One of the most compelling qualities about David Croix is his directness. He answers all questions candidly, no candy-coating, no embellishment. His wines have similar qualities; they’re honest and straightforward. Respectful. There’s only beauty coming from the wines made from this estate. And joy—the joy of realizing possibilities.

David Croix, like many other Burgundians his age, is always on the move. In the early years, his wines were by his own description: “Darker and tighter in the past.” He says that now the vines have changed and so have the wines. The fruit now is brighter and more expressive, and the wines more fun to taste when young. The domaine’s conversion to organic culture in 2008 is now really starting to, well, bear fruit… Those secondary and tertiary components mentioned earlier began to take on more of the wine’s expression naturally. Perhaps it was the vines that influenced David’s style, not the other way around? Today, he believes that there is more natural balance in all of his wines.

A Brief Story &

Details On The Wines

Regarding red Burgundy, the two appellations David’s Domaine des Croix is focused on seem to be thought of as second or third fiddle within their classification. Beaune’s premier crus are often placed in the middle to lower end of the totem—surely from all the Côte de Nuits’ main appellations. And perhaps it’s qualitatively (not only literally) scrunched in the middle of those from the Côte de Beaune, under Volnay, Pommard and even slightly lower on the hierarchy than Savignly-les Beaune, which I attribute mostly to the quality of domaines that achieve in the latter, like Bize, Pavelot and other big names from outside the appellation who have been drawn to it, like Lalou Bize-Leroy, Bruno Clair and Mongeard Mugneret.

Corton, the quiet brute in the family of red grand crus, is experiencing a makeover and resurgence of interest. It seems to be the best value—if you can say such a thing—red grand cru appellation at the moment in the Côte d’Or, if not matched in price by what some consider lesser grand crus like Echezeaux and Clos Vougeots (at least from many producers), for example. Perhaps the new property taken by Domaine de la Romanée-Conti has piqued interest in Corton along with the increased scarcity and absurdly elevated prices of other red grand crus made by a load of fabulous, small production, big-name producers. Corton’s Pinot Noir vineyards seem to be the last of the great hills to be tamed in the modern era, and while its natural attributes may always be more brute than beauty compared to most other Grand Crus, there are those, like David, who are illuminating its finer points.

We begin with the Beaune Village, where the plantings range from circa 1957 to 1983 within four parcels. 20% whole clusters are typical and will vary every year. Most of the wines go through the same kind of processing with two pumpovers at the beginning of its natural fermentation and four punchdowns in total toward the end. The fermentation for this wine was short compared to most of the rest of the range with around twelve to fourteen days. It spent twelve months or so in oak before being bottled. My experience with this wine has been that it is an exceptional village wine and I imagine it’s incomparable in its high quality to almost all other Beaune village wines.

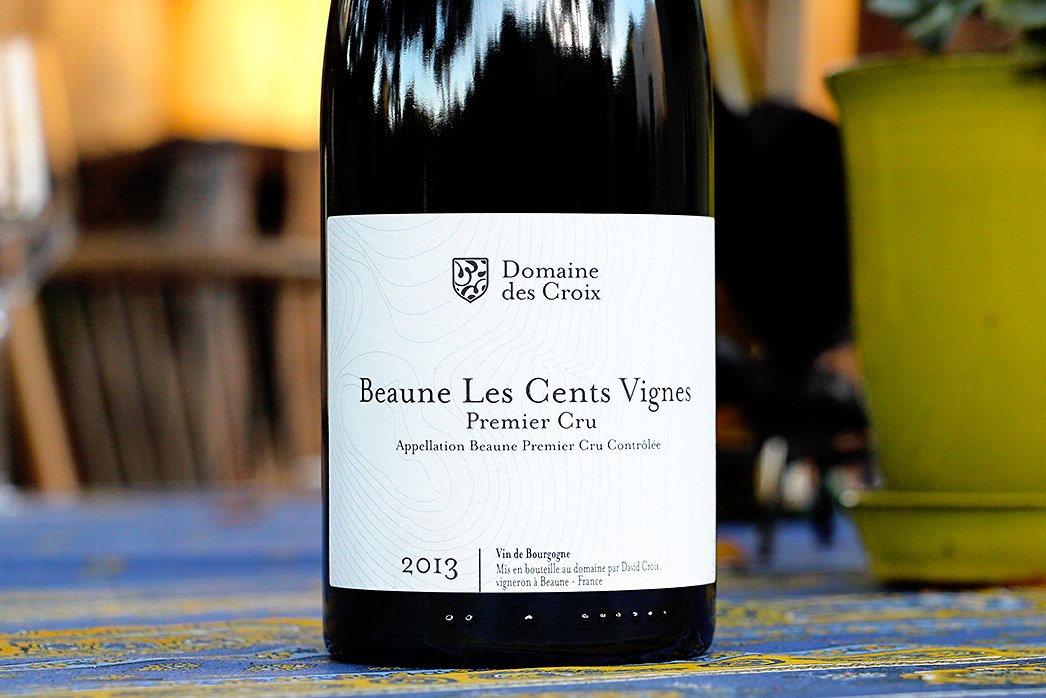

Croix’s Beaune 1er Cru Les Cents Vignes is the best of his Beaune premier crus to drink young. David teases it for its early availability, suggesting a lack of profundity, but we don’t see it like that. There’s only beauty here. It’s the playful one in the range of premier crus—full of pleasure and no pretension. It sits low on the slope with brown gravelly-clay soil with grèze litée in the upper section and with alluvial soils in the bottom. Grèze litée is an interesting formation in certain spots on the Côte. It’s a small grain rock with sharp angles and often kind of rectangular or square, and about the size of our teeth. It’s a physical component that affects drainage in a positive way, at least when there is rain. In 2017 he used 15% stems and the fermentation lasted around thirteen or fourteen days, followed by aging for thirteen months in oak before bottling.

The Beaune 1er Cru Bressandes is situated very close to Savigny-les-Beaune and is high up on the slope. For this reason there are usually no stems employed, because with the high rock content David—like many vignerons his age—feels that they’d contrast the built in textures already present; in this case, the “strong chalky character” David says that this vineyard consistently imparts to the wine. Bressandes is a pleasure for those who seek out great lines, solid mineral textures, lift and cut. This wine comes from vineyards planted between 1983 and 1991, and is usually fermented for eighteen days, and spends a year and a half in barrel before bottling.

Further down slope from Bressandes and above Les Cents Vignes, still on the north side of the commune, sits the Beaune 1er Cru Les Grèves directly on the mid-slope; yes, the sweet spot, as they say, where the most balanced vineyards in the Côte d’Or sit. And it’s for this reason that it’s perhaps the MVP of Croix’s Beaune lineup. That doesn’t mean that it’s always the de facto frontrunner in the bunch, but it’s likely never far from whatever we may choose as our favorite in the Croix lineup—if it’s not the favorite to begin with. The vines were planted in 1968 in soil made of a mix of brown clay and, you guessed it: grèze is in the house. As already mentioned, grèze litée provides good drainage to balance out the clay’s capacity to be stingy with water—making for a fabulous soil balance that translates to the wine, endowing it with fine but solid textures and a good balance of vertical (mineral, tension) and horizontal (richness and flavor) elements. There are normally 20-25% stems used here, the fermentation lasted around thirteen days and the wine ages for about thirteen months in wood before bottling.

Normally one of the wines that may pique the height of one’s curiosity in David’s range is his Beaune 1er Cru Pertuisots. The others are somehow predictable, but in the best comforting and reassuring sort of way. This wine always carries some x-factors that are quite difficult to put your finger on… We’re on the south side of Beaune now, close to Pommard, with vines planted in 1971 and 1987 on deep clay soils and limestone bedrock. Perhaps its enigmatic quality is imparted through its cool, mineral texture and the wild berry and fresh savory green herb characteristics—that Pommard-like grit and untamed quality, one all too often these days under-appreciated by newer Burgundy drinkers. It’s got 20-25% stems included for its seventeen or eighteen days of fermentation, followed by a year and a half in wood before bottling.

(The hill of Corton is pictured above)

With Croix’s two red grand crus the differences begin with their terroirs. The Grand Cru Corton Les Grèves is ideally situated on the eastern slope about midway up, with a good balance of brown clay mixed with limestone rocks and chailles—a sort of flint stone (or in English, a chert; in French a silex)—atop hard limestone bedrock. The Grand Cru Corton La Vigne au Saint is low down on the slope facing south with deeper clay topsoil. Les Grèves gets no stems, La Vigne au Saint gets 50%. (If you haven’t noticed yet, there is a correlation between some cellars where in stonier soils there is less stem used, and with more clay heavy soils there is more stem.) Les Grèves was a 20-day ferment and La Vigne au Saint sixteen days. Both were nineteen months in barrel before bottling in 2017, and in 2018 they will both be bottled after twenty-two months. Perhaps one could speculate that La Vigne au Saint is more upfront, while Grèves takes a little bit of time to perform once the corks are pulled. However, these contrasts vary from year to year and sometimes they are the exact opposite of what’s expected.

David regularly laments his parcels of Corton as somehow being the lesser of the hill within the grand cru lieux-dits because they are often not considered to be in the same qualitative level as the Clos du Roi, the king of this grand cru’s lieux-dits on the hill. But we don’t buy it. A young and idealistic winegrower from Champagne we recently began to work with, Maxime Ponson, said that he believes that in many cases vineyards that take less work to achieve a great result doesn’t mean those that require more work to achieve a similarly great result are lesser vineyards; it’s a matter of effort and understanding what to do to make the best wine you can with each parcel. David does a fine job with his grand crus and they easily rise to the expectation we may have for grand cru wines. Fortunately, they are still priced fairly (for those who can afford to play the in the financially slippery slope of Burgundy) and I would expect that given this vintage, these wines will be a knockout and deliver on the expectations from those looking for a true grand cru experience from a young wine.

David Croix’s Corton-Charlemagne parcel is located in Le Charlemagne, an interior subdivision lieu-dit of this grand cru and part of the commune, Aloxe-Corton. His vineyard is just below the forest that caps this three-sided hill, and faces west at an altitude of 320 to 330 meters. The bedrock here is pernand marl, a white calcareous marlstone with a high silt content, giving the rock a grittier texture to the touch than other usual marls within the Côte d’Or. The topsoil is composed of material derived from the bedrock as well as clay and limestone scree from the top of the hill. The parcel’s Chardonnay vines were completely replanted in the mid- and late-1980s.

The upper section of Le Charlemagne’s white marls and their higher than average silt content seem to impart “a lot of texture with salinity and tannin to the wines—delicate tannins, sensitive to too much new oak,” David explained. In the most recent vintages he’s moved away from aging in newer wood to allow these finely textured grape tannins to not be covered by stronger and potentially harsher wood tannins from newer oak barrels. He now uses 350-liter barrels with a smaller proportion of new wood, which he views as a good compromise. The 228 and 500-liter French oak barrels found throughout his cellar he views as less ideal given how “dense” this wine is. He believes his Corton-Charlemagne needs longer-term soft massaging through the right amount of aeration without taking on new oak notes to achieve his ideal wine. The longer aging time in the 350-liter barrels builds on the wine’s freshness, its naturally strong core power and intricate complexity. This Corton-Charlemagne is notably more bright and elegant than ever.