Forteresse de Berrye

This website contains no AI-generated text or images.

All writing and photography are original works by Ted Vance.

Short Summary

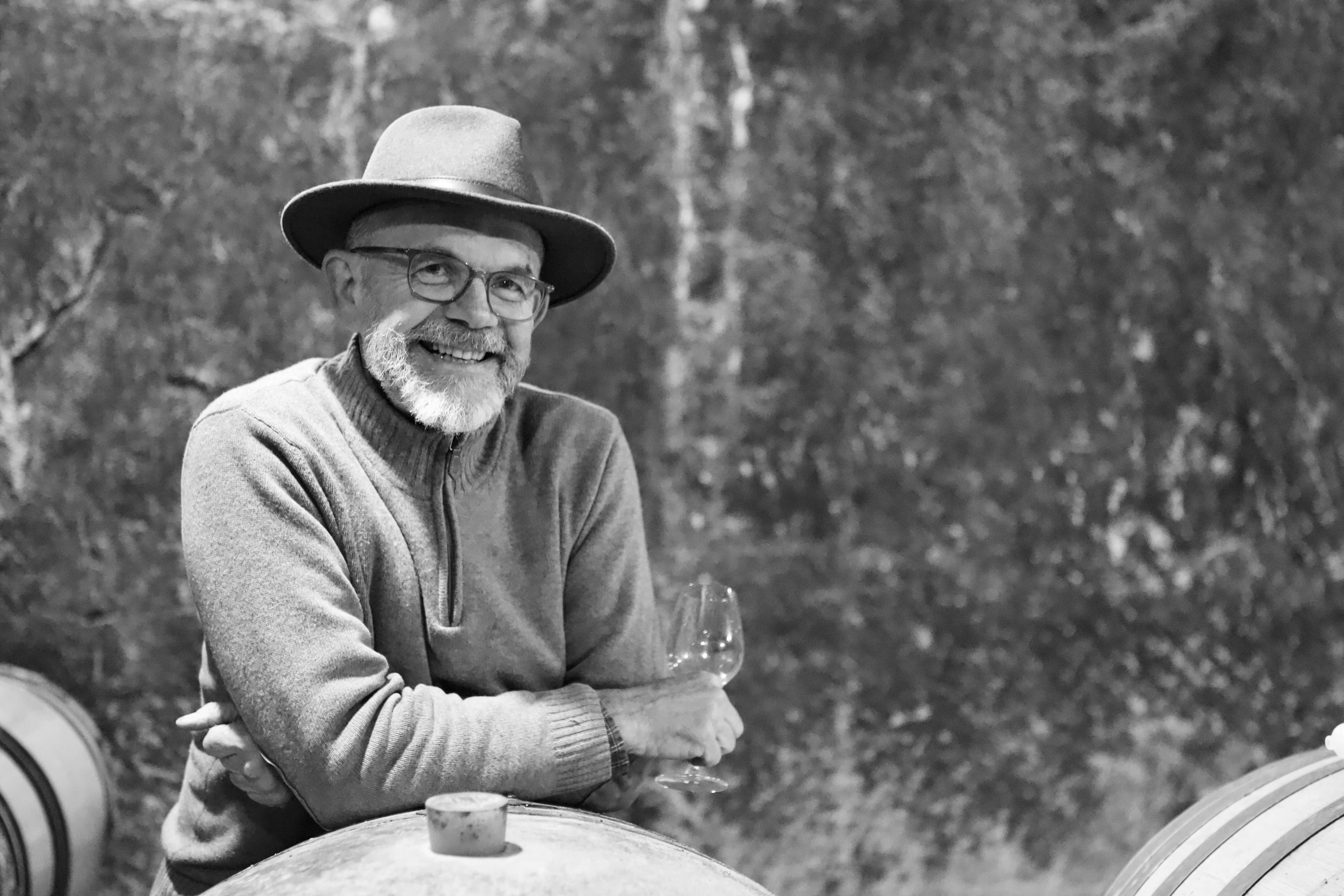

Forteresse de Berrye’s expressive and terroir-focused wines are crafted in a simple and direct way by its new owner, Gilles Colinet, an agronomist and agricultural engineer—among the many métiers of his diverse professional life. Starting with the elimination of all chemical applications in 2019, he began organic culture in 2021 (cert. 2024). His winery is a former military base, the fortress and vineyards strategically located on one of the higher hills in Saumur (~100m). The vineyards grow on predominantly yellowish tuffeau limestone with relatively thin topsoil (a mixture of silt, sand and clay, depending on the parcel), and the average age of the vines is 30 years. The 26ha property is planted to 10.5ha of vines while the rest is wild forest and 6ha of newly planted trees to further encourage biodiversity. Winemaking practices and bottlings continue to evolve, and most will be fermented and aged in concrete and/or predominantly old oak barrels.Full Length Story

Forteresse de Berrye’s expressive and terroir-focused wines are crafted in a simple and direct way. Its new owners, Gilles, an agronomist and agricultural engineer (among the many métiers of his diverse professional life), and his wife, Sandra, have eliminated the use of all chemical applications in 2019 and began organic culture in 2021; they expect certification by 2024. They began to replace the missing pieds (vine stocks) with high-quality oriented biotypes and planted six hectares of trees on the 26-hectare property (12.5ha of vines) to improve the overall biodiversity of the landscape in support of the forest-capped hill. For them, agroforestry is crucial for repairing the land, though luckily for them (and us), the property’s many parcels were well-tended and not destroyed by excessive use of synthetic products prior to their arrival. Gilles says that the land was in quite good shape overall due to the few annual treatments in this low precipitation and low humidity area of Saumur, perhaps one of the driest areas of the Loire Valley overall due to the rain shadow of the Armorican Massif to the west. Many of the old Chenin Blanc bottles left behind in the deeply quarried tuffeau limestone caves by its former owner drink well, with only the quality of the cork being the determining factor.

Our first introduction to the area of Berrie (though the domaine name is spelled Berrye) came by way of none other than one of our Saumur heroes and most inspiring success stories, Arnaud Lambert, an unknown just a dozen years ago who’s now seemingly world famous. Always interested to know if there was another area of Saumur with potential like Brézé before its inevitable rise to global fame, Arnaud responded to our inquiry by saying that Berrie could be the equal of Brézé, if not even better. This nugget was on the back burner until we received an unexpected email from Gilles’ daughter, Céléste, a young Parisian braving life in New York City. In her message and a subsequent phone call she told us about how her family had taken over and their conversion to organic farming.

In the spring of 2022 during breakfast at Arnaud’s, I admitted (as though I’d been keeping a secret from him—winegrowers can be a little territorial sometimes, even when they are good friends as he and I are) that I was off to visit the Forteresse de Berrye (FdB). Arnaud, a Saumur team player, was interested to know more and said that at one point he wanted to buy the property but wasn’t up to undertaking the restoration of the fortress. I brought back some open wines from my visit with Gilles for our lunch. Like me, he was encouraged by the results of Gilles’ first go.

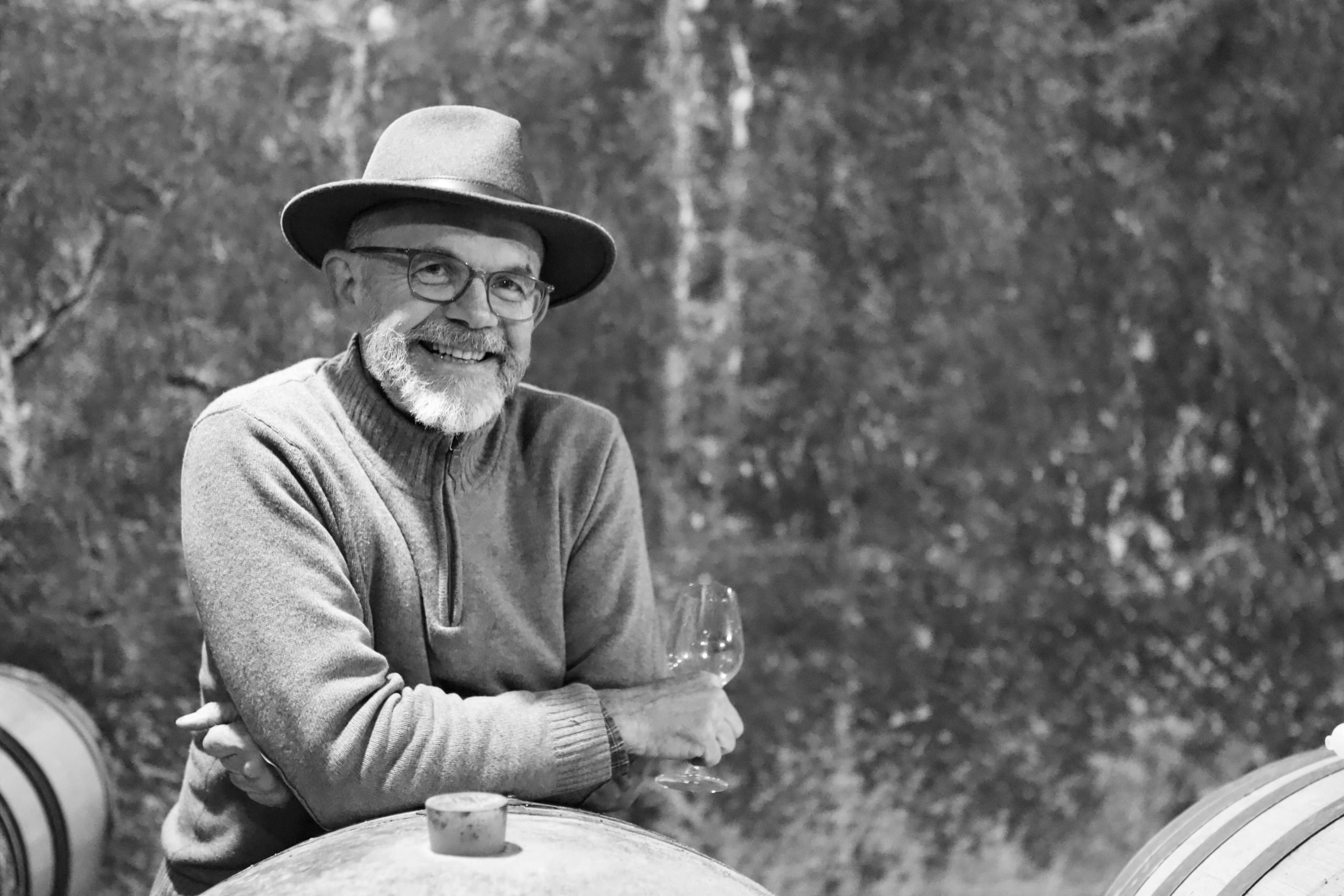

With a sparkle in his eyes and the animation of a great storyteller, the theatrical Gilles talks a lot about his infatuation with and the intriguing mystery of his new and much beloved castle. Rarely have I met a more gleeful and excited man in his sixties with such an overwhelming project that appears to need another entire lifetime to finish, though it’s scheduled for completion in five years (so it’ll probably happen in ten). The fortress is a bit run-down but not entirely neglected despite undergoing many centuries of war and damage. Empty and hollow today (with the exception of Gilles’ renovated quarters), this cold but gorgeous historical French castle from the twelfth century comes with a great patrimonial responsibility to restore it, of course, with the help and direction (i.e. control) from the French government.

During the first visit with Gilles I encouraged him to develop relations with Arnaud and to meet his talented and very thoughtful enologist, Olivier Barbou. Open to the suggestion, connections were made and now cellar visits are accompanied by Olivier and Gilles as they candidly navigate their way to find the voice of this talented terroir. Olivier has an open mind, experience and patience, a great match for Gilles’ enthusiasm, heart and great tasting-experience with a preference for the classic French wines of the Côte d’Or, Côte-Rôtie, Pommerol, and Jura. Together, they’ll focus on the terroir and less on technique. The combinations of Gilles’ professional expertise in organic farming (not only in viticulture but with the many greenhouses he’s owned over the years, with one still remaining), the obvious talent of his terroirs in Berrie and a great support staff, can only lead to compelling wines. His first year, 2019, already shows immense promise.

Saumur Rising

Saumur is a perfect terroir for Chenin Blanc, as demonstrated by the most recent exploits of growers in the southern end of the Saumur-Champigny appellation and just next to that in Brézé and Bizay, and even in the heart of the appellation much closer to the river. Cabernet Franc has its preferential spots where there is deeper clay topsoil above the shared tuffeau limestone bedrock, though the slightly colder climate and sparer topsoil make them a little more linear than the typical Saumur-Champigny—a profile we at The Source like very much. Saumur is also a very talented sparkling wine terroir with its hurdle in overall quality due to the demand and expectations for cheaper bubbles than more expensive ones from these parts. No one is willing to make a Champagne-level investment in the area to produce wines in the style of Champagne; they simply wouldn’t get the prices needed for the investment, even if the quality was there.

Tuffeau is one of the wine world’s great terroir rocks. Its chalky sandstone composition is very high in calcium carbonate content (though much lower than pure chalk or many of the different limestones in the Côte d’Or, for example) is its leading terroir expression asset (at least to this taster), while its high porosity makes it helpful to the vine in hot years with naturally higher water retention. The sandy element of tuffeau is a great contributor to the wine’s shape, often rendering them more “vertical,’ aromatically lifted, and with a lighter body in general when compared to harder rocks and denser topsoil. Tuffeau is similar to chalk, though it’s usually composed partially of sandy siliceous material eroded from the Armorican Massif, a Pangean remnant of highly acidic rock types west of Saumur in the greater Anjou region, and further west into Muscadet—other Pangean wine spots include the massifs of Iberia (including Galicia), Central France, and Bohemia, as well as all of Sardinia, most of Corsica, and part of Calabria. Over millions of years small volumes of these siliceous materials combined with ancient sea sedimentations rich in calcium carbonate, eventually compressing them into hard but lightweight tuffeau rock—about half the weight of granite—that are also a very reliable source for construction.

The further south into Saumur you go, the colder it gets. Of course this is only a generalization for all areas further from the river, but the Loire does help to regulate temperatures of those closer to it, as do all bodies of water and streams. Perhaps in the past Saumur’s general climate was too cold to produce substantial still wines from grapes ripe enough to build corpulent, powerful wines compared to other regions, though today it’s perfect for those interested in snappy, mineral-driven white and red wines. One only needs to avoid the flat areas of Saumur where the bedrock is mostly unreachable by vine roots through the deeply alluvial soils. In these lower sections, varietally expressive wines are made but are rarely great terroirs that layers on complexities and fine, minerally, refreshing textures to balance the intense acid profiles and taut fruit notes of Saumur. For Saumur’s top-flight terroirs, one must go higher (though in these parts are only slightly higher, like 30-50m up and rarely over 100m above sea level) where tuffeau is close to the surface for vine root access and the vineyards high enough to avoid the harshest conditions of spring frost, whereas the lower areas more often experience catastrophic frost events. Furthermore, most lower sections have lost all tuffeau close to the surface to deep erosion coupled with new depositions from elsewhere long ago.

The Vineyards

Twenty air miles south of Saumur city center and ten south of Brézé, lies Berrie, where Gilles lives in his childhood dream castle—man, if he had it when he was a kid playing “fort” with other boys, he would’ve definitely been the king between his friends! As with all ancient military outposts, FdB was strategically placed atop one of the higher hills in Saumur—the key to its spectacular terroirs with vine roots digging deep into the limestone-capped hill after relatively thin topsoil. (For comparison, the vineyards are about 30-50m higher on average than those of Brézé and much of Saumur-Champigny.) The topsoil here in each of the many adjacent parcels on the hillside have yet to be clearly defined vis-a-vis soil texture and the hierarchy of quality. We will know more in the future. How exciting!

The entire property houses 26 hectares, though 12.5 are under vine, with 2.5 of those recent replantings. The rest is forest and grain plantations below the vines, with six hectares now working with agroforestry principles, including almond, walnut, and other indigenous trees. The average age of the vines is around thirty years and most of the vineyard clonal selections rather than massale, like most of Saumur. Every region with a more recent history of poor prices for their wines, like Saumur, opted for clonal selections instead of massale when replanting because certain clones are much more productive. This history of quantity over quality is a challenge for the area. However, little by little more quality oriented genetic material will be planted in the region as Saumur growers aim for quality over quantity and are able to fetch prices to cover those costs. That said, the material of FdB demonstrates quality in the few examples thus far. There is depth to the wines, especially the Chenin Blanc.

The geological epoch of the bedrock in the area is mostly in what geologists refer to as the Upper Cretaceous’ Turonian, which developed between 94-90 million years ago. The bedrock is mostly yellowish tuffeau limestone—à la Clos des Carmes, the monopole cru of Romain Guiberteau that sits at the precipice of Brézé. Yellow tuffeau (note the yellowish tint on the rocks and walls of the cave) is known to be of marine origin, whereas white tuffeau is usually lacustrine, similar calcareous materials as the yellow but from freshwater. Yellow tuffeau takes its color from a greater iron content, thus hypothetically endowing the wines with a little more girth and power. The topsoil is a mixture of silt, sand and clay depending on the parcel, which were all deposited by flooding periods and mixed with what was unearthed from the underlying bedrock. It’s true that floods did a lot, even depositing a lot of orange and purple silex/chert on much of the flooded areas (though they likely have little to no influence on the wines’ taste from a nutrient/mineral standpoint because they are only a superficial topsoil element brought in from elsewhere), but human intervention has greatly influenced the topsoil composition through ripping with machines and regular plowing that breaks up tuffeau bedrock bringing it into the topsoil matrix, making it more easily erodible while clearing a path for roots to find the pure, highly calcareous bedrock more easily.

The Wines

Gilles hopes that his wines will be seen as authentic and with a pure voice of their terroir. He likes those that are “as light as clouds,” and wants them to be delicious and filled with pleasure. He mostly prefers wines with age on them, especially reds where the tannins have “melted” away. This Bretagne native with an inherent (as well as acquired) green thumb maintains his boyish romantic perception of wine and wants what he makes to be fine and thoughtful, more melodic than thunderous.

There are three main wines in Gilles’ initial range. In the future after much exploration with Olivier there will likely be a series of different parcel selections because of the variability of each plot, which there are numerous ones around the castle, and not contiguous in ownership.

The early wines tasted out of barrel (2021) and tank (2022) showed extremely well for someone so new to wine crafting, though he’s far from new to his own wine experiences and predilections. Of course Gilles has help from his team when he works in the vineyard and cellar, though there wasn’t much cellar work initially because he was only producing a few barrels of each wine while the remaining grapes were sold. The line is clear and precise. The Chenin carries a little bit of that Montlouis/Vouvray sweet and exotic grapey green and waterlogged, clean forest floor dampness, two qualities in Chenin that when done right are utterly alluring. The Cabernet Franc when on its own is like smelling and tasting black earth, wet green forest, wet gravel, and wild berries—classic in every way. In the first years it may be the better overall wine between white and red, but that position will surely be short-lived once the Chenin stands up a little straighter and its focus narrows.

The Crémant de Loire already feels like a “parcelaire” selection as a sparkling wine entirely from their Chenin Blanc plots rather than a mix of different communes as many others in the region are. This monovarietal crémant ferments in concrete for almost two weeks and is then aged further in concrete before bottling. The dosage depends on the year with the 2020 4g/L. In the future some base wine will be held back to supplement subsequent vintages to add more depth and texture.

Chenin Blanc on the property has an exciting future. In Gilles’ first years the approach was very basic but resulted in wines of clear pedigree and breed on the raw terroir material alone. Work in the cellar will be done to find its higher levels, and you can be sure the vineyard work under Gilles’ lifetime of training will deliver fabulous starting material to the cellar. You can expect the practice to change over the coming years, but in the first few vintages the Saumur Blanc “Coeur pour Coeur” is fermented for close to three weeks, partially in concrete to start and old wood casks (225l and 400l) to finish. Cellar aging is a minimum of one year before bottling. Malolactic fermentation is not intended, nor is it intentionally discouraged through higher doses of sulfites (the opposite of their goal to work with as little sulfite as possible as well as the avoidance of malolactic, when possible) or chilling down to extremely cold temperature; if it happens, it happens. The production level in the 2020 vintage was tiny and the domaine was in need of more wood. Some newer barrels will be peppered in over the coming years to fill out the cellar with good long-term aging materials free of the funk from other cellars. This Chenin, grown on a topsoil richer in clay has the structure and breadth to work well in newer oak barrels, though that’s not the overall long-term intention.

Even in Gilles’ first vintage, 2019, the entry-level red showed great promise. The 2020, though a much warmer vintage, was even better. Delicious and easy to drink, it’s Saumur Rouge with a smile and authenticity of place, even with its early renditions made principally of Cabernet Franc with a quarter of Cabernet Sauvignon—the vineyard arrangement left from the previous proprietor. The Saumur Rouge “Corps pour Corps” will be mostly Cabernet Franc with less, if any, Cabernet Sauvignon. The Cabernet Franc is macerated for almost three weeks on skins (the Cabernet Sauvignon for 8 days, mostly for a fruit grab rather than structure) with two pump overs during the first five to seven days and the following weeks before just a gentle hand-pressing of the cap to keep it wet and safer from developing unwanted levels of volatile acidity and potential bacteria. The first sulfite addition is made after the completion of malolactic fermentation. Sulfite levels will continue to decrease year after year with the goal of using no more than 50ppm.

Photos and copy owned by The Source Imports

Forteresse de Berrye - 2020 Saumur Blanc, ‘Coeur pour Coeur’

Out of stock