“Please send me some good news, buddy!” This was our Barbaresco producer Dave Fletcher’s response to a market update email sent to our growers, one that outlined some potential pitfalls we might experience in 2025. In the face of recent surreal events, the concept of “good news” feels almost detached from reality, even though we all know there’s always something to look forward to on the horizon.

In mid-January, I sent out an inventory of the damage already done and a look ahead for 2025. The report was, as they say, realistic. As often happens, hard truths land differently for each of us. For those with experience and a family war chest built and tucked away over generations, the ebbs and flows of business are an old song and expected to come around now and again. But for us relative newcomers, idealists, and those still bound by the ink on the fifty we-own-you-now bank documents, the weight of it all can be enormous.

We all had a load on our minds, including the East Coast and Gulf port strikes planned for January 15th that were thankfully pushed off for six years. The only remaining specter seemed to be the ominous import tariffs proposed by the world’s most famous narcissistic terrorist—a generational talent in his own right. Apparently, for some, our new ruler’s stance represents all of us Americans, as one of our French growers pulled our US allocation because that guy was reelected—which is as dumb as Freedom Fries. These two potential events incited a mad importer dash to bring in as much product from all business sectors as possible in the short term, resulting in another supply chain log jam of post-pandemic proportions. (Like we needed that.) But we here at The Source did it too. What importers couldn’t? We’re damned if we do, replaced if we don’t—or something like that. But while we endeavored to engage these challenges, nothing could prepare Angelinos for the unimaginable speed and scale of the fires that descended on their city.

Of every possible outcome of January 2025, nothing hits home like an unstoppably fast tsunami of fire. On January 6th one of the world’s great cities ignited and burned like hell; unlike all the other fires before that burned mostly forest, this one included an unprecedented quantity of structures. There are few more humbling moments than if your house burns down. Or those of your friends and neighbors.

Someone with whom we’re close in the Los Angeles wine community has lost everything: Mike Ulanday, a longtime supporter and one of the most gracious people we’ve had the privilege of working with, escaped with nothing more than his wife, three kids and three dogs. While it’s easy to be generous with kind words, they don’t rebuild homes. If you’re able to help, please consider supporting the Ulanday family through their Givesendgo.com link. They’re by no means the only ones affected, but we don’t yet have names of others in the mega-loss department. Please let us know anyone else you might know who is, and we’ll add their information to our next newsletter.

SANTA BARBARA

Tuesday, March 4th

The Factory, 616 E Haley St, Santa Barbara, CA 93103

SAN FRANCISCO

Wednesday, March 5th

La Connessa, 1695 Mariposa St, San Francisco, CA 94107

SAN DIEGO

Monday, March 10th

Vino Carta, 2161 India St, San Diego, CA 92101

LOS ANGELES

Tuesday, March 11th

The Wine House, 2311 Cotner Ave, Los Angeles, CA 9006

Please contact your salesperson to reserve a time. The tasting will take approximately one hour.

We normally feature a series of newly arrived goods each month in our newsletter, but due to extensive delays in ocean freight and the California fires, we’ll hold off until March, when we’ll have wines from all our European countries.

Coming off the 2023 film industry strikes and what we knew would be a long recovery, 2024 was the kind of year that wears you down. (It was my busiest travel year since 2004 when I cycled across Europe for a six-month tour of many wine lands and almost every major European city I had read and dreamed about for years.) I thought my travels would wrap up quietly at the end of September, with Denmark tacked on as a last-minute stop. By then, I had already hit all the big European wine regions where we work. However, due to my extensive summer tour in the US during the perfect time to visit wineries, I decided to push Italy and Germany into early 2025. Somehow, we still managed to squeeze in firsts like the Canary Islands and Morocco, and the latter wasn’t about wine (for once), just something different. Add in two months of wine work coast to coast to coast (including the ever-overlooked coast of Lake Michigan) and family time in California’s Sierra Nevada to Montana’s Rockies and Iowa’s cornfields. It was one for the books.

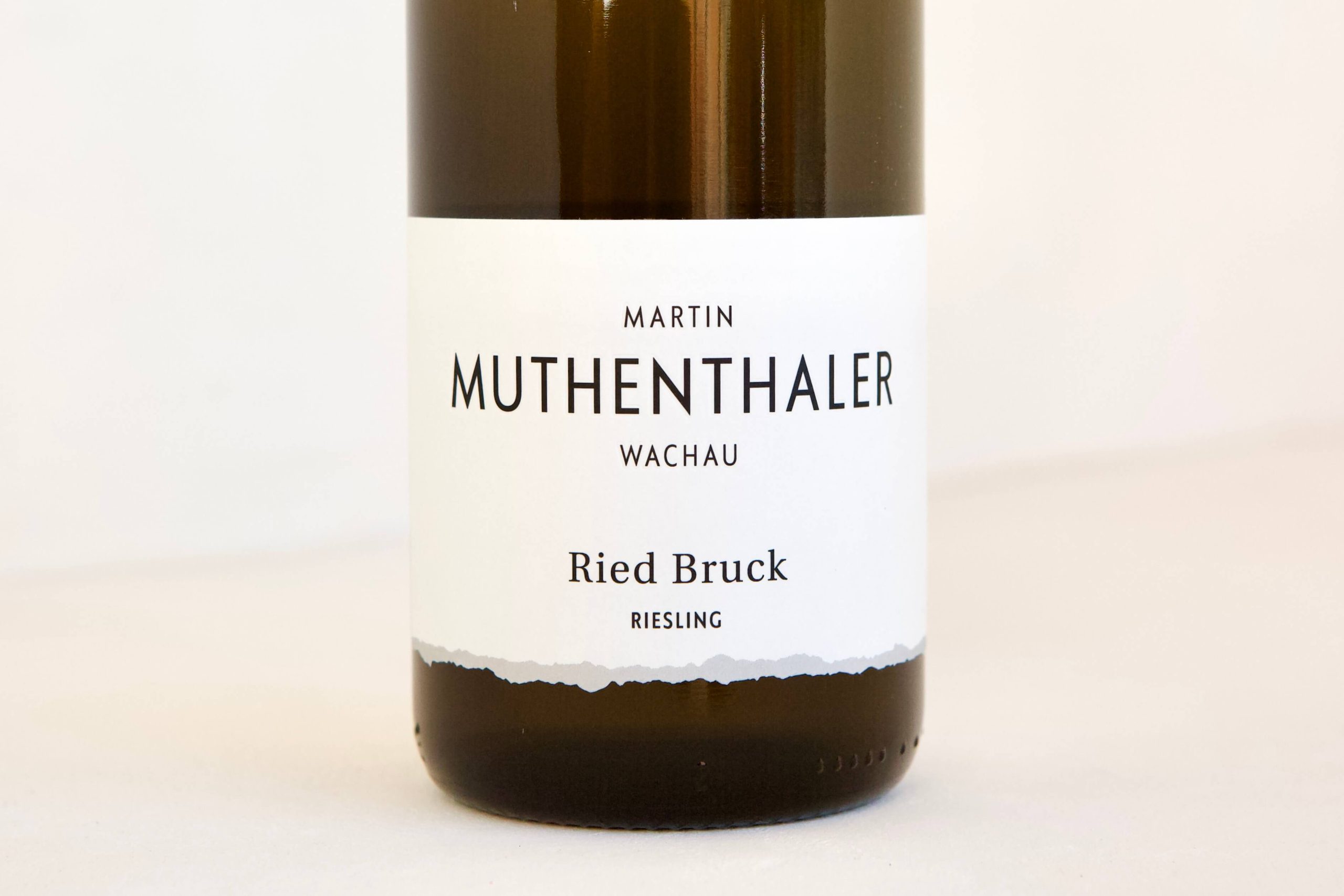

The last months of 2024 had glimmers of the high notes we hit in 2022, with the team growing stronger and some new colorful and already globally anointed feathers to add to our cap, growers at the top of their respective region’s game, with Bien de Altura (Canary Islands) and Muthenthaler (Wachau) for our national program, and Federico Graziani (Etna), and Camin Larredya (Jurançon) in California. There were others added to our national program who are not yet well known but already on their way up in the ranks: First, there’s Frédéric Haus’ Les Infiltrés Saumur wines, and Carole Kohler from Jardins de Fleury, grown on the geological transition from ancient acidic metamorphic Pangean remnants to the younger Cretaceous sandy limestones, and her Anjou wines will make their US debut in March! There was also a relatively new national grower for us from the microscopic and quietly legendary sandy Portuguese oceanside appellation of Colares, Quinta da San Miguel, which while intended for last year was pushed to this one.

I’d convinced myself that I’d catch my breath in the final quarter of the year, that I’d at least have some time to properly brace for what was shaping up to be a January for which it seemed impossible to prepare. Looming strikes and lurking tariffs, each threatening to scramble any promises and forecasts we made to growers for 2025. It was my opportunity to regroup and maybe even sleep. But greater opportunities than sleep don’t fall into your lap every day–in fact, they never do. When you see one or create one, you can’t sit back and enjoy the view, you have to take it in hand. They’re sometimes a result of your will and always in sync with the luck of timing.

While in California, I phoned a well-connected industry friend to catch up during my trip. A few days later after our dinner in his California outpost on my way to San Francisco, I reached out again when I arrived to ask if he knew anyone in New York who might be a good fit to represent us. He had a name, and one I knew well. A person I also admired, a young talent I believed shared my wanderlust and passion for wine and culture enough to get the ball rolling to start his own import or distribution company. He hadn’t quite gotten there yet, but how lucky for us! Now Remy Giannico will be our new boots on the ground in New York.

We’d settled on Remy’s start date for mid-January. While I was ready for a lengthy breather (which often takes just spending a month getting into the same bed each night), Remy had other plans. A few days after we’d agreed to make a go of it, he pitched me a changeup that could only come from someone who knows where he wants to go, someone who, when making a decision, doesn’t want to waste another minute. “What if I come to visit all the growers in November and December instead of January and February? This will help us properly launch in January. You don’t have to pay me for this time but can you cover all the expenses?”

It was a devil’s bargain against the health of my mind and body, but I couldn’t refuse an offer of his immense commitment. 2024 would no longer be remembered as just an intense travel year, it would become my year of personal odyssey—a season where I unexpectedly visited 60% of our growers twice, racking up over 150 domaine visits in total. And when I visit our growers, it’s not in areas with the grower density of Burgundy, where you can cram two or three tastings in before lunch and the same or so after because all you’re doing is tasting in the cellar. Each visit on my route is, no matter how many times I’ve seen it, often a full vineyard and cellar tour, extensive tastings out of vat and bottle, a lunch together or a late night of great wine and conversation, and always an early rise.

The trip with Remy was the most exhausting forty days of wine travel in my life. He was turning thirty-three on the road and I was a year and a half away from fifty. I was already feeling fatigued by the year, and this trip would test the consumption limits of this organism in which my consciousness was trapped. To make things even more challenging, on our so-called “days off,” I set up fifteen to thirty wines at various stops to prep Remy for the coming visits—because he’d tasted so few of our wines destined for New York before signing on. To leap from a secure living at a strong company in New York into the relatively unknown of The Source? It was indeed a humbling vote of confidence for us.

Forty days of visits and tastings through six countries, five flights and nearly 15,000 miles of windshield time on highways that stretch out like endless ribbons and others that tightly slalom from side to side on steep grades, once the conversations are temporarily exhausted (which was rare between us) there were as a lot of podcasts, and Speechify, a dangerously productive new toy to listen to anything and everything with eyes fixed on the road in front of us. I already knew Remy mostly had his Spanish down, thanks to nearly a decade in Argentina, where he lived with his Argentine father. Once in his early twenties, he returned to his roots in Santa Barbara, fell into the restaurant grind, and—like all of us who would dare to read such a lengthy newsletter as this—caught the wine bug. But what I didn’t know was just how effortlessly fluent he was, but with a warm, melodic Gaucho-inflicted Spanish accent that was sometimes harder for me to follow. When we hit France, he unconsciously started rapping in French as if it came from a past life, and if anyone has had one of those, it’s him. In Italy? Well, his Italian came out of nowhere, like yet another secret stash he’d been hiding until we’d crossed the border from the Côte d’Azur to Liguria. In Austria, somewhere in the marrow of his bones, he found some words (surely, again, from another life), and not just ja, nein, and some numbers.

For all the driving and planning I did, it often felt like I wasn’t on my trip at all, I was on his—a passenger behind the wheel. He was on-point, all the time, except when he wasn’t nodding off in the car after putting too much energy into every waking hour. He read about and studied the growers, every day, the night before or on the morning of each visit. Speechify was often cued up on the long drives beforehand, narrating some report on the region or grower we were visiting. He’s one of those artistic lefties with a penchant for microscopic handwriting—not the smart guy you want beside you in class if you need to borrow an answer for a test. He’s great in the kitchen with cooking and cleanup, known to ride a horse like he was born in the saddle (former Polo player, and his father and brother professionals), current on every new piece of tech like a millennial savant, and damn near qualified (and motivated) with his various university studies in Geography to map the world. He shot videos on-site and edited between visits; he’s good with his camera (though not always mindful of its fragility; there were a few drops and a broken lens). He illustrates well, designs wine labels, and devours culture for breakfast. But the best of him? He’s a giver, endlessly curious, and a great travel companion. He also unexpectedly pops off like a scholar on many topics besides wine. I often thought it and occasionally even said to our growers along the way: How the hell does he know all this stuff?

When I think back to where I was at thirty-three? Well, we all have our path. Those who want to move fast are only limited by their natural pace. But when I think about where I was at thirty-three on so many of our shared interests compared to where he is now? Farm League.

What was most unnerving about our trip were the flowers. Remy flew into Porto the night before our first field day. The itinerary was tailored mostly for only growers with whom we have national exclusivity. After crossing the Minho River from Portugal’s Ponte de Lima, our first stop was Salnés, the heart of Rías Baixas Albariño, and a focal point of our Iberian roster. It was November 12th, and flowers that normally begin their bloom in the spring were blossoming. Even buds on shoots that had yet to be pruned were already burgeoning. Galicia would not be our last stop where springtime flowers stippled the countryside near the end of fall and the start of winter.

November is typically Galicia’s rainiest month. Yet unexpectedly good weather can be welcome in the right setting. Pedro Méndez wasn’t there but the week before I invited him for dinner, and he brought wines for Remy to taste on his first night of the trip before we headed north. It was an impressive start, and while Pedro’s Albariños are clearly special, his reds haunted Remy the entire trip and one of them made his top five wines of the journey. Manuel Moldes was on point, as usual. He has a new winery and a few new toys to ratchet things up even further. Xesteiriña’s soul-packed, core-dense, sulfite-free Albariño from their single plot on metamorphic rock was staggering and, as usual, in very short supply.

Our visit was too short for this ocean-seasoned, high-voltage wine territory, their generous makers, and the best fall weather I’d ever witnessed in Salnés. But we were off to Ribeiro, the spiritual and most historic wine center of Galicia, and then to Ribeira Sacra, the sacred riverbank.

Indeed, there are talented growers from Ribeiro other than ours, but I wouldn’t trade our two for any of them. As many have already experienced, Cume do Avia’s 2022s are gorgeous and without a doubt their best effort to date; the reds bring me back to my first tastes in their barrel room in early 2018 and represent my inspiration for the vines I intend to one day plant on my tiny little Portuguese terraces (Caíño Longo and Brancellao, the muses) so I can craft some wine again. I was already generously offered vine cuttings from their regional massale selections. Their low-alcohol red wines remain some of the most frequented at my table, with their glorious high tones and enviable delicacy, armored with their metamorphic and igneous bedrock and the Atlantic’s freshness. Iago’s Augaleveda wines continue to climb, and now his newly released 2022s are at the edge of outer space. This man’s an astronaut on a solo flight to Mars.

Our two main producers in Ribeira Sacra are churning out the best of their careers. First, Prádio, a name easy to pronounce, must change because of an unexpected lawsuit. Now it’s called Familia Seoane Novelle—good luck pronouncing that middle word, the family name. So many vowels! Xabi Seoane (pictured with Remy) could’ve chosen something easier for the mouth to wrap around, but he has a habit of doing things the hard way. Regardless of the phonetic challenge, and loss of the entire 2021 vintage due to mildew ravaging the area, Xabi made a jump between 2020 to 2022, almost completely redefining his style. I guess a missed vintage gives one time to reflect. Of course, he does the best he can still using organic treatments, but when he says he can’t lose it all again for the sake of ideology, I get it. 2022 was a warmer season with almost no mildew pressure, by comparison, they are the finest wines he’s produced and some of the finest in Galicia. Endowed with greater tension and purity, they’re also paler in color free of unnecessary weight, density and richness. With the finely plucked chords of his 2022s, the Cistercians who rooted both Burgundian and Galician viticulture would be proud.

Our real-life Ribeira Sacra Wolverine (well, minus the superpowers and biotechnological implants, though the attitude is fully intact), Pablo Soldavini is not only up to mischief in this land of herbicide, but he’s also up to good: whether it’s rain, shine, or fungus for days, he works all-natural viticulture all the way—at least as natural as copper and sulfur sprays can be. His wines’ high, fragrant tones are intelligent but a bit intentionally unpolished—like their maker. Pablo has more vineyards to tend to this year, but he’s a one-man show with a herniated disk, so he’s limited in how much he can take on. Though a wonderful and hospitable friend, he admits he doesn’t work well with people—so, naturally, a limited production is always to be expected. During our visit, he shared a recent disturbing development in his region’s subzone (Ribeiras do Sil, on the south side of the Sil, across from Amandi, the most famously pictured) as yet another generational round of abandonments. Vineyards are being left to the wild. I guess we’re running out of heroes for this so-called, “heroic viticulture.” So, for all aspiring natural winegrowers, it’s time to get to Ribeira Sacra! Well, it’s a cool fantasy anyway. You can buy a house for 7,000 euros and vineyards and land for a great price. But it comes with drawbacks: don’t buy before you see it. Or: best to leave it to Xabi and Pablo.

A new personal success story is quietly brewing in Ribeira Sacra, though not without some scorn and understandable skepticism from a few of our Galician growers. After nearly a year of discussions, and a handful of vineyard and winery visits at Ponte da Boga, I asked Javier Ordás de Villota, their export manager and now our friend, for a meeting with the big boss to discuss the future and a topic crucial to our ethos: true sustainability, ecological consciousness, and a word that can quickly turn conversations sour: organic. He was skeptical of our probability of pulling it off but he teed it up for me anyway.

“As importers, our role is not just to align, but to sometimes guide and give confidence when it’s needed.”

Francisco Alabart, an extremely professional and polite Catalan native, the Senior Director of Estrella Galicia’s wine and cider projects (including organic ciders), and of course, Javier’s boss, quietly listened to my pitch. I presented the idea of Ponte da Boga taking a strong position on organic farming in this region, one that’s notoriously difficult to work in this way so that they could become true industry leaders in Galician wine. Their success could have a ripple effect in the region, instilling confidence in more growers that there’s a market for their wines and that it can be successfully done on a somewhat larger scale. I also pointed out that their higher-end wines could fetch higher prices, not only because they can be called organic, but also because they’d be better wines; it’s always good to mention an increase in profits in a pitch. And just like that, he said:

“Well, we were the first major Spanish beer company to grow our own organic hops, and we have an organic cider program,” Francisco said, “so I don’t see why we can’t do this with our vineyards.”

One of the most fulfilling feelings in what we do comes out of participating in progress. While it seemed a difficult task to ask a grower working in a conventional way to consider organic farming, we walked out with a 2.5-hectare commitment from one of Ponte da Boga’s Ribeira Sacra vineyard partner’s vines. The vineyards where the experiments will take place are those of the owning family’s son, José-Maria Rivera Aguirre (Jr.), known by all as Chema. Chema already had this idea brewing and now he’s got our commitment to get behind it.

This reaction was another reassurance that as importers, our role is not just to align, but to sometimes offer guidance and boost confidence when needed. It’s obvious to me that greater ecological progress will come from encouraging growers who haven’t yet embraced less invasive methods to uncover the untapped potential in their wine through more natural processes. Changes like this thrive on openness, not an “us versus them” predisposition. And if we want to affect real change, we must walk into new places with capable and reasonable people to have an open and gentle dialogue about important things.

Born in 1991, the easygoing and extremely personable yet shy Chema explained that he’s always had a strong connection to nature and the outdoors. An avid surfer who loves the ocean, he pivoted and turned his outdoorsmanship toward the vineyards of Ponte da Boga where he interned for a couple of years starting in 2017. Since it’s always been complicated to navigate working among other members of this seventh generation of successors to the founder of Estrella Galicia, he wasn’t able to get further involved in the operations of Ponte da Boga. So, he opted to spend his time in Chantada to grow grapes on his mother’s 40 hectares of wild land, and organics was always on his mind. “I was convinced that organic viticulture was possible. And if it’s possible, it was mandatory to try,” Chema said.

It will be tough where he is, but he says that despite its much closer proximity to the Atlantic than Amandi, he doesn’t believe it has a greater mildew pressure, though that will still be his nemesis. His first go at it was three years ago with a tiny plot, but now with our interest, he’s all in on 2.5 hectares of the 16 he has planted with five more on the way. His dream? For everything to be organic, and maybe even biodynamic or regenerative farming.

Generously, the team at Ponte da Boga offered us priority for those first organic wines grown on those gorgeous terraces of shattering grayish-blue slate on the northern tip of the Chantada. As it’s the northernmost area of Ribeira Sacra, it’s subject to the Atlantic’s coldest whipping winds—exactly what the naturally low acid Mencía needs to preserve its freshness. Tasting various lots of Mencía with Ponte da Boga, the blend dominated by this vineyard was the runaway highlight.

On a high from our visit to Ponta da Boga’s new organic vineyard tour with Chema and his French native viticultural guru, Dominique Roujou de Boubee, we found our way back through Portugal with our first stop, Portugal’s most remote corner of the mainland, Trás-os-Montes.

It’s nice to see our adventurers from all over Iberia who’ve rediscovered some nearly lost terroirs and come into their own over the last five years. I’m truly proud of them. And when I think of some of those I’m most proud of, the continued perseverance of Aline at Menina D’Uva, and Arribas Wine Company’s Fred and Ricardo are simply second to none.

We didn’t approach one of Portugal’s most obscure and sparsely populated time capsules of a region with the expressed goal of planting our company’s flag like we wanted to grab credit for establishing it as the next viticultural hot spot. But when artisans make compelling wines, I don’t care where they’re from and how many of them are there, I’m gonna go after them.

What differs most between the wines of these two growers is probably the influence of their cultural heritage and university studies. Aline’s parents are Portuguese but she’s Parisian-born and raised. She has three master’s degrees (notably in Molecular Biology and Fermentation Science). She’s largely influenced by natural wines of the Loire Valley and Burgundy, and with her new life partner from Italy’s Marche, Emanuele, she’s gotten more into Italian wines now, as well. The Arribas guys are from northern Portugal and have viticulture, enology, agronomy, and biology degrees. They’ve traveled the world to work various harvests. And these two camps certainly grew up eating and drinking different things! Then there are the differences in the topography of the land they work, with Arribas being far more backbreaking with shallower and sandier soil beds in their steep igneous and metamorphic bedrock vineyards than Menina’s softer rolling hills with deeper clay and sand soils largely on metamorphic bedrock. Of course, they both deal with many varieties, with dozens more in Arribas. Aline has a new cellar, which eased the constant kinks from navigating her previous one—a virtual crawlspace built for smaller people in the Portuguese countryside. Like our other relatively new Iberian upstarts, her new releases reached her highest marks. And the guys are downright maniacs, fully committed to the Sisyphean task of something well beyond heroic viticulture.

On this trip, Fred showed us some of the steepest parcels where they carry 15-20-kilo boxes of grapes up an unterraced hills on their shoulders, spending all the diesel in their legs on what appeared to be about a hundred meters up a 50-meter vertical climb—like I said: they’re beasts. Ribeira Sacra and Douro seem more difficult and more aesthetic, but I think their work is as hard as anywhere: no carts on rails, no terraces, no stairs, nothing, just steep, either freezing or scorching hills without a spot at the bottom to load a truck and drive them up. All that labor goes into their Saroto wine—the starter kit range for by-the-glass programs! This year they beat me to the punch with their 2023 Saroto Tinto by highlighting the fruit and pleasure over the mineral and seriousness still tucked in, but further back. As I suggested he might want to develop some of these characteristics going forward, Fred set what I had just asked for right in front of us. It was like I’d ordered a wine from the replicator on the U.S.S. Enterprise! Get ready for a deliciously spry new Saroto Tinto.

We finished up in Douro with Luis Candido da Silva’s Quinta da Carolina and Vinho Verde’s Constantino Ramos before we flew to Austria. These two guys pay the same attention to detail but have completely different results. Luis’ wines are a mix of extremely progressive, tightly wound rock channelers meticulously detailed and grown on the north faces or the highest altitudes in one of the hottest and driest viticulture areas in Portugal, yet with tones so high and alcohol levels so low it’s often offensive to the local palate. Constantino’s are a nod to the history of Vinho Verde, the reds are perfectly rustic yet tame “green wines” with terse acidity and fresh wild fruits and foresty, damp, green earth notes and the full-flavored whites are grown in some of the coldest and wettest areas of Portugal, Monção e Melgaço, and the Lima Valley. This year we’ll go as far as Constantino will let us with his Loureiro Branco. As Remy says, “For its price, it’s a gift.”

I never miss flights. After a couple of static days with tons of pre-game tasting for Austria, Germany, France and Italy, we left Sant Feliu de Guíxols with plenty of time to spare. Oops, construction. Plenty of time. Divert! Wait, navigation wants to send us to the same spot! Go this way! It will surely lead us to the highway because it’s in the same direction! Right? We’re good … Wait, we need to turn around. Defeat. But we still have enough time … Thirty minutes down the road and back on track with an hour before we reach the airport, a text: “We’re starting to board.”

The text was from Manuel Moldes, our Val do Salnés luminary. It’s always fun to include some of our growers on trips to regions they’ve not been to before. He and Angel Camiña Seren, one of the long-time winemakers at Forjas del Salnés (one of the true greats of Rías Baixas), were meeting us at the Barcelona airport to join our short Austrian leg. This region was ideal to include Galicians (Forjas del Salnés is not one of our grower partners, he’s a friend) who make ripping white wines on similar acidic soil types as the Wachau, given the bedrock and soil types largely come from the same geological era, Pangea.

It took a second. Did I read the ticket wrong? My eyesight is getting worse every day. I saw a 2:40 but had clearly missed the 1 before the 2. F … Remy was on the phone in seconds with Vueling. A chance to make it or not? We don’t have bags to check! Non-committal. Finally, the agent said, “You won’t make it.” At the curb fifteen minutes before the closing gate time. Remy ran. I conceded. I had my car. There was no more time to park. “I’m in!” he texted. Sweet relief. He needed to get there in time to help these two Spaniards who didn’t speak more than a lick of English with their arrival in Vienna for the first time. Eight hours later, after taking the last flight of the day from Barcelona to Vienna—plenty of time to reflect—we were driving to Kremstal.

With an early breakfast date with Gerald and Wilma Malat, followed by a tour of Gerald’s private schnapps stash at 9 am. I left the gang for the Wachau and a quick pre-lunch visit with Martin Mittelbach from Tegernseerhof, whom they had dinner with the night before coming back to the airport to pick me up, and whom I’d already visited earlier in the year. Martin has always worked with a consciousness toward nature in his vineyards, and his conversion some years ago to organic farming was his next and most logical step. A long-time purist against allowing any amount of botrytis grapes in his Smaragds, his wines have always reflected purity and focused expressions of their terroirs. Already making world-class wines through the 2010s, the last five vintages have found new gears. To taste his 2022s next to the 2023s demonstrated how underrated 2022 is and how obviously in great form are the 2023s.

Prior to Tegernseerhof unexpectedly signing on with us in New York a few weeks before the trip, the main reason to visit Austria was for Remy to meet Martin Muthenthaler to help him better understand how this truck-driver-turned-winemaking luminary rose to the top of Austria’s wine scene. After shaking one of his thick, stained and torn, icy vice-like hands and looking at his wafer-thin frame seemingly built of steel, it’s easy to understand that work ethic is one of his cornerstones. His others are his organic farming methods, meticulous attention to detail in his vineyard work and his bond with nature’s ebbs and flows. In the cellar, his technique is simple and direct. No games. Nothing to do but shepherd each wine to a precise outcome. Along with his now world-famous neighbor and Wachau disruptor, Peter Veyder-Malberg, only a few can match the level these two are achieving and I know of none in Austria who stand above them.

After our two Spitzer Graben tastings with its two legends, we hopped on an early morning train, heading from Austria to the sunbathed, wind-whipped and freezing limestone slopes of Rheinhessen’s Grand Crus to visit mutual friends with our Austrian growers, Katharina Wechsler and her newly wedded, culinarily gifted husband, Manuel Maier. Greeting us like old friends, they cooked us up a storm of pizzas the first night, showed us their prized vines in the morning, and had a lengthy lunch prepared after the cellar tasting and served in their makeshift popup wine bar.

Every year, they up the ante, delivering classic dry Riesling from Germany’s modern-day dry Riesling hotspot, with Kirchspiel and Morstein their headliners, and a range of deliciously fun and equally smart natural wines, both ranges just a little more fine-tuned from one year to the next. Sometimes in many things we do, all it takes is one small correction, and BOOM, next level. There’s a third mastery of craft coming into clearer view: Pinot Noir still wine. They’ve been working on it for years, but what we thieved this time from the new collection of old barrels was more solid than ever, and some of it was downright outstanding.

The second leg of this trip with Remy through France and Italy will have to wait until next month—there’s too much to cover, and I’m running out of time for my deadline. But here’s a preview of the jaunt: it was a doozy.

We began early on a Monday morning along Catalonia’s Costa Brava, and from there, it was a marathon in full sprint. But at least on this leg, we were in the comfort of my car, and better equipped: thick and long Yoga mat, foam roller and weights for much-needed exercise, extra winter clothes and jackets (which we needed!), umbrellas, mud boots, running shoes, drone, cameras, and plenty of room for wine (and the unexpected gift of a classic cassoulet clay pot given to me on our first visit!)

First stop: Cahors, followed by a quick hop to Bordeaux. From there, we raced up to Muscadet, crossed the Loire to Chablis, then headed to Les Riceys before a sharp two-hour rollercoaster ride up north to Reims and a faster descent into Jura. We zigged to Côte d’Or, drifted down the Rhône, zagged across the Côte d’Azur into Liguria, took a left at Savona, climbed over the Ligurian range and into Italy’s viticultural promised land for stops in Barolo, Barbaresco, Nizza, and Monferrato Casalese. After that, it was up to Caluso and Alto Piemonte, then we boomeranged to Oltrepò Pavese and back and sped westward toward the coast. From there, we screamed across southern France with a stop in Jurançon, finally wrapping things up back in Navarra, where we parted ways during a firehose-level downpour. Remy was off to London to meet his girlfriend (but even with forty days on the road together, he kept from me that he planned to propose!), and I had an eight-hour drive home to Portugal—eta: midnight. I think I made it there alive, but I’m not sure …