Sette

This website contains no AI-generated text or images.

All writing and photography are original works by Ted Vance.

Short Summary

Gino Della Porta and his close friend and superstar-enologist Gian Luca Colombo founded Sette in 2017 with the purchase of a 5.8ha hill in Bricco di Nizza, in Nizza Monferrato. They join the new generation of driven young winegrowers who experiment with new and ancient techniques to express their vision of wine free from cultural and regional expectations while employing the most ecological methods possible. Certified organic since 2018 and in conversion to biodynamics in 2020, their terroir is composed of sandy limestone, chalk, and a wide variety of other siliceous geological formations on steep hills with great variations of soil grain. Their broad range includes dry, skin-contacted Moscato and amphora-aged Grignolino, and their main focus is their Barbera d’Asti DOC (though technically in Nizza DOCG) and Barbera Nizza DOCG from 80-year-old vines. There are no rules or cellar recipes beyond appellation requirements and every season determines their strategy,Full Length Story

The Monferrato/Asti area is Piemonte’s new wine laboratory, and experimentation is particularly extensive at Sette, where they’re looking to expose new dimensions of their local indigenous varieties. The comedic and talented duo that includes the experienced wine trade pro, Gino Della Porta, and well-known enologist, Gian Luca Colombo, founded Sette in 2017 with the purchase of a 5.8-hectare hill on Bricco di Nizza, in Nizza Monferrato. Immediately, a full conversion to organic farming began, followed by the implementation of biodynamic techniques in 2020, the latter being a vineyard culture still considered somewhat radical in these parts. The wines are crafted and full of vibrant energy with focus and only a soft polish. There’s the slightly turbid and lightly colored, juicy, fruity, minerally Grignolino, and their two serious but friendly Barberas, among other goodies that will trickle in with time. Sette’s game-changing, progressive approach and delicious wines (with total eye-candy labels) should ripple through this historic backcountry and bring greater courage to the younger generations to break out of the constraints of the past and move full throttle into the future.

Barbera in Chablis?

My first interaction with a wine from Sette was at a restaurant in Chablis. I accompanied Romain Collet, one of the two Chablis producers we import, to an invitation from Jasper Morris, the well-known Burgundy writer and author of the exhaustive reference book, Inside Burgundy. We were met by three other young Chablis producers who’d been invited to Jasper’s tasting, which involved some filming and was to be televised on a British network. After the filming, the restaurant owner offered everyone a blind taste. As an unexpected invitee, I kept silent while the growers stretched to figure out the wine. Hanging with the film crew, seizing the opportunity to talk about their artistic métier. The standoff started gently. “Seems like a Burgundy…,” one timidly said. Another took it further, “It could be from Corton, or maybe Pommard.” Back and forth, they dug into Burgundy’s limestone and clay terroirs, but the acidity was impossible for Burgundy, and the color a stretch.

Ink-black with red trim, and deeply complex, its full and tense acidity and focused flavor was impressive. No sign of new oak—another affirmation that mostly ruled out Burgundy. Quickly it began to reveal its hand to me, the nearly indescribable mark of a Piemontese red, a note all Piemontese junkies know. Once I’d landed on Piemonte, the dominoes instantaneously fell. Leaning over to one of the film guys, I whispered, “It’s not Burgundy. It’s Barbera.” A bottle with a gorgeous Asian-inspired piece of modern art for a label (pictured above) was revealed to disbelief followed by a flurry of the uniquely constructed onomatopoeia only a native French speaker can say without sounding vulgar or pretentious. They were impressed by the wine, and so was I. Keeping quiet, I intended to tuck this rare blind tasting victory in my back pocket when the film guy pointed at me and announced, “That’s what he said!” Well, occasionally lightning strikes. After a quick search on Instagram, I made contact with the producers and the rest is, well… you know.

The “Old Couple”

As a self-described “old couple,” the dynamic duo, Gino and Gian Luca have great chemistry; longtime friends that flow naturally together, one finishing the other’s thoughts, often teeing up the start of a joke for the other to smash with his driver, on cue. Gino Della Porta, born in 1973, sports the big hipster beard known as a Garibaldi (a term I only recently learned). Mellow like The Dude and constantly wearing a sheepish smile, he’s always ready for the next punchline. A resident of Pisa, he does the long commute to Nizza for cellar movements, important work in the vineyards and during the harvest. Originally from a small village about seventy kilometers north of Rome, he moved to Pisa for university. He fell in love with this Tuscan city famous for its tower, became a sommelier in 1997 and then opened a comic book shop (1998-2003)—a man after my own childhood, which also involved a comic-book addiction that was also replaced by wine. (Gino admits that his interest in comics and superhero art heavily influenced Sette’s beautiful labels.) In 2003, he started selling wine for one of Italy’s new-wave importers/distributors followed by working with one of the most important Italian importers from 2010 to 2017. He also developed a small company that manages marketing and sales for a few very recognizable Italian estates, like Le Boncie and Cappellano. Inspired by his past work with the old vintage Barbera wines of Trinchero and Scarpa “La Bogliona,” he and Gian Luca bought a perfectly situated 5.8-hectare vineyard in Nizza, and Sette was born.

A fast-talking, thoroughbred enologist with an ever-present mischievous grin ready to pounce on the next gag with Gino, Gian Luca Colombo’s Barolo client list is long and diverse, with names like Reva, Diego Conterno, Garesio and Castello di Perno. His early exploits include top prize as the first recipient of the “Gambelli Award for Best Young Italian Enologist,” in 2014, and in 2011 he started to bottle his own miniscule production of wines made in the cellar underneath his house. In 2017, his organic and biodynamically farmed Segni di Langa – Gian Luca Colombo project was labeled and his cantina was made official.

One Vision

Gino and Gian Luca have different skill sets but their vision for Sette is clear: to make wines free from cultural and regional expectation while using the most ecological methods possible inside organic and biodynamic culture. Constantly pushing Gian Luca to further open the throttle on experimentation, Gino explains, “We know we have to produce naked Barbera that explains our terroir, but we have to experiment to find our way.” He also knows this generation of wine professionals and consumers are the largest collection of the most open-minded supporters of experimentation in the history of the wine business. G and G know that they also must adapt traditions to today’s circumstances; the climate isn’t what it used to be, and neither is the interest of the market; they don’t need to reinvent the wheel, just adapt it to our times. While some wine regions (temporarily) benefit from climate change, from one year to the next, others yield grapes with increasingly more underdeveloped tannin and acidic balance than in the past, so traditional methods of farming and cellar techniques must adapt. Some wines of just two decades ago, though made the same way today, have changed dramatically.

“We found our vineyard deeply disfigured and strongly oriented toward large-scale production. There was an extensive use of chemical fertilizers, herbicides, and systemic products. For the whole of 2018 and 2019 we avoided intervening in any way, to ensure that the vineyard cleans itself of the excesses of product given in these years.”

In 2019, the beginning of their third year, the second season under organic culture, they planted various cruciferous plants to help clean and regenerate the soil. Despite the dilapidation of the neighboring vineyards, it’s one of the few in the area where it’s still possible to find tall trees and fruit trees. Gino and Gian Luca intend to increase their efforts in recreating a more natural environment with the additional planting of more than forty regional trees (some fruit-bearing) that will further improve its biodiversity.

Monferrato: Piemonte’s new wine lab

Wines from Sicily, Campania, Liguria, Abruzzo, Lombardia, Valle d’Aosta, and even many parts of Piemonte, like Alto Piemonte, existed in relative obscurity up until less than a couple of decades ago. Recession in the late 2000s forced restaurants with deep cellars into a selloff. Furthering the movement toward smaller producers were the reduced budgets restaurants now had as they tried to return to normalcy and refill their cellar bins. They also shifted to much shorter lists with constantly changing selections, which not only opened the doors for those boutique Italian wine importers who had previously tried and failed to break in, but also for young and hungry new importers, like us. To support the uprising and force customers to venture away from Chianti, Brunello, and Super-Tuscans, some Italian restaurants even purposely began to leave them off of by-the-glass lists (and a few off their lists altogether), explaining that if they had a Chianti by the glass it would sell 80% of the time, leaving many other reds to lose their best qualities before the end of the bottle. The indigenous Italian wine market cranked into full boom and it’s no longer a movement, it’s now an establishment.

The wine world has gone completely mad on pricing. Elite and micro-producer prices are embarrassingly stupefying and never worth it (unless money is not a concern), and the wine world’s quietly kept secrets once whispered only among the trade are a thing of the past, seemingly for good. Piemonte’s Langhe wine regions have had a severe uptick in interest and investment in recent years, along with many other European wine regions. Only ten years ago it was easy to procure big-name wines, like G. Contero, G. Rinaldi, G. & B. Mascarellos, and even Burlotto, a readily accessible and inexpensive Barolo that recently jumped in price about 500% (on the secondary market) once one of their 2013s was awarded a perfect score by a wine critic. Many greats of the Langhe seemingly snuck right out of reach in only a couple of years for those of us with modest and medium budgets, just as Burgundy did more than a decade ago. These unwelcome departures left our thirst for the noble tastes and particular house styles unquenched. Truly great Barolo and Barbaresco can still be found at fabulous prices (take Poderi Colla, for example), but there are so many with medium to high prices that are more likely to underdeliver than live up to expectations.

However, today is not a time solely for lamenting the loss of easy access to today’s elites. The horizon is always full of new arrivals from forgotten or overlooked lands that once shined with success before falling out of sight, many of which were showered with praise by the royalty of old, their noble grapes preserved by generations of working-class heroes. With the price increase crisis of the Langhe followed by that of Alto Piemonte, how can any other Piemonte region compete in quality with Barolo, Barbaresco, and the wines of Alto Piemonte?

Monferrato is primed for a breakout performance. But how exciting can Monferrato possibly be? Does the market even take this region seriously? These were regular thoughts when we first began to focus on importing Italian wine in 2016. Prior to that, our company brokered Italian wines in California for almost a decade with a few different Italian importers. The importers we worked with played a quiet but influential role in the emergence of backwater Italian wines. Each had their token price-point Monferrato producer or two, usually a couple Barbera d’Asti, but not much more.

We never set out to plant a big flag in the Monferrato/Asti area. Like the Italian wine importers we once worked with, we were in search of our token Asti producer to supply us with some value Barbera. Then something that we’ve seen many times before happened: we saw big potential that only needed a strong and friendly nudging.

Monferrato advantages

Monferrato’s first advantage has to do with certain expectations about the wines they produce that differ from more famous Piemontese regions, one of the more pertinent being the expectation that they should be cheaper than those of the Langhe. Most importantly, many don’t play the Nebbiolo game, so they don’t have the burdensome weight of navigating the terrain of today’s grape royalty. Nebbiolo-land comes with familial and regional baggage. The iron grip of the most recent generational lines that built the family up from the poorest area in Italy to one of its wealthiest isn’t keen to let the kids wander too far off the path. Ok, they can tinker with Dolcetto, or even Barbera, but Nebbiolo used for their Barolos and Barbarescos? The vignaioli of Barolo and Barbaresco with the big critical press are no longer just grape farmers and winemakers, they’re businesspeople first, and their task now is to push the same game piece, the same direction, every vintage.

Monferrato has their own historical grapes, which means they won’t always be second or third-division Nebbiolo land. They can be first-division in Barbera, Freisa, Ruchè, and what I believe could be the most significant category uptick, they undoubtedly will be first-division Grignolino—a variety that was considered grape royalty for centuries.

Another advantage is that they have the terroir with enough talent to go beyond “good value wine” and into a world-class product. The ingredients are there: limestone and chalk with extremely active calcium, sandy limestone, a great variety of other geological formations, gently sloping hills (preferential to steep ones with looming climate change toward hotter temperatures and the need for better water retention) with great variations of soil grain to put grapes on their most favorable soil types (Grignolino on sand, Freisa on clay, Barbera in the middle), tremendous biodiversity with swaths of indigenous forest between vineyard parcels and sometimes right in the middle of them along with a multitude of intended crops (well beyond the occasional hazelnut grove as seen in much of the Langhe’s prized vineyard areas where grapes aren’t suitable), and a climate that’s conducive to organic and biodynamic vineyard culture.

Monferrato’s freedom from preconceived notions can lead to freer thinking within the community. Freer thinking leads to greater experimentation. Experimentation leads to breakthroughs. Breakthroughs change the game. When games change, people follow.

The x-factor here could be that Monferrato’s growers surely include ambitious and creative kids with dreams to build. Their parents and grandparents lived in relative isolation in this Italian backcountry while other nearby regions went from poverty to wealth in a single generation. Many of the Gen Xs are in the family driver’s seat now, the Millennials are working side by side with mom and dad, the Zoomers are at school, and all three of these generations are exposed to the world around them through their social media feeds, so they’ve witnessed the incredible success of Langhe. They see that their northerly wine neighbor Alto Piemonte is not only rising, but it has also arrived in a big way. They realize the potential of the natural wine movement and many will want a piece of it (but do it cleanly, please!). There are now openings to make whatever style of wine they want because there are fewer shackles; they can stay and improve on the traditional course passed down for generations and/or get creative in their own way and veer from the status quo. Whatever the path they choose, they will likely have more freedom than the average kids of Barolo or Barbaresco, probably even more freedom than any other Nebbiolo-focused region.

Another factor is immigration, and I don’t mean people from other countries, but those from neighboring Langhe. With the increase in frequency of the Piemontese selling their most prized vineyards to foreign investors for fortunes nearly impossible to recoup in the wine business (without flipping it again to another high-bidding trophy hunter), how does any financially challenged Langhe youngster, from a family that works for the landowner or in the cellar, filled with inspiration and great knowhow get out of first gear? They have to move. This is what spurred Gian Luca to partner up with Gino to play ball inside of an appellation with tremendous talent that was still financially attainable, and with a lot of great underutilized sites waiting for the right new owners. Of course, Gian Luca has his own Barolo project, but expansion has proven to be financially prohibitive.

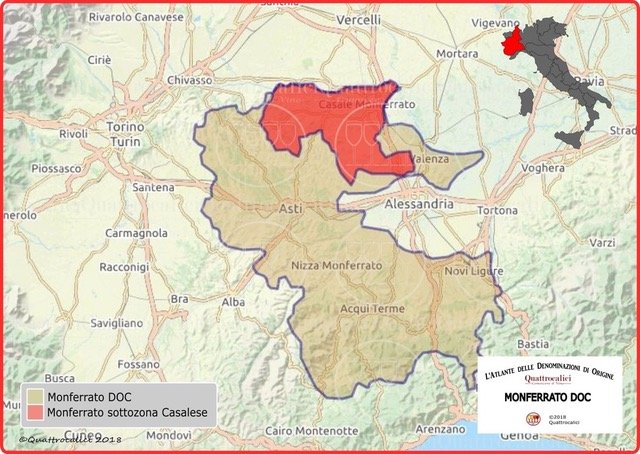

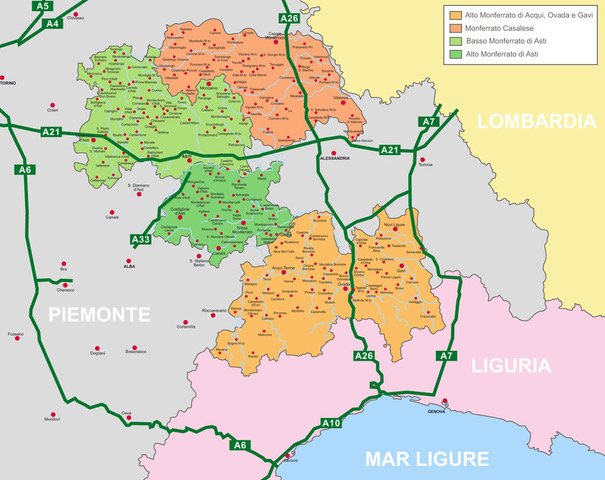

Monferrato DOC

Monferrato can be confusing. First governed by Aleramo, the Marquis of Montferrat, who also controlled Liguria, Monferrato is a historical area established around 900 AD. Its historical borders are approximately the same today, although they are informal and cross into both the Asti and Alessandria provinces. Entirely within the Alessandria province in the north and eastern side of Monferrato is Monferrato Casalese, and in the far south, bordering Liguria’s northern border, Alto Monferrato di Acqui, Ovada e Gavi. Inside of the Asti province, on the northwestern side is Basso Monferrato d’Asti, and in the center, Alto Monferrato d’Asti.

Inside of Monferrato there are many different DOCs and DOCGs, and many overlap between the two formal provinces, Asti and Alessandria. The Monferrato DOC is quite flexible, and one can produce about anything they want with this generic DOC on the label (e.g., Monferrato DOC Nebbiolo, Monferrato DOC Barbera, Monferrato DOC Chardonnay, Monferrato DOC Rosso, Monferrato DOC Sauvignon, Monferrato DOC Pinot Nero, etc). It can come from different areas inside Monferrato (sometimes overlapping the formal provinces, as Barbera d’Asti DOC does) from different terroirs with very high yields. The largest part of the wines produced in this general DOC have a very low price and are often from yields of 9,000-11,000 kilos of grapes per hectare.

Monferrato’s Barbera d’Asti DOC covers roughly two-thirds of the area, overlapping the two provinces (all of Asti, and mainly a small part of Alessandria with the highest hills). Similar to Monferrato DOC, Barbera d’Asti is often produced in higher volumes per hectare than other more quality-focused appellations, with an annual maximum of around 9,000kg per hectare/~4.5 US tons per acre. They are also often picked from numerous sites with different soils, expositions and terroirs. Wines labeled as Barbera d’Asti must be a minimum of 90% Barbera.

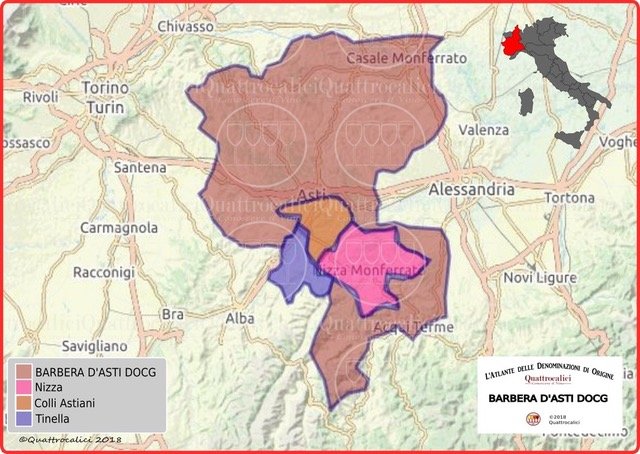

Nizza DOCG

According to many knowledgeable wine professionals specializing in Italian wines, Nizza is home to the world’s most complex Barbera wines. Located inside of the greater Barbera d’Asti DOC and inside of the Alessandria province, Nizza became the most recently established DOCG in Italy (2014); formerly it was known as Barbera d’Asti Superiore Nizza, which was established in 2008 as a sort of sotto zona, similar to France’s lieu-dit. Located in the southeast area of the Barbera d’Asti DOC, it borders to the east Colli Astiani DOCG and Tinella DOCG.

Gino explains that Nizza’s DOCG creation was the result of many factors. Perhaps the most relevant being that it was a historically famous area for the quality and aging potential of Barbera; many old Nizza Barberas aged as well as Langhe’s great Nebbiolo wines. Only fifty years ago, or so, it was difficult to get Barbera to ripen fully, but Nizza had an edge over other Monferrato areas with Barbera because of its slightly higher temperatures and more arid conditions due to the southern winds from Liguria’s Genova area. Inside of Monferrato, Gino guesses that the temperatures during the growing season would be about 1-1.5°C higher than most of Monferrato, and the nights remain warmer—that latter a crucial element for ripening Barbera due to its large berries, thin skin and compact bunches.

Another reason for the creation of Nizza DOCG (and its neighboring DOCGs, Colli Astiani and Tinella) is surely a result of the loose regulations and quality controls of the Barbera d’Asti DOC where many will naturally make quantity-over-quality wines—not only because it’s easier, but because the financial incentive is not there yet for the entire appellation to prioritize quality. While the Barbera d’Asti DOC wines can be grown on all expositions, Nizza DOCG is limited to vineyards with southern expositions (SE, S, SW) ranging in altitude between 220-300m. Nizza DOCG’s alcohol minimum is 13%, production limits are 7,000kg/hectare (although for young vines there are lower minimums in the first years of production), Barbera must constitute 100% of the wine, 18 months minimum cellar aging with no less than 6 months in wood, and 30 months of aging for Nizza DOCG Riserva with a minimum of 12 months in wood. Producers inside of the Nizza DOCG always have the option to make Barbera d’Asti DOC from their Nizza vineyards, which Sette does with their Barbera d’Asti all grown in Nizza.

In Nizza’s three valleys, the northern part is richer in sand and the southern is richer in clay. Wines with the greatest potential—from a general perspective—are mostly grown with a greater balance of these two soil structures. As we learned from La Casaccia, one of our Monferrato growers inside of the Monferrato del Casalese DOC, they plant Grignolino on the top of hills in their area where the soil is more sandy, Friesa on lower sites where there is more clay, and Barbera in the middle where sand and clay are more mixed.

Grapes and Wines

Despite its non-native status in Monferrato, Barbera is the local sheriff and the breadwinner. Apparently, the variety originated in southern Italy centuries ago (perhaps Sicily or Campania, but the debate about its origin and actual arrival to Piemonte is still alive) and began its mass proliferation sometime after phylloxera hit in the mid- to late-1800s. Today, it’s ubiquitous in much of Piemonte where it holds top spot in total production among red grapes. The good news is that there is a lot of it in the marketplace, which, thankfully, keeps the prices down, even from producers in Barolo and Barbaresco.

Barbera is indeed a bit of an outsider in Piemonte. It’s somewhat easy to spot in a blind tasting of Piemontese wines because of its abundance of acidity and lack of tannins—the exact structural inverse of Dolcetto, which maintains higher acidity than Barbera does tannins. Barbera also typically requires a greater alcohol percentage to achieve phenolic ripeness that moves it away from hardened tannins (the few that it has) and the potential for unbalanced, high acidity. Uniquely suited for its best results with warm summer weather during the daytime and nighttime makes it the opposite of the other Piemontese grapes that need the daytime heat but colder nights to reach their heights—another clue to its possible origin from the south where day and nighttime temperatures don’t fluctuate like those in the north or deep inside the Apennine range.

Sette produces two different wines made entirely of Barbera grown inside the Nizza DOCG, within the comune Nizza Monferrato (from the same 5.8ha plot that’s been under organic conversion since 2017 and biodynamic culture since 2020), on a south face composed of calcareous marls and sandstones. One is bottled as Barbera d’Asti DOC, made from vines of 20 to 40 years old, on chalk and sandstone, with a yield no higher than 5,500kg/hectare (~2.5 US tons/acre), and the Nizza DOCG from mostly 80-year-old vines on sandstone, limestone and chalk. For both wines they use an old Piedmontese winemaking technique of waiting for the must to reach 10-11 degrees of alcohol and then use a wooden grid to submerge the cap for a gentler infusion for the latter two-thirds (or more) of the maceration time to softly extract while the wines reach their textural balance as it is tasted daily. This process lasts between 30 to 50 days, depending on the vat and the year, with Nizza always a bit longer than the Barbera d’Asti.

Following the pressing, the Barbera d’Asti makes at least a year of aging in the cellar with concrete vats prior to bottling and release, while the Nizza is aged for a year in a 30hl Stockinger Austrian oak barrel followed by six months in concrete. The result for both of these wines is a softer structure than the typical Barberas from the Langhe, but also with more savory notes and more profound depth. Sette’s Barberas are extremely serious wines with massive potential; they’re on the more technically tight craft side without sacrificing their approachability and friendliness.

Gino was inspired to include Grignolino inside their range by the Grignolinos made by one of our other producers, Mauro Spertino, from Cantina Luigi Spertino. Gian Luca admitted initially he was not a fan of Grignolino until he made his first one. Like many of us, he fell in love and is excited about his future tinkerings with this enchanting Piemontese queen.

Ideal for those in search of lighthearted but authentic and terroir-rich wines, Grignolino offers the classic cultural tastes and smells of Piemontese wine. Lightly colored but substantive and aromatic, it’s enticing and reminiscent of fresher vintage Nebbiolos with those unique x-factor-rich Giuseppe Mascarello-red tones but mostly with a much lighter hue. It seduces with constant emissions of pheromonal scents of dainty, sweet red and slightly purple flowers, tart but just ripe berries and a little flirt of that indescribable but inimitable Piemontese red wine spice and earth. Simply made Grignolino is invitingly poundable, delicious fun, but in more intimate encounters its interior strength reveals firmness, respectability, nobility.

Navigating this charming grape in the vineyard and cellar requires consciousness about its thin, pale red skins and its contrasting tannin-rich seeds with a higher seed count than other Piemontese grapes. One answer for tannin management is to employ shorter macerations with pressing once the interior grape membranes break down, but prior to fully exposing the seeds to the alcohol when the extraction of these harder tannins can happen. With this approach, one can also pick earlier to highlight the variety’s natural charm with an even redder, crunchier spectrum of fruit ripeness—a hallmark characteristic that often serves this wine better than those with more wood contact and ripeness on the vine. All of this makes for a wine with a lot of pleasure while retaining its regional characteristics.

According to Ian D’Agata in his book, Italy’s Native Wine Grape Terroirs (a must for anyone serious about or interested in Italian wine), the Grignolino wines were prized as far back as the thirteenth century, but lost favor in the last thirty years and were replanted with other grapes that had a stronger market value in the Langhe and elsewhere. D’Agata pushes the merits of Grignolino and loves the wines, and we understand why. Grignolino seems to have all the ingredients to really thrive in today’s market, one that’s more than willing to pay for the highest levels of nobility and extremely fine subtlety. If Grignolino had held court in prized Langhe vineyards that with today’s swing for many from power to elegance, it may have held the number two spot just below Nebbiolo, leaving Barbera and Dolcetto to duke it out for third. It seems that Grignolino can be that good but clearly within the more gentle wine context.

In these first years of production (starting with the 2020 vintage), Sette’s Grignolino is made from fruit purchased from an organic grower. It’s bottled intentionally turbid after a couple of weeks of gentle fermentation and then eight months in Tava amphoras. With the gentleness of the tight-grained amphora, the delightful turbidity and having grown on calcareous sandy soil vineyards replanted twenty years ago, the wine takes on a lightly creamy texture and body resulting in a more playful interaction led by its vibrant energy. (Tava amphoras are cooked at extremely high temperatures which tightens the porosity significantly over those cooked at lower temperatures, leading to customized micro-oxygenation level for Sette’s amphoras that have similar porosity to that of a 15/20hl oak barrel, while imparting no taste to the wines.) Riding the line between well-polished and medium structure and texture, this finely tuned Grignolino is fun in a bottle, just like the owners of their project.

We know Moscato as a still wine is a hard sell. Under Sette’s approach, the annoying, cloying characteristics of Moscato are absent and all that’s left are its most flamboyant traits, toned down by its eight-hour skin contact before fermentation, its aging in Tava amphoras, and its inviting and light yeasty haze. There are so many pleasantries it’s hard to dislike, even if it’s not your typical style. Stylistically, with its floral and gentle spice notes, and texture similar to unfiltered sake, there may not be a much better pairing for nigiri sushi, a perfect match for sticky rice and raw fish with ginger and wasabi. The vineyard comes from two different plots, one with twenty-year-old vines and the other with eighty years under its belt.

Geology: Monferrato

(The geology sections are researched and compiled from various sources by MSc Geologist, Ivan Rodriguez)

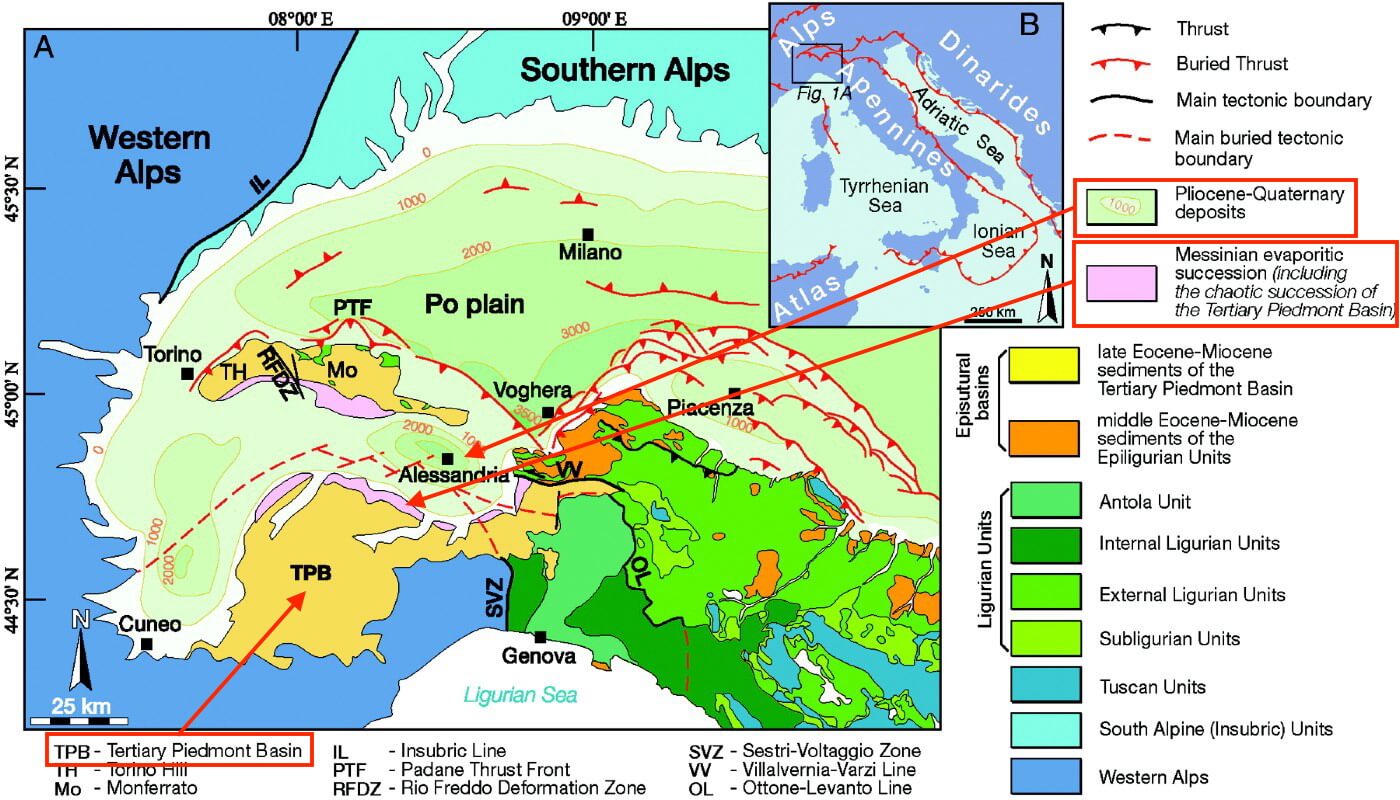

Like most geological stories, Monferrato is complex. To simplify as much as possible, Italy’s Piemonte region has many components related to the Alps-Apennines orogenic (mountain building) system. We could consider four general divisions: Alps and Alpine foothills, Alpine Glacial-related deposits, Apennine Mountains, and the Central Piemonte hills. While the latter two have relation to Monferrato, the most important to this area and to the wines of Sette is the Central Piemonte hills.

When thinking of Monferrato, its gentle hillsides come to mind, and they are grouped into two general sets in central Piemonte. One has higher, steeper hills, and geologically corresponds to the Piemontese Tertiary Basin, and the lower, more rounded hills correspond to the Pliocene Southern Succession.

Hill shape is important and partially explains a soil’s water retention capacity (another important component being soil composition): steeper hills have lower water retention and greater erosion than more gradual hills. A vine’s access to water greatly affects the balance of its wines, including components like alcohol content, tannin and acid balance, and all of its flavor components. In the past, extremely steep vineyards were often considered an asset with regard to quality, but as visually impressive as they are, the increasingly excessive heat caused by climate change is moving them toward liability status.

Within the grouping of Piemontese Tertiary Basin’s higher, steeper hills are four groups: 1) In the north, a ten-kilometer-wide band between Torino and Casale Monferrato including the northern half of Basso Monferrato and Monferrato Casalese, with the surrounding appellations of Torino on the western border of Monferrato; 2) the Langhe, a series of hills south of Torino, on the western border of Monferrato; 3) Alto Monferrato hills between Nizza Monferrato and the Ligurian mountains, known as part of Alto Monferrato d’Acqui, Ovada and Gavi; and 4) the Borbera-Grue (hills between the rivers, Borbera and Grue) at the southeasternmost part of Piemonte, and the easternmost part of Alto Monferrato d’Acqui, Ovada and Gavi.

The second grouping of the Pliocene Southern Succession’s more rounded hills are enclosed in the south by the Tanaro River and Nizza Monferrato area and, in the north, by Chiero, Moncalvo and Alessandria. It covers most of Alto Monferrato d’Asti and the southern half of Basso Monferrato and Monferrato Casalese.

The geological history of these two groups starts with the collision of the European and paleo-Adriatic tectonic plates, which resulted in the Alpine Orogeny that formed the Alps and Ligurian mountains (among others). During this process, today’s Monferrato area was a sea that was progressively uplifted by the activity of the Alpine Orogeny and began to separate from the Mediterranean by the uplifting of today’s Ligurian Mountains to the south, leaving the only opening toward the east through today’s Po Valley. Eventually the Mediterranean Sea disconnected (about six million years ago) from the Atlantic Ocean and gradually dried out in what is known as the Messinian Salinity Crisis. This event left a footprint in today’s deposits as a layer of gypsum found all over Monferrato, which marks the limit of the Piemontese Tertiary Basin and the beginning of the Pliocene Southern Succession. At the same time, the uplifting of the Piemontese Tertiary Basin (today’s Monferrato Hills, along with other nearby elevated areas, like the Langhe) due to the still active Alpine Orogeny, isolated several areas that became restricted basins that then captured these mostly terrigenous sediments (erosion of materials from land, mostly non-marine sediments), weathered from the surrounding Ligurian and the Alpine ranges. One of those was the Pliocene Southern Succession, which acted like an inner sea until the sediments filled the basin, sometime less than 2.5 million years ago.

These uplifted areas of Monferrato have an extensive range of sedimentary rocks developed between 38 and 2.5 million years ago, like terrigenous rocks as sandstones and mudstones, and marine sediments rich in calcium carbonates, like limestones, marls, etc. When comparing the sediments within the Piemontese Tertiary Basin, several differences can be addressed. In general, the calcareous content of the formations in the northern hills of Torino and Monferrato are more frequently present than in the south, according to a predominance of marlstones and sandy marlstones (e.g., Antognola, Cessole, and Pietra de Cantoni formations). In the south, in Langhe and Alto Monferrato, there is a predominance of sandstone and mudstone units without excluding a calcareous presence in some areas.

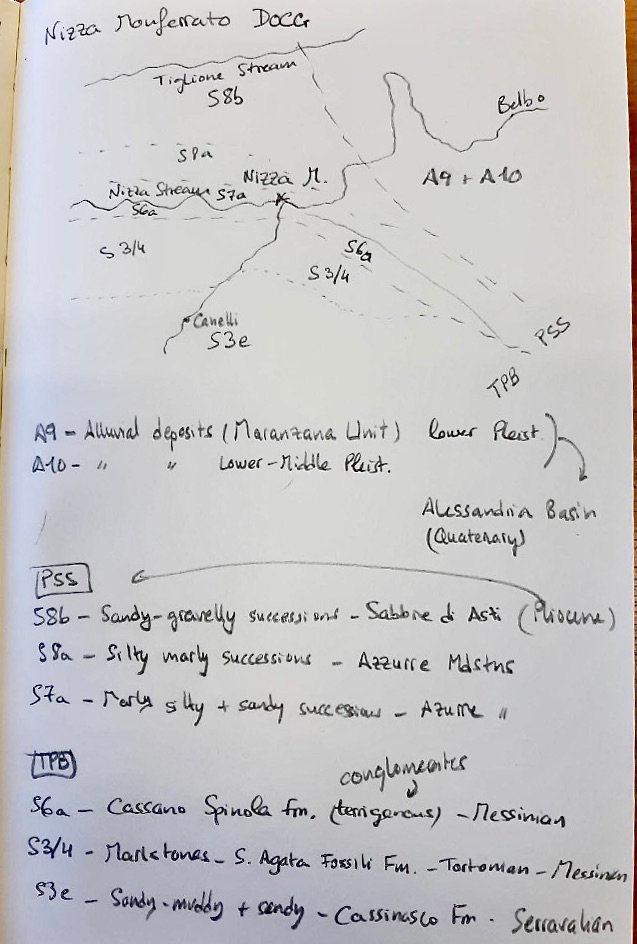

Geology: Nizza

Nizza lies over two geological units previously mentioned, the Pliocene Southern Succession (low, rounded hills) and Piedmont Tertiary Basin (steeper, higher hills). Vineyards in its southern sector correspond to the Pliocene Southern Succession and are a mix of sand, gravel, and silty marls. Closer to Nizza Monferrato the bedrock and topsoil is largely composed of terrigenous (mostly non-marine) conglomerates. Toward the south, marlstones from the S. Agata Fossili Formation are predominant. Close to Canelli, the Cassinasco Formation is predominantly sand, and sandy-muddy deposits. The northern sector of Nizza Monferrato and north of town, the vineyards correspond to the Pliocene Southern Succession (Asti and Azurre formations), and are deposits mainly formed by sand, gravel and silt. However, in the northern banks of the Nizza stream (NW Nizza Monferrato) also present marlstones (clay/calcium carbonate rock). A third sector could be differentiated in the northeastern part of the appellation and is composed of more recent alluvial deposits from the 2.5 to one million years ago.

Geology: Sette

Sette’s vineyards are over two main geological formations. The first (and predominant), the Argille Azzurre Formation (three to five million years ago) composed mainly by marine mudstones but also with a significant presence of marls and terrigenous sandstones. The second is the Vena del Gesso Formation, which is mainly formed by the gypsum derived from the Messinian Salinity Crisis. However, the areas where this formation is dominant is mostly shale, indicating a marine environment depleted of oxygen, being the prelude of the drying out of the Mediterranean Sea (six million years ago). Sette’s Nizza Monferrato vineyards on Bricco di Nizza is located in between these two formations, so a variety of rocks, including mudstones, marls, sandstones and gypsum can be found.

Geological references:

Festa, A., Codegone, G. (2013). Geological map of the External Ligurian Units in western Monferrato (Tertiary Piedmont Basin, NW Italy). Journal of Maps, 9(1), 84-97.

Gelati, R., Gnaccolini, M. (1982). Evoluzione tettonico-sedimentaria della zona limite tra Alpi ed Appennini tra l’inizio dell’Oligocene ed il Miocene medio. Memorie della Società Geologica Italiana, 24, 183-191.

Piana, F., Fioraso, G., Irace, A., Mosca, P., d’Atri, A., Barale, L., Falleti, P., Monegato, G., Morelli, M., Tallone, S., Vigna, G.B. (2017). Geology of Piemonte region (NW Italy, Alps–Apennines interference zone). Journal of Maps, 13(2), 395-405.

Sette - 2024 Vino Bianco

Out of stock

GROWER OVERVIEW

Italian import consultant and brand manager for many significant Italian producers, Gino Della Porta, and his close friend, superstar-enologist Gian Luca Colombo founded Sette in 2017 with the purchase of a 5.8ha hill in Bricco di Nizza, in Nizza Monferrato. They join the new generation of driven young winegrowers who experiment with new and ancient techniques to express their vision of wine free from cultural and regional expectations while employing the most ecological methods possible. Certified organic since 2018 and in conversion to biodynamics in 2020, their terroir is composed of sandy limestone, chalk, and a wide variety of other siliceous geological formations on steep hills with great variations of soil grain. Their broad range includes dry, skin-contacted Moscato and amphora-aged Grignolino, and their main focus is their Barbera d’Asti DOC (though technically in Nizza DOCG) with a vine age of 20 to 40 years old, and Barbera Nizza DOCG from 80-year-old vines. There are no rules or cellar recipes beyond appellation requirements; every season determines their strategy, where some years the Nizza has eight days on skins and other years nearly 60 days, followed by variations in aging between 30hl Stockinger barrels, concrete vats and Tava amphoras. The wines are neither fined nor filtered.

VINEYARD DETAILS

Sette Bianco is harvested from Moscato vines planted in 2002 on a steep north-west slope between 250-280m on marly bedrock with deep silt and calcareous topsoil.

CELLAR NOTES

Sette Bianco has 2 days of skin maceration before its natural fermentation up to 16-18°C in steel until reaching 10% alcohol. It’s then transferred to Tava Amphora to finish fermenting where it’s aged 9 months with the first sulfites added after malolactic fermentation. It’s neither filtered nor fined.