I woke at seven thirty and had finished demolishing a fresh pile of baguettes by eight, when we hit the road. Our destination for the day was Domaine du Pas de L’Escalette, in the Languedoc, a major wine producing region in the south of France that stretches from Provence up to the Pyrenees Mountains, with Spain along one border. Many of the predominant varietals there, such as Grenache, can yield a lot of fruit elsewhere, but in the cool weather where Pas de L’Escalette is located the yields are low and the wines more fresh and high-toned. The Languedoc actually produces a huge proportion of French wine, but since a lot of them are high octane, it’s not a largely desirable source for some segments of the US market, where low alcohol is the current trend.

Ted had met Julien Zernott and his wife, Delphine Rousseau, of Domaine du Pas de L’Escalette, a few weeks earlier, an event that left him wanting to give the wines another taste. Nicolas Rossignol made the introduction when they all happened to visit his cellar in Burgundy at the same time. Ted hesitated to further the conversation with Julien after an invitation to the domaine because they were already represented in the states and he didn’t want to step on the other importers’ toes. But when as they departed, Zernott gave Ted a couple bottles and they agreed to talk.

Ted had been asking himself, “Am I doing the right thing?,” but after wrestling with the possibility of working with Zernott a little longer, he decided, “why not?” He would go into the meeting with no expectations and simply view it as an opportunity to learn more and meet up with an interesting vigneron who had given him a great first impression.

We passed through the Camargue river delta, a marshy land where the Rhône River meets the Mediterranean Sea. Camargue Horses, one of the oldest breeds in the world, are indigenous to the area, and a lot of sea salt is harvested there as well. The vineyards around us were flat and thin and Ted remarked that they generally produce cheap and unremarkable table wine.

There were many Roman ruins along the road, the remnants of walls and structures from that fallen empire. I was yet again struck by these remnants of ancient history scattered all over France and how the majority of it was vandalized with colorful graffiti. Little red and yellow flowers danced in the Mistral along the shoulder as we passed, and the sky was a shock of dark blue, the thin white clouds distant smudges on the horizon. Though it’s tucked away a little inland from the coast, the Languedoc has long been thought by many to be to underrated in its beauty, and it’s free of the tourists that flock to better-known destinations.

Further to the north and west we entered the Costières de Nîmes AOC, a huge area also known for inexpensive wines, usually blends led by Grenache and somewhat similar in style to other appellations in the Southern Rhône Valley. Ted works with a domaine from the appellation, Terre des Chardons, and thinks other wines in the AOC would be better if people would make just a few changes, such as adopting organic and biodynamic standards similar to what Terre des Chardons uses. Another producer he used to import from further north in the Languedoc uses natural techniques and sometimes their wines are really solid, while others (as with many natural producers who are more at the mercy of nature), not so much.

We bent south around the sea toward Montpellier, where beige, orange and yellow stucco buildings with terra cotta tiled roofs spread out from each side of a highway lined with dense stands of trees. The city was heavily bombed in WWII so most of the structures are more modern than in many other places we had visited, and there was lush greenery and graffiti crawling across every wall on the underpasses.

The road turned north and inland again through rolling hills with huge white limestone boulders scattered among the scrub, a landscape similar to that around the 118 between LA and Ventura. We passed the town of Mas Lavayre, situated in an area chock-full of uranium ore, and continued toward the ancient commune of Lodève, which dates back to the Gauls and where the hills are all red with iron rich soils. We were getting into a new territory for Ted, geographically and geologically, and he was clearly excited.

“What’s getting interesting here is that we’re living in an era where the greatest producers in Burgundy, Champagne, the Loire, Germany, Austria, etc, are all in a window to make incredible wines in the increasing heat; they used to have a good season every few years and now five out of six are good or great, but that’s about to change. Right now, it’s much better for consistency in these colder areas, yet as the heat continues to rise, they’ll start to get inconsistent again because of heat instead of the old problem of the cold.” It was strange to think that there could be areas of the world that might actually be benefiting from climate change—the perfect ammunition for deniers. But most of us know that it’s a serious problem, and the beneficiaries won’t be such for long.

The navigation system kept giving us poor directions, and after taking a few wrong turns on some narrow side roads, we finally found our way to the driveway of Domaine du Pas de L’Escalette.

The winery building is a striking piece of modernism with a limestone tile façade, plain but for three four-by-fifteen-foot glass slots, the center one with a door at the bottom. The structure’s shape, with one rectangle and two symmetrical windowless wings on each side, gives it the appearance of a temple from another world.

The delays had us running late, and Julien Zernott was already waiting in the parking lot with his father-in-law and a young couple who were also related in some way that I missed, and who didn’t speak English. Julien is at least six four, and built like a linebacker (another ex-rugby player like Jean-Claude Masson back in the Savoie), with broad shoulders and the belly of a man who likes the finer things. He has cherubic cheeks that pinch his small eyes almost closed when he smiles his gape-toothed smile, which he does constantly. He shook my hand and almost crushed it in his bear paw, introduced his family, then gestured for everyone to jump into his old and dusty SUV.

We tore off down a narrow road through some of the most beautiful scenery we had seen yet. The vineyards rolled across wavy land in a long valley between steep hills of the deepest green, with jagged sandstone pinnacles stabbing upward from the ridges all around. The sky was spotless and rich blue, and a cool breeze kept the air under the bright sun mild and dreamy.

The space between the vines was pure limestone scree, with thin grasses and weeds poking through on Julien’s parcels. Some of the sections belonging to other makers were bare of green—clear signs of the herbicide that he shuns. The limestone was scattered in every direction, from the tiniest pebble to the billiard ball rocks to the brick and cinderblock-sized pieces used to build the walls winding all over the land. Some were four feet tall, and some were eight, and every stone was stacked and locked together with puzzle-like precision, with no mortar in sight. Julien said that they were built partially to block the wind, but mainly they were just a way to clean up all the extra stones without just piling them into unsightly mounds.

In the middle of some of the walls there were little stone huts called Bergers, also built without mortar; they look like igloos constructed with carefully stacked rocks instead of ice blocks. Inside, there were large stones to sit on around a fire pit in the center under a ventilation hole in a ceiling propped up by wooden beams. Apparently these were used by shepherds who worked the sheep in these hills in a distant past, before they were vineyards. And in the decades since, they’ve been used to warm the fieldworkers on the coldest days. In any case, there was no way I could look at a stone hut and not think, “Middle Ages,” and maybe even, “Bring out your dead!”

When Ted inevitably brought up the extremely rocky soil under our feet, Julien said that it was remarkably easy for the vines to get down into it, to squeeze through the tiny spaces in the scree. Julien pointed at a few hectares of vines that he had planted in 2003 and said they were yellow because of a recent cold snap; he has planted twenty hectares of different varietals since 2013. He then nodded at more of his parcels nearby, some sixty-year-old Grenache and eighty-year-old Carignan.

Andrea took photos of the landscape from every angle, and I would bet that they were almost all keepers. She and Ted got shots of Julien as he spoke, and he was camera friendly, smiling and allowing for countless candid action shots as he made gestures all around.

Ted noted that all the biodiversity of grasses coming up between the rows made it clear that they were employing organic and biodynamic techniques, Ted’s ideal conditions for healthy fruit. “But we live with the animals,” Julien added. “Small deer and boar eat the grapes. People hunt but don’t kill them all, so there will always be more. The grapes are always in danger.” As with every vigneron we had met so far, Zernott is always walking a fine line to preserve his crop, in one way or another.

He took us over to a corner of his property that comes to a point at the top of a hill where two of the tallest stone walls meet. I turned around and was struck by a stunning view of the entire valley that opened out from where we stood in the tip of a giant, inverted V. There were countless patches of different greens of grass and vines, and the mix of deciduous and pine trees growing from the scattered pastures below the towering crenulated hillsides that cradled the valley around us.

There were two square sitting blocks arranged around a cocktail table fashioned from one long stone. He showed us a small branch protruding from a nearby tree. It looked different from the others around it and was braced to a limb with some sort of tape; though it was grafted to a wild plum tree, in a few months it would produce cherries to snack on.

He walked over to one of the walls and pushed on the edge of a big block, which was really just a thin stone façade, actually a small door that swung open on a hinge that revealed a hidden cubbyhole behind it. He reached inside and pulled out a bottle of rosé and a clutch of glasses. We all gathered around the stone table and tasted the crisp and refreshing wine, still cold from its chilly stone storage, despite the bright sun and warmth of the day. It was the perfect accompaniment to the herbal breeze.

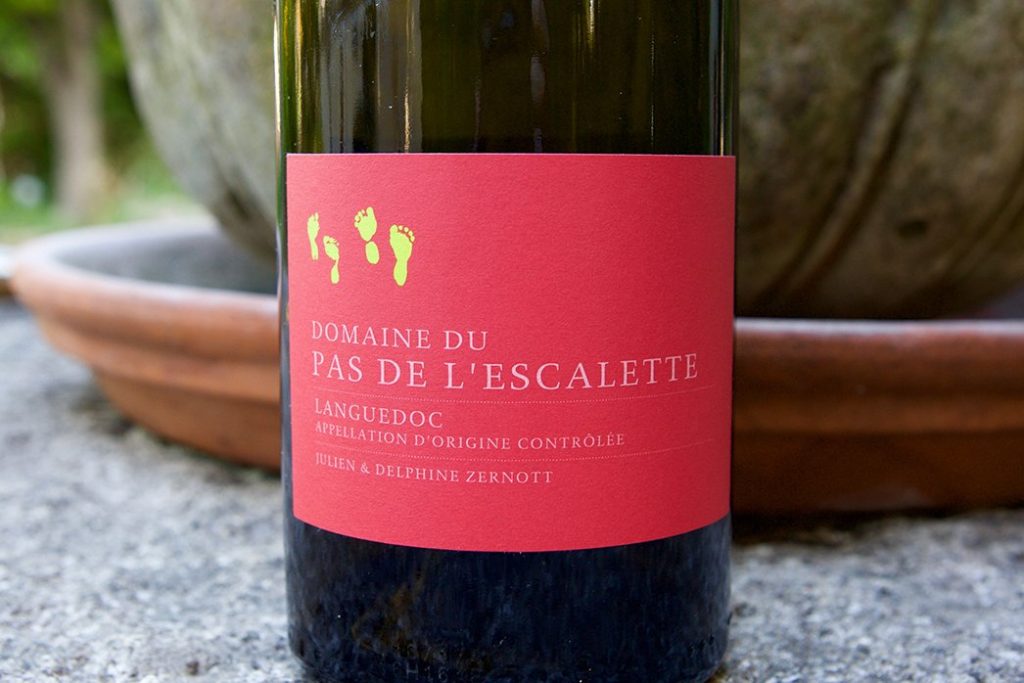

We returned to the winery and were greeted by Julien’s wife, Delphine. She smiled warmly and shook our hands from behind a sleek modern marble bar in a tasting room with cork-tiled walls. Julien told us that she runs the business side of things, raising his palms in a playful, “I have no idea what that entails,” manner. She also created all of the labels for the wines, which Ted immediately complimented for their simplicity. One series that I found particularly charming had tiny recreations of their children’s footprints walking up the side of the bottle.

As she poured tastes, including a beautiful blend of mostly Grenache with some Carignan and Syrah, followed by their Syrah dominant blend, Julien said, “you need to learn enology so you can forget it. It’s important to just observe the wines. It’s fine to know how yeast works, but we don’t add commercial yeast to anything but the rosé, where it’s necessary. Everything else is naturally occurring yeast. You have to work with your heart and not with your head. We honor the terroir. We look for the holy grail.”

Ted nodded vigorously with a big smile on his face. What Julien might not have known was that it could have been Ted himself who had spoken these words, verbatim, all the way down to the “holy grail” comment—one of his favorites. It was no wonder that they had hit it off back in Rossignol’s cellar; this guy was totally speaking Ted’s language. Then Julien said, “I prefer elegant wines over power,” to which Ted responded with a wry grin, “I do, too. I prefer a woman in my glass, not a man.” It took a quick moment for the words to sink in, but once they did, Julien released a loud chuckle and nodded in kind.

Julien led us through a tall sliding door to a big room lined with relatively new, wooden Stockinger barrels, then through another door where there were some older barrels and his steel tanks. We tasted a few of his aging wines from his pipette as he and Ted broached the subject of import. After this visit, Ted was all in, and Julien sounded interested as well. They agreed on pallet allotments for the coming vintages and that was that: they were in business.

We were out of time and needed to get on the road again. When we asked Delphine where we might pick up a sandwich, she quickly said she’d make us one herself and invited us up to the house, a low slung annex to the winery that seemed certain to have been designed and built by the same people. The glass front was almost entirely open to the view of the valley, and eight or so friends and family sat around a long table on a covered patio, playing cards. They smiled and waved and beckoned us to join them and asked us where in the states we were from. It was a beautiful picture of the incredible life that Julien and Delphine have crafted for themselves.

Inside, a teenage girl offered me some almond brittle from the oven, which I gladly took and instantly devoured, then silently wished for more the second it was gone. Delphine cut into a big loaf of rustic bread, spread gobs of fresh butter on the slices, grabbed from a thick stack of jambon de Bayon and pieces from a wheel of local cheese and piled it all together. She gave us each big hugs and sent us on our way.

A quarter mile down the road, I tore into the sandwich, which was, of course, glorious (Hallelujah! Another ham and butter!) and I had finished mine before Ted even unwrapped his. He would remark—not for the first time, or the last—that I eat way too quickly. I don’t know why he kept harping on it; he knows I was raised by wolves.