Off-roading through a bumpy, hilly and winding dirt road for what seemed an eternity, we headed into the Itata Valley wilderness, our destination an ancient granite vineyard surrounded by pine and eucalyptus. Along the way we were joined by one of Pedro’s grape growers, Juan Palma. Juan comes from a family with a 300-year-old lineage, centuries of passed down vineyard wisdom. He took the lead in the caravan and we followed closely behind on the dirt road, windows down, eating dirt the entire time. The road was terribly dusty and our car was filled with it. Pedro didn’t seem to mind, though, and I figured this was the norm in hot weather with no AC in the Itata backcountry.

After about thirty minutes we pulled into our first stop. Immediately we were met with warm dry wafts of wind pushing their way through the pine and eucalyptus trees lining the roads. Standing in the vineyards, it’s impossible not to notice the eucalyptus and pine aromas in the air at all times.

Pedro setup an eraser board to illustrate Chile’s geological heritage and how the country was divided up in a simple way: the Andes were volcanic and metamorphic rocks, the Central Valley was filled with alluvial materials from the erosion of the Andes, and the coastal mountains were largely made of granite, an intrusive igneous rock. Years ago, the Chilean government erroneously decided that the old granite hills of the Itata weren’t useful for vineyards. They designated them for growing trees, mostly for making paper products—a controversial ecological dispute in these parts, because of the environmental damage from the pulp mills. Ironically, the native Mapuche Indians continue to light the forests on fire in rebellion to this catastrophe.

Just as we were about to go up to visit one of Pedro’s many soil pits (he’s famous for digging massive holes in vineyards), we had an unexpected visitor. At first glance, I thought she was one of the vineyard owners. Why wouldn’t I think that? We were in a vineyard out in the boonies. But as she got closer, we saw a very small woman with a wind burnt, dark face, sunken in brown eyes, with lines carved into her face from many years of sun exposure. She wore a raggedy, but somewhat classy looking purple overcoat. She walked up to us with her hand extended, mumbling to herself, but really talking to us. She came for money. Pedro quickly went into his car and gave her some Chilean pesos. She made her rounds to the rest of us and Pedro told her that he had given her money for all of us. She smiled and slowly disappeared back into the forest.

Pedro explained that big companies often pay 80 Chilean pesos per kilo of grapes—the equivalent of $.05 per pound.

Like in the U.S., the poor in Chile stay poor, only a lot poorer. Even Chileans who work full time jobs often live in shanty houses made of cardboard and tin siding with dirt floors, even right in the middle of Santiago. In retrospect, it shouldn’t have been such a surprise to see this poor woman out in the middle of nowhere.

In the Itata, big companies from the north have come in to try to dupe the locals out of their land for pennies on the dollar of its potential value. Thankfully, most winegrowers of the Itata haven’t sold their vineyards. Instead, the growers maintain their work and they know that if they did sell, they wouldn’t have any alternatives except to become employees of the company that just bought their land. To them, selling is not an option.

While grapes in high-demand regions of California can go for well over $6000 per ton ($3.00 per pound), Pedro explained that big companies often pay 80 Chilean pesos per kilo of grapes—the equivalent of $.05 per pound. It’s an extraordinarily cheap price to pay for grapes, especially when they come from dry-farmed ancient vineyards with vines that can be older than 200 years. However, more than the ancient vines, the true magic of the Itata are the pink granite soils.

Over 500 years ago, the granite soils of the Itata were one of the first places the Spanish conquistadors planted vines.

If they make the leap, something truly special could happen: they could be making wines authentically Chilean, instead of the big, generic, internationally styled ones.

They got it right back then, and Chile forgot about these vines and the people farming them; at least until producers like DeMartino and Pedro Parra came around. Pedro now pays $.50 per pound for grapes and Juan thought he was stupid to offer to pay him such ridiculous prices. Pedro insisted to Juan that they were worth at least that.

Pedro believes that if the farmers realize what they have, they will be able to flip the balance of power out of the hands of the big wineries. These farmers hold onto their vineyards, despite only making something like $20K each year for their entire family. Yet they know they have no economic future without their vineyards. Pedro believes that if the big companies weren’t able to buy fruit for almost nothing, they would likely start to fail. In fact, it’s thought that some of these old-vine parcels make up significant proportions of their top wines.

One of Pedro’s life dreams is to help the growers in this region make their own commercial wines. His great idea is to gather enough money to take them to other wine regions to see first-hand the story of how extremely poor regions with gifted terroirs (like Piedmont’s Barolo and Barbaresco regions) rose to become frontrunners in the world of wine. If they make the leap, something truly special could happen: they could be making wines authentically Chilean, instead of the big, generic, internationally styled ones.

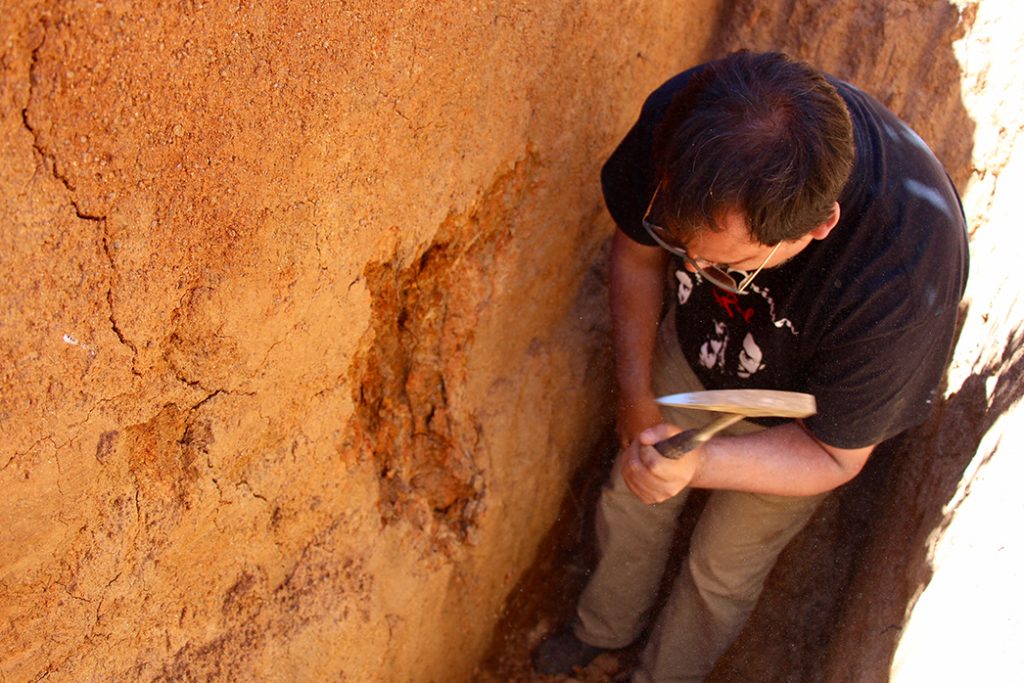

After the lady in purple disappeared back into the forest, Pedro brought us a little way up the hill to view the first of many holes he’d dug in the vineyards. They were about eight feet deep with stairs carved out at the entry. Smiling, Pedro made sure to point out that this hole wasn’t dug just for us, but for the many people that come to the Itata to see the beautiful soils Pedro evangelizes all over the world.

Pedro entered the pit and invited us to come down. With his hammer, he began to pull slabs off the walls that have existed in place for 200 million years. He pointed out the vertical fractures that helped the roots easily find their way down into the many levels of the soil. It’s awe inspiring when you first expose a stone to the sunshine after it’s been buried for millions of years.

Part 4 of 6, “Chicken and Lettuce” will post next week.

To keep up with this story you can sign up to our email list, or check in next week at the same time and you will find part 4.