, and it shows in the wine. While maintaining its grand cru strength, it’s full of life, and more lifted and subtle, the latter element harder to achieve with sustainably farmed vineyards. Since I tasted all the new young vintages from Sébastien from 2012 up to now, the 2020 Les Preuses is unquestionably the greatest young Christophe wine I’ve experienced shortly after bottling—an important distinction. (Tasting newly bottled wines can be a fool’s game. Most of the time for months after bottling they’re off-balance and stretched uncomfortably thin and tight, and generally unresponsive to any attempted coaxing. During my wine production years, the first couple of weeks after bottling may show well, but then wines tend to tighten and shut down for some months. Often it seemed to take about as much time in bottle as their élevage after the bottling for many wines to recalibrate to their previous form. However, I suppose that wines aged extremely long in the cellar, like three or more years, may not behave the same way.) I hope this incredible effort lives up to its promise during my first interaction with it. The 2020 Les Preuses seemed to be a pivotal wine for Sébastien to go from a toe in the water to a full jump into organic culture, a point I’ve pressed him on since our first meeting in 2013. The difference between organic and non-organic wines in a region so particular as Chablis can be obviously clear (with few exceptions, and one extremely notable one…) for wines that are made to highlight their terroirs, not the cleverness and over-intellectualization in the cellar work.

Stéphane Rousset’s Crozes-Hermitage and Saint-Joseph range represents one of the greatest terroir-focused values in all the Northern Rhône. Virtues of the sublime marriage between Syrah and Northern Rhône granite and schist are commonly extolled, and there are few as fair-priced and thrilling as Rousset’s. Stéphane Crozes-Hermitage vineyards, unlike most of the low altitude, flat and gently sloping Crozes-Hermitage areas, are on steep rock terraces difficult to work by tractor, or on terraces with many vine rows, like the eastern end of Hermitage. Sharing the likes of Saint-Joseph, Hermitage, Cornas, and Côte-Rôtie, most of his wines sell for a fraction of those from more illustrious appellations, but with work that puts the same heavy toll on his body. I usually meet Stéphane in the afternoon when he’s just out of the vineyards, bushed but with a big smile, his bright cheeks rosy from the sun, ready to give me the tour—which always includes a visit to say hello to the precariously steep and rocky Les Picaudières, one of my favorite vineyards in Europe and one of the truest, quietly great terroir treasures in the Rhône Valley. Each time I drink his wines I am reminded of his daily toil with his father, Robert, who still works by Stéphane’s side, as they race to stay ahead of today’s runaway sunny seasons, followed by a full sprint at harvest time to beat the birds, the bees and the relentless sun when the grapes are in the zone.

Located behind Hermitage and across the Rhône River from some of Saint-Joseph’s best steep granite vineyards in Saint-Jean-de-Muzols and Vion, Stéphane’s Crozes-Hermitage vineyards are in Gervans, Érôme, and Crozes-Hermitage (the appellation’s namesake), the original communes before the appellation’s extensive eastern and southern expansion. Stéphane’s vineyards are unlike any of your standard Crozes-Hermitage. Much of the appellation wraps around Hermitage from its eastern flank to the south on an expansive flood plain. These areas have a multitude of sedimentary rock and topsoil from mostly river deposits with some areas richer in calcareous-rich depositions but most are a mix of silt, sand, gravel and cobbles. Behind Hermitage it’s mostly a continuation of the acidic granite bedrock of Hermitage’s far western flank, with vineyards lower down on the granite terraces sometimes frosted with slightly yellowish white loess, a fine-grained wind-blown sediment rich in calcium-carbonate. All Stéphane’s Syrah vines are on granite bedrock with sections heavier in loess topsoil reserved for the Crozes-Hermitage appellation red and the vineyards with the deepest loess topsoil are reserved for his small production of whites.

2019 may be the most promising vintage in Stéphane’s neck of the Crozes-Hermitage appellation since 2015 or 2016. He is a fan of both 2019 & 2020 but says that 2019 maintained a higher level of acidity compared to the surrounding vintages because of dehydration from the heat. There is a high variability reported between regions, but Stéphane finds his to be more structured than his 2020s. 2020 was the earliest-picked vintage since 2003 (while maintaining more fresh fruits than this deeply hydric-stressed vintage) with wines said to be easy early drinkers.

Sourced from a mix of mostly granitic vineyard sites scattered around the hillsides behind Hermitage and some terraces closer to the river on granite bedrock with a mix of loess and granite sand topsoil is Stéphane’s first red in the lineup, the 2020 Crozes-Hermitage Rouge. Aged in a mix of primarily concrete and inox vats with a little in oak, this wine is the most accessible out of the gates. The loess contribution softens the edges, lifts the aromatics and curbs the deep saltiness often imparted by the granitic soil. A crowd pleaser, this pure Syrah is also very serious juice led by the pedigree of its geological genetics that bring its terroirs into focus more than the variety—similarly to terroirs like Cornas, Saint-Joseph and Côte-Rôtie. Crozes-Hermitage is an appellation where a relative shoestring wine budget won’t hinder studying the influence of how many different soil types can create very different wines made from a single red grape variety. One only needs to know the location of each producer’s vineyards. This will take a bit of research, made easy by the wealth of accessible information nowadays, particularly in the fabulous Rhône books put out by authors Remington Norman and John Livingstone-Learmonth. (There’s a new book out, by Decanter contributing editor Matt Walls, that I haven’t dug into yet, but I’ve heard it’s also a good place to start.)

During my first visit with Stéphane in the spring of 2017, a particular Syrah stood out among the different parcels he vinified separately before blending them into the basic appellation wine. Equally good and already on qualitative par with his Saint-Joseph and Les Picaudières, I asked why he didn’t also bottle it on its own. He shrugged, grinned, contemplated, and we moved on—my first insight into the deep humility of this quiet and jovial man that by the end of the day is clearly spent. I pushed him to bottle it alone via email and during all of my subsequent visits.

The 2019 Crozes-Hermitage “Les Méjeans” is the new addition to the range, and a worthwhile exploration for anyone interested in Stéphane’s wines and high altitude, granite-based Northern Rhône Syrah. Les Méjeans comes from three different parcels only a golf shot from each other and rising to as high as 350m (maybe as high as it gets in the appellation), all within a small area known as Les Méjeans. This is the only purely granite-based Crozes-Hermitage Stéphane bottles, and it tastes like it: salt, earth, animal and pepper before fruit and flower, rustic but elegant and deep graphite-like mineral textures that keep it fresh. The steeply terraced vineyard of the three has the most fine-grained sand (an unexpectedly small grain, like beach sand), and the other two are more gradually sloped, lending support for their vines against the hydric stress of these fully exposed sites on top of the hill. We imported 600 bottles for the entire US market (he didn’t make much more than that and we both wanted to be conservative out of the gates), so let us know your interest level so we can make sure you get a shot at it.

The decision is often split between Rousset’s Saint-Joseph and Crozes-Hermitage “Les Picaudières” in preference depending on the taster and the amount of time the wines are open. Les Picaudières is often less immediately approachable in the context of the two, but it’s still very accessible straight away. Les Picaudières takes time to reveal its full depth and expansion while the Saint-Joseph usually hits its mark in about fifteen minutes and remains in a heightened state and on a straight line for hours. In my opinion, Les Picaudières is the greater terroir between the two, but it will take time once opened for it to take control of the standoff, eventually evolving so much that one begins to understand that it is well beyond its appellation in hierarchy. Likely a geological transition area, the vineyard’s bedrock, on an extremely steep south face surrounded by forest on all sides except where it tops out on a ridgeline, ranges somewhere between granite and schist—perhaps slightly more of the latter rock type. The topsoil on these precarious terraces is entirely derived from its bedrock, landing this wine with some elements found in the great schist vineyards of Côte-Rôtie and the granite sites of nearby Hermitage (where only on its west flank it’s mostly granite) and the granitic southern end of Saint-Joseph across the way. Les Picaudières is no ordinary Crozes-Hermitage (as you can see by the photos), and texturally it is almost unrecognizable as a Crozes-Hermitage—except its price! Textured with fresh metal-iodine-graphite palate aromas and mouthfeel, it’s led by stronger savory, earthy and rustic notes more than fruit. If you walk down the path with this wine, give it the proper time to reveal all of its hand or you will miss the main event.

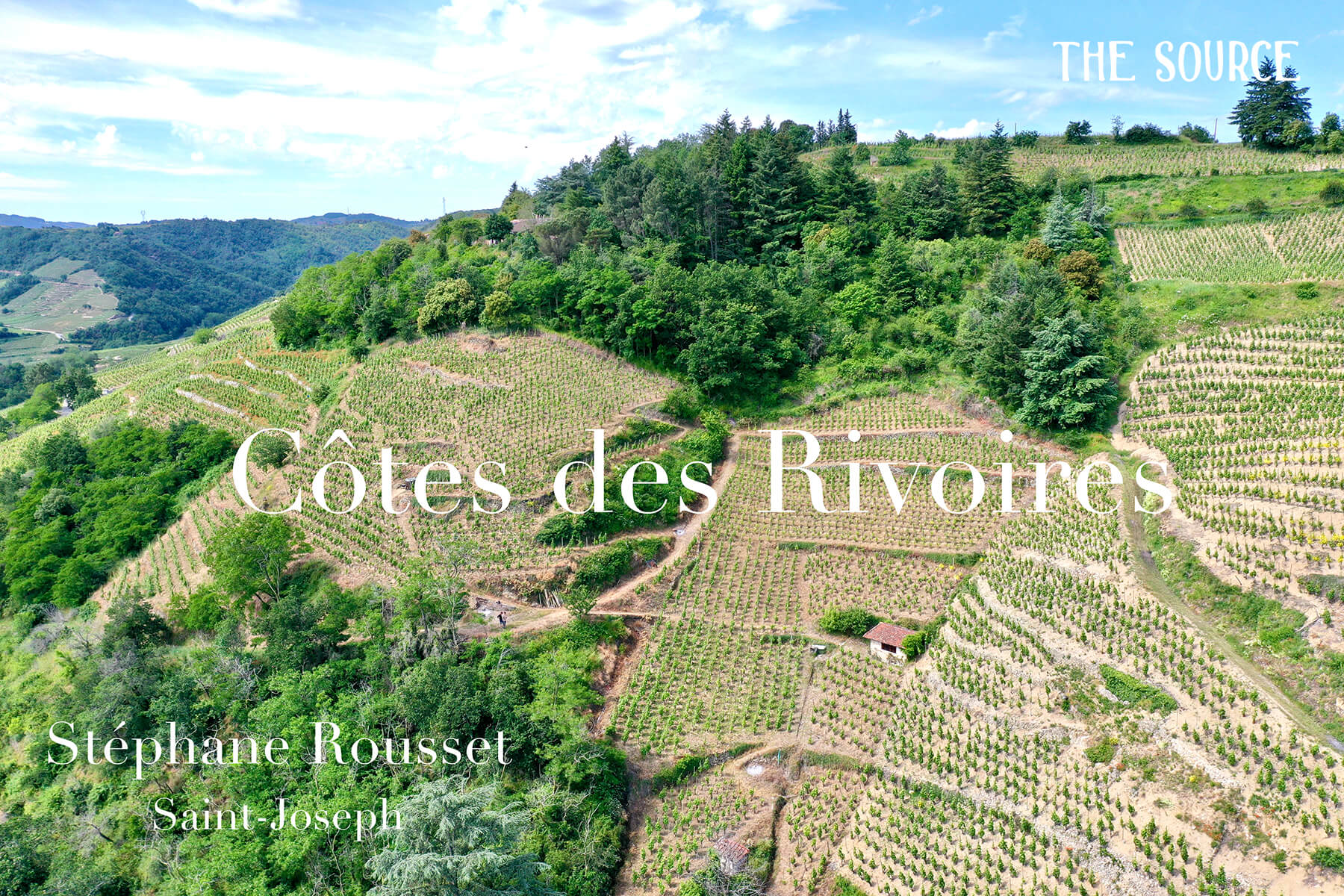

Rousset’s Saint-Joseph is now labeled Saint-Joseph “Côte des Rivoires.” During my discussion with the Roussets about revamping their range with the addition of Les Méjeans, I also suggested they add to the label the site name they use exclusively for their Saint-Joseph. (Rousset has a ton of great sites that may warrant future individual bottlings, and they may have a third new in the mix—possibly a grape selection from all of their Crozes-Hermitage vineyards in honor of previous generations.) Rousset has two adjacent east-facing plots inside one of Saint-Joseph’s top communes, Tournon. It’s a nail-bitingly steep drive up the hill with a complete open view into the massive valley to the east. At times it would seem like floating up the hill if it weren’t for the bumpy road and granite terraces and rock wall just a few feet from one window. Aged similarly to Les Picaudières and Les Méjeans in a mix of old and new barrels (roughly 10-20% new) for about a year before bottling, it is the most forward and perhaps most elegant wine in Rousset’s lieu-dit range, at least immediately upon pulling the cork. Apparent in pedigree, this classic southern Saint-Joseph springs into action upon opening, releasing esters of water-stressed wild shrubs and garrigue (with much less violet and lavender compared to many others in the area), and more earth and sun-rich cherry, and fresh but ripe fig. Perhaps the saltiest and softest texture between Rousset’s lieux-dits, it’s usually the frontrunner in the first hour and the most charming.

Nothing new to report with Clos Fornelli, possibly Corsica’s most friendly-priced, organically grown, fresh and simply delicious wines from the island. Arriving are the 2021 La Robe d’Ange Blanc, a pure Vermentinu, 2021 La Robe d’Ange Rosé made entirely from Sciacarello, and 2020 La Robe d’Ange Rouge, also composed entirely of this wonderful queen of the island, my favorite Corsican grape, Sciacarello. All were born on soils derived from the erosion of the geological formation referred to as Alpine Corsica on the northeast of the island on a series of terraces that Josée Vanucci and her husband, Fabrice Couloumère, tend their vines. (Alpine Corsica is named as such because it was developed during the Alpine orogeny, while the granite parts, the dominant geological formation on the island, known as Crystalline Corsica, date further back to Pangaean time.) This eastern side of the island with mostly eastern and southern exposures butted up the island’s mountains (yes, surprisingly a lot of mountain area in Corsica) protect them from the scorching early evening summer and autumnal sun, leaving them fresher than most of the wines from the island’s west side where many of Corsica’s famous wines come from. Clos Fornelli’s wines are raised mostly in concrete vats with some old 500-liter barrels. We can’t keep these in stock once they’re here, so don’t wait. Josée and Fabrice have everything sold just months after their release, making each year a one-shot opportunity.

As you likely know, the big game for Domaine Jean Collet is Chablis, but Romain Collet was always interested in Saint-Bris, a neighboring appellation with the same bedrock, but on shallower rocky soils—soils mostly too spare for Chardonnay to thrive. Only a twenty minute drive from Chablis, this is Sauvignon Blanc territory and the 2020 Saint-Bris is the third vintage for Romain. With the prices of Sancerre making steady but notable increases each year, this Saint-Bris should be a consideration for by-the-glass programs in restaurants and a great starter to a summertime meal.

Domaine Chardigny has a couple new vintages for us to feast on. These last few seasons were hit hard by Mother Nature, leaving much less compared to prior years. As regularly touted over the years since our first imported vintage (2016) from the Chardigny brothers, I believe both 2020 and 2021 are exceptional years for them and jump a few notches up from the years before, with 2019 a solid pregame for the breakthrough. The 2021 Beaujolais-Leynes is their newest Beaujolais label and made from a blend of many different parcels—some from the Beaujolais appellation classification with a mix of grapes from their two crus, Clos du Chapitre and À la Folie, all entirely EU organic certified wines. Leynes leads with red-fruited charm, while its complexity is tucked further inside. The 2020 Saint-Amour “Clos du Chapitre” is likely the best wine they’ve put to bottle—at least in comparison to any that predate the 2021s. (I don’t yet know how the 2021 crus panned out since they were bottled.) This vineyard is flat and visually uninspiring compared to much of Beaujolais’ scenic hillside vineyards, but regardless it performs exceptionally. Regal, with the greater polish between all Chardigny Beaujolais wines, the 2020 is a knockout. This was the vintage out of barrel that stunned me with its Côte d’Or likeness, despite differences in grapes. The Chardignys are making serious strides in the natural wine world all the while keeping their record clean from the rodent smell so commonly found in high-brow organic and natural Beaujolais these days. Don’t miss this wine from these young stars.

As expressed previously in our September 2021 Newsletter, if Pique-Basse owner/vigneron, Olivier Tropet, had vineyards in appellations like Côte Rôtie, Cornas or Châteauneuf-du-Pape, he’d be more likely to garner wide acclaim, but he lives in Roaix, the Southern Rhône Valley’s tiniest Côtes-du-Rhône Village appellation. It’s hard to believe what he achieves within this relatively unknown village with his range of wines that have been organically certified since 2009 and are as soulful as they are exquisitely crafted. Arriving is the new release, 2020 La Brusquembille, a blend of 70% Syrah and 30% Carignan, and a reload of 2019 Le Chasse-Coeur, a blend of 80% Grenache, 10% Syrah and 10% Carignan. Syrah from the Southern Rhône Valley is often not that compelling because it can be a little weedy and lacking in the cool spice and exotic notes that come with Syrah further up into the Northern Rhône Valley. However, La Brusquembille may throw you for a loop if you share this opinion, especially with the 2020 clocking in at a modest (for the Southern Rhône) 13.5% alcohol. Without the Carignan to add more southern charm, it might easily be mistaken for a Crozes-Hermitage from a great year above the Chassis plain up by Mercurol, where this appellation’s terraced limestone vineyards lie and are quite similar to the limestone bedrock and topsoil at the vineyards of Pique-Basse, without the loess sediments common in Mercurol. It’s not as sleek in profile because it’s still from the south, but its savory qualities and red and black fruit nuances can be a close match. Despite the alcohol degree in the 2019 hitting 14.5% (while the target is always between 13%-14%), Olivier tries to pick the grapes for Le Chasse-Coeur on the earlier side for Grenache, a grape that has a hard time reaching phenolic maturity at comparative sugar levels as grapes like Syrah or Pinot Noir, and farms accordingly for earlier ripeness with the intention to maintain more freshness. It’s more dominated by red fruit notes than black—perhaps that’s what the bright red label is hinting at—and aged in cement vats, and sometimes stainless steel if the vintage is plentiful, to preserve the tension and to avoid Grenache’s predisposition for unwanted oxidation. Both Le Chasse-Coeur and La Brusquembille offer immense value for such serious wines.

(Left to right: Leigh Ready, Mateus, Hadley Kemp & Victoria Diggs)

No longer successfully on the run from Covid, I tested positive on my birthday on my forty-day European tour. You probably had it already and know what to expect, but I was caught off guard. I experienced unusually intense allergies prompted by a wet spring that ended with a two-day rise of more than twenty-five degrees (F) and lasted for three weeks and pushed every plant in the Czech Republic, Austria and Italy into full-throttle growth, ending my successful spring running streak (literally). Then Covid hit—surely contracted on the three different trains between Milan to Frankfurt. Milano’s Stazione Centrale is a perfectly orchestrated Covid super-spreader daily event, swarming and—at least what seemed to be—not a single person masked up until forced to by the train conductors inside the train. It seemed that every unmasked passenger walked through our train car on the way to theirs; I guess it’s not so clear for some which car is theirs from the outside indicators on the train. Still mandatory on public transport in Italy, the passengers and the crew promptly unmasked once into Switzerland then masked up again crossing into Germany. Silly.

It felt like a light spring cold at first (and frankly, initially no different than the allergies I was experiencing) and I thought it couldn’t be Covid. The horrors of this coronavirus shared by everyone seemed intense and my initial symptoms weren’t aggressive enough. The lower body aches set in while touring Arturo Miguel’s (Bodega Artuke) Rioja Alavesa vineyards. The wind was bitterly cold, strong enough to rip shoots off vines that weren’t yet tipped (a quick manual breaking of the shoot tips to stop their vertical growth, a necessity in most of Rioja Alavesa and Rioja Alta vineyards at higher altitudes that take the full force of the north winds shrieking down the Sierra Cantabrian mountains), and I was cold enough and in my favorite element to not realize that I was already mid-fever. By the time we got out of the cold, I began to thaw in his cellar. Still oblivious to my condition, my head began to heat up and slowly made its way to full Ghost Rider. I’ve never been so hot!

Covid is indeed a bizarre experience. I was lucky to get Covid-light with mild symptoms over the first few days, irritating but not debilitating aches, and a fever that lasted all of about sixteen hours—maybe because my head rushed into a ready-to-erupt volcano state and peaked early. A few days after the major symptoms passed, as many also said might happen, my lungs tightened (a somewhat normal experience for me with my minor asthma), feelings of depression and a lack of motivation (neither normal for me), and physically, mentally, and emotionally disconnected—zombie-like; lightly and uncomfortably, eternally stoned. No matter what I did or where I went for necessities like tests, masks, food, and water, I felt guilty for being close to anyone. My travel companions, Victoria, Leigh, and Hadley were empathetic to its untimeliness, as I was supposed to guide them through their trip in Iberia. They all had it in January and some were also recently boosted, so they were pretty chill with my new condition. Eventually I rented a different car in Logroño, the central hub of Rioja, and drove their same scenic route through my favorite section of Spain, the verdant and mystical coastal landscape from País Vasco, Cantabria, and Asturias, finally dropping the car in Galicia. My predicament was exacerbated by my wife’s mother’s visit from Chile, a normal occurence when I go on lengthy benders my wife doesn’t want to do with me anymore. Neither of them previously had Covid, so I couldn’t go home. I couldn’t visit producers. I was adrift on a strangely lonely planet for days—a culpable castaway surrounded by people I wasn’t supposed to even see. Friends and family kept their distance and, unintentionally, harbored a look of mistrust, like I’m going to lash out at them, or maybe they saw me as a potential dead man walking and didn’t want to break the news to me if they saw it worsen.

In Santiago de Compostela with nowhere to go and nothing to do, I holed up outside of town for a night in a small hotel—cheap, but better than expected. The sun’s angelic evening beams illuminated the Santiago green countryside, and the temperature was warm but breezy and friendly. Still positive but a week past the heavier symptoms, I convinced Andrea to pick me up. Benched in the backseat, no hugs or kisses after a month apart, fully masked up, windows down for the two-hour drive with a feeling like we were on the rocks (although we weren’t) I hid out at home until those pesky coronavirus proteins completely expelled from my nose. Thankfully, I didn’t lose my taste or smell, so my job remains somewhat secure. (If I did lose them, I probably wouldn’t tell anyone anyway…)

Regardless of my personal woes, the trip was very successful for me prior to the Covid battle and there was an immense amount of joyful and revelatory wines experienced, even if I missed sixteen Iberian visits. Making this list was hard. There are certainly many more than fifteen wines that deserve to be on it, but it’s trimmed down to the goosebump-inducing highlights and breakthroughs. Missing here is most of Iberia and our visit with a potential new producer in Piemonte that may have stolen the spotlight of the whole trip, but next month’s newsletter will have top picks from our expert staff. My top 15 in no particular order:

Veyder-Malberg 2021 Riesling Bruck. All 2021s from Peter are wonderful and the Austrian Grüner Veltliners in general must be my favorite vintage ever for this variety. In fact, any one of Peter’s Grüner Veltliner crus could’ve made this list.

Malat 2019 Riesling Pfaffenberg. 2019 is very successful from Michael Malat and I think they are his best wines to date, but the 2021s will be a strong follow and will surely be in the running for his “best ever,” next to the 2019s.

Tegernseerhof 2021 Steinertal Riesling Smaragd. 2021 was another extremely successful vintage across Martin Mittelbach’s entire range. As some of you know, his 2019s were a smashing success and finally the wine press gave him appropriately high marks.

La Casaccia 2019 Freisa di Monferrato “Monfiorenza” is a modestly priced, joy-filled wine with massive heart, made by maybe the happiest Italian man I’ve ever met, Giovanni Rava, and his lovely family. I never thought Freisa could be so seductive and delicious! 2021 seems to be its equal as well! (Sadly, they forwent on bottling any 2020 because of market concerns due to extensive shutdown periods in Italy during Covid.)

Fletcher 2019 Barbaresco Roncaglie is a new bottling for Dave, and all of his 2019 Barbaresco wines are extremely impressive. Faset and Starderi were stunners on their own, but Roncaglie ran away with it—not surprisingly, given that the fruit all came from Poderi Colla!

Poderi Colla 2019 Barbaresco Roncaglie is unquestionably in the top 3 wines of the trip, possibly the top wine for me. It’s far too good for the price and will surely be one of the greatest wines we will have imported since our start in 2010.

Fliederhof 2020 Santa Magdalener “Gaia” is a mega-breakthrough Schiava made with 100% whole clusters and almost no extraction. It scored extremely high on both my pleasure and seriousness meters. The young Martin Ramoser is nailing it and he’s got a few more years to go before he even crosses thirty. Problem is that we will only get 48 bottles…

Picchioni 2018 Buttafuoco dell’Oltrepò Pavese “Riva Bianca” has more X-factor than the entire Marvel Universe. Our San Diego representative, Tyler Kavanaugh had cartoon eyes popping out of his head through this entire visit. Andrea Picchioni drove it home with exquisite bottles of 1999 & 2010 Riva Bianca. One day, people will realize that Picchioni is the Mega to the late Maga. RIP Lino. We were lucky to meet Lino a year before his passing. He was much sweeter than any of us expected based on the stories told.

Monti Perini 2019 Bramaterra wasn’t bottled yet and possibly will not be labeled with the Bramaterra appellation because it’s in too perfect of a moment and hasn’t yet had its mandatory time in wood required by the appellation. The 2017 and 2018 may be just as good as the 2019. This trio of wines was enlightening. Sadly, Andrea lost everything to Mother Nature in both 2020 and 2021. Almost throwing in the towel, I convinced him that our industry would support him through these times. We do our best for the little guy!

Davide Carlone 2019 Boca “Adele” wasn’t bottled yet, but the tastings out of botte were riveting. Some of the best wines of the trip were in this cellar. Carlone is crazy in the best way, and with Cristiano Garella advising in the cellar, he will be one of Piemonte’s best, rivaling the biggest names further south in the Langhe.

Enrico Togni’s 2021 Martina Erbanno Rosato out of concrete vat. Enrico’s cellar is rustic and he flies by the seat of his pants, but what comes out of those vats seem like miracles. Special guy, special wines. This pink wine is as serious as it gets for rosé with unique character and less enological polish. Sadly, its quantities are severely limited.

Wechsler 2021 Kirchspiel Riesling Kabinett, is a savagely delicious and sharp new Riesling from this multifaceted talent! Unfortunately, there are only 20 cases coming in for the entire US. Our visit with Katharina revealed so many simply delicious and very complex wines within her natural wine range, “Cloudy by Nature,” and her classical dry Riesling range. Now, we have to add her wholloping knock-out-of-the-park Kirchspiel Kabinett (and Morstein Spätlese!) as another major success. Five wines from her could’ve made this list. (I’ll let you know more about them when they are closer to our shores.)

Xesteiriña 2020 Albariño, a crackling laser beam shooting from a plank of igneous and metamorphic rock, is a fabulous new project in Rías Baixas that’s going to shake it up! Again, too few bottles to be had by all.

Quinta da Carolina 2021 Xis Amarelo tasted out of barrel may also be top 3 of the trip. Somehow Luis (whose day job is the winemaker for Dirk Niepoort’s still wine range since about five or six years—post Luis Seabra) is channeling some major red Burgundian juju: think Mugnier and Fourrier birthing a schist Amarelo baby from the Douro. Everything tasted out of barrel from Luis was superstar material and there could be more wines from him on the list too. Also too limited!

Mateus Nicolau de Almeida’s Porto Branco. Never did I imagine a Port wine would make my top 15! Theresa and Mateus’s (pictured further above) wines channel their openness to let terroir and vintage fully speak, and this is one of the things that makes them so special. Authenticity at its peak is found inside this quirky, fun-loving duo and their deeply minerally, savory Douro wines. Being in their company made me think a little more deeply about my place in the world, and I truly believe it would do the same for anyone.