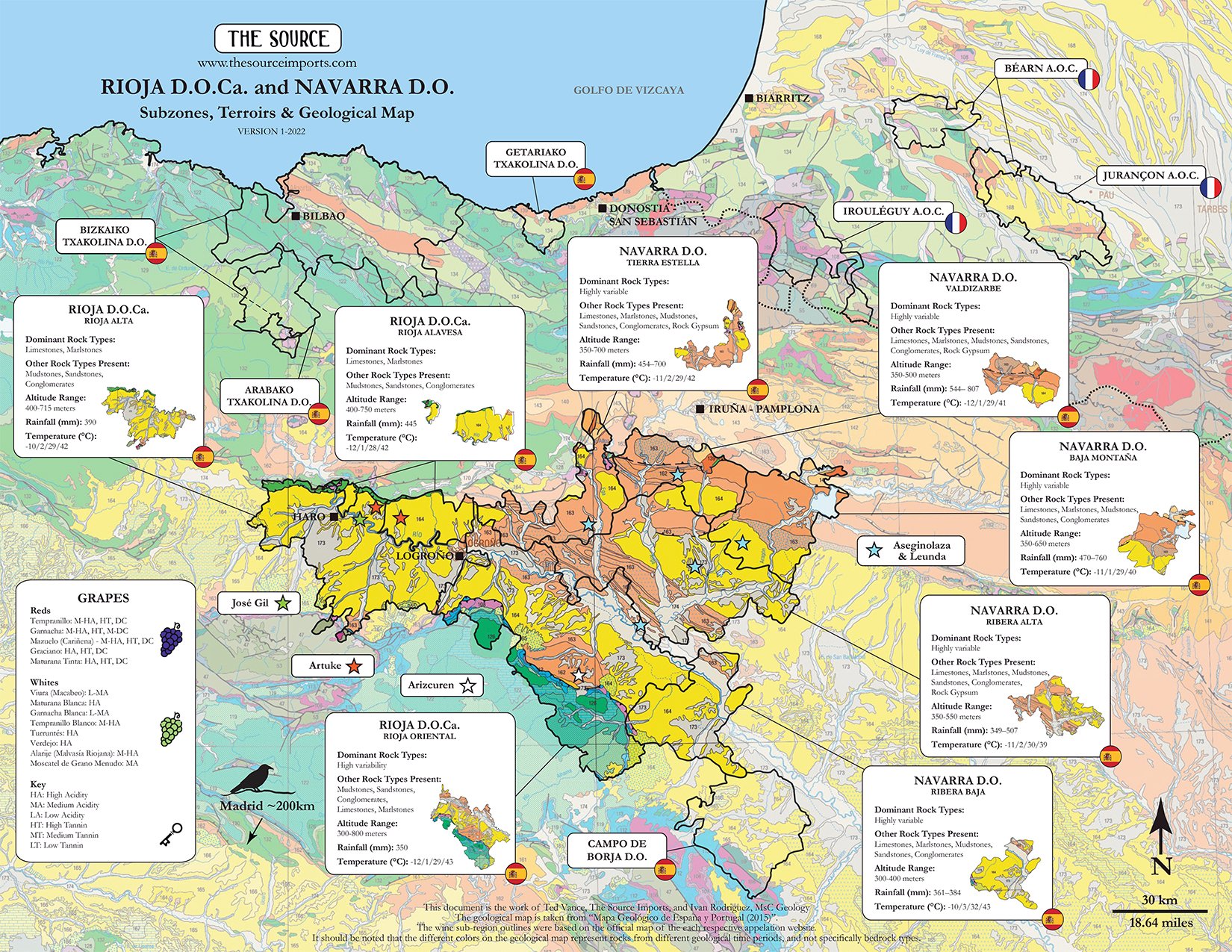

After doing tons of research, Spanish geologist Ivan Rodriguez and I finished our latest terroir map, as well as a short essay on some of the geological story between Navarra and Rioja, both of which are downloadable here. Also, on our website profile of Navarra producer, Aseginolaza & Leunda, there is a deeper exploration of how Navarra, even though it has an equally compelling terroir, began to fall behind Rioja more than a century ago, despite that both regions were once highly celebrated as one. It also compares Garnacha and Tempranillo, which you can read about here.

Good timing for the Tim Atkin report on Rioja! Atkin was very favorable to Javier’s wines and he was a regular in his extensive feature about producers filled with good information, and good wine! The report is a must read for anyone interested in what they should be looking for during this European wine region’s renaissance. Rioja is Spain’s most historically important red wine region, and, if you believe in the merit of terroir, you can’t ignore this one. Most of the red wine regions that dominated the fine wine marketplace over the last decades are now registering much higher alcohol contents. Côte d’Or is often beyond 14% (though many won’t change the labels to reflect their true numbers), and places like Barolo and Barbaresco regularly clock over 15% now, and also stay quiet about their numbers. Châteauneuf-du-Pape has been simply shameless in producing wines well beyond 15% for decades now because critics saw monsters with balance and gave monster scores (and gave most of us monster headaches). I remember discussing with Emmanuel Reynaud, from Château Rayas, in his cellar about low alcohol wines. He smiled and explained that while this trend is happening, he wonders if people know, or care, that his wines regularly hit 16%, but remain balanced. They do, and, yes, they are balanced, and that’s what should count, no? You just need to measure your pregame wines before you dive into the Rayas range because they’re worthy of the experience and are always better served slowly than a rapid glugging before moving on to your next bottle.

One of the longer-term assets (by climate change standards at least) in the face of our planet heating up in Rioja is its altitude and potential for planting and replanting in even higher zones. While lower-lying areas are bound to suffer more from the heat and spring frost, Rioja has many locations that sit well above 500m, and as high as 900m; in the past there were a lot of vineyards planted above 800m, especially in the southern mountain range of the Systema Ibérico, in Rioja’s Oriental subzone, where Javier Arizcuren grows his grapes at high altitudes.

Javier Arizcuren is one of Rioja’s most exciting new talents. He’s also a very well-known and highly respected architect, and his cellar in Logroño is just next door to his very successful, but modestly outfitted architectural firm. With the help of his father, Javier spends his “spare time” focused on rescuing high-altitude, ancient Garnacha and Mazuelo (the local name for Cariñena/Carignan) vineyards that managed to survive both phylloxera, and the trend of replacing these historic vines with the popular Tempranillo, an early-ripening grape that is only a small part of this region’s long history despite its dominance today. (Tempranillo is expected to have more trouble with climate change than Garnacha and Mazuelo due to its more precocious nature.) His experience with architecture and his insatiable curiosity (a trait many of us in the wine business can relate to) leads him down rabbit holes of possibilities with broad experimentation (a rarity in this often predictable and extremely conservative wine region), so that he may better understand the aesthetic of each site and build on its strengths using various fermentation and aging techniques, and different aging vessels, from concrete eggs, porcelain, amphora, and, of course, oak. During a dinner with him last month, we discussed architecture and interior design. He explained that spaces have a particular personality and that you must be open to collaborating with them as much as dictating what you want them to be. I can see that he approaches his wines with this same respect and openness.

He’s in his early fifties, and with just over ten harvests made in his cellar, there are few who show as much promise as Javier. He’s sharp and his eyes reveal a state of constant contemplation and openness, and he earnestly and humbly listens to everything said without interruption, like he’s downloading your words to his hard drive. I expect big things from him in the coming years because his back isn’t against the wall to make financial compromises to stay afloat due to the financial backing of his architectural career. While he’s an entirely self-made man from humble beginnings in a very competitive field (and is friends with many of the region’s legends for whom he’s helped rebuild houses and bodegas), it remains a true pleasure to have an exchange with him. Hanging around guys like Javier makes me realize how little I know about what I do compared to what he knows about his primary trade—he’s truly cut from the same cloth as our friends, Peter Veyder-Malberg, and Olivier Lamy.

Javier feels that the higher altitude sites in Rioja Oriental are a solid bet for the future of Rioja for many reasons: they are later to ripen and are also later to start the vegetative cycle (which helps to avoid spring frost); the Serra de Yerga mountains have a lot of limestone-rich terroirs in higher locations; he continues to find ancient, pre-phylloxera vines and nearly extinct varieties that made it past the regional homogenization phase with Tempranillo. The Tempranillo he grows is good, but the historical varieties here are Garnacha, and before that, Mazuelo.

The 2019 Rioja “Monte Gatún” clocks 13% alcohol, a very modest figure considering the heat of this vintage; it’s generally the direction he wants to go with his wines, showcasing their balance with a duality of roundness and angularity. It’s a blend of Tempranillo with 15% Garnacha and 10% Graciano. It’s a straightforward, full-flavored Rioja with great freshness—an impressive starting block for Javier’s reds. I had a Graciano sample out of barrel with Javier just three weeks ago that was simply riveting. I’d never tasted Graciano on its own (and if I did, it wasn’t memorable enough!), and man, what promise that grape has! Graciano could be the grape of the future regarding climate change. It’s so insanely balanced for such high acidity, and that’s the kind of thing that gets me fired up. The only problem is that he made a single barrel each vintage… Come on Javi! What a tease!

As mentioned, curiosity drives Javier, and his 2019 Sologarnacha Anfora—as you guessed it, only Garnacha and raised in amphora—needs to be tasted. I’ve never had Garnacha/Grenache in new oak barrels that have agreed with my sensibility with this grape (and most other wines, too), and have always enjoyed it out of more neutral aging vessels. Amphora Garnacha is another new and enjoyable experience for me. It’s aged for only five months to preserve just enough of the fruit aromas while allowing it to take on more earthy notes. It’s another lower alcohol Rioja wine at 13.5%.

The 2017 Solomazuelo is, you guessed it again, made entirely of Mazuelo, the historic, historic grape of Rioja. Before phylloxera, Mazuelo was the dominant variety in Rioja, but when it came time to replant, Garnacha was favored (for what reason I don’t know), and since the 1980s, these two grapes were both ousted by the mass proliferation of Tempranillo in all places Rioja. Mazuelo has incredibly good balance considering the juicy wines it can create. It’s a solid transmitter of terroir (very important to us) and maintains great class and complexity for a fuller throttle wine. I think that many see our wine selections in the more racy, even austere overall profile, but it’s not always the case. We have long pursued wines with great acidity and also focused on regions that will manage the climate crisis well during our generation’s time on this earth. Mazuelo and Javier’s project is in line with ours: the future is always met better with the preparations of today. Javier is headed to the hills to prepare for the onslaught of climate change, and places where the very late ripening and high acid varieties of Mazuelo, Graciano and Garnacha are his guide.

“Above all, I want my wines to express sincerity. Aromatically, I like that they show more organic notes of a real nature associated with fermentation, never “synthetic” aromas. But that doesn’t stop me from looking for the complexity that I think my terroir can achieve. I like that the vegetal rusticity of the Hondarrabi Zuri, Hondarrabi Zerratia and Izkiriota Txikia integrates perfectly with a more complex matrix framed by mineral notes and a more or less oxidative evolution without the use of sulfur, offering the wine a natural path to balance.

“I consider acidity to be a natural part of our wines, being much more integrated when the wine is less intervened. But I think that wine is made above all to be drunk, ingested, and so it should feel good—a like-it feeling that the body is in tune with it, and that is easily digestible. I want them to leave a good memory, combining that part of a certain indomitable nature with the part of elegance to which we want to take it in its upbringing. But I would also like it to reflect the particularity of the vintage, both climatic and the eventual intention of the vineyard in its evolution as a being.” –Alfredo Egia

The wines made in Txakoli by Alfredo Egia are radical for the region but not for the world, since he is committed to biodynamic farming and natural wine methods in one of the wine world’s most difficult places for this practice. And with the influence of Imanol Garay, the highly intense and fully committed Basque naturalist living in France whom he refers to as his mentor, he’s determined to harness the intense energy of Izkiriota Txikia (Petit Manseng) and Hondarrabi Zerratia (Petit Courbu) to give them a different expression, shape and energy, with a constant evolution upon opening that can last for days. These white wines grown on limestone marl walk the line with no added sulfur and I would suggest that they should be consumed earlier in their life to ensure captivity of one of their best moments. Whether they can age well without added sulfur or not remains to be seen, but since they have very low pH levels that usually sit below 3.20, and ta levels that can be well above 7.00, and are bone dry, they should be insulated for a while. Rebel Rebel (12.5% alc.) is the solo project of Alfredo, and Hegan Egin (13.5%) a joint venture between Alfredo, Imanol and their other partner, Gile Iturri.

My first interaction with Alfredo and his wines was almost exactly a year ago. The weather in Balmaseda was clear and crisp but icy cold. Thankfully there were moments in the sun that gave us a thaw, but in the shade it chilled us to the bone. My wife and I spent the morning with him in his vineyards and I returned again alone to taste the wines later in the day. I simply couldn’t get enough of Rebel Rebel and Hegan Egin as we worked our way through bottles of the 2018s and 2019s, while camped out in his vineyard and freezing our buns off. I’m convinced of Alfredo’s imminent stardom; his wines channel the spirit of the Loire Valley luminary, Richard Leroy, via Imanol Garay who spent time working with him prior to starting his own project, and now Imanol’s project with Alfredo.

Rebel Rebel and Hegan Egin both start with the Leroy-esque, indescribable x-factor, reductive/mineral pungent aromatic thrust (but much more delicately than Leroy’s) that somehow imparts textures into your nose and throat. They are both imbued with citrus notes and fresh, sweet greens and herbs of this verdant countryside, but after open for more than an hour they begin to grow apart in style with Rebel Rebel remaining more strict and Hegan Egin softening and broadening its mouthfeel and fleshiness. 2019 Rebel Rebel is a blend of 80% Hondarrabi Zerratia and 20% Izkiriota Txikia, while the 2019 Hegan Egin is 50% Hondarrabi Zerratia and 50% Izkiriota Txikia. Both shouldn’t be missed, but these wines have the familiar story of extremely low production. There were only 360 bottles of Rebel Rebel imported, and 120 bottles of Hegan Egin for the entire country. Hopefully more in the next vintage!

Suffice it to say, 2020 was a painful harvest for many European winegrowers. The mildew pressure was so high through most of the year leading up to harvest that there were tremendous losses. Cume do Avia continues their commitment to organic grape production, which they’ve done since the very beginning, but the losses in 2020 were more than 70%, a staggering and demoralizing number that shook their belief in the idea that organic farming is a financially sustainable philosophy in this part of the wine world where more than seventy inches of rainfall each year is the average and the mildew pressure knows few European equals outside of Galicia. I continue to do my best to encourage them to keep their heads up, but I know it’s hard. The good news is that what they did pull off the vines was in good health and, despite the challenges, they have topped their previous efforts with the four different wines bottled this year.

Cume do Avia’s 2020 Colleita 8 Branco has every white grape they harvested this year, as there are no single-varietal white wine bottlings due to the massive losses. 2020 was a cold year in general for the region which plays very well into the overall style of their white wines. This year’s version is as charming and serious as ever and warrants pursuit for those of you who have already fallen for their white wines over the last two years.

Arraiano Tinto comes from grapes the Cume clan help to farm with some of their relatives near their estate vineyards. It is also another step up from last year’s, if not with a little more cut to it while maintaining its upfront appeal, and Colleita 8 Tinto must be the best to date. Granted, I’ve said that every year since we’ve imported their wines, but it’s always true… The 2020 version (No. 8) has everything in it, except about sixty cases worth of Brancellao they bottled separately. It still has a load of their Brancellao, all of their Caiño Longo, Sousón, and Ferrol, and all the other micro-bits of whatever other varieties they have among the fifteen or so planted on their small patch of extremely geologically diverse bedrock and dirt. Normally there are two other single-varietal wines (Caíño Longo and Sousón), and their Dos Canotos Tinto, a blend of all the best parts into one wine. This year, it’s all there in Colleita 8, and that makes it one heck of a wine for its price.

The 2020 Brancellao, when young, was the best to date I tasted in barrel. Aromatically striking, it had even more x-factor than the previous years. Materials were a problem to get this year in time for bottling—a challenge that started across Europe in 2021 and remains a problem. They bottled a few months later than usual, but perhaps it will serve the wine well by softening its approach. It shows a little more earth than sky this year (maybe that’s the x-factor?) and exhibits a broader range of nuances than the previous years. This grape is special and this vintage shows its capacity for diversity while maintaining its quality.

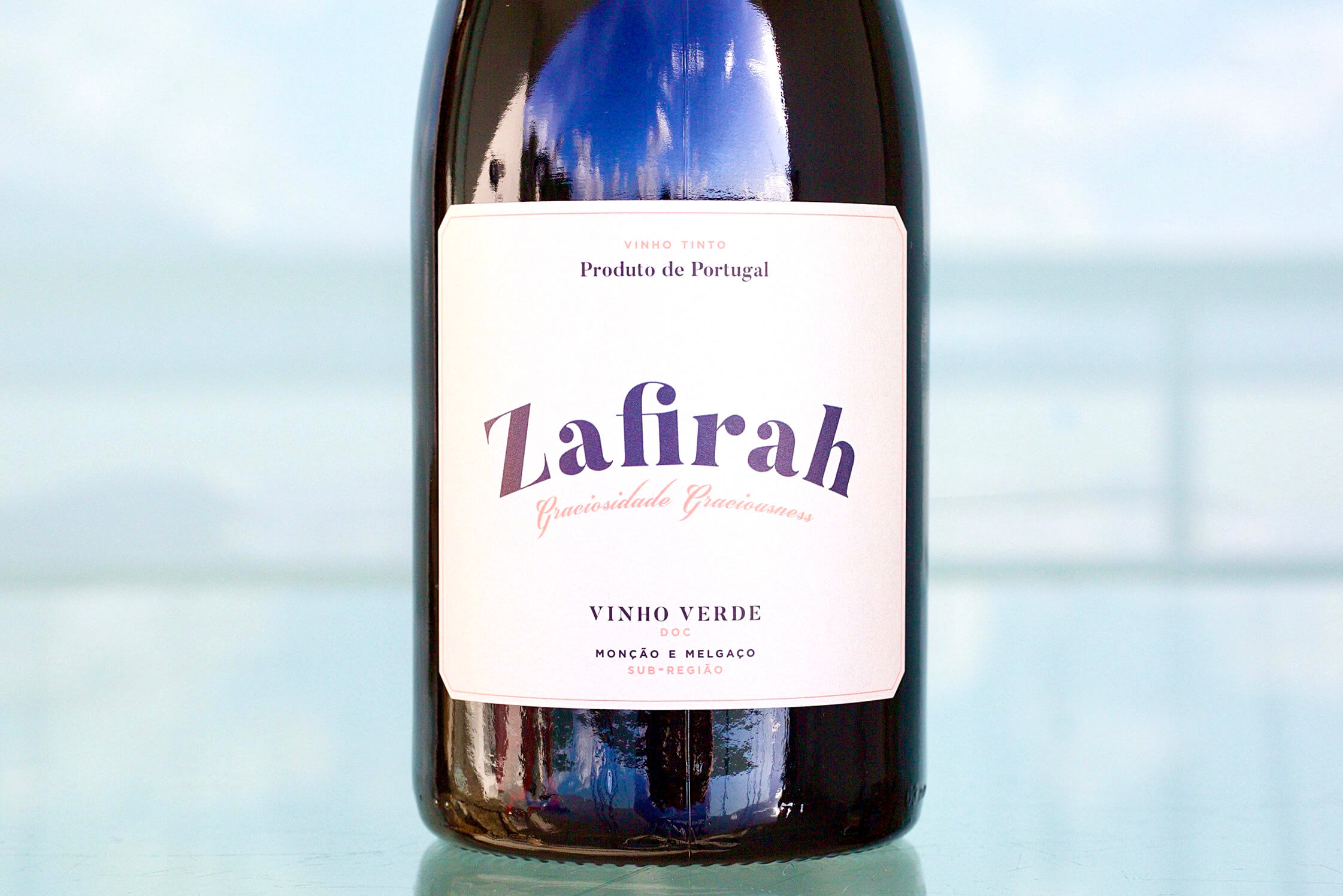

While you might never see a picture on the cover of Wine Spectator of a Vinho Verde micro-producer who makes 11% alcohol reds with razor-sharp edges and deeply earthy notes, Constantino Ramos, one of my great friends since we moved to Portugal, was just voted one of the four Enólogo Revelação do Ano (the winemaker revelation of the year) by Revista de Vinhos, an important Portuguese wine publication. Constantino is hitting the road with me and my team a little bit this year to explore more wine regions outside of his region, Monção e Melgaço. Already well traveled after working a harvest in Chile some years ago for the DeMartino family, he’s always interested to learn and experience new things and made numerous visits all over Europe to some serious addresses with his former boss and continuing mentor, Anselmo Mendes; Constantino went totally solo at the beginning of this year with own projects. He’s also crazy in love with Nebbiolo, which is one of the many reasons we get along so well—he has taken over as my Nebbiolo drinking buddy! His new release of 2020 Zafirah is, like last year, in short supply. Best served slightly chilled, it’s another one of those northern Iberian reds that feels as much like a white as it does a red, except its tannin and dry extract. It’s a blend of ancient vines at very high altitudes grown exclusively on granite bedrock and topsoil from many micro-parcels of local, indigenous grapes, like Brancelho (Brancellao), Borraçal (Caíño), Espadeiro, Vinhão (Sousón), and Pedral.

While it’s hard to sometimes connect wine regions using maps of specific countries because they seem to end at the borders, there are many that are just across the river from one another in Spain and Portugal, but between other countries there are often large separations of land around national borders. Here, these vineyards are within sight of the Rías Baixas subregion, Contado de Tea, and only less than twenty miles south, as the crow flies, from Ribeiro, the center of one of Spain’s most historic wine regions. Each of these regions share these grape varieties, and Zafirah is more closely related to Galician than to Portuguese reds. I have come to understand that in Portugal many of the young winegrowers look up to Constantino and greatly appreciate his Zafirah red. It’s stylistically by itself within his region. Most of the other reds here in Vinho Verde are dark and meaty (which I also love), but are made primarily with Sousón, a beast of a red, known here as Vinhão.

Thierry Richoux makes it impossible for me, no matter how distraught I am at certain times with certain French winegrowers, or nasty French drivers riding my butt like we’re in an unwanted game of Super Mario Cart, to make any generalizations often made about the French (which is done mostly by reductive people who’ve been rubbed the wrong way by them). I know no kinder, gentler and earnest man in the world than Thierry Richoux. I adore him, and sometimes I think this is mutual.

Every time I talk about, write about, think about, and finally drink wines from the Richoux family, I get excited. I have cellared a ton of them, but they are still not drunk without a proper special occasion. Thierry and his boys, Gavin and Félix, are in a league of their own in Irancy, a small, steep amphitheater that opens toward the west and is plastered with Pinot Noir grapevines grown on limestone and clay (the same basic soil type as Chablis, but not precisely a mirror of it), garnished with cherry trees. In the center sits one of France’s most ornate, ancient villages, with its narrow, adjoined, grayish-white limestone houses and sagging lichen-filled, dark orange roofs. Only two of his wines have finally arrived, and, believe it or not, both were ordered last summer! Others will be on their way this summer, including the magical 2016 Veaupessiot!

A very special arrival indeed is Richoux’s 2012 Irancy “Ode à Odette”. I’ve tasted this wine for years during its three-year élevage in new, 600l (demi-muids) French oak barrels before it was bottled and released last year. This is a once-in-a-lifetime bottling; it sounds absolutely crazy to be saying, right now, “I think the next one is scheduled to be the upcoming 2112 vintage.” At the time of the 2012 harvest, it had been a hundred years since Thierry Richoux’s grandmother, Odette, was born. She used to go to a particular parcel on the far northeastern corner of the amphitheater and work it by herself; can you imagine the meditative work during the years before iPhones or headphones and even battery-operated radios? I don’t even think I’m capable of that anymore without driving myself completely mad with too much inner monologue… Time to dedicate some time to mediate? Yeah, probably… This is the parcel Thierry has chosen for this very special wine. Through the moments of tasting in barrel, which I am sure I did at least six times, it always had a fabulous day, and this is what makes it so promising! While it’s young, at only ten years old, the new oak nuances are present but with some time open they get swallowed by the wine and—as embellishing as it sounds—a high-altitude, Vosne-Romanée-style Burgundy emerges. I know that sounds far-fetched, all things considered, but it carries that noble, voluptuous, clean and pure red fruit of those higher Vosne sites on rockier soil that stare down at some of the world’s most precious vineyards. Maybe it’s more of an emotional similarity than a directly comparable one, nevertheless I’m extraordinarily pleased that you will have an opportunity to snag a bottle, or two, of this wine. We imported just over three hundred bottles.

Richoux’s Crémant de Bourgogne is here now too. This has been a fan favorite since the first Richoux wines we imported ten years ago (man, has it been that long?) and we finally procured a good load of it. In the past we always needed to order well in advance because they mostly bottle for export markets by request. Made entirely of Pinot Noir, it’s a charmer, and if tasted blind you’d swear it was pink. There’s an anxious line of Richoux disciples queued up for this one, so let us know if you’re interested before it all gets snatched up.

We have another anticipated load from the family who introduced me to Thierry Richoux some years ago. The 2019 Collet 1er Crus are officially reloaded and ready to begin to circulate again. We have more of the Vieille Vignes, and the premier crus, Montmains, Vaillons, Forets, Mont de Milieu, Montée de Tonnerre, and Butteaux. It sure is hard to pick a favorite between them, but I’ve listed them in order from the most minerally to the most corpulent, with those in the center perhaps a tradeoff between these two particular characteristics. Now you only have to decide what shade you want/need over the next months. Just don’t forget that summer is coming soon, and it is tragic when there’s a shortage of Chablis during high Chablis-drinking season.

Justin Dutraive sure is making notable strides in his style. I think we all can acknowledge how difficult it’s been in Beaujolais to manage every vintage since 2015, where every year was a different variation of a mess. 2020 was no different. The weather was nuts, vacillating between intense heat and dryness, to cold and wet, then to monster heat and drought conditions. Well, at least the grape here is Gamay, one of the wine world’s jack-of-all-trades reds. Its versatility is enormous and almost unparalleled in the red grape world (in white, there are few that can match the versatility of Chenin Blanc and Riesling whose only restrictions are that they can’t be red!)… Gamay can take a solid knock to the face during the growing season and still smile through the glass at you. Justin managed very well this year and his overall style is much more elevated and nuanced than before. In 2019, there’s a nice uptick in overall quality and style, with a notable departure from denim and toward more lace. During my visit last summer, I was surprised, and openly admitted to the Dutraives, to the pride of his dad, Jean-Louis, that within the context of all the 2020 Dutraive family wines during that day I tasted (drank) with them, Justin’s were my favorites, and that’s never happened before between these two Dutraive ranges. I’m sure that since then, the Grand’Cour wine have, at the very least, stepped up.

During the second to last week of February (just as I started to write this newsletter), Justin sent me a note that our quantities of the 2021 wines are severely cut due to another year of tremendous losses. 2021 was the opposite of 2020, except the similarly low yields. It was a cold and dismal, mildew heaven that required an intense triage. 2020 is, in my opinion, Justin’s best year so far by a pretty good length. The three that are arriving are his Beaujolais-Villages “Les Bulands”, a wine that will not exist in 2021 because the entire harvest was lost. These vines are on a flat area with deep soils—prone to frost and greater mildew pressure, as it was in 2021, but ideal for the hot years, like 2020. Justin’s Beaujolais-Villages “Les Tours” on pure granite rock with almost no topsoil stands in opposition to Les Bulands. Les Tours is the kind of ankle-twisting vineyard where you must really watch your step because the granite bedrock outcrops here and there, camouflaged by shards of granite rocks scattered about. His Fleurie “La Madone” is on the famously steep hill below the chapel, La Madone, and is sundrenched and on spare soils. La Madone quantities are miniscule, so there won’t be much to go around.

The new releases of the top wines from Riecine have landed. I know 2016 is a hard follow, but every vintage has its merit and 2018 and 2017 are no exception. Like most of Europe (including Piedmont and Burgundy), 2017 was warmer around harvest and made for extremely clean picking. 2018 was also warm, but maybe a little readier in their youth than the 2017s?

2017 was a perfect year for La Gioia given this wine’s typical lead of a full red fruit spectrum that buoyed on its deep, earthy core. La Gioia is one of Tuscany’s seminal IGT successes with its inaugural 1982 vintage, designated as a “Vino da Tavola di Toscana.” While past iterations had 15% Merlot added to them, today they are composed entirely of Sangiovese since 2006 and is designed in the cellar for the long haul. Aged for thirty months in a mixture of new, second and third year 500-liter French oak barrels, it’s clearly not the same type of wine as any of Riecine’s wines because it’s notably more flamboyant and unapologetically full, decadent and loaded with flavor.

Continuing with Riecine’s less traditionally-styled wines is the Gambero Rosso “Tres Bicchieri” winner, 2018 Riecine di Riecine, a pure Sangiovese that transcends the appellation as a singular expression of the grape in the Chianti hills. It can test one’s notions of high-end, blue chip European wines—particularly those from Burgundy (minus all the new oak), and my first taste of the 2013 vintage was perplexing because the wine evoked the feeling of high-altitude red Burgundy from a shallow and rocky limestone and clay topsoil on limestone bedrock. It was supple but finely delineated with high-tension fruit, earth, mineral impressions and a sappy interior. Its beguiling aromas were delicate but effusive, and very Rousseau-esque, in a higher-altitude-sort-of-way (think Rouchottes, without the bludgeon of new oak upon first pulling the cork from that wiry but full beauty of the Côte d’Or). While similar to the Côte d’Or in some ways, this wine is grown at a much higher altitude of 450-500 meters—about 200 to 250 meters higher than most of the Côte d’Or’s grandest sites. To preserve the wine’s purity, and in opposition to La Gioia, it’s raised exclusively in concrete egg vats for three years, which serves this wine well; not all wines of pedigree can thrive so well raised solely in this neutral aging vessel. The vines planted in the early 1970s further its suppleness and complexity and concentrate its fresh red fruit characteristics. The 2018 is juicy and lip-smacking good, and I was surprised when we hit the bottom of a bottle over dinner long before the dinner was done.

After jumping from one opposing style to the next, we find ourselves with Riecine’s traditionally made, savory-over-fruity, 2018 Chianti Classico Riserva. It’s the third wine in a line of Riecine’s top-flight range (though soon there will be a fourth in the form of the new Chianti Classico classification, Gran Selezione) and clearly demonstrates the skill and versatility of Riecine’s wine director, Alessandro Campatelli. Harvested from vines ranging between the ages of twenty-five and forty years old, the wines are aged for twenty months in large, old oak barrels. With old vines grown on limestone and clay, this terroir imparts more roundness and a fuller mouthfeel than Riecine’s starting block Chianti Classico. At a tasting in Los Angeles with the most discerning palates from many of the city’s top Italian restaurant sommeliers and wine buyers, the merits of this wine, due to its more classical and expected style for a Riserva, were immediately evident and it was a true highlight with the more traditionally-minded Italian wine buyers. Indeed, it will age well in the cellar, but it can also be enjoyed early; just give it a little air before diving in and remember that it’s best drunk with the right meal—just like every traditionally-made Chianti Classico.

Faced with some recently arrived samples from a new project in Rioja with a lot of buzz around them, and so many thoughts swirling in my head, I began to write to encourage myself to be open to what sits in front of me. Countless times in my wine career (and my life), including the moment minutes ago that I began to cut the foils on these samples, I’ve come face to face with my own ignorance, and sometimes narrow mind, especially when it comes to wine. I confront myself and my predispositions more now than any other time in my life, and I’m sure (and hope) it’s only going to become more frequent. Change can be good, and many good things can pass by if we refuse to look outside our box.

I took on the French language about twelve years ago after dabbling in school and many years of trying to memorize phrasebook words and sentences on flights to French wine country. I understood the translations but not the actual roots of the words or grammatical structure, so any conversation beyond ordering food and securing lodging was impossible. Then, a few years ago, I focused on Italian during our short-lived stay in Campania. Once my wife and I discovered that Italy wasn’t our spot for the long haul, we went to Portugal. Portuguese has been brutal for me; it may as well be Martian. I think the seemingly insurmountable speed bump is a result of the void of Portuguese culture in the States compared to other European cultural influences. Spanish is my focus now, and I’m not surprised that it’s improving my Portuguese. It’s the easiest language I’ve studied, and it even reinforces what other foreign words still float in the dim lightbulb of my brain.

New styles and ideas with wine—especially twenty-five years in—are sometimes hard; as with the benefits of cultural immersion to learn a language, they sometimes have to be a little forced at first in order for any progress to be made. Our wine community can be brutally critical, especially when one is thought to be stuck in the style of wine they are open to, and I think you can tell when you run across someone who is set in their ways because the excitement is gone; the love lost. As I move forward in this wine life, I am as equally distraught by the enormity of it all, as much as I am excited and satisfied with where my path has led me and the things ahead that seem mostly clear.

Iberian wine appeared on my radar in 2013 when an old friend and quasi-mentor, the late Christopher Robles, recommended what was our single producer in Portugal for many years, Quinta do Ameal. These days I am tackling many new wine regions (for me) that seemed completely foreign in my recent past. In my early years when I had more energy to burn and healed faster, I had no problem sorting out big-hitter Spanish wine, like Priorat or Ribera del Duero. My most recent “old interests” remain, but the regions I fell deepest in love with are now bearing less resemblance to what they were with the stage of climate change even just a decade ago. Today it’s clearly advancing quicker, and it’s already worrisome that some wines are almost unrecognizable, not necessarily in the entirety of a terroir’s expression, but in their nuances developed through longer, cooler seasons, resulting in perhaps fresher fruits and more subtle things, with less concentration, and noticeably less alcohol.

I feel, at the very minimum, obliged to remain open because I see the burned-in impressions of the world’s historical regions slowly fading away from my palate memory: the taste of young, vibrant new vintages from blue chip regions and the excitement about their potential with longer cellar aging. In the past, wines from the most celebrated regions were designed for the longer game from the start, not to be sold and prematurely consumed during their formative years when the complexities in a more subtle form would take center stage.

I love low alcohol wines, crunchy fruit and zippy acidity; not only do they keep my mouth fresh, they keep my mind wound up, my energy and enthusiasm zooming and my heart pounding. They’re more invigorating, vibrating, goosebumping, and exciting, no? Bigger hitters are now saved for a once-in-a-while night, and most of the time Nebbiolo is the lead contender for my liver’s high-content alcohol allocation, and my I-know-but-I-don’t-care-if-I-feel-it-the-next-morning monthly limit. Andrea mostly opts out now when the label reads more than 13.5%. Like me, she likes to drink wine and doesn’t want to do it so sparingly. Now it’s a choice between two glasses of 12% or less, or a single glass of 13.5% or higher, for her. Sadly, I can hardly even get past the first glass of some of my old favorites that now clock in (and clock you) at a walloping 15.5-16.5%, when they used to be 13.5-14, tops; ok, maybe 14.5—but rarely! There is one producer I won’t mention by name (whose initials, M.G., may offer a small clue) who is the greatest recent loss for me in this way, and their older Nebbiolo-based wines remain in my private stash. While lamenting the absence of my in-home, Nebbiolo drinking companion, I’ve come to realize that there may be a third glass inside an epic Barolo or Barbaresco that I wouldn’t have gotten in the past!

I sure as hell won’t kick Vin Jaune off my list of annual needs, and many of you won’t either. But there’s a time and place for every wine and going bigger has become more of a special occasion because at forty-five (still young!), I can’t do 14% every night anymore. Simply from a sustainable perspective—if I want to continue to enjoy wine everyday—it must be lower alcohol on average, especially on weekdays. Of course, if they are big, they must also be balanced to enjoy—not so interested in big, wobbly wine caricatures.

We all have different calibrations, sensitivities and interests when it comes to our own definition of balance. Indeed, one size or style does not fit all. To find balance within low levels on the alcohol spectrum today is just as hard for those on the opposite end. We import many wines that hover around 10.5-12% alcohol that are often too intense for some but exciting and riveting for others like myself who aren’t deterred by vibrating acidity and freshness. (At the moment I’m actually drinking my daily quota of lemon water—a new experimental treatment for my skin challenges.) The same is true for the higher alcohol wines. If one decides to pick earlier in the season on the account of high alcohol concerns, to find balance there needs to be adjustments not only in the cellar work, but also with anticipation in the fields. All the world’s historical benchmark wine regions—with very few exceptions—are beginning to tip the scale too far in the wrong direction, and the growers are obviously not happy about it and are scrambling for answers. I imagine they feel stuck in a flavor/phenolic/balance calibration en masse by their neighbors and their region that makes it hard to make necessary concessions in favor of less alcohol and ripeness, while others on the opposite side of the spectrum have also gone too far—sounds like today’s politics! Winegrowers are doing their best to adapt quickly, but are struggling to keep pace with climate change.

I often contemplate whether or not traditionally famous wine regions will become a generational thing for the elders of the wine community that still hold tight to what used to be instead of a pivoting toward a sort of philosophical shift in greater favor to open-mindedness and continued learning and the acceptance of the ongoing and rapid evolution of our global winescape. But yesterday’s heroes should not be forgotten (or chastised by the alcohol police!) as they do their best to navigate solutions that can make the difference for their survival. Should we begin to accept (and mourn) that our favorites from Burgundy, Barolo, Barbaresco, Wachau, Mosel, and other places will never again be exactly like they were just ten years ago? Does this sound like climate change doom and gloom? Maybe… But I’m trying to look at what is happening in a more positive light, and as an importer looking for my own necessary solutions for the future.

What we’re seeing is newly emerging talents born into historically (at least in the last generations) second-rate regions (considered so mostly due to climatic limitations and/or locations far from big local markets and easy transport systems) who now have the potential to move into the top tiers of quality when in the past it only happened once every twenty years, not with enough frequency to gather attention and momentum. Another of climate change’s positive collateral effects is that it shakes up the system by opening opportunities for historical growers in colder regions who fought hard for generations to simply achieve ripeness with balance. Our new organic and biodynamic Champagne grower, Elise Dechannes, says that climate change makes it much easier for her and her neighbors to fully commit to these methods, when in the past there were much greater consequences for people using her practices. While climate change is indeed very disturbing and a real threat to humanity, today’s wine world seems more exciting than ever.

As I sink my teeth into Rioja and some other Spanish regions with higher alcohol levels than I usually gravitate toward, I’ve been surprised to find out that they may have a brighter future than many other historical high quality wine regions. Since we posted the new terroir map on Rioja and Navarra, solicitations from Rioja producers have poured in. There are many out there who want to break into the US market, and the Spanish wine critics are certainly rolling out some hefty (and sometimes overly generous scores) to get the region out of second gear. Once the growers figure out and accept what the upper tier of the fine wine market wants today, these areas will come alive with a clearer sense of what to do, and they may stir some serious waves. Today, there are only a few mostly small-scale producers who are changing the game in some of these areas, but their success will pave the way for those who are worried that they might be stepping out of line; I’ve heard many stories about members of the new generation making almost unnoticeable changes in family cellars, on the down-low, so as not to upset their families, those who did the groundwork for them to have the opportunities they have today. Obviously, I’m excited about these wine regions and the growers who want to reach beyond the historically self-imposed confines that many believe exist.

Two hours later and a mess of red wine on my table…

I don’t know how Tim Atkin does what he does. I certainly couldn’t. In his report, (along with the fantastic section, “The Ten Things you Need to Know About Rioja 2022”), there are 132 pages of tasting notes with about six to eight wines reviewed on each page, mostly with in-depth notes—not quite John Gilman-level depth, but still thorough. Of the wines I just tasted, three of them were awarded 94, 95 and 96 points, and Atkin’s notes are detailed and enthusiastic about them all. The wines are clearly well made, though I think they’re tailored for a different generation than my own. The extraction is gentle, but the ripeness is still bordering on too much. All of them have a blockade of that slightly pungent reduction/new oak characteristic—that too many days-old, raw, oxidized ground-beef-in-butcher-paper smell, and the burdensome oak tannin to match. The best scenario for me is to write to the producer to have them give me the “hard news” that they’ve already found a new importer—letting me off the hook easily… Indeed, Rioja as a general region has a long way to go (at least for my taste in wine), but when it gets there, it’s going to be exciting. The region has too much going for it to prevent its advancement, even in the face of climate change.