Navelli, Abruzzo. Home to CantinArte’s high altitude white wines.

(Download complete pdf here)

Two months at a time was how I used to do the rounds with our growers. Winter and spring. Summer was too expensive and a fight for good lodging. Fall is too unpredictable with harvest to plan far in advance with most growers waiting for the right time, nerves on alert, hopes high but wearing a stoic face in case of disaster. That was all back before almost every year was hot and early.

I arrived home to Portugal in time for Thanksgiving week, obviously not a thing here. During fifteen days on the road I passed through the Loire Valley Cabernet Franc and Chenin Blanc country (skipping Sauvignon zones–no time this trip), Chablis, Champagne, and added more belly weight and a constant redness to my eyes in Piemonte, as the vines were strangely still green in most of the Langhe toward the end of November. Milan to Porto, an easy direct flight home, I thought, started in Monforte d’Alba at seven in the morning on a crisp, clear, Alp-majestic Sunday morning. Thirteen hours later I descended into a deluge in northern Portugal that started a month ago and hasn’t let up since. I thought I’d have half a Sunday to prepare myself for the coming catchup week, but airports and planes and the unusually extensive delays when you’re tired don’t make for great recovery.

Photo from Monforte d’Alba, November 2022

I can’t sleep on planes. Other than one time on the way to Chile it hasn’t happened again for more than ten minutes. I used to fly to Europe three times a year for a month each time when we first started our company. I figured that since I struggle with jet lag as much as I do that I may as well make it worth it by staying longer. Los Angeles (starting in Santa Barbara) to any EU destination is a real slog, a big disadvantage compared to East Coasters. Eventually I extended to two two-month trips in the last three years before I suggested to my wife and my business partner and co-owner and cofounder of The Source, Donny, that I move to Europe full time. Everyone was for it, surprisingly, and during a two-week vacation in Amalfi Coast’s perfect fishing village, Cetara, my wife opened the door with, “I could live here.” We landed on the first of September in 2018, a precise date our visa required of us, but after three months in Salerno, the major port town to the east of the Amalfi Coast, I knew Italy wasn’t our final European destination.

Now I prefer to travel in the summer, but this fall trip was a necessity because I’ve done so much scouting and bringing on new producers. I also need to keep up with everyone already on our roster. Last year, having packed a foam roller and nicely padded yoga mat (both necessities now to keep me loose while my body atrophies along the way), I took a six-week solo road trip from Portugal and on through northern Spain, southern France, northern Italy, into Austria, then boomeranging back to Germany, across into Champagne, then directly south through France, a right at Barcelona and back home by the first week of July. It was quite a loop and one of my most memorable trips to date. Despite higher costs, summers are the best time for my work on the road. Long days to grab as much visual candy as possible, nicer weather, light packing, and happier moods thanks to lighter summer fare, an all-you-can-soak-up supply of Vitamin D, and heightened spirits in hopes of a successful coming harvest. 2021 has a lot to offer. While difficult in some places, it put the “classic” back in many wines, despite the losses, though I guess losses are classic too.

2022 was the opposite of 2021. Brutally hot by European standards. However, the upside was that in many places the grape yield was very high, a good offset for what could’ve been a gargantuanly alcoholic vintage turned out not so extreme, though many producers, including Dave Fletcher, said he’d never seen such perfect fruit—no rot, no disease, clean and pretty. The balance of wines in each region is far from determined, but at least for the most part there’s wine to sell after the shortages of 2021. Vincent Bergeron, one of our new producers in Montlouis, explained that he had too much fruit and it was even more stressful as a short vintage because he wasn’t prepared to receive such an overload. 2021 was exactly the opposite. Everyone wants a “normal” harvest each year but we all know that the new normal is that everything is unpredictable. Feast or famine.

After two weeks with a party of four (one very light drinker that understandably didn’t pull her weight!), seven meals back-to-back with at least two bottles of Nebbiolo on each table (three the majority of the time), plus cantina visits before and after lunch, five different orders of Vitello Tonnato (top honors to Osteria La Libera, though La Torri and Bovio were a close second, all with different styles), seven orders of Plin in many forms (we couldn’t resist it during every meal, and top spot goes to La Libera again, though all were delicious), and six orders of Tajarin (top spot a tie between La Libera and Osteria Unione with only a slight textural difference in the pasta as the deciding factor), and without a doubt the best steak tartare at L’Eremo della Gasparina. It’s now Tuesday morning, and I’m still hurting a bit but craving a little Nebbiolo.

I’ve not written since last month’s newsletter and I’m happy to finally be stationary. As usual, there are so many things to talk and think about re: all that’s happened this year. It’s Thanksgiving week and I have a lot to be thankful for, though I don’t really get to that complete gratitude moment until the week between Christmas and New Year’s when I really feel like I’m left alone to focus on cooking and non-business talk with my wife. But like summer’s promise and the anticipation of the coming harvest and the mystery of opening nature’s unpredictable gift box for the growers, I can’t help but look toward 2023 and what’s coming our way with our new producers. In January, I will share with you a little teaser for what is on the horizon for the first half of the year. There are about fifteen new producers, almost all of whom have never been imported to the US before. You know, wine importers either continue to grow or they get poached to death, so I gotta shed this plin and tajarin weight (and the weight gained on the stop in France beforehand) and get back in the office to prepare for next year. There’s always a new fire-breathing dragon on our heels and promising new winegrowers to be found. I love this job, and though it’s a privileged and fortunate métier, it’s rarely a carefree party. Well, not until Saturday dinner.

California Events

Friday, December 9th, San Francisco retailer DECANT sf’s 4th Annual Winter Fête from 5pm – 9pm. Join shop owners Cara and Simi along with The Source’s Hadley Kemp for this Champagne and caviar pure drinking-and-eating event. Among many other fabulous bubbles, Hadley will pour some from us, including Charlot-Tanneux, Pascal Ponson and Thierry Richoux. Call for a seat at (415) 913-7256

Saturday, December 17th, Pico at The Los Alamos General Store Bubble Bash- Champagne & Sparkling Wine Tasting from 2pm – 5pm. The Source’s Santa Barbara representative, Leigh Readey, will be pouring at their outdoor tasting event in the Pico Garden and chef Cameron is splurging on caviar and oysters. $40 per person, tickets available for purchase at https://www. exploretock.com/picolosalamos/event/377637/bubble-bash

New Arrivals

The short list of arrivals not covered here in depth are the new releases from Wasenhaus and a reload on Artuke’s entry level ARTUKE Rioja and their insane value for such a serious Rioja, Pies Negros. Further along I go deep on two new producers, Champagne’s Pascal Mazet, and Abruzzo’s CantinArte. And included is an overview of Arnaud Lambert’s newest arrivals (too many good things there, so it’s a little lengthy), along with Dave Fletcher’s non-Nebbiolos.

New Producer

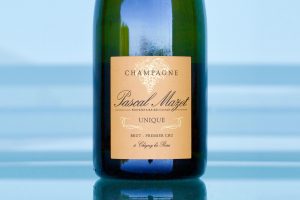

Pascal Mazet, Champagne

Thirty hours in Champagne is not enough time. I made stops exactly one week ago to Elise Dechannes in Les Riceys, and a new project in Les Riceys we’ll be starting with in the spring, Taisne-Riocour (a true linguistic challenge to pronounce properly in French), as well as Pascal Mazet in Montagne de Reims, before I jotted off to my hotel at Charles de Gaulle. I am as completely smitten with the Pascal Mazet wines as I was with Elise Dechannes’ the first time I tasted them, though the style is very different from Elise’s Pinot Noir-based Champagnes. Mazet's is the land where Pinot Meunier leads the pack.

The lovely and humble Catherine and constantly smiling Pascal Mazet established their domaine in 1981 with 2.5 hectares from her side of the family—enviable holdings in premier cru land on the Montagne de Reims communes Chigny-les-Roses and Ludes, and a grand cru parcel in Ambonnay. Even with such scant vineyard land, Pascal and his third son, Olivier, keep it interesting with six very different wines, soon to be only five. Most of the vineyards are gentle slopes facing southeast at 150m altitude with chalk bedrock alternating with calcareous sands and clay topsoil. They’re easy to spot: green jungle patches amid neighboring vineyards growing on desolate soil.

Little by little the Mazets improved their work. The purchase of a Willmes press in the 1990s gently increased the juice yield while reducing gross lees extraction at half the pressure of other presses. Organic conversion started in 2009 and was certified in 2012. Defining elements of their style are fermenting and aging in 225-liter barrels (of at least 15 years old) for eleven to fifteen months and their NV cuvées blended with wine from their 5000-liter “solera” foudre (continuously topped each year with new wine since 1981), followed by extensive lees aging in bottle—a minimum of six years, but often eight. The blends with the solera, Nature and Unique, are bottled only in particular vintages. If the wine needs dosage (to their taste), it is labeled as Unique, if no dosage, it’s Nature—each vintage is one cuvée only, and not the other; for example, 2013 and 2015 are Nature, 2014 is Unique. Dosage of all the wines is decided on taste and wine profile of the vintage.

“Scraping,” rather than tilling, is done with a very small tractor (lighter than one ton) to manage superficial grasses and weeds rather than deep gouging that can destroy deeply embedded flora and fauna habitats. While not interested in fully pursuing biodynamic practice, some similar concepts and treatments are employed, like plant infusions for vineyard treatments made from nettle, horsetail, yarrow, dandelion and consoude (known as Symphytum in English), a flower with a multitude of medical uses for animals (including humans!) as well as plants.

Pascal (left) and Olivier Mazet

At age of twenty-seven, Olivier Mazet took full control in 2018 after completing his university studies in 2014 with an engineering degree specialized in viticulture and enology from the Ecole Supérieur d’Agriculture, in Angers. Olivier’s long view is focused on agroforestry to improve biodiversity in and around the vineyards to help their resilience against disease, improve soil structures by letting nature do a lot of the work—with its billions of years of experience and knowledge—and to try to better cover their viticultural carbon footprint. Olivier’s older brother, Baptiste, also joined the team in 2020.

The vineyard collection is about 1.3 hectares (3.2 acres) of Pinot Meunier, 46 ares (0.46 hectare) of Chardonnay, and 23 ares of Pinot Noir, all with an average age of forty years (2022), and 22 of sixty-year-old Pinot Blanc. The yield from their 8000-10000 vines per hectare (similar to Burgundy) in a normal year is around 55hl/ha.

Mazet’s solera foudre is a singular experience. I asked Olivier for a taste of it during our first visit together. He looked to Pascal, who seemed surprised by the request, but he agreed to fill a small bottle to taste. When out of the room, Olivier raised his eyebrows, smiled, and said “It’s very unusual that he lets anyone taste from the foudre.” Over the years I’ve often thrown out the descriptor for extremely minerally wines that, “they taste like liquid rock!” This wine was a recalibration of that description in that I would say it was equally rock and metal.

It truly was like tasting liquid rock and metal, almost no fruit at all—purely elemental. Never in my entire career have I had a wine so specific as that.

What surprised me the most was how unoxidized it was and the purity of color, like looking through the prism of a diamond, the flickering reflection of the sun off the glistening sea. Its taste I will never forget and will always recognize in the mix of Nature, Unique and Originel, the wines to get dosed with this vinous nitrous oxide.

The foudre

“Nature” comes from all of their parcels and is a blend of 45% Pinot Meunier, 30% Chardonnay and 25% Pinot Noir. 60% is 2013 vintage wine while the remainder is from their single 50hl “solera” foudre, with zero dosage. “Unique” mirrors “Nature,” though it comes from an entirely different vintage base wine, as mentioned earlier. The grape mix is the same, as is the amount of vintage wine, this case from 2014, while the remainder is from their single 50hl “solera” foudre, with 4g/L dosage. “Originel” is composed of 35% Chardonnay, 35% Pinot Blanc, and 15% each of Pinot Noir and Pinot Meunier, all from two different plots: Chardonnay from “Les Sentiers” on chalk and clay, and Pinot Blanc from chalk and sand (with correspondingly earlier ripening) of “La Pruches d’en Haut,” an originel plot that was listed as a terroir of Champagne before the 1800s. 60% of this wine is from 2013 and 40% from the “solera” foudre, with 3g/L dosage. “Millésime,” as the name suggests, is Mazet’s vintage Champagne. The 2015 is a blend of all the different parcels with a mix of 45% Pinot Meunier, 30% Chardonnay and 25% Pinot Noir. It’s aged exclusively in 225-liter French oak casks of at least 15 years old, with zero dosage.

CantinArte, Abruzzo

I will be the first to admit I am not an expert in Italian wines, despite working in and visiting Italian producers regularly since 2004 and a one-year residence in Campania; it’s a country hard to master if it’s not your main focus. I improve every year but the depth of this peninsula and its islands and mountains can be overwhelming. Abruzzo, for one, is a region I haven’t even tried to wrap my head around (though I don’t have the time yet to dig in like I’d like to) because of its vast expanse and my lack of I’ve been to Abruzzo twice, and other Italian wine regions like Piemonte thirty, if not forty times. I have a grip but still feel like an advanced amateur in Piemonte, so you can imagine how I feel about Abruzzo. I can talk about a few of the big names in Abruzzo and their unique styles (and complain about their strangely high prices), but I can’t speak about the appellation as a whole—maybe only on a flashcard level. For this reason I’m glad that our new Abruzzo producer CantinArte (which I competitively tasted among other wines in the region to figure out if they truly were a stylistic match for us in taste and philosophy, before opting in) has their own small section of Montepulciano grapes in Bucchianico, in the Province of Chieti. It’s about ten kilometers from the Adriatic on a soft sloping southeast exposition (a preferential direction for freshness!) on deep clay topsoil, which is helpful to mitigate arid weather through good water retention. Plus, it’s in the middle of nowhere high up in the mountains with mainland Italy’s most consistently clean air (a unique fact), with no one else nearby.

While Francesca Di Nosio’s husband Diego Gasbarri developed his career as an engineer with a degree in Environmental Engineering (an expertise quite useful for their organic vineyards and olive tree groves) and built his small company from scratch in Civil engineering, she was bitten by the wine bug in her teenage years. Her first inspiration was her grandparents, who made wine only for the family’s consumption. Her studies in university were initially focused on Latin and Ancient Greek, and later Marketing and Communication, but a trip in her teenage years to UC Davis in 1988 with her father sparked an interest in winegrowing that eventually grew into a spiritual and cultural bonfire. Eventually she went to France to work in vineyards around Lyon and then a year at the biodynamic Chianti Classico cantina, Querciabella. During her time in Greve in Chianti, she became convinced of her future in wine and went home to start CantinArte with the Montepulciano vineyards her grandparents planted in the 1970s.

Francesca Di Nosio, CantinArte

Curious about all things, Francesca loves most her connection with people, the talks about culture and wine and food. A mother of two, she remains a complete romantic overflowing with hospitality and kindness and gushing with an eagerness to please. (Anyone would laugh if they heard some of the enthusiastic and fun voice messages I’ve received from her over the last two years.) When asked what she would like for people to feel about her wines, the take away after mentions of mineral freshness and uniqueness was that she wants people to feel their joy. What else?

CantinArte’s 740m white wine vineyards

The vineyard project high up in the mountains where they’ve planted Pecorino and Pinot Grigio are in Diego’s familial neighborhood, Navelli, a gorgeous old rock village in the Provincia dell’Aquila, an hour drive up into the mountains from the Adriatic to a completely different setting from their Montepulciano vineyards. These new vineyards (first vintages bottled 2021 for both varieties) are at an unusually high altitude for Abruzzo viticulture at 740m (~2,400ft). At first, they thought maybe it was a gamble to go so high, but the results are beyond promising. This place is perfectly suited for these white varieties with a bedrock and topsoil that have an uncanny resemblance to those of the Côte d’Or (a place I’ve dug around in for years): fractured, stark white limestone rocks from a different geological age mixed with reddish-brown clay atop limestone bedrock. They are some of the most striking examples of both varieties I’ve had, and not surprisingly unique with their tense, mountain acidity and even some petillance in the 2021 Pinot Grigio IGT Terre Aquilane “Colori” that gives it extra charge. I remain perplexed by this Pinot Grigio (not only for its bubbles) with its vinous capture of clean mountain air, sweet green herbs, sweet lime and green melon fruit. I’m constantly surprised when I think about this wine (often) and what they did differently than others, outside of spontaneous ferments, low total SO2 (less than 60ppm), and organic farming at super high altitude. I know, Ted Vance, the perpetual wine sales guy, now waxing lyrically about Pinot Grigio? Don’t write it off so easily. This stuff is different, and I guess one shouldn’t summarily dismiss any grapes from the Pinot family when they are done in a serious way!

Though the Pinot Grigio is captivating, most will likely go for the 2021 Pecorino IGT Terre Aquilane “Colori,” not only because it is a more classical variety from these parts, but also because it is likely viewed as more complex. High altitude Pecorino works, and the biotypes Diego selected for the plantation originate from northern Abruzzo at very high altitudes— mostly in territories without much commercial production but rather from families who produce for themselves. Here, the brine of the sea in the wine is exchanged for a cold mountain, herb-filled aromatic breeze. This variety seems to have a natural salinity anyway, so you won’t miss much there. The difference between here and 400m down and closer to the sea is that the mountain wines will have a little less oxidation, higher pH levels (3.10-3.15 for both Pinot Grigio and Pecorino), more angles than curves, pungent rocky mineral impressions due to the rockier soil with little topsoil, and the effects of a massive diurnal shift at the high altitude—summer days around 35C (95°F) drop to 16°C (60°F) at night—and without the big spice rack imposed by more heat and solar power closer to the sea at lower altitudes. This white wine project seems to be Diego’s thing more than Francesca’s—it’s his home turf while closer to the sea is hers—and his new Pecorino experiment out of amphora I tasted a little over a month ago caught me with my jaw on the floor, yet again. I can’t wait to see if that one gets into bottle in the same shape it is in amphora!

Diego Gasbarri, CantinArte

CantinArte’s two parcels of Montepulciano in Bucchianico sit around 300m (~1000ft) and were planted in the mid-seventies, with another part in the early 2010s by Francesca and Diego. The younger vines are used for the Cerasuolo d’Abruzzo and the Montepulciano d’Abruzzo “Ode” and the older vines for their Montepulciano d’Abruzzo Rosso Puro.

I admit that my greater initial personal interest in Abruzzo was to find a mesmerizing Cerasuolo rather than an Abruzzo red or white. I’ve had a few Cerasuolo from names that most in the trade know well but can rarely find—let alone afford—that give me a stir while others can be a lot of fun to drink, but most are innocuous wines. I find that the most compelling reds and whites of Abruzzo are so often crafted in such an individual way at very specific cantinas under the direction of uniquely special people that it was hard to imagine finding another inspiring standalone superstar in a sea of Trebbiano and Montepulciano. My interactions with CantinArte’s Cerasuolos, like the 2020 Cerasuolo d’Abruzzo, and the 2019 before it, hit the mark. I also found that in classical style for this category with high quality producers that they are quiet and tucked in upon opening (the best often need decanting to get past too much gas, and, well, we don’t have all day when we’re ready to drink rosé, right?) which is further exacerbated by a cold serving temperature straight out of the fridge. But with some time open, the structure of this twenty-four-hour skin maceration concedes its authority in CantinArte’s Cerasuolo to fresh red spring fruits and the joy Francesca wants us to experience. It’s a wonderful wine when it hits its stride (half an hour after opening) and maintains a very focused direction. A perfect Sunday lunch wine served at a red wine temperature, it will bloom with the promise of spring into a leafless autumn afternoon meal with good company. Today being Thanksgiving (at least as I write this segment on a dreary, rain-filled Portuguese morning), my mind screams, “Everyone knows that Beaujolais is a fabulous match for today’s traditional fare, but bring on the Cerasuolo!” It’s made in a straightforward way in steel tanks and with grapes organically farmed close to the sea at 300m on clay, facing southeast.

The 2019 was a very good but the 2020 Montepulciano d’Abruzzo “Ode” may even be better. My first interaction with these fully destemmed reds on day one was very good but the second day was always another level for both—first day expected, the second a good surprise for a variety that often seems to put all the cards on the table in short order. Its freshness afterburner (even more so than the first day) demonstrates how picking is prioritized on the earlier side in the season along with rigorous sorting. For these reasons, they show little to no sense of desiccation or brown notes in the spectrum of fruit (a concern for me with young wines from these sunny parts), just a minerally, cool and refreshing palate texture, and ethereal aromatic qualities on top of its natural savory earthiness. Ode is more of a straightforward approach with stainless steel fermenting (10-12 days) and aging (12 months) and is void of tweaks that make it feel heavy-handed, using unique techniques rather than relying on excellent and conscious organic farming with an environmental engineer’s eye for detail. And of course, the joy of the family behind it.

The 2010 Montepulciano d’Abruzzo “Rosso Puro” comes from the vineyard of Francesca’s grandparents planted in the 1970s. Since the beginning, even prior to the organic certification in 2014, only copper and sulfur were sprayed in the vines when she first started. Francesca says that the main difference in the vineyard is the evolution of the yeasts from the vineyards without any synthetic treatments. As mentioned, this wine is grown on clay on a southeast face, and was destemmed during its three-week fermentation/maceration and raised for three years in no new oak, instead with some first year and mostly older used French oak barrels. This southeast face is key for the freshness of both reds and their Cerasuolo. Though Rosso Puro is one year short of being a teenager, it’s in its middle age, its prime, and perfect now. It’s a good introduction to southern-Italian wine style—even though it’s from the center of Italy—with reminiscent notes similar to aged Aglianico in Taurasi, minus the thick-boned structure. There is very little of this wine available and we expect the 2013 to arrive with our next order.

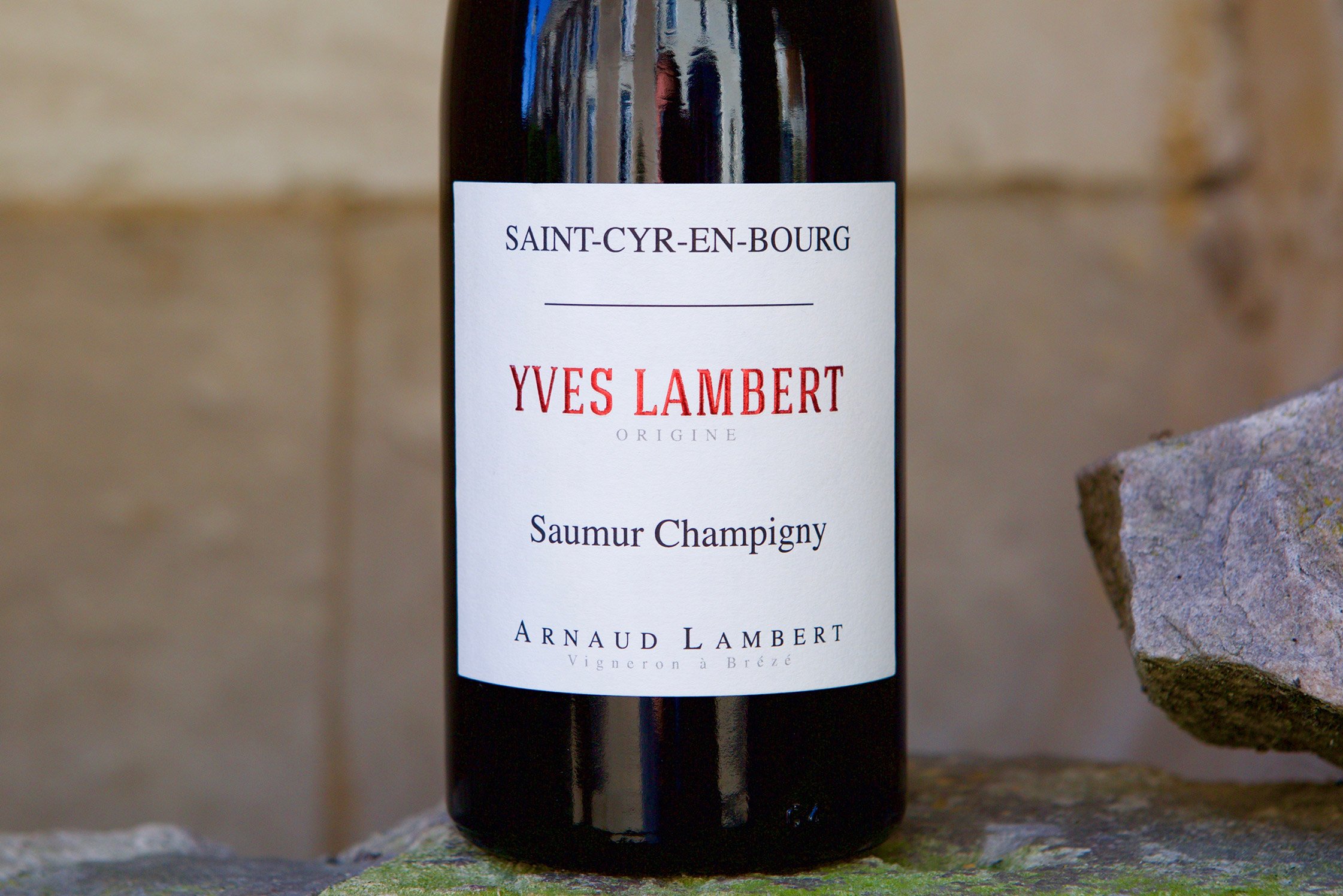

Arnaud Lambert, Loire Valley

There are few who candidly share their process with me as much as Arnaud Lambert does, and I had yet another great visit with him a few weeks ago. Perpetually on the move, he always has something new to share about his progress. We had lunch in Saumur at Bistro de la Place in the center of town. It was cold and drizzly. Perfect for a lunch of foie gras and trotters—my usual “light” fare in France; it really is hard for me to stick with “clean” eating in that country. Arnaud asked me to pick the wine and I was pleasantly surprised to see a bottle of 2018 Domaine de la Vallée Moray’s Montlouis “Aubépin,” a wine and producer unfamiliar to Arnaud, furthermore quite unfamiliar in the world as of now, though that won’t last. The sommelier perked up when I named the wine. He came back and poured. I said nothing, just waited. Arnaud took his time, eyes in contemplation, swirling the glass, then sloshing the wine around in his mouth. It was a very impressive first glass (which means the second will be even better!) and I knew he was taken long before he said anything. He commented how remarkable it was for 2018, a difficult vintage with depth and stuffing, which this wine has in spades. During my previous visit with Arnaud, Romain Guiberteau and Brendan Stater-West, I talked about the new producers I’m starting to work with in Montlouis, including Vallée Moray. I was happy to share this bottle. Hopefully Arnaud will come with me to Montlouis on my next trip to meet Hervé Grenier, the humble master who crafted this gorgeously deep Chenin Blanc, among other unexpectedly fabulous and authentic vinous creations. Hervé’s wines will be on offer in January, though the quantities are painfully small.

Chenin Blanc

Everyone’s lucky to have access to this bigtime lineup from Arnaud. It’s serious juice from recent vintages that he feels have moved well into the direction he’s pursued since his start, tweaking and experimenting along the way to find this specific line. Oak decisions on Chenin Blanc are milder than the recent years—a conversation we’ve had regularly. The previous years were good, and often great, but sometimes time is needed to punch through the oak when the wines are young. Eventually they make it through but perhaps at a cost of some delicate nuances. One thing I’ve noticed with the Saumur wines we work with is that there is often a lot of intensity and vibration rather than rhythmic melody. Arnaud has doggedly sought and seemingly found his tune, a taming of the shivering intensity of this area of Saumur, highlighting the vinous quality often left behind or beat down by the wood in its youth. The innocence of Midi always stood as the north star to his range of Chenin for me, with its crystalline purity, captured joy, and echoes of Arnaud’s deeply hued and thoughtful Belgian bluestone eyes.

There are a few goodies arriving from Arnaud’s entry-level Chenin spectrum. 2021 Clos de Midi is more than just a good opener for the range. This year is second to none compared to every young wine I’ve had from this vineyard in the middle (midi) of the slope. I asked Arnaud for more entry-level white, and while it’s almost impossible to increase the quantity of Clos de Midi, he proposed his 2021 St. Cyr en Bourg Chenin Blanc. This all comes from his organic parcels in St. Cyr en Bourg (home to Coulee de St. Cyr and Les Perrieres, just across the way from Brézé), and is made the same as Clos de Midi, in stainless steel. You can’t go wrong with any of Arnaud’s 2021s.

The triumphant trio of Chenin Blanc starts at the blocks with 2020 Clos David, a straight shooter and in all ways minerally and rocky, followed by the powerful and usually slow to evolve (though this year is a little more extroverted than years past) 2019 Brézé grown in deeper clay soils atop tuffeau bedrock, all anchored by the 2019 Clos de la Rue. Each is worthy of any serious wine program, though the Brézé is extremely limited. 2019 is likely the best bottling of this wine I’ve had (when young), but Clos de la Rue remains king for me year in and year out after tasting these wines since the 2009 vintage—the Brézé cuvée first bottling was 2014. Seemingly without limits in evolution and a constant rediscovery from one glass to the next, Clos de la Rue is poised with balance and deep core strength. Though Clos David is the bargain cru at the price, and Brézé the muscular unicorn with only two barrels made, Clos de la Rue is the must-have in the lineup.

Cabernet Franc

Arnaud is in perpetual internal war over his reds. I’ve often pushed for Clos Mazurique to be the guiding light: matter over mind, and hand. Over the years Arnaud reduced his extractions, starting in 2012 with fewer than one movement each day down from three during fermentation—a good decision and still upheld though with even fewer now, only around three vigorous movements for the entire length of fermentation and extended maceration. Next was zero sulfiting until after malolactic fermentation, which turned out to be far less risky than expected. (All one must do is go into his freezing barrel room to know that almost nothing will grow in those wines, only the most resilient of cellar molds on the outside of barrels and the tuffeau rock walls and ceiling.) Eventually that evolved into a solitary addition only at bottling with not a milligram before. The total sulfite levels today are around 25ppm (25mg/L). Both steps were crucial in his evolution. Most recently, however, is the approach on new wood with less is more. This step is more recent, but if there were ever a vintage to digest the new oak entirely, it would be 2019. It also helps that the top red wines, Clos Moleton and Clos de l’Etoile, with about 30% new oak, were in those same barrels for thirty months to eventually shed most of the undesired wood nuances and wood tannins. Considering the pH levels of these wines, they will never flaunt the wood as other higher pH varieties. I don’t really know why that is, but I’ve observed it, as have many other winegrowers.

Newer wood tames, manicures, and sculpts. All good things with Bordeaux and Burgundy, I guess, but not for me with Cabernet Franc from the Loire Valley. In some ways, newer wood forces manners and etiquette, though I find the nature of Cabernet Franc to be earth-led, with sunlight, spring flowers and spring fruits, a little bit of untamed beast, and maybe even a little solemnity. It’s not at all a confectionary variety with a party personality, so I don’t find that it melds well with sweet, vanilla, toasty, resiny, smoky new wood on it. New wood often neuters Cabernet Franc’s most alluring attributes (as it does other wines), trading out the wild forest, underbrush, and wild animal for stately statue gardens and their regularly trimmed shrubbery. The style works anyway with Cabernet Franc caught somewhere between Burgundy, Bordeaux and the overly polished and utterly boring (again, neutered!) versions of new-wood Côte-Rôtie and Hermitage. Indeed, Saumur rouge and Saumur-Champigny are not the Northern Rhône Valley’s rustic, burly, salty, meaty, bloody, metal, minerally type—though that is what I often want it to lean more toward, though only toward, without succumbing entirely. I think most of us have a good idea of what would happen if one goes full Tarzan with Cabernet Franc. And this variety isn’t Red Burgundy: celebrated, predictable, still exciting (sometimes when young, but mostly with older wines from cooler years), but rarely unexpected, even when the very best show their might, excluding producers like Mugnier, and Leroy (may she live forever, though I can no longer afford or justify the cost to drink anything adorned with her name and crown.) Can these overly crafted wines be a little too good? Like Tom Brady-too-good? So much so that you don’t want it anymore? That you should root for someone else? An underdog such as a Cabernet Franc?

I find that Saumur and Saumur-Champigny are often a reflection of its residents, their good manners, happiness and generosity, their contained, clean and well-dressed but slightly casual presentation and warmth; it’s only the weather that brings the chill here, not usually the people. I almost moved to Saumur. I love the place; its gorgeous tuffeau off-white castles and even its simplest tuffeau structures and barns. It’s easy to navigate in the city, much of which was rebuilt after World War II, though not as badly damaged as other Loire Valley cities like Tours. I always feel safe in greater Anjou and Touraine. I don’t mean only from a physical safety perspective but rather that I never feel rushed, like I’m not going to get run over, harassed, or impatiently talked to when my French isn’t on point. Maybe the soft rolling hills and the serenity of the river soften them. Maybe it’s that they lost too many people and things during WWII, which forced a lot of familial and city reconstruction that made them humbler than some other French wine regions?

I feel Arnaud continues to move closer to embracing the earthen, well-dressed beast Cabernet Franc can be, despite his reference points and training in Beaune and seeming desire to be closer to a Burgundy wine in overall effect. It’s not a bad objective to want to walk beside Burgundy, though I’m still confused even when I use the term “Burgundian” to try to bring understanding to the style of a non-Burgundy wine. I think I used to know better what I meant by it.

Cabernet Franc from Saumur and Saumur-Champigny somehow expresses its dark clay and rocky limestone topsoil and tuffeau bedrock. In the best examples it seems like they drop the clusters on the vineyard ground, toss in some aromatic brush and herbs, wild berries, mash it up a little and then throw them into fermentation bins with the grapes, thereby collecting all that earthy and wilderness nuance. That’s where I see Arnaud going in overall profile, and I do hope that’s where he ends up. Cabernet Franc is an easy grape in many ways when good table wine is what’s wanted, but despite its agreeability its inspiring renditions only come from top sites grown by top minds and hard workers. Farming is crucial and the wines need to be left alone in the cellar to sort themselves out and be put to bottle without much of a mark of ego, neglect, bad taste, or indecision. Intention with Cabernet Franc is crucial. Epic never happens here by accident.

Leading off the red range are Arnaud’s two impossible not to like wines (if you have taste for Loire Valley Cabernet Franc!): the 2021 Saumur-Champigny Les Terres Rouges and 2021 Saumur Clos Mazurique.

Here you will find Arnaud’s best red wines that have ever borne these labels, no doubt about it. I said it while tasting with Arnaud a few weeks ago, and he agreed.

He explained that he found a new way! (As he always does every single year.) They are gorgeous and follow a line of truth for this variety expressing the purity of their terroirs through simple, more-thought-and-less-action winemaking, all a concession to the organic farming (started in 2010) and the need to work with the vine’s nature instead of against it. I shouldn’t spend so much time on them because despite a good number of cases of each arriving, all of them already have a devout following in our supply chain and they’re all expecting their usual share. Perhaps these two reds, like Clos de Midi, are now out of most by-the-glass ranges, but for the price sensitive section of the wine list’s bottle selection, they will be stars for those who are still concerned about the tally on the bill in the face of an increasingly more expensive world.

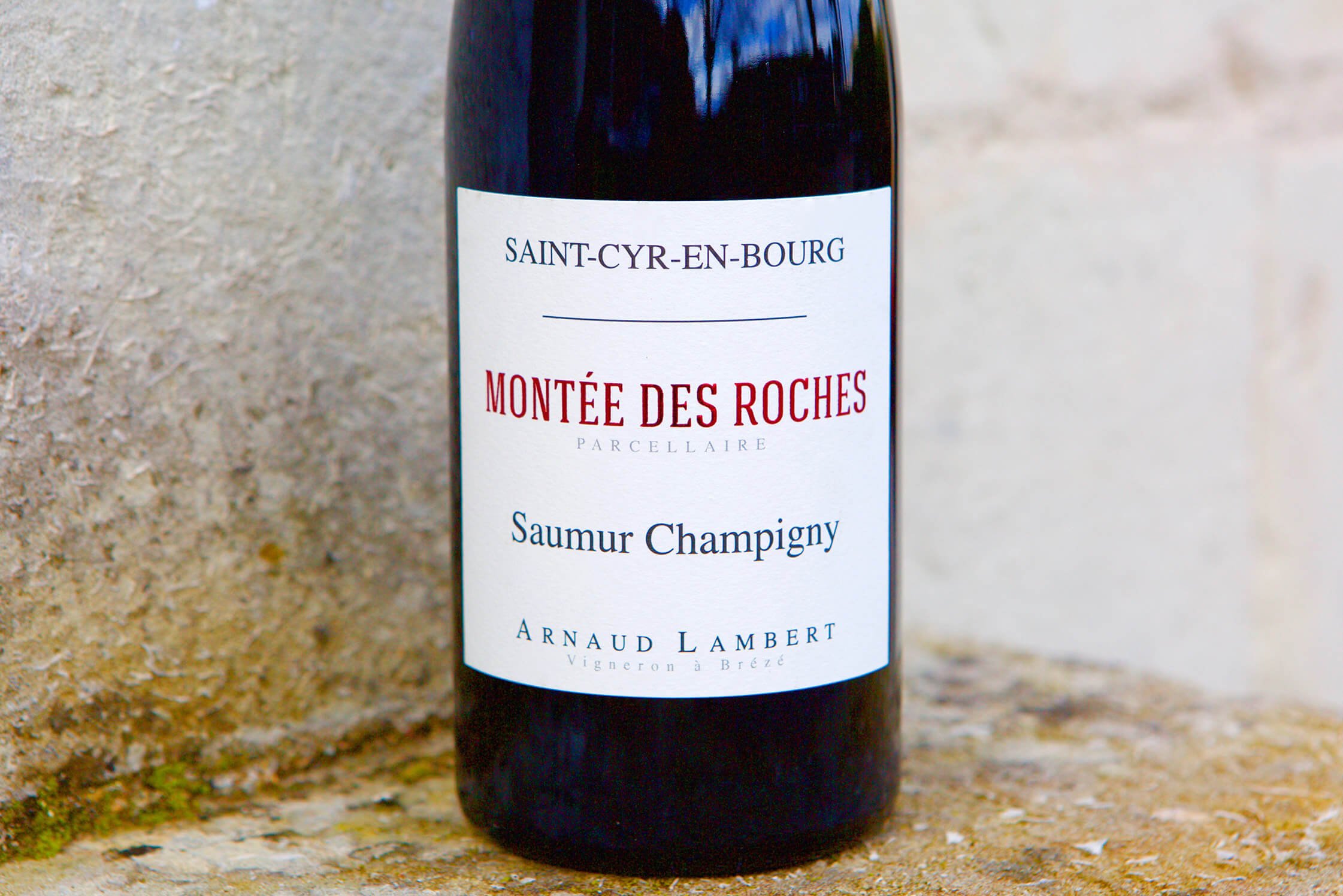

Comparing the hills of Brézé and Saint-Cyr through the lens of Arnaud’s wines is a testament to the validity of terroir. The hills more or less look the same in shape, though Brézé is far more attractive with its forest cap and the famous Chateau de Brézé’s ancient tuffeau limestone walls encircling it like a crown, compared to Saint-Cyr’s slope capped off with the industrial Saumur winery co-op on top, which Arnaud’s grandfather helped establish. The big difference between them is that Saint-Cyr could be described as more homogenous in soil structure with a lot of clay topsoil on most vineyards, while Brézé is a patchwork of many different topsoil structures ranging from almost pure calcareous sand (Clos David), sandy loam (Clos Mazurique, Clos Tue Loup, top section of Clos de l’Etoile), clayey loam (Clos de la Rue), and clay (Brézé cuvée, and bottom section of Clos de l’Etoile). Both hills have tuffeau bedrock and most of the Cabernet Franc parcels have deeper clay topsoil atop the roche-mère. Think of clay-rich sites as a George Foreman-like wine, clay-loam as Muhammad Ali, and sand as Oscar de la Hoya.

The pity of this lineup of reds is the missing comparative between Brézé’s Clos du Tue Loup and Saint-Cyr’s Montée des Roches (gravelly loam), the latter of which is not on this boat. Arnaud’s 2020 Saumur “Clos Tue Loup” was raised in only older barrels for a little over a year. I’ve always loved this wine for its higher tones, deep red fruit and cool mineral palate. It embodies what I love the most from this hill and the balance of power. The big hitters, 2019 Saumur-Champigny “Clos Moleton” (Saint-Cyr) and 2019 Saumur “Clos de l’Etoile” (Brézé) are clear demonstrations of somewhat subtle terroir differences that make quite an impact on the final wines. Same bedrock but different topsoil. As mentioned, Clos de l’Etoile has two different soil structures. The upper section is sandy loam and the lower section, clay. This combo makes a wine with great structure but also a little more lift than its near twin on the other hill. By contrast, Clos Moleton is atop a big slab of clay. Like Foreman, it’s formidable, methodical, powerful, intense, with a little chub and a fun personality, especially with more age. L’Etoile is a heavyweight, no doubt, but much faster hand and foot speed and equipped with a silver tongue: Ali. 2019 is one of Arnaud’s greatest achievements in red which makes the miniscule quantities of these two powerhouse reds unfortunate. When you pull the cork do it for a table of two (for sommeliers) or at home with a good friend and a nice long conversation, rather than at a party. Evolution is key here and these heavyweights need twelve rounds in the glass to put on the full show.

Fletcher, Barbaresco

(Non-Barbaresco wines)

Holding up the rear of this newsletter (the caboose, if you will) is the Aussie expat living in what was once the Barbaresco train station, Dave Fletcher. The difference between Dave and many other foreigners making wine in Langhe is that he works a tiny, one- man operation with a little help only when he really needs it, unlike the millionaires buying all vineyards that are on the market for double the previous year’s going rate. His day job since 2009 has been at Ceretto, working as a cellar hand where he eventually became their full time winemaker, pushing organic and then biodynamic farming on them, with great success as they are now under both cultures. I finally visited Ceretto on this last trip in mid-November and I cannot believe the style change he helped instill. The wines now are crystalline, bright, aromatic, almost no new wood (around 50% new when he started but now less than 10%), and graceful, like Vietti’s new style. Dave’s renditions of Barbaresco under the Fletcher label are the real deal. They’re not from big botte because he doesn’t have the volume from any Barbaresco cru to fill one because there are only about fifty or so cases of each made. He’s a real garagiste, or I guess I could say stationiste because he lives in and ages his Barbarescos (in the underground cellar) in the train station he and his wife, Elenora, bought and renovated. I love being in that building, where they did their best to preserve the layout on the first floor, ticket window and all. It’s easy to imagine it filled with Italians traveling away from their home in these hills to Turin for work, after having abandoned their multi-generational vineyards to enter manufacturing jobs just to survive. It was a sad time then and the Langhe was the poorest area in all of Italy after WWII. Things have changed. Despite its current overflow of riches, the vast majority of the Piemontese still carry on many generations of humility, warmth and comradery. It remains for me my spiritual Italian homeland.

Dave has pushed his Chardonnay on me for years. They were always good and often I didn’t let him know it because even though I liked them I thought our customer base would think, “Aussie Langhe Chardonnay? Wtf, Ted?”, when Aussie Barbaresco was a tough sell to begin with. I was convinced that Chardonnay might turn the Piemontese traditionalist buyers off from his Nebbiolo wines. I’ve come to realize that that was just me standing in the way, with good intentions of course, to protect and help build Dave’s traditional Piemontese style wines in the market first before letting in his irrepressible Down Under. Dave’s 2021 Chardonnay C21 exemplifies what he’s capable of and his New World versatility and open mind. He’s proud of this wine, and he should be. He loves Burgundy, and he’s followed its stylistic line with his vineyard planted on extremely high pH limestone soils (though here its sandy topsoil compared to Burgundy’s clay), his early picks to preserve tension (this vintage August 21, but he says this is the new norm) and prefers grapes without much direct sun contact—more green than golden. It’s Burgundian in style in that its 30% new oak and the rest in older oak casks. If one were to serve it blind—things we only do with non-Burgundy Chardonnays to try to fool each other into thinking its a Burgundy—especially after it was open for thirty minutes with a little bit of aeration in the glass before my first sniff and taste, I may have a hard time going away from Burgundy, though probably not within the Côte de Beaune. It’s not really New Worldy (mostly because of the similar calcium carbonate influence as Burgundy) but rather somewhere between the style of PYCM–though a little tighter and not fluffed up–and JC Ramonet, but less toasty and lactic. Perhaps its softer textural grip would give it away and take you right back to the Langhe, but I doubt it, unless you know well Langhe Chardonnay. It’s a good wine indeed, especially at its fair price for this category and quality. Definitely worth a look for those craving that fairy dust that’s so hard to find outside of Burgundy’s Chardonnay wines.

Orange wine is in, and Dave’s 2021 Arcato is a dandy. He prides himself on craft and he’s sharp on technical tastings, so you kind of know what you’re getting here when you mix early picked 75% Arneis destemmed and crushed, and 25% Moscato whole cluster fermented and macerated, and a final alcohol of 11.8%, labeled 12. It’s a very technically sound wine from a classical point of view, but it’s also delicious and intriguing, a joy to drink. I like it a lot. Not so quirky, just well done and with a lot of personality from these two grapes, one on the neutral and understated side and the other more flamboyant and abundantly aromatic as a still wine. He also nailed the label for this fun wine category—a retailer’s dream etichetta for this category.

I’ve been a fan since my first taste of Dave’s Barbera d’Alba made with partial whole clusters. His new rendition, the 2021 Barbera d’Alba comes from a vineyard in Alba with sixty-year- old vines. He said he had to do a lot of sorting because of Barbera’s soft skins, which tend to shrivel a little more than other regional red grapes. The 2021 shows a little bit more mature development on the red fruit due to the heat spike, and he intends to do two picks in the future because of the variability of maturity on the vines. This is delicious stuff and a fun reboot for this ubiquitous Piemontese grape with southern Italian origins.