We used to look forward to summer, but now we can’t wait until it’s over. Summer used to be much more fun, but these days it’s a game of hide and seek shade. Where we are in southwestern Europe is not prepared for this type of heat. Most of the buildings and houses in historical areas (without massive new apartment buildings) aren’t equipped with air conditioning window units because most are constructed with side-hinge windows instead of the sliding kind. Sure, mobile units are everywhere, but one must be an architectural engineer or builder to install them into a swinging window or door, and even then, they are obnoxiously loud and produce as much heat from the tubing inside the room from the unit to the window that makes them a disaster in efficiency. We love living in Europe, but my wife and I admit that we miss the simple luxuries living in the US, including but not limited to having cooler rooms in the summer.

This year has been a roaster over here, with three (maybe four) different major heat waves in Iberia in about six weeks. Most of Europe has experienced the same, and as one would expect, with the drought has come major water shortages. Occasionally a desert-like deluge blows in with strong winds, with rare thunderstorms and lightning that showed up in late July and August. We were passing through Rioja in the first week of August and as we parked at our hotel the temperature and ambiance changed dramatically in no time. It was a relentless 100°F until a system moved in from the north and in a few minutes it was pouring rain and the temperature dropped into the 60s. In other regions, like Piemonte, which is having one of its driest seasons on record, they finally got temporary relief with the arrival of some water, but the temperature hasn’t wavered.

Despite the dire situation for many global wine regions, this year in much of Europe looks to be a bumper crop—that is, if nothing crazy happens in the last moments before harvest! Most of the year’s losses are a result of dried out and burned sections of clusters and clusters entirely exposed to the sun, or some small issue with powdery mildew (though not much downy mildew this year because it’s reliant on the moisture that’s been so lacking). Pablo Soldavini, an Argentine winegrower in Galicia who has many projects brewing, like Adega Saíñas and his new eponymous label to come later this year, says than another factor is that many days in Ribeira Sacra got above 40°C (104°F), resulting in smaller berries and a shutdown of the plant, which will delay the harvest. With so many recent hot years with low yields, it will be interesting to see if or how these higher yields can counter the heat and normalize the balance of the wines—whatever normal even is these days. We should at least expect lower alcohol levels than we’ve had in most recent years.

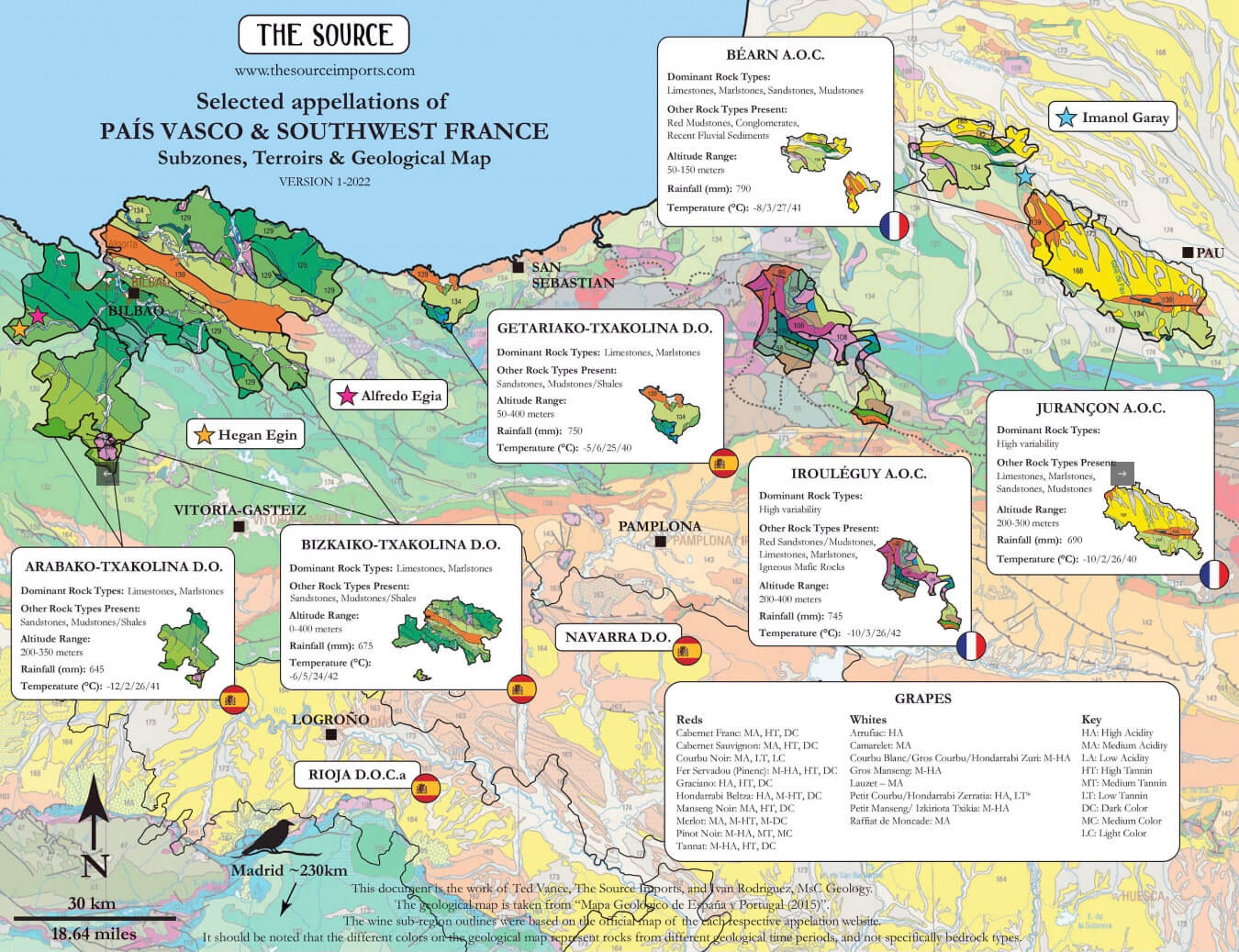

We have a new map this month. There are quite a few more in the queue, but I’m behind on my must-dos and these things tend to end up at the bottom of the priority list. This month it’s a unique combination of appellations in Spanish and French Basque country and some neighboring Southwest France appellations. Imanol Garay, a grower we work with, jumps the borders each year to play around, sometimes resulting in wines labeled as generic European wine. There are a lot of grapes in common in this part of Spain and France, but sometimes quite different geological, topographical and climatic settings between them. It’s easy to overlook that where national borders are does not signify an end to their commonality. I hope you enjoy the map!

A list of the Summer Euro Tour Top 5 Wines from our staff is at the bottom of our newsletter. I highly recommend taking note of their picks. They know our wines well and the measure of what truly stands out. Don’t miss it!

2019-2021 Salnés Vintages

Adrián Guerra, a partner in a new Albariño project in Salnés, Xesteiriña, and a former partner of one of the top drinking spots in all of Galicia, Bagos, in Pontevedra, offered an explanation of these three vintages. For our purposes with regard to whites, we’ll just cover what happened with Albariño. As for the reds, given that the red grapes of the area need higher temperatures than more “classical” years to develop balanced tannin and acidity, one can speculate their general disposition on ripeness. The reds from 2019 and 2020 will be very good. We expect the same for the 2021 reds, but they’ll likely be even more racy and intense than those from riper years, like 2017 through 2020.

Adrián says that Salnés has been impacted less by climatic temperature increases than other areas and that the 2019, 2020 and 2021 vintages were all quite similar throughout the growing season. Where vineyards are as close to the Atlantic as those of Salnés, the influence of temperature extremes is less drastic than those further inland in places like the Rías Baixas subzones, Condado de Tea and Ribeira do Ulla, and many more so than other Atlantic-influenced interior Galician appellations, like Ribeiro and even parts of Ribeira Sacra. A lot of the vintage variation in Salnés is largely influenced by mildew pressure and rain. Those losses greatly affect yields, which also influences the final phenolic ripeness of the grapes. 2019 and 2020 are slightly more similar to each other than they are to 2021. Both of the former vintages allowed most winegrowers to take their time harvesting as they wanted. The alcohol level of Albariño in these two years hovers around and just above 13%. Adrián also pointed out that critics speak of these two vintages as warmer seasons, but when compared to years like 2017 and 2018, they are much fresher.

2021 was similar regarding annual temperatures and rainfall but was marked by lower alcohol levels closer to 12%. Adrián credits this more “classic” Salnés Albariño with lower alcohol in this similarly dry season to 2019 and 2020 to rains just prior to harvest. He believes the slightly higher yield and the rains restored a certain balance to the fruit.

Things are coming along for us in Rías Baixas these days and the addition of the micro-producer, Xesteiriña, will be yet another superstar in this appellation that we’ve added to our collection. Xesteiriña is in Salnés and comes from a single vineyard just west of Portonovo, very close to the Atlantic. The project and property is owned and operated by the extremely sharp and thoughtful José Manuel Dominguez, an Agricultural Engineer who comes from three generations of winegrowers in Salnés. The vineyard is a unique geological location largely composed of granodiorite and what may be some transitional materials similar to gneiss. In any case, the rocks are hard as heck, and the vineyard topsoil is incredibly spare, composed almost entirely of organic matter.

José Manuel’s approach in the vineyard is one of caution and respect for the ecological environment. Organic methods guide his work, despite being so close to the ocean—a hostile environment for mildew and vine diseases. The vineyard is surrounded by forests of mostly indigenous Galician trees that are rare in these parts, and José Manuel wants to keep them for the biodiversity of the vineyard.

Raised in a combination of old oak barrels and stainless steel, the 2020 Xesteiriña Albariño’s core is strong, dense and mineral, like two bottles of wine crammed into one. While its body is full and seemingly ready to supernova any moment, it remains serene and focused, vibrating with what feels like the life force of the rock and the crashing waves not too far from its birthplace. The lab numbers are impressive at 12.7° alcohol, pH of 2.92 and ta of 10mg/L, and will provide some insight on how this wine strikes and rests in the palate. It was raised in 70% stainless steel and 30% older French oak barrels over ten months. Xesteiriña has few bottles for world export, and they are worth getting your hands on. Only twenty cases were imported to the US.

As often happens while he’s on vacation or touring in Spain, our Southern California superstar salesman, JD Plotnick, fires text messages to me of wines he’s tasting as he moves through his favorite European country. One of the most recent was a photo of the Albariño by Pedro Méndez, cousin of local viticultural legend, Rodrigo Méndez. Luckily for us, he had not yet chosen his US importer, though there were many in line. After a short drive to Rías Baixas from our Portuguese apartment in Ponte de Lima, I had lunch with Pedro at Casa Aurora, owned by our mutual friend, Miguel Anxo Besada, also the owner of the famous local wine spot in Portonovo, A Curva.

Like Miguel, Pedro is in the restaurant business. His family owns a small restaurant in Meaño, in the Salnés subzone of Galicia’s Rías Baixas. During the summer tourist season, their restaurant, A Casa Pequeña, keeps Pedro completely busy, and attends to bare necessities in the vineyards. The rest of the year he is solely focused on his vines and the cellar.

After our lunch we had a tour of his vineyards where the highlight was the ancient, pre-phylloxera Albariño vines that are nearly two-hundred years old and look more like trees than vines. These ancient plants make up the composition of, As Abeleiras, the wine JD first had and a wine that floored me the first time I drank a bottle with Pedro. It’s a sort of Raveneau-esque Albariño in body and structure but with a pure citrusy, salty, minerally, high acidity power that only Albariño possesses. His entry-level Albariño doesn’t list the grape on the label and is aptly called Sen Etiqueta (without label). Its grapes are harvested from his family’s other vineyards scattered throughout Rías Baixas, mainly in Meaño, a three or four mile flight from the Atlantic. It’s snappy, minerally, pure and a fabulous deal for the quality. Pedro is young, talented and extremely humble and hospitable. I’m sure he’ll soon become one of the most recognized names in Rías Baixas.

While it seems like we’ve already worked together for a decade because we spend so much time together, it’s only our third and fourth vintages working with Manuel (Chicho) Moldes. Rías Baixas is a special place, and Chicho is right in the middle of its movement onto the world’s wine stage. Chicho is a busy man with no time for English, travel or kids; he only has time for wine, his wife, Sylvia, and his local friends and outsiders like us who visit regularly. I’ve pried him out of his shell on occasion to do some traveling through wine country to Chablis and the Loire Valley, but he otherwise remains laser focused on his gradual expansion. This year he completed a new winery next to the garage where he crafted all his wines prior to the 2021 harvest, and he continues to grab little parcels here and there in Rias Baixas; in all, he has more than fifty miniscule plots now, many of which are the size of a large backyard garden.

Arriving this month is his 2020 Albariño “Afelio,” a wine grown on a collective of dozens of parcels on granite bedrock and topsoil (with only a tiny amount of schist, if any at all). The grains of soil vary highly from fine granite sand to gravel, some with a shallower depth and others with much deeper topsoil. This makes for a good mixture of palate textures and balance of muscularity and finesse, and an all-around great representation of Salnés Albariño. With the Afelio bottling, he started with some partial aging in old oak barrels but he’s inching closer and closer to using almost all older barrels. This vintage spent its first months in stainless steel and its last in old barrels.

The 2020 Albariño “A Capela de Aios” will always be in short supply and high demand. Grown on ancient and nearly fully decomposed schist, with the rock formations on the upper sections of bedrock completely rotted in place, and it’s aged entirely in 500l-600l old French oak barrels to complement its fuller body than the crisper and tighter Afelio, this wine has greater depth and more complexity and perhaps a slightly more rounded character than the next wine, Peai.

The 2020 Albariño “Peai,” (pronounced like P.I.) is the newest in Chicho’s range. Grown on a shallow topsoil of decomposed schist derived from the hard schist bedrock below, it’s the most muscular and angular in the range. Big textures and metallic/mineral notes dominate the palate, yet the nose is brightened with delicately salty sea spray, sweeter white and yellow citrus, and the cleansing petrichor of a fresh rain in a rocky countryside.

Already gathering a cult-like following, the 2020 Albariño “As Dunas” is grown entirely in extremely fine schist sand, ground down by ocean waves when it was a beach millions of years ago. This is the most elegantly powerful Albariño in the range, displaying an incredible duality of finer, more nuanced points delivered with tremendous thrust, energy and structure. This group of vineyard parcels was divided between Chicho, Raúl Perez and Rodrigo Méndez (again, the cousin of Pedro, one of our new producers)—the latter two, local luminaries of the Galician wine trade.

Chicho’s two arriving red wines have diametrically opposed characteristics and are from different regions, with 2019 Acios Mouros hailing from Rías Baixas, and 2019 Lentura from Bierzo. Only a three-hour drive away, they are completely different terroirs in every way (except that they share acidic soils), from dramatically different climates, exposures and surrounding ecosystems. The landscape moves from Rías Baixas’ rainy, humid, and wet Atlantic influence at low altitudes, to Bierzo’s Mediterranean/continental climate of snowy winters and boiling summers. Bierzo is arid and barren with vines grown at altitudes as high as 1000m.

Acios Mouros is tensely loaded with an acidic, goose-bumping freshness. It’s grown on mostly granite soils close to the Atlantic and raised in old 500l-600l French oak barrels for about a year before bottling. Fermented and aged separately, it is a blend of 70% Caiño Redondo (the high acid, energy, red fruits, flowers, and light balsamic notes), 15% Espadeiro (the rustic, floral and lightly fruity medium-bodied contribution), and 15% Loureiro Tinto (the beast with all the black hues and wild notes). The Bierzo is a blend of 60% Garnacha Tintorera (dark red and black color, power, acid, juiciness) and Mencía (elegant, body-softening, red fruits and flowers). Lentura is notably fleshier and richer than Acios Mouros, a wiry, sharp and minerally wine. Lentura comes from the vineyards of one of his dear friends, José Antonio García. It’s a mixture of grapes from vines on the lower rolling hill areas on deeper white and red topsoil mixed with river cobbles, and vineyards higher up on the extremely steep and slippery slate hillside of Corullón.

Our Rías Baixas game is now equal to that of our Ribeiro. However, our Ribeiro group is very special and with a unique array of wines between El Paraguas, Cume do Avia and Augelavada. Cume do Avia’s wine will come later this year, but in the meantime the other two have wines arriving this month—or at least we hope so, depending on supply-chain issues…

Marcial Pita and Felicísimo Pereira continue their ascent to some of the higher levels of Treixadura wines from Ribeiro, the spiritual and historical center of Galician wines. Most of their vineyards are granite/granodiorite, with one specific parcel on schist. The style is, and I apologize in advance for this overused comparison, more Burgundian than most whites from Galicia. It’s not the nuances that match Burgundy, but rather the corpulence and broader palate weight of the wines. Aromatically, they are nearly everything but Burgundian and express their terroirs with great clarity, led with honeyed citrus blossoms, saltiness and fresh white fruits like yellow apple and pear.

Ribeiro’s ace up the sleeve on white wine is Treixadura, a grape that thrives better here than anywhere else. In the right hands (like Paraguas’), it appears to have the chops to stand tall in complexity within the world of more full-bodied white wines. Their first wine in the range, El Paraguas “Atlántico,” is roughly 92% Treixadura and 8% Albariño—the latter addition to improve the wine’s acidity levels, mineral freshness and a citrusy zing. Made from a blend of their three different vineyards, one on schist and two on granite, it’s a powerhouse of quality and breed. Like all of their wines, it’s aged in 600l French oak barrels, a clever choice for this variety, and perhaps my favorite non-foudre-sized wood barrels. Although the difference between a 500l and 600l barrel seems negligible, it’s the stave thickness between them that makes the difference. The 600l barrel is typically about 30% thicker, which greatly influences the oxygen intake ideal for Treixadura, a variety in need of slower maturation in a tighter grain if aged in wood to preserve its finer nuances.

La Sombrilla is grown entirely on schist, and this rock and soil type tends to make fuller and slightly more expansive wines in the palate, with metal and mineral notes that are deeper in the back palate than granite’s commonly front-loaded power. They chose to age La Sombrilla in some of the newer barrels (along with older ones too) because it wears it better than wines from granite soils—an opinion I share. It is not their objective to work with much new wood, but they prefer to buy new instead of used barrels. La Sombrilla needs time once open to express its best traits. There is always a little nuance of newer oak upon opening (as it is with almost every serious white Burgundy outside of Chablis) and with a little patience it will begin to reveal its full hand.

Iago Garrido continues to lead a singular path in Ribeiro with his game-changing, flor-influenced wines. Iago explains that in the past flor was part of Ribeiro’s success, and that in Ribeiro, wine was often sold as full barrels to restaurants or for transport. There was surely a thriving BYO bottle (to fill) private-customer base who took directly from the cask as well. If flor yeast didn’t develop its protective layer in these large barrels as wine was slowly drawn from them, it wouldn’t last—it was essential for preservation at that time. So, if you see it from that perspective, Iago’s wines may be some of the most “traditional” of the entire region!

Everything Iago makes has its own personality. Most, if not all the wines, are aged in a combination of larger old barrels (300l/500l/600l) and amphoras under flor yeast. Even if one of the particular wines was not under flor, it still carries the aromatic specificity of a cellar where flor is present, which adds nuanced complexity.

The 2020 Mercenario Blanco is a mix of Treixadura, Albariño, Godello and Palomino. All grapes are sourced from various spots inside of Ribeiro on the banks of its main tributaries, Avia, Arnoia, and Miño. The average vine age ranges between 15 and 50 years and is on a mixture of igneous (granites/granodiorites) and metamorphic bedrock (Iago suspects mostly gneiss) with clay-rich topsoil. It’s aged in very old 500l and 600l barrels, glass carboys and amphora vats. This is the lightest white in the range and sometimes opens quietly but always picks up momentum with each passing minute, evolving very well for days after opening. 300 cases are produced.

The flagship white wine, 2019 Ollos de Roque, is made entirely of Treixadura from the biodynamically-farmed, granitic Augalevada vineyard, tucked back behind the historic San Clodio monastery and the property of the fazenda. This is the wine that guided Iago into his flor yeast life by accident in 2014 when he buried an amphora in his vineyard that naturally developed a flor covering. At first he was mortified, but thinking it was a mistake to throw it out, with some time in bottle it developed a profound quality. Today it is indeed the most intense wine in the range, despite its very young vines, and delivers a beautiful balance of restrained power and elegance. The nuances of flor are present but folded in as to not overpower the terroir and Treixadura’s subtle qualities. It’s aged in a mixture of 840l, 500l and 330l old wood barrels and 400l amphora vats. 120 cases were produced.

The first red in his range is the 2020 Mercenario Tinto, a blend of the powerhouse local varieties (from most elegant and fruity to the most rustic with deeper color) Brancellao, Caiño Longo, Espadeiro, and Sousón. Iago works with a plethora of small parcels scattered around Arnoia, Avia and Miño river valleys on mostly granitic soils with vines between 15 and 30 years old. With a very light and almost no-touch approach, the fermentations in these various vats lasted between 32 and 45 days. 80% of the wines are aged in 500l barrels and one 400l amphora vat for ten months. This is a very special wine indeed for Iago and it brings great pleasure to those seeking lower alcohol reds with depth and texture while maintaining interesting aromatic components tucked in behind its beautiful red fruits. My wife and I have consumed at least 30 bottles of the 2018 vintage (likely closer to 40, but I shy from possible hyperbole…). The 2019 was also very good but was more of an experimental vintage for Iago. In 2020 there was more stem inclusion, which made a fair exchange of fruitiness for more upfront earthy, savory, spicy and deep mineral notes. 300 cases were produced.

2019 marked the first vintage of Iago’s Mercenario Tinto Selección de Añada, something I requested he make when we were tasting the 2018 reds out of barrel. The 2018 was so utterly special and remains one of the most distinct barrel tasting moments of my career as a wine importer. There was a single 500l barrel out of three that year that completely rocked me. The other two were also impressive, but the third was like a long lost relative of Pierre Overnoy’s red wines—big praise I know, but worthy of the comparison. It was so special that I wanted the world to know it and taste it, but he blended it with the others to make an extraordinary wine in any case. I can still taste that single barrel folded in with the other two in the 2018 Tinto. 2019 was a very good first Selección de Añada, but, in my opinion (and I believe in the opinion of Iago as well), it didn’t reach the same level it didn’t reach the same level as the 2018 Mercenario Tinto.

The 2020 version has a different agenda than the 2018 Tinto and the two 2019 Tintos. This year, he’s going for a more “meaty” style than in the past—likely an inspiration from the style of wines of two of his Galician heroes and local icons, Luís Anxo Rodríguez (Ribeiro) and José Luis Matteo (Monterrei). It comes from 15–40-year-old vineyards in the Arnoia and Avia valleys on granitic soil. In the cellar it was macerated for 45 days and then aged for a year in a 600l and a 500l barrel. 120 cases were produced.

Andrea Picchioni is a historic producer of great distinction. There is no better winegrower in the world than the one who is energized by his vineyards, in love with them, and wants to live in them and learn from them, instead of being the one to teach them what he thinks he knows. This is Andrea Picchioni, a man on his own path, inspired by one of Italy’s iconic vignaioli, the late Lino Maga, second to none in the Oltrepò Pavese, a man who was Andrea’s spiritual leader, mentor and friend. Picchioni is the Mega to Lino’s Maga, and since they were so close I am sure that Lino felt the same. We had the great pleasure of meeting Lino the year before his passing and he graciously invited us to visit again. Lino and Andrea’s bromance was on full display, which led to a series of fabulous photos snapped by our team on the visit. What a special memory.

Andrea works in the home of the original Buttafuoco vineyards in the Solinga Valley, with only the kind and joyful human war tank, Franco Pellegrini, to keep him company (a man responsible for giving me the most rustic wine and cheese I can recall daring to put in my mouth). Andrea is a solitary vignaiolo with no benchmark other than that of Lino’s Barbarcarlo, to which his equally original wines overflow with tremendous depth and unapologetically full-flavored richness. Andrea grows his grapes on some of the steepest unterraced vineyards in Italy, with vines that run from top to bottom rather than side to side. The calcareous components of his vineyard topsoil keep the conglomerate bedrock cobbles below cemented into place so these vineyards don’t slide right down these treacherous hills and fill the steeply V-shaped ravine below.

During our summer trip this year, Tyler Kavanaugh, our San Diego company representative, fell even more in love with Andrea’s wines. We were treated to a series of older vintages of Riva Bianca and Rosso d’Asia, some ten years old and others back to the 90s, all of which seemed like they’d hardly aged at all in the bottle except for the fact that the x-factors were more clearly defined.

Picchioni’s unabashed style of wine is committed to the historical Buttafuoco blend of Barbera, Croatina and Ughetta di Canneto (a regional Vespolina biotype). He also has some Vivace wines and we’ve added one to our shipping container. The 2021 Bonarda dell’Oltrepò Pavese is a fabulous, dark and full-flavored, semi-sparkling red. Made entirely of Bonarda (Croatina), it’s fermented on the skins (fully destemmed) for four to five days, then pressed and racked into autoclaves where it continues its fermentation under pressure. There are few wines so perfect in the world for cured meats and fatty animal cuts than a sparkling, cold red wine from the many areas of Lombardia and Emilia-Romagna. This wine is a true highlight compared to most others that are mass produced under chemical farming. Here at Picchioni, it’s organic all the way and the wines feel more alive than any bubbly Italian red I can remember.

Into the more serious range of still red wines we find Andrea’s two big hitters, 2018 Rosso d’Asia & 2018 Riva Bianca. These two powerhouses come from nearly adjacent vineyard rows but are composed of a different grape blend. Rosso d’Asia is 90% Croatina and 10% Barbera, and the Riva Bianca plays within the rules of the Buttafuoco dell’Oltrepò Pavese appellation with a blend of Croatina, Barbera and Ughetta di Canneto, and Andrea doesn’t keep track of the exact proportions of these grapes. Rosso d’Asia is macerated on skins for more than 60 days, while Riva Bianca’s maceration lasts between 90 and 120 days—a long time in each case! Both are aged in large wood vats for two years before bottling.

Trying to describe the flood of generous nuances from these two wines would take an entire page of new notes written every thirty minutes as they evolve after opening. In general, the Rosso d’Asia could be described as the straighter, darker, more peppery, brooding wine. Its muscle, spice, acidity and tannin are on full display and seamlessly woven together. Riva Bianca could be described as having a greater range of x-factors—similar to Lino Maga’s wines in spirit, but much more precise and cleanly crafted. I’m confident that the bacterially related “funk” in Maga’s wines was deliberate, and likely (based on his polarizing reputation) an attempt to rock the boat of enological correctness, perception of hygiene, bacteria’s role in authenticating a regional wine’s taste, the homogenization of the wine world, and the disruption of cultural histories and regional tastes. But of course, this is just speculation on my part.

On the other hand, his student and friend, Andrea, is more rooted in craft along with his immense respect for nature, which is on full display in his organically farmed vineyards. Nature is truly Andrea’s guide (which is evident in each of his wines), but he respects the craft and works to fine tune it without any loss of authenticity. His wines display a clear intent to reveal their highest highs without straying too far off into the bacterial wine vortex. If there was one rogue in the bunch that forages deeper into the world of bacteria, if only as a supporting nuance, Riva Bianca would be the wine with that wanderlust. This is why it’s also his most spellbinding wine.

Most of us get one coming out party in our life (I think…) and 2019 will be the year for Dave. Since our first tastes of any of his 2019 Nebbiolo wines out of barrel, we knew they would be more than just special; they were going to be a breakthrough. From the Nebbiolo d’Alba all the way to his top Barbaresco crus, there is magic in the entire line, and he’s already made some head turners, especially in 2016. However, there is almost no chance that any wines prior to 2019 will rival this banner year.

A description that seems to be finding its way around the wine community to best describe what sets Barbaresco in 2019 apart from other great vintages is elegance. For such a profound vintage with tremendous depth and guts, this is one factor that may help it to rise in stature higher than 2016 and 2010. 2019 has everything, and for this taster, there is no greater achievement for a wine with “everything” than to be led by gracefulness, even if it’s just slightly ahead of its strength and depth.

I asked Dave to give us a rundown of the five most recent vintages in Barbaresco. Many people, including the critics (and even I) tend to lump Barolo and Barbaresco into the same sort of vintage bullet points. Indeed, they have more similarities than differences, but as slight as they may be sometimes, the subtleties separate wines; the separation of true greatness from excellence is a game of nuances from one season to the next. Not necessarily regarding temperatures, but rather the timeliness of rains, hails and frosts, and other things that can dramatically change the yield and health of a season particularly built to develop those nuances. If you lose to frost, it changes the grapes immensely; if it rains in one place and not the other, you have wines of different fruit components, alcohol levels and structure; depending on the time of year, hail can ruin an entire field, while the one next to it remains untouched. In Piemonte, it’s all the luck of the draw.

2017 was warm. A frost in July lowered the yields but the resulting wines had good density and mild structure making them approachable early. I harvested all of my Nebbiolo grapes before the 22nd of September.

2018 had a late snow in March, which was a welcome delay for the vegetative cycle, thus extending the maturation period to later in the season. Some rainfall in September and October delayed the harvest, but less so in Barbaresco than Barolo. The wines tend to have a delayed expression. They’re also tight in tannic structure but with prettiness and a lot of elegant fruit. I like this vintage a lot. All of my Nebbiolo was harvested in early October.

2019 was a perfect season with ideal weather. The ripening was slow and progressive—Nebbiolo’s calling card. They are wines of elegance and finesse on the nose with great supporting structure and acidity for long aging typical of great vintages. For me, it’s the best in the last decade. I harvested my Nebbiolos just before mid-October.

2020 was another warmer season, but not as warm as 2017. The wines are very approachable with softer tannins. The tannins are also not as dense as 2017 and are more in the direction of great Pinot Noir and its supple nature.

2021’s slow ripening season is similar to 2019. Cool nights and heavy rainfall came in early September, which brought a welcome extension of the season where Nebbiolo was picked up until mid-October. The wines have great structure but maybe more density than 2019. At this point, I think it’s an exceptional year but I don’t think it will reach the heights of 2019. However, it’s too early to say.

All of the Nebbiolo-based wines are made the same except for their time spent in barrel. Everything is destemmed, the extractions are gentle and sparing with typically one punch down every other day, and only pumped over if needed. Fermentation time can run from two weeks to two months, and is made without temperature control. “Tannins need to be managed in the vineyard, not the cellar, so if they take a long time, I’m not worried about over-extracting them because they were picked when the seeds were ripe.” The first sulfite addition is made after malolactic fermentation is completed. All are aged in 300-liter, old-French-oak barrels with a minimum of ten years of use. This is interesting to note because the wines have a woodsy quality that appears to be an influence of younger barrels, but Dave explained that sometimes Nebbiolo and Barbera naturally express this characteristic, and it’s hard to say why; perhaps it’s somehow organoleptically linked to their ingrained balsamic-like nuances. The use of smaller, more-porous barrels instead of larger botte would increase their oxygen and could accentuate this characteristic. The Langhe Nebbiolo is aged for 13-14 months (as were the Nebbiolo d’Alba wines before the 2020 vintage) and the Barbarescos for 26 months. He does no fining or filtration.

Dave’s 2020 Langhe Nebbiolo, formerly labeled a Nebbiolo d’Alba, is a blend of 90% Roero Nebbiolo inside the Nebbiolo d’Alba appellation, and 10% from young vines in Barbaresco territory around Neive. This 10% addition from Langhe, outside of the Nebbiolo d’Alba appellation, forced his hand in using that appellation instead of Nebbiolo d’Alba. The tannins here are a little softer in profile and require less aging in wood to reach a good evolution. The result of the shorter aging with Roero’s much sandier soils makes for an upfront, delicious, red-fruited Nebbiolo with gentle leathery rustic notes.

The starting Barbaresco “Recta Pete,” (a name taken from Dave’s historical Scottish family clan name that means Shoot Straight) is sourced from the younger vines of three different powerhouse cru sites and is a blend of roughly 55% Roncaglie, 25% Starderi and 20% Ronchi—the latter likely to be bottled in 2022 as its own cru. The marriage of these three exceptional sites with their variations in temperature, exposure and soil, along with the younger vines makes for a wine with great energy and earlier approachability. But all of Dave’s 2019s are quite approachable early on due to their elegance.

The outlier between the three crus, Starderi is the warmest of Dave’s Barbaresco sites and has the highest percentage of sand mixed in with calcareous marls. He describes these influences on the wine as driving it toward the expression of red fruits, like strawberry, raspberry, and cherry. The tannins from these 45-year-old vines are finer than the other two crus in a sort of chalky Pinot Noir way, which he also attributes to the sandy soils.

Dave views Faset as a quintessential classic central-zone Barbaresco grown on middle-aged vines (35 years or so) with a stronger clay component to the soil and a direct south-facing exposition. It’s the richest in pallet weight of the three and has a stronger tannin profile when compared to Starderi. There is less of the red and lighter fruits as they have moved further into darker, perhaps more developed maturation with more layers like plum and fresh, dark fig.

Dave feels that Roncaglie has the best of both Starderi and Faset. The tannic structure is like Faset and its similar clay soils which also increase its core density. The fruit’s profile flaunts hallmark Nebbiolo notes with violets, cherries and rose petals, all of which can be attributed to it being in a cooler position than Faset. Dave buys his Roncaglie fruit from the Colla family from a variety of different spots and vine ages. In my tasting of these three wines from Dave, Roncaglie is the standout in pure breed and finds the next level of regality. It’s one of the truly epic crus of Barbaresco and it’s a treat to see a different but equally thrilling rendition of it alongside the Collas’ 2019 Roncaglie masterpiece.

and Victoria (Vance) Diggs.

I promptly got Covid on the Iberian trip this summer and was ejected from the tour, so I missed almost all the visits. For this reason, there is less commentary from me for their choices because I wasn’t there to taste these new wines! Believe me, I was jealous…

We start with some input from our own Leigh Ready, a Santa Barbarian deeply in touch with nature. She spent a lot of time in the restaurant business and selling wines for import companies, but she also worked many years for an organic produce farm. Leigh’s top five Iberian wines were the Spanish wines Javier Arizcuren’s 2021 Rioja Solo Garnacha Anfora (grown at 550m on calcareous soils), Pedro Méndez’s 2019 Viruxe, a rare and unusually fabulous Salnés Mencía (maybe we’ll get an allocation with the 2021 vintage). In Portugal, her favorites were the Constantino Ramos 2019 Afluente Alvarinho grown in Monção y Melgaço’s higher altitude areas around 300m (most of Monção is quite low in altitude by comparison), and finally from our two producers in the arid and high altitude (600-650m) Trás-os-Montes, 2021 Menina d’uva Rosé and 2021 Arribas Wine Company Rosé.

Hadley Kemp, one of the newest to our team is based in San Francisco. Also a former restaurant pro as a General Manager and Sommelier, she was well-trained on wine and is one of the few of her generation (Millennial) afforded the opportunity to work with extensive wine lists loaded to the gills with the world’s greatest blue-chip producers. Despite this special experience, most of her choices were perhaps less “classical” in style, an indicator that she is not stuck on the past but loving what today and the future have to offer! She also chose the Javier Arizcuren Sol Garnacha Anfora, Constantino Ramos’ Afluente Alvarinho, and Arribas Wine Company’s Rosé. Her other favorites were Constantino Ramos’ 2021 Zafirah, a blend of Vinho Verde red grapes, and Pedro Méndez’s 2021 Albariño Sen Etiqueta (100% monovarietal but not labeled as an Albariño) from Rías Baixas’ Salnés area, which is arriving this month!

JD Plotnick and Tyler Kavanaugh, two of our Southern California salespeople, joined me on a tour through Italy and Germany. JD also started the trip with me in Austria, so Tyler’s top five won’t include Austrian wines. I was Covid-free through this trip, unlike the Iberian leg, and was there to watch their emotional reactions to the wines, which made it a little easier to guess what their top picks would be.

JD Plotnick works with us in Los Angeles. A former cook at one of Chicago’s great restaurants, Schwa, and a classically-trained musician, his relationship to wine closely relates to these precisely tuned and harmonious arts. His list included four wines that also made my top 15 list posted in our July 2022 Newsletter. Bookending the trips through the German-speaking countries, he included Veyder-Malberg’s 2021 Riesling Bruck, a truly spectacular wine from one of the wine world’s greatest alchemists from one of the best years known in the region. Next is Katharina Wechsler with her wine labeled, 2021 K. Wechsler Riesling Schweisströpfchen. This wine borders between Spätlese and Kabinett (52g/L residual sugar) and is grown in the great limestone cru, Kirchspiel, in one of its warmer sections. (It could have easily made my top 15 list too, but I already chose a different wine from Wechsler—check out Tyler’s choices to see which one!) Just across the border of Austria and into Italy’s Südtirol, the young Martin Ramoser’s 2020 Fliederhof Sant Magdelener “Gaia,” made entirely of Schiava, also made my top 15 list (posted in our July Newsletter). What a special wine! A super breakthrough performance that will arrive in minuscule quantities (only four cases!) this fall. Poderi Colla’s 2019 Barbaresco Rocaglie predictably made everyone’s top five of the trip. Thus far in its youth it shows glimmers of perfection from this mighty but very elegant vintage. Finally, Davide Carlone’s 2018 Boca “Adele,” represents the heights of quality for Nebbiolo in Alto Piemonte. It deserves a full-length article to describe its depth of complexity.

When Aussie native Tyler Kavanaugh isn’t surfing the famous waves of San Diego County in-between tasting appointments with our restaurant and retailer customers, he’s cooking and spending time with his wife and their new baby north of San Diego. He’s an Italian wine specialist, so all of you listen up! First on the list, and no surprise, is the 2019 Poderi Colla Barbaresco Roncaglie; again, near perfection. I knew the next wine would make his list because his eyes barely remained inside their sockets when tasting the the 2010 Andrea Picchioni Oltrepò Pavese “Riva Bianca.” We have the 2018 version of this arriving this month and it has the potential to match the extraordinary 2010. Tyler was a big fan some years ago after I tasted him on the wines when he was posted up as the buyer at the fabulous San Francisco Italian boutique wine shop, Biondivino, prior to onboarding with us. Enrico Togni’s “Martina” Rosato/Rosso (depending on what label you get!) tank sample also made my top 15. Simply too good to be labeled a Rosato, it’s as good as it gets for this Italian category—think an Italian version of López de Heredia’s Viña Tondonia Rosado in style, though much younger upon release! Andrea Monti Perini’s 2017 Bramaterra out of cask was superbly emotional and deserving of a top five list, as were the 2018 and 2019. So much life and energy in his wines! Finally, Tyler chose Katharina Wechslers’ 2020 Riesling Kabinett, which also made my top 15 and was ultimately positioned as my own official summer house wine of 2022. It comes entirely from the world-class cru, Kirchspiel., and it’s simply gorgeous Kabinett, with wiry acidity and the elegant beauty of its great limestone terroir.