As the meeting with the Chardigny brothers came to an end, Ted and Andrea were talking softly about needing to get back on the road for the hundred and fifty mile ride to Chablis. After some quick goodbyes, Ted was again at the mercy of the white wagon’s fickle navigation system, so we got lost in a maze of tight roads on the way out of Beaujolais while he looked around the car for a hammer to smash the dashboard screen. When we finally broke free into the countryside, we passed through Beaune again on our left and Ted pointed out Savigny-lès-Beaune on our right, an underrated AOC with great pricing (for Burgundy).

“Savigny-lès-Beaune producers don’t get the respect they deserve compared to other appellations in Burgundy; the region is extremely diverse, so I think it confuses some people. There are a lot of different aspects, that is, the way the slopes face—in many direction. The two main hills are completely different, one is north to east and the other east to direct south.” These features lead to wines with widely varying attributes, so it’s hard to define them with an easily accessible label, which is unfortunately what most consumers need.

Flying down the Autoroute du Soleil, the sky opened wide over rolling hills filled with beige cows on bright green grasses in every direction. We were in a rich dairy land, the home of Époisses, a very soft, gooey cheese with a washed rind that I love. As we got closer to Chablis, the temperature dropped to seven degrees Celsius, down from twenty-eight back in Provence (or eighty-two to forty-four, Fahrenheit.)

On entering the tiny medieval town of Chablis, we passed the Saint Pierre church, a simple Gothic structure surrounded by a crumbling graveyard and dated to the twelfth century. It’s just one of many ancient churches in the town and surrounding areas, and though I’m not religious, these buildings always hold a certain fascination for me. Probably because all of the money and architectural efforts throughout the ages went into them instead of the peasants’ mouths, which of course makes me feel more than a little conflicted on the topic and sure that they’re all haunted.

Little storefronts for boulangeries and cafés along the main drag look like they haven’t changed for hundreds of years. Then you see slick, modern glass-front wine shops here and there, jarring in their shiny newness. We were running a little late and finding a spot on the street took longer than anticipated, and when we stepped out of the car, the air was a shock of freezing cold in the gray-blue dusk.

The restaurant for the night was a new place called Les Trois Bourgeons, run by the same group who owns the famous Au Fil du Zinc, a few blocks away. It being a Tuesday, Zinc was closed, so Bourgeons picked up the slack. Our table wasn’t ready, which was fine, because our dinner companions were even later than we were.

Then the notorious Romain Collet finally made an appearance. Another vigneron Ted frequently refers to as one of his favorite guys in France, Collet is the son of Gilles Collet, a quietly preeminent Chablis producer over the last few decades. In recent years Romain has taken the reigns from his father, and is continuing to make some of the finest wines in the region—with a little help from his family’s large holdings of Grand and Premier Cru parcels. When he’s not applying his inexhaustible energy to vinification and farming, he does the same to eating and drinking and partying—to having as much fun as possible; the stories of his all-night hijinks are legendary. But that evening he seemed tired, for reasons that he would get into later.

Romain Collet looks remarkably like a young, mustachioed Timothy Dalton from Flash Gordon, but with a Franco nose, a tangle of teeth and (at the time) a wild and wavy head of shoulder length hair. He smokes incessantly, which I thought strange for someone with such a highly-tuned pallet and sense of smell—abilities he clearly depends on for his craft, and apparently this contradiction is not uncommon in France.

At one point he said that he smokes a pack a day and his breakfast consists of just a cup of coffee and a cigarette. Of course, as a non-smoker and habitual square meal breakfast-eater, I was utterly appalled. Yet he won a national blind tasting event when he was just twenty-one, and has only gotten better at it; he can still detect the minutest differences between cuvées. It is true that he was born into his family’s business, but he is one of those rare cases where his extraordinary natural talents fit the bill perfectly.

He introduced his girlfriend Charlotte, who smiled politely, shook our hands and smoked as vigorously as he did. She worked the desk at a hotel in town at night and helped Romain with office work during the day. They were planning to buy a new house together soon, and she had every intention of quitting the hotel to work with him full time. They looked at each other, dropped their cigarettes on the ground and stomped them out in unison. Romain looked around at everyone with a wink, slapped his hands, rubbed them together and said, “Hungry?”

We took a seat at a table near the door, the only one available in the room with just nine others. I was closest to the entrance, and every time someone came in, they brought the quickly plummeting temperatures in with them. I kept my jacket on the entire meal and pined for the thicker coat I had left in the car.

The décor was simple, contemporary and unremarkable, with cold, bright overhead LED lighting. But Romain said the place was getting some buzz and he’d been looking forward to checking it out. He deferred control of the wine list to Ted, who ordered two wines that he imports and a champagne that he wished he could add to his book. He picked up a glass from the table, took a sniff, and immediately said they needed a rinse. He does this at every meal, but this was the first of the trip to fail the test. Usually it’s the smell of wet dog that comes with old water or a dirty drying rag, but this was a case of the opposite: too much sanitizer in the wash.

The server came to pour and I was surprised when he didn’t mention the glasses; he always has them replaced when they come flawed. It occurred to me that he was making an effort to curb his fastidiousness in this new place with this old friend. Instead, he nodded over at a tall man with gray hair a couple tables away and said, “that guy ran a tasting at a restaurant where I worked in Arizona, twenty years ago. Small world.” I thought, yeah, small world—and you have a hell of a memory.

As the door opened and closed again behind me, chilling me every time, Romain talked about being up all night the night before in an effort to save his crops, the reason for his apparent fatigue. The unseasonable cold was posing a real threat; if the thermometer dropped below negative two degrees Celsius, frost would form and destroy the new buds that were just starting to appear. So the producers in the area resort to extreme measures: teams of workers lay out hundreds of cans of fuel (like big cans of Sterno) between the rows of vines, which they light if the temperature falls to that dreaded number.

Romain pulled out his phone and showed us a video a friend had posted on Facebook the night before, footage of darkened hillsides alight with orange blossoms of thickly smoking flames as far as the eye could see. It was a stunning sight, made horrific by what it meant for this to be happening, the difference between making wine the coming season, or not. As with what happened to Dutraive after the hail in 2016, vignerons can buy grapes from other growers to produce something, but resulting wines are just usually not the same.

In the case of guys like Collet, it is not an easy thing to replace fruit from Grand and Premier Cru vineyards. He has lesser valued parcels, but of course it is these top plots that get first priority when the threat of frost looms. He had so far dodged the bullet, but he would be watching the temperature carefully on a phone app as dinner stretched later into the night. His guys were already out in the fields making preparations, and he would join them again if and when the time came.

The stress of these times turned the talk to the gambles producers make every year, the careful balancing act of keeping a company afloat. He finds that the hardest part is deciding whether to bottle all the wine once it’s finished, or sell a good portion off to negociants (who will bottle it under their own label) to make ends meet, but at the cost of losing distribution of his own product. Vignerons will have to do this in lean years, if the financial standing of the winery is shaky.

Families sometimes need to make the quick sale to negociants even in solid years, to help them prepare for the disastrous ones. Just a few bad seasons in a row without proper preparation can burn up financial reserves and break their business. Talk like this really reminded me that we weren’t in Bordeaux, where wineries are owned by endless supplies of old money and new corporate backing. People like the Collet’s are artisans who live at the mercy of nature like any Midwestern farmer.

I was hungry. Though the starter list included what I was informed was a local favorite, “oeuf en meurette,” I ordered the sautéed trout “Prégilbert,” to be followed by the roasted pork loin with creamy mushroom polenta. The trout was tender and delicately spiced, dotted with orange trout eggs, a little too like the salmon eggs I used to catch fish when I was a kid. The pork was good, and with the polenta, just like something I could have ordered at any number $$$ Yelp restaurants in the States. I also realized that my tepid impressions were probably being cooled by the freezing wind at my back.

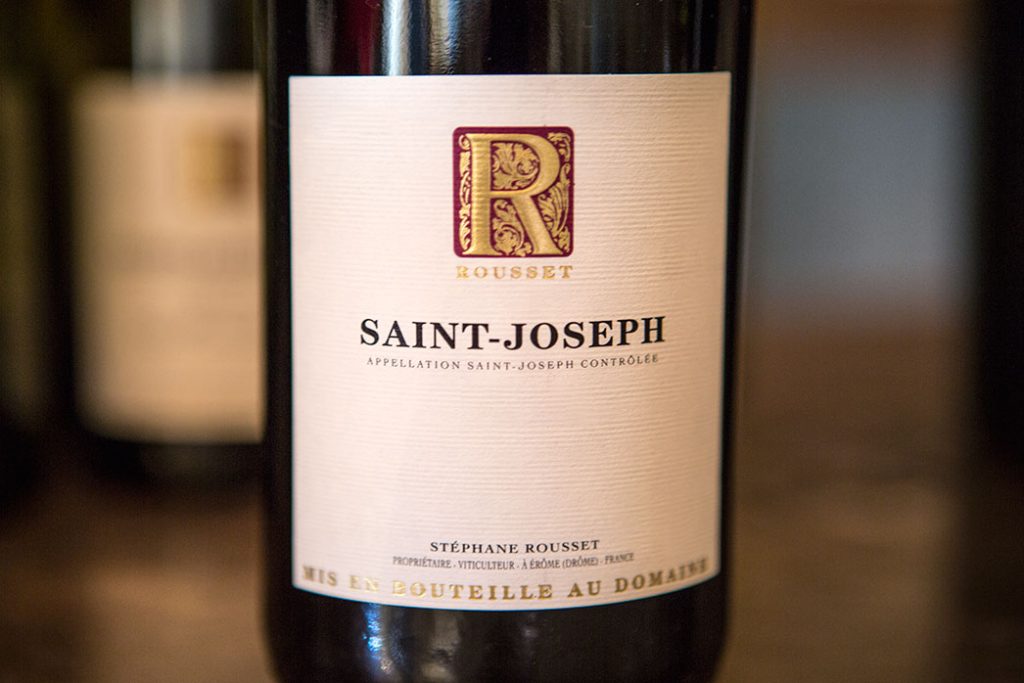

The 2013 Rousset St. Joseph, on the other hand, was delicious. I drank less than my fair share, but a little went a long way. Ted recently started carrying the label after pursuing them for quite a few years and kept raving about it.

The server was a cheerful Japanese émigrée whom Ted had also as a server over at Au Fils du Zinc in recent months. The two cooks in the open kitchen were Japanese as well, and Ted went on to say that there’s a decent Japanese population in France. Apparently a lot of the chefs at Au Fills are also Japanese.

Romain started in on a story about a good friend from Tel Aviv, a professional soccer player who drank very little and was a very careful eater at home, but when he came to France, all bets were off. He ate and drank all day and night and was a comrade-in-arms during many a forty-eight-hour fête. Since I was still feeling under the weather and taking judicious sips, and had passed on ordering desert, I didn’t think I was imagining it when I caught Romain giving me the suspicious side-eye during the story. I might have been just trying to ward off his appraising gaze when Ted’s chocolate crème brûlée came and I stole three quick bites that garnered a glare and growl from its owner.

The dinner wrapped up pretty quickly, but we knew we’d see Romain a few times more in the coming days. We all stood shivering on the street by the white wagon as Romain waited for the temperature to update on his phone; he still didn’t know if he’d need to man the fires again. A big digital sign in the town square right above where we were standing read zero degrees Celsius. It didn’t look good.

Ted took us onto a dark country road outside of town to the neighboring village of Préhy, a tiny cluster of ancient cottages, population 129. We entered the main street and blew right by our Airbnb in the very first building, the front of which had been converted into the only modern glass facade around. It was late and freezing and it had been a very long day, but I paused in the middle of the street to notice the black sky packed with stars, the local light pollution nil. Then we stumbled into the two story apartment full of Ikea furniture, and tromped up a rickety metal spiral staircase that seemed to be made from a kit, like all the other stuff. Ted mentioned that the building was owned by the daughter of a famous biodynamic producer in the area.

The three of us were to share the one big bedroom with an accordion door and an exposed bathroom sink and shower, while their friends Geraldine and Arnaud Lambert, who were joining us the next day, would take the other one for themselves. But the place was much smaller than advertised. By this time, my loud snoring had become a bit of a joke, and with the prospect of sharing a room with me, it suddenly wasn’t funny to Andrea anymore.

Everyone was tired and tensions ran high for a few minutes, until Ted came up with the idea to book another place in town for his friends. I was left in the big room, where I had already settled, and was relieved that I wouldn’t be sharing it. I felt both guilty and grateful that my sleep difficulties had afforded me some much needed solitude.